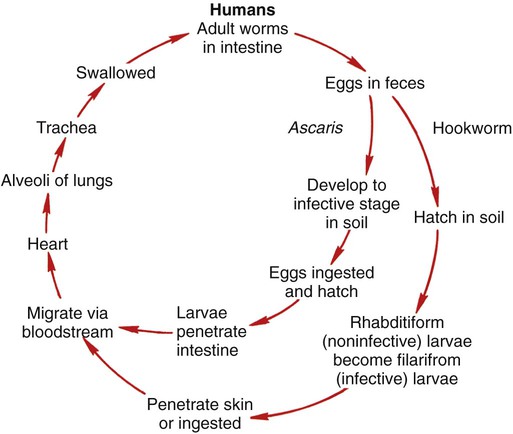

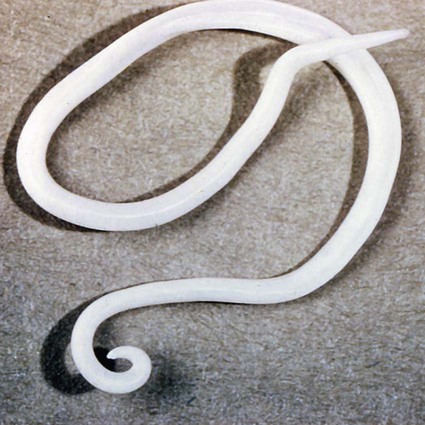

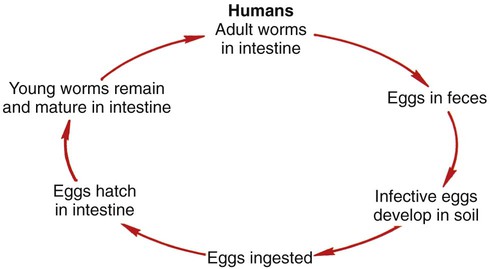

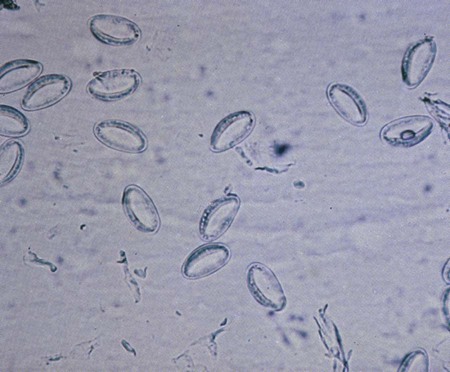

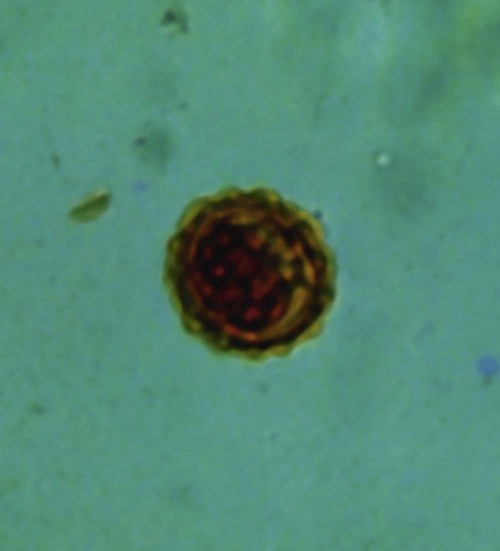

Chapter 51 1. Describe the distinguishing morphologic characteristics and basic life cycle (vectors, hosts, and stages of infectivity) for each of the parasites listed. 2. Define and identify the following parasitic structures when appropriate: mammillated ovum, gravid, rhabditiform larvae, buccal capsule, esophagus, genital primordia, polar hyaline plugs, copulatory bursa, embryonated egg, cutting plates, and filariform larvae. 3. Describe the diseases and mechanism of pathogenicity including route of transmission for each of the species listed. 4. Differentiate Ascaris lumbricoides adult male and female worms. 5. Define and differentiate direct versus indirect life cycle as related to nematodes and the routes of transmission including autoinfection and hyperinfections. 6. Identify and differentiate the characteristic morphologies and eggs for A. lumbricoides, E. vermicularis, and T. trichiura. 7. Compare clinical signs and symptoms, morphologic characteristics, and identification of hookworm’s rhabditiform larvae for Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus. 8. Compare and contrast the morphologic characteristics and identification of the larval forms of Strongyloides stercoralis. 9. List the various methods used to diagnosis intestinal nematode infections. 10. Identify the appropriate intestinal nematodes where the following techniques are useful and explain the principle for each including the Baermann concentration method, agar culture, and Harada-Mori filter paper method for the recovery of intestinal nematodes. Ascaris lumbricoides is the most common and the largest roundworm. The parasite has a worldwide distribution with higher prevalence in the tropical regions. Eggs are ingested and hatch in the duodenum, penetrate the intestinal wall, and migrate to the hepatic portal circulation. The adult worms live and reproduce in the lumen of the small intestine. The ovum is a thick, oval mammillated (outer protrusions) and embryonated egg. The eggs are passed in the feces and become infective 2 to 6 weeks following deposition, depending on the environment. The general life cycle is outlined in Figure 51-1. A. lumbricoides life cycle is classified as an indirect life cycle; transmission is not via a direct route from one host to the next. Many A. lumbricoides infections are asymptomatic. The presentation of symptoms correlates with the length of infection, the number of worms present, and the overall health of the host. Intestinal symptoms range from mild to severe intestinal obstruction. Some patients will develop pulmonary symptoms and present with immune-mediated hypersensitivity pneumonia. The worms may cause an immune condition known as Löffler’s syndrome characterized by peripheral eosinophilia. See Table 51-1 for a summarized detail of associated diseases. TABLE 51-1 Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Associated Diseases Female worms have an extremely high daily output of eggs, making diagnosis relatively easy through the identification of eggs in feces. The large, broadly oval mammillated ova are typically stained brown from bile (Figure 51-2). Some eggs will be decorticated, or lacking the mammillated outer cover. Infertile eggs may be oval or irregular shaped with a thin shell and containing internal granules. Adult worms may also be identified in feces. The male is smaller (15 to 31 cm) with a curved posterior end (Figure 51-3) and contains three well-characterized lips. Larvae may be found in sputum or gastric aspirates as a result of larval migration during development within the human host. Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm) is distributed worldwide and commonly identified in group settings of children ages 5 to 10 years. The life cycle is considered direct; transmission occurs from an infected host to another individual (Figure 51-4). During the night, the mature female worm migrates out of the anus of the infected host and lays eggs in the perianal region. The embryonated eggs will mature and a third-stage larva stage develops, resulting in infectivity within hours. Transmission occurs by ingestion or inhalation of eggs. Reinfection may also occur when the eggs hatch and larvae return to the intestine where they mature. Infections with E. vermicularis are typically asymptomatic. The most common complaint is perianal pruritus (itching) and resultant restless sleep. Occasionally, the parasite may migrate to other nearby tissues, causing pelvic, cervical, or peritoneal granulomas. See Table 51-1 for a summarized detail of associated diseases. Diagnosis is typically by microscopic identification of the characteristic flat-sided ovum (Figure 51-5). The eggs are collected using a sticky paddle or cellophane tape pressed against the perianal region. Eggs are not typically identified in feces, although they may occasionally be found in a stool specimen. Although adult pinworms may be visible, they can be easily confused with small pieces of thread. The female worm measures 8 to 13 mm long with a pointed “pin” shaped tail. In gravid females, almost the entire body will be filled with eggs (Figure 51-6). The males measure only 2 to 5 mm in length, die following fertilization, and may be passed in feces.

Intestinal Nematodes (Roundworms)

Ascaris Lumbricoides

General Characteristics

Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Disease

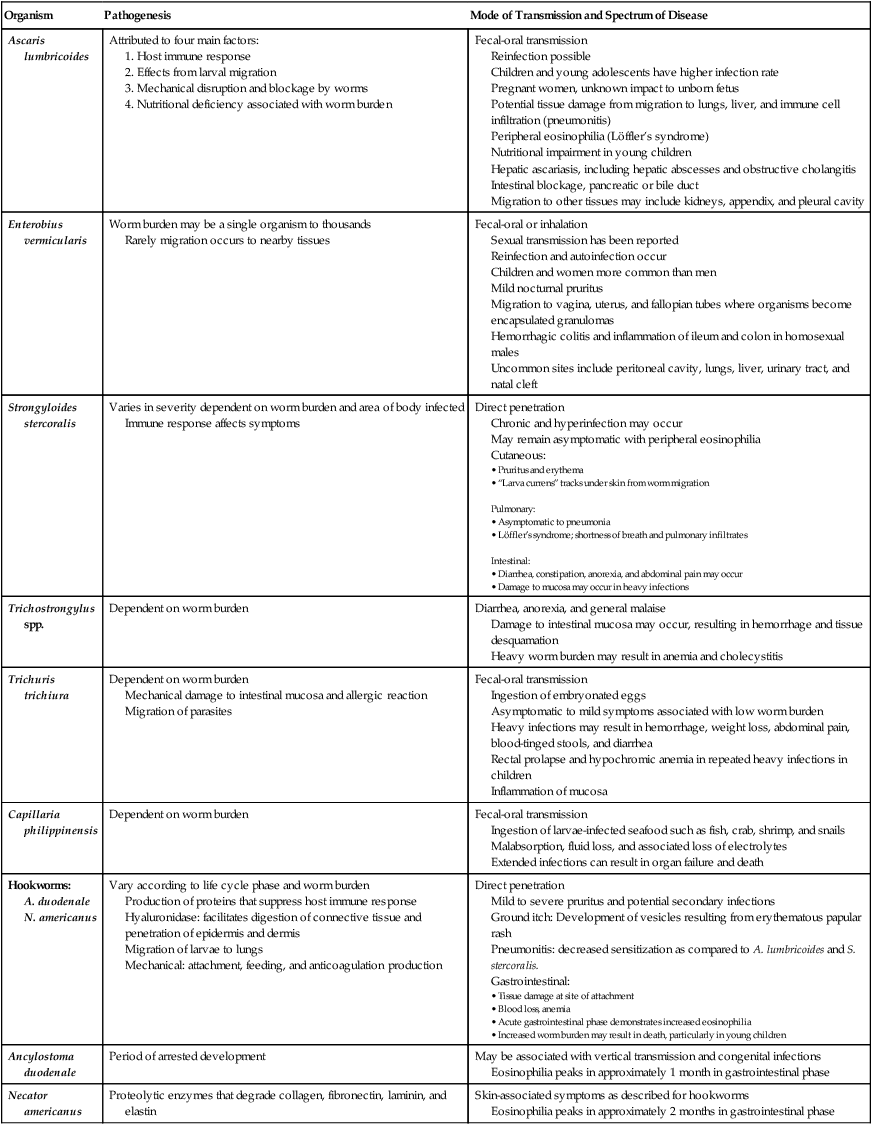

Organism

Pathogenesis

Mode of Transmission and Spectrum of Disease

Ascaris lumbricoides

Attributed to four main factors:

Fecal-oral transmission

Reinfection possible

Children and young adolescents have higher infection rate

Pregnant women, unknown impact to unborn fetus

Potential tissue damage from migration to lungs, liver, and immune cell infiltration (pneumonitis)

Peripheral eosinophilia (Löffler’s syndrome)

Nutritional impairment in young children

Hepatic ascariasis, including hepatic abscesses and obstructive cholangitis

Intestinal blockage, pancreatic or bile duct

Migration to other tissues may include kidneys, appendix, and pleural cavity

Enterobius vermicularis

Worm burden may be a single organism to thousands

Rarely migration occurs to nearby tissues

Fecal-oral or inhalation

Sexual transmission has been reported

Reinfection and autoinfection occur

Children and women more common than men

Mild nocturnal pruritus

Migration to vagina, uterus, and fallopian tubes where organisms become encapsulated granulomas

Hemorrhagic colitis and inflammation of ileum and colon in homosexual males

Uncommon sites include peritoneal cavity, lungs, liver, urinary tract, and natal cleft

Strongyloides stercoralis

Varies in severity dependent on worm burden and area of body infected

Immune response affects symptoms

Direct penetration

Chronic and hyperinfection may occur

May remain asymptomatic with peripheral eosinophilia

Cutaneous:

Pulmonary:

Intestinal:

Trichostrongylus spp.

Dependent on worm burden

Diarrhea, anorexia, and general malaise

Damage to intestinal mucosa may occur, resulting in hemorrhage and tissue desquamation

Heavy worm burden may result in anemia and cholecystitis

Trichuris trichiura

Dependent on worm burden

Mechanical damage to intestinal mucosa and allergic reaction

Migration of parasites

Fecal-oral transmission

Ingestion of embryonated eggs

Asymptomatic to mild symptoms associated with low worm burden

Heavy infections may result in hemorrhage, weight loss, abdominal pain, blood-tinged stools, and diarrhea

Rectal prolapse and hypochromic anemia in repeated heavy infections in children

Inflammation of mucosa

Capillaria philippinensis

Dependent on worm burden

Fecal-oral transmission

Ingestion of larvae-infected seafood such as fish, crab, shrimp, and snails

Malabsorption, fluid loss, and associated loss of electrolytes

Extended infections can result in organ failure and death

Hookworms:

A. duodenale

N. americanus

Vary according to life cycle phase and worm burden

Production of proteins that suppress host immune response

Hyaluronidase: facilitates digestion of connective tissue and penetration of epidermis and dermis

Migration of larvae to lungs

Mechanical: attachment, feeding, and anticoagulation production

Direct penetration

Mild to severe pruritus and potential secondary infections

Ground itch: Development of vesicles resulting from erythematous papular rash

Pneumonitis: decreased sensitization as compared to A. lumbricoides and S. stercoralis.

Gastrointestinal:

Ancylostoma duodenale

Period of arrested development

May be associated with vertical transmission and congenital infections

Eosinophilia peaks in approximately 1 month in gastrointestinal phase

Necator americanus

Proteolytic enzymes that degrade collagen, fibronectin, laminin, and elastin

Skin-associated symptoms as described for hookworms

Eosinophilia peaks in approximately 2 months in gastrointestinal phase

Laboratory Diagnosis

Enterobius Vermicularis

General Characteristics

Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Disease

Laboratory Diagnosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Intestinal Nematodes (Roundworms)