30

Heart

The heart is a specialized pump that propels blood to the body. It lies between the lungs in the mediastinum, which is subdivided into the superior and inferior mediastinum by an imaginary horizontal line drawn from the sternal angle to the inferior border of vertebra TIV. The inferior mediastinum is further subdivided into the anterior, middle, and posterior mediastinum.

Support for the heart comes from surrounding structures:

- ribs, costal cartilages, and sternum anteriorly

- vertebral bodies of the middle thoracic vertebrae posteriorly

- central tendon of the diaphragm inferiorly

- connection of the heart to the great vessels—the aorta, pulmonary trunk, and superior vena cava—superiorly

- vertebral bodies of the middle thoracic vertebrae posteriorly

Embryologically, the heart develops as a midline structure, but in adults it is oriented obliquely and shifted to the left side of the chest. It is a cone-shaped muscular pump with its apex inferior, at the fifth intercostal space in the midclavicular line, and its base superior, near its junction with the great vessels.

The four chambers of the heart have a multilayered lining—the endocardium, the myocardium (or middle muscular layer), and the epicardium (a superficial layer that includes the visceral layer of the pericardium).

The pericardium (pericardial sac) is a strong double-layered sac around the heart and roots of the great vessels. It has a thick, tough outer part (the fibrous pericardium) and an inner serous pericardium. The serous pericardium has two layers (the parietal and visceral layers), which form a potential space—the pericardial cavity. This cavity is filled with a thin film of serous fluid to reduce friction as the heart pumps and moves within the sac. The pericardium is innervated by branches of the vagus nerve [X], sympathetic nerve fibers that follow the route of the blood vessels, and the phrenic nerves.

Chambers of the Heart

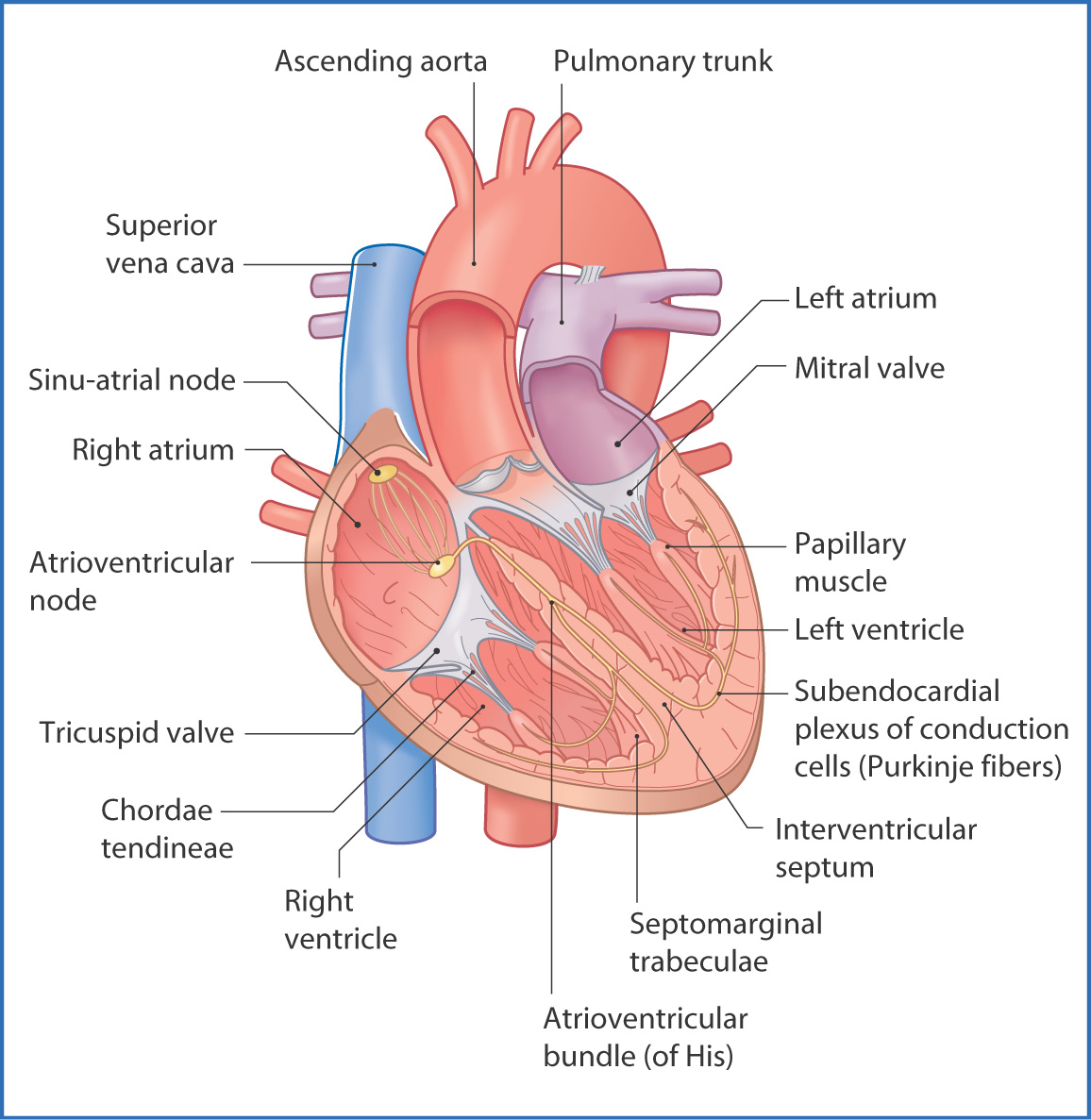

The heart has four chambers—the right atrium, right ventricle, left atrium, and left ventricle (Fig. 30.1). The right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from the body. It pumps this blood to the right ventricle, which then pumps it to the lungs; this is the pulmonary circulation. The left atrium receives oxygenated blood from the lungs. It pumps it to the left ventricle, which then pumps it to the body; this is the systemic circulation. The atria operate under relatively low pressure and therefore have thinner walls than the ventricles, which operate at much higher pressure.

FIGURE 30.1 The four chambers of the heart and the cardiac conduction system.

RIGHT ATRIUM

Deoxygenated blood from the head, neck, and upper limbs drains into the right atrium through the superior vena cava; blood draining from the abdomen, pelvis, and lower limbs flows into the right atrium through the inferior vena cava during ventricular rest (diastole).

The right atrium forms the right border of the heart. Its walls are thin and contain an internal muscular ridge (the crista terminalis), which is oriented vertically between the superior and inferior venae cavae. Externally, this ridge is visible as a shallow groove (the sulcus terminalis cordis). The internal surface of the right atrium also has many small ridges known as pectinate muscles (musculi pectinati). Within the right atrium there is a shallow depression (the fossa ovalis) on the interatrial septum that marks the site of the fetal foramen ovale.

RIGHT VENTRICLE

Blood leaving the right atrium passes through the tricuspid valve (right atrioventricular valve) into the right ventricle, which is the most anterior chamber of the heart. The tricuspid valve consists of three cusps (or leaflets) held in place by chordae tendineae, which are slender fibrous threads that connect the valve cusps to the papillary muscles. The papillary muscles originate from the internal wall of the right ventricle. The valve cusps, chordae tendineae, and papillary muscles prevent the valve from “blowing out” or leaking under the high pressure created during ventricular contraction.

The internal surface of the right ventricle is roughened by many muscular ridges and projections (the trabeculae carneae). One of these muscular ridges, the septomarginal trabecula (moderator band), carries the right branch of the atrioventricular bundle, which is part of the conduction system of the heart. Another muscular ridge—the supraventricular crest—separates the inflow (venous) and outflow (conus arteriosus or infundibulum) tracts of the right ventricle.

The right ventricle contracts under moderate pressure during ventricular systole. As it does, the tricuspid valve closes and the pulmonary valve opens. Blood flows through the pulmonary valve, which has three cusps, and passes through the pulmonary arteries to the lungs. The simultaneous closing of the mitral and tricuspid valves and the opening of the pulmonary valve create the first heart sound heard over the precordium (anterior chest wall) when examining a patient with a stethoscope.

LEFT ATRIUM

Blood that has been oxygenated in the lungs returns to the left atrium through the pulmonary veins. The left atrium, which forms most of the base of the heart, is posterior to the right atrium. The esophagus, left pulmonary bronchus, and descending aorta are posterior to the left atrium. The four valveless pulmonary veins enter the left atrium on its posterior wall.

Internally, the left atrium, like the right atrium, contains pectinate muscles. On the interatrial septum there is a fossa ovalis corresponding to that of the right atrium. Blood flows through the mitral valve

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree