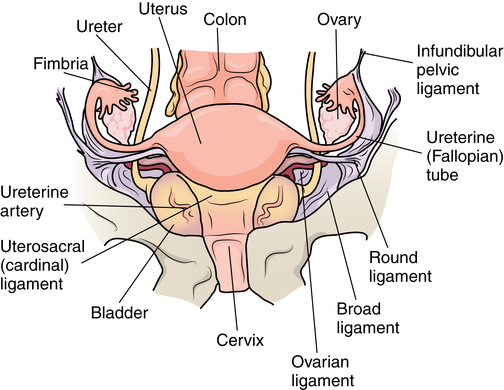

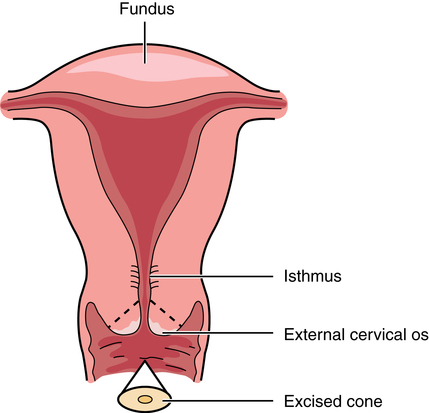

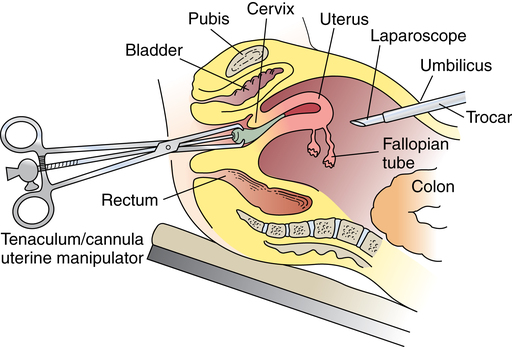

Chapter 34 After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to: • Identify the organs of the female genitourinary system. • Describe the physiology of the female reproductive system. • Differentiate between adolescent and adult gynecologic health. • Describe the pertinent considerations when caring for a pregnant patient. Termination of pregnancy. Several descriptions are as follows: Elective voluntary surgical ending of pregnancy First trimester: pregnancy is terminated during first 3 months of gestation; Second trimester: pregnancy is terminated during second 3 months of gestation; Late: pregnancy is terminated after the second trimester has ended. Incomplete natural termination of pregnancy before the age of viability Products of conception are partially retained and may need surgical removal to prevent sepsis in the mother. Natural termination of gestation before the age of viability. Products of conception must be surgically removed to prevent sepsis in the mother. Natural termination of pregnancy before age of viability. Products of conception are expelled without surgical intervention. Pregnancy is diagnosed at risk for natural termination before the age of viability. Medical and/or surgical management may be attempted to prevent full natural termination. Absence of menstrual periods. Surgical delivery of a fetus through an abdominal incision. Also known as cesarean section or C-section. Instillation of dye through the fallopian tubes as a test of patency. Progressive enlargement of the opening of the uterine cervix is to permit instrumentation for debulking the endometrium and other surgical procedures. Lining of the uterus that is normally shed during menstruation. The round top or dome of uterus. Term for fibroid tumors. Also known as myoma (e.g., uterine muscle tumor). Mature ovum. Pregnant. Beginning of menstruation. Bleeding between menstrual periods in a premenopausal woman that is surgically treated by dilation and curettage, endometrial ablation, or hysterectomy. Excessive bleeding at menstruation that is surgically treated by dilation and curettage, endometrial ablation, or hysterectomy. The shedding of the endometrium during periodic hormonal cycles. New tissue overgrowth. Potentially cancerous. Products of conception retained either at delivery of a viable fetus or at the time of incomplete abortion. Placental remnants. Incremental measurement of sexual development from first signs of puberty to maturity in both sexes. The beginning of breast development that is measured in stages. The female genitourinary system comprises the organs, glands, secretions, and other elements of reproduction referred to as the pudendum. Components of the female reproductive system are both external and internal organs. The term vulva is used collectively for the female external genitalia (Fig. 34-1). This sensitive, delicate area is highly vascular, with an extensive superficial and deep lymph supply and rich cutaneous sensory innervation. It includes the following: The internal female reproductive organs (Fig. 34-2) lie within the pelvic cavity, protected by the bony pelvis. Bones and ligaments form the pelvic outlet. The dilated cervix of the uterus and the vagina constitute the birth canal. The vault (upper part of the vagina) is divided into four fornices, or arches (Fig. 34-3). During digital pelvic examination, pelvic organs can be palpated through the thin walls of the vault. The anterior fornix, in front of the cervix, is adjacent to the base of the bladder and distal ends of the ureters. The following apply to both vaginal and abdominopelvic procedures: 1. Spinal, epidural, or (more commonly) general anesthesia is used. An epidural catheter may be inserted preoperatively for postoperative pain control. 2. A Foley catheter may be inserted after the administration of the anesthetic agent to prevent the bladder from becoming distended during the procedure and to record urinary output. The circulating nurse and the anesthesia provider should check the urinary drainage bag frequently and report urine volume or evidence of blood. This could indicate injury to the bladder or ureters. Percutaneous insertion of a cannula directly into the bladder through the abdominal wall (suprapubic cystostomy) provides an alternative indwelling urinary drainage system in select patients. 3. An electrosurgical unit (ESU), with either monopolar or bipolar electrodes, is frequently employed. 4. Argon, CO2, and neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) lasers are used, generally in conjunction with a colposcope or laparoscope and the operating microscope for some procedures. 5. Closed-wound suction drainage, or another type of drain, may be used to prevent hematoma or serum accumulation in the pelvis and/or the wound. 6. Prophylactic preoperative anticoagulation with subcutaneous heparin, antiembolic stockings, sequential compression devices, and early ambulation are especially important in pelvic surgery because of the potential for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and subsequent pulmonary emboli (PE). 1. The patient is in the lithotomy position. 2. Instrumentation must be of sufficient length for use within the vaginal canal and uterine cavity. In addition to retracting, cutting, holding, clamping, and suturing instruments, vaginal setups include dilation and curettage (D&C) instruments for intrauterine procedures (Table 34-1). TABLE 34-1 Instruments for Dilation and Curettage 3. A laser, ESU, or cryosurgical unit may be used to remove hypertrophied tissue or certain benign neoplasms. 4. A suction system, including a Poole suction tip with guard, tubing, and collection canister, is part of the setup. 5. Raytec sponges are rolled and secured on sponge forceps in deep areas (also referred to as sponge sticks). Long, narrow, 4 × 18-inch sponges with radiopaque markers on the end are used for packing off abdominal viscera in vaginal procedures. All counts are very important in these procedures. 6. Vaginal packing is inserted after certain procedures for hemostasis and/or therapeutic purposes. Antibiotic or hormone cream may be applied to the packing during insertion. Impregnated vaginal packing is commercially available. The packing should be recorded on the patient’s chart and removed at the surgeon’s order. 7. At the completion of the surgical procedure, a sanitary pad is placed against the perineum between the patient’s legs. 1. The supine or Trendelenburg’s position is used for abdominopelvic procedures to displace pelvic organs cephalad. Preparation and drapes are the same as for abdominal laparotomy. Abdominal incisions commonly used in gynecologic open procedures are shown in Figure 34-4. 2. When a large abdominal mass is present or the pelvic organs are pushed from their normal relationships, ureteral catheters may be inserted via cystoscopy before the surgical procedure to facilitate identification of the ureters to prevent inadvertent dissection. Severing of the ureters during the procedure greatly increases postoperative morbidity and mortality if the injury is not immediately detected and corrected. 3. Instrumentation includes the basic laparotomy setup with the addition of long instruments for deep manipulations within the pelvis and uterine graspers, such as a Somer uterine elevator or a tenaculum. The following considerations apply: 1. Because of the possibility of infection, separate sterile setups are used for vaginal and abdominal procedures performed concurrently. 2. Vaginal preparation precedes exploratory pelvic laparotomy in readiness for the unexpected or for a D&C scheduled to precede an abdominal procedure. A separate sterile prep table is used for the external genitalia and vagina. Another sterile setup is used for the abdominal preparation. The vaginal area is prepped first to prevent splashing up to a freshly prepped abdomen. Patients diagnosed by Pap smear as having severe cervical dysplasia or intraepithelial carcinoma of the cervix require conization to remove the lesion and rule out invasive carcinoma. The biopsy, obtained with a laser, scalpel, or cervitome (cold knife conization), includes the squamocolumnar junctions of the ectocervix (transformation zone) and is tapered to include the endocervical canal to the level of the internal os (Fig. 34-5). Most of the lesions categorized as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), dysplasia, or carcinoma in situ are found in this area. Conization of the cervix provides the most comprehensive specimen to diagnose a premalignant or malignant lesion. Multiple blocks and sections are examined by the pathologist to determine the extent of invasive disease. X-ray study of the uterus and tubes may afford further evaluation of infertility after repeated negative Rubin test findings. The patient is placed in the lithotomy position, and the vagina is prepped. The cervix is grasped with a single-tooth tenaculum. A cannula is inserted into the cervical canal, and 10 mL of a water-soluble radiopaque contrast medium is instilled with a syringe through the cannula (Fig. 34-6). This contrast medium ascends into the corpus uteri and fallopian tubes to yield information about structure and function. Serial x-rays may be taken to assess postprocedure tubal spillage. In some patients, tubal spasms prevent immediate passage of the contrast medium through the tubes. Procedures using a 10- or 12-mm fiberoptic laparoscope with a 0- or 30-degree-angle lens inserted into the peritoneal cavity permit direct observation of pelvic and abdominal organs and peritoneal surfaces. Single-port or multiple-port laparoscopic methods can be used.20 Endoscopic techniques may be used to diagnose and treat ectopic pregnancy; inspect the ovaries for evidence of follicular activity and retrieve ova for in vitro fertilization; visualize and reduce pelvic masses; and determine the cause of infertility, endocrinopathies, or amenorrhea. Many pelvic diseases, such as endometriosis, adhesions, and ovarian cysts, may be identified and treated through the laparoscope and its accessory instrumentation. The gynecologist can perform myomectomy, salpingectomy, oophorectomy, hysterectomy,20 and other procedures such as tuboplasty and incidental appendectomy without the need for a large abdominal incision. Surgical procedures such as tubal sterilization by electrocoagulation with or without partial resection, placement of a clip or silicone ring on the tube, or biopsy can be performed. Usually a general anesthetic agent is administered. The patient is placed in a modified lithotomy position with the stirrups adjusted so that the legs are at 45-degree angles to the axis of the operating bed. Improper positioning can result in lower leg neuropathy.5 A tenaculum is placed on the cervix. A cannula is inserted into the uterine cervix for instillation of dye and for manipulation of the uterus during the procedure to provide greater visibility (Fig. 34-7). A D&C may be performed as part of the procedure after the injection of dye or contrast media. Additional secondary trocars and sheaths can be placed in the suprapubic hairline (see Fig. 34-12, later). These trocars may be inserted into the peritoneal cavity under direct vision through the endoscope, which offers good transillumination for the puncture when the room lights are dimmed, or visualization on the video monitor. A secondary trocar should have a gas port to which the CO2 tubing can be attached to prevent the cold gas from causing the scope to fog. The suction-irrigation tubing is attached to a side port on the secondary sheath. Benign growths on the vulva, although rare, consist mainly of fatty and fibrous tumors. These are excised if large. Suspicious lesions should be removed for pathologic examination.17 Cancerous lesions may be multicentric, with the majority found on the labia majora and a lesser percentage on the labia minora, vestibule, clitoris, and posterior commissure. Vaginal smears should be taken to determine the presence of metastatic growth to the vaginal wall. Treatment depends on the size of the primary lesion, involvement of nodes, and extent of metastasis. Mutilative procedures require emotional adjustment to permanent change. Wide local excision of a single well-localized area with no premalignant changes elsewhere may be done. Punch biopsies may be obtained. Leukoplakia and preinvasive lesions of the vulva may be treated with a laser or ultrasonic aspirator.17

Gynecologic and obstetric surgery

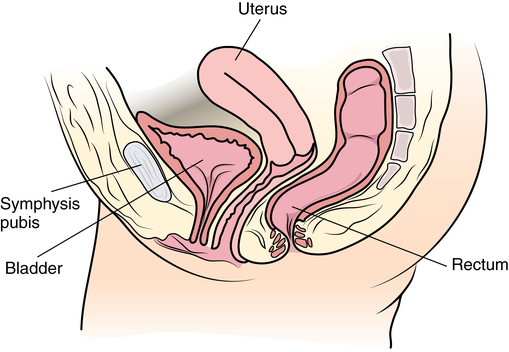

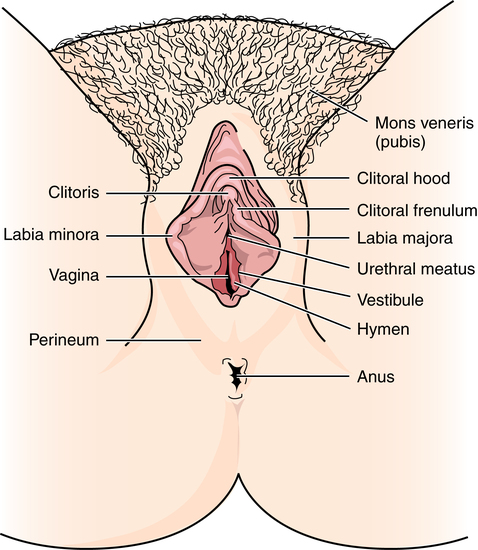

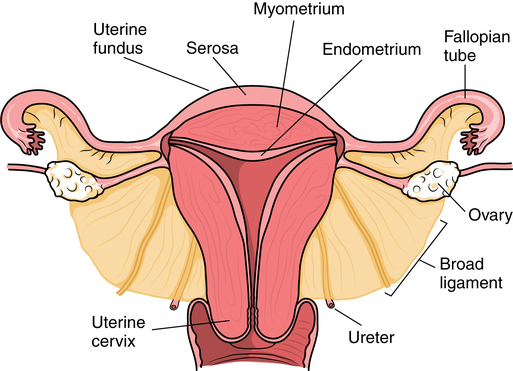

Anatomy and physiology of the female reproductive system

External female genitalia

Internal female reproductive organs

Vagina

Gynecology: general considerations

Special features of gynecologic surgery

Vaginal approach

Purpose

Instruments

To expose

Vaginal speculum

Posterior retractor

Weighted posterior retractor

Narrow lateral Heaney retractors

To grasp and hold

Single- and double-toothed tenacula

To measure uterine cavity

Uterine sound (graduated probe)

To dilate cervix

Graduated dilators

Goodell dilator

To scrape tissue

Sharp and blunt, large and small uterine curettes

To obtain specimen

Endometrial biopsy suction curette

To carry sponges

Sponge forceps

To remove polyps and biopsy tissue

Polyp and biopsy forceps

To insert packing

Uterine dressing forceps

Abdominal approach

Combined vaginal-abdominal approach

Diagnostic techniques

Biopsy of the cervix

Cone biopsy

Fallopian tube diagnostic procedures

Tubal perfusion

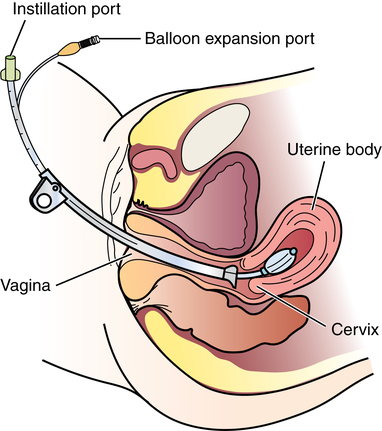

Hysterosalpingography

Pelvic endoscopy

Laparoscopy

Vulvar procedures

Diseases of the vulva

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Gynecologic and obstetric surgery

Website

Website