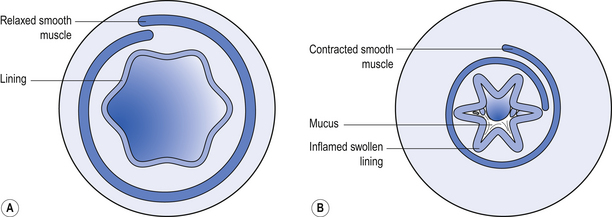

43 Inhaled products are specialized dosage forms, which are designed to deliver medicines directly to the lung. A variety of inhaler devices are in use, all of which require the user of the inhaler to adopt an appropriate inhaler technique. Failure to use the correct inhaler technique will result in treatment failure. The pharmacist, who is usually the person who gives (dispenses) the inhaler to the patient, is ideally placed to demonstrate the appropriate inhalation technique for that inhaler. Using an inhaler is a skill, subject to the development of ‘bad habits’, which can lead to poor technique. Inhaler technique should therefore be regularly checked to ensure that the technique is optimal; again the pharmacist is ideally placed to perform this function. There are significant differences in the way that inhalers are prescribed for asthma and COPD. In COPD, the emphasis of treatment is on the use of bronchodilators, and it may be appropriate for a COPD patient to have a long-acting inhaled beta-agonist without an inhaled steroid. This is different from asthma treatment where a long-acting beta-agonist should always be prescribed with an inhaled steroid. The scope of this chapter is limited to commonly used inhaled treatments and devices used for these inhaled treatments. By being familiar with national treatment guidelines for asthma and COPD, pharmacists can be assured that the advice that they give patients is likely to be consistent with that given by other healthcare professionals. These guidelines are: BTS/SIGN Asthma Guideline, 2011 (January 2012 revision): http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/guidelines/asthma-guidelines.aspx and NICE CG101 Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101/NICEGuidance/pdf/English. Using the inhaled route when the lung is the target organ has a number of advantages: The specific target in the lung for medicines used in asthma and COPD is the bronchiole. Branching from bronchi, bronchioles are the first airways in the lung not to contain cartilage and are less than 1 mm in diameter. The absence of cartilage means that smooth muscle contraction reduces the size of the airway. Inflammation also results in reduction in size of the airway (Fig. 43.1). Salbutamol and terbutaline are widely used SABAs. They act on beta2 receptors in the smooth muscle of bronchioles to reverse bronchospasm. Symptoms caused by bronchospasm include wheeze, coughing, breathlessness and a feeling of tightness of the chest. For this reason, SABAs are often referred to as ‘relievers’ and should be used ‘as required’ to relieve symptoms. If a reliever inhaler is required for asthma more than twice a week most weeks, the addition of a ‘preventer’ (usually a steroid) inhaler should be considered. Unwanted effects of inhaled beta2 agonists are rare but tremor can occur.

Inhaled route

The rationale for using the inhaled route

The rationale for using the inhaled route

The appropriate use of the most widely prescribed inhaled medicines

The appropriate use of the most widely prescribed inhaled medicines

The role of the peak flow meter

The role of the peak flow meter

The different types of inhaler, and inhaler technique

The different types of inhaler, and inhaler technique

The role of the pharmacist

Introduction

The inhaled route

The antibiotic colistimethate sodium is nebulized to treat lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis

The antibiotic colistimethate sodium is nebulized to treat lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis

The antiviral zanamivir is presented as a dry-powder inhaler for treating influenza.

The antiviral zanamivir is presented as a dry-powder inhaler for treating influenza.

A smaller dose can be used. The normal adult oral dose of salbutamol is 4 mg, but the normal inhaled dose of salbutamol is 200 μg

A smaller dose can be used. The normal adult oral dose of salbutamol is 4 mg, but the normal inhaled dose of salbutamol is 200 μg

The risk of unwanted systemic effects is reduced

The risk of unwanted systemic effects is reduced

A faster onset of action may be achieved with some drugs, e.g. salbutamol

A faster onset of action may be achieved with some drugs, e.g. salbutamol

Topically active drugs with poor oral bioavailability can be used.

Topically active drugs with poor oral bioavailability can be used.

Inhaled medicines used for asthma and COPD

Short-acting beta2 agonists (SABAs)

Points to note

The inhaler itself is not dangerous – but asthma is potentially life-threatening

The inhaler itself is not dangerous – but asthma is potentially life-threatening

Appropriate, ‘as required’ use of a reliever inhaler provides a useful marker of the severity of the condition

Appropriate, ‘as required’ use of a reliever inhaler provides a useful marker of the severity of the condition

Frequent usage of a reliever inhaler may indicate severe uncontrolled asthma

Frequent usage of a reliever inhaler may indicate severe uncontrolled asthma

There is no risk that using the reliever inhaler whenever needed will result in a diminishing response, but worsening asthma will not respond to a reliever inhaler alone – additional treatment is required

There is no risk that using the reliever inhaler whenever needed will result in a diminishing response, but worsening asthma will not respond to a reliever inhaler alone – additional treatment is required

If the reliever inhaler is not relieving symptoms, urgent medical attention is required

If the reliever inhaler is not relieving symptoms, urgent medical attention is required

If reliever inhaler usage has increased, or is being used more than twice a week most weeks, review of treatment is required

If reliever inhaler usage has increased, or is being used more than twice a week most weeks, review of treatment is required

The reliever inhaler can be used immediately before sport/exercise to prevent exercise-induced asthma in susceptible individuals

The reliever inhaler can be used immediately before sport/exercise to prevent exercise-induced asthma in susceptible individuals

Long-acting beta2 agonists (LABAs)

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)

Poor absorption from the gastrointestinal tract to minimize systemic effects due to the swallowed portion

Poor absorption from the gastrointestinal tract to minimize systemic effects due to the swallowed portion

Complete metabolism in the ‘first pass’ through the liver

Complete metabolism in the ‘first pass’ through the liver

Metabolism in the lung to inactive metabolites (absorption from the lung circumvents the ‘first pass’ through the liver).

Metabolism in the lung to inactive metabolites (absorption from the lung circumvents the ‘first pass’ through the liver).![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Inhaled route

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue