6. Genital System Introduction Function and terms: The genital organs, which in humans are sex-specific, are responsible for producing offspring. In mammals, including humans, the primary function of the reproduction system in males and females is to produce haploid cells (gametes) in specialized organs (the gonadae), which then fuse in the female organism to form a diploid zygote. During sexual intercourse, male gametes are propelled out of the male’s reproductive tract and into the female reproductive tract where they fuse with the female gametes (conception). The initially singlecelled organism, the zygote, is transported to the uterus where further embryonic development takes place. At the end of pregnancy (gestation), the baby is delivered through the birth canal. In mammals, the male is only involved in conception, whereas the female reproductive system helps create optimal conditions for the fetus to grow and to ensure a timely delivery. In both sexes, gender-specific hormones (sex hormones), which are produced in the gonadae, control these functions. These hormones determine the development and function of both the reproductive organs and the secondary sex characteristics of the individual organism. Classification: The organization of the male and female reproductive systems can be classified in various ways: • Topographically (see A): the internal genital organs (within the body cavity) and the external genital organs (outside of the body cavity). • Functionally (B and C): as organs responsible for producing gametes and hormones (the gonadae), as organs involved in transport (of gametes), as organs involved with incubation and copulation, and as glands associated with the organs. • Ontogenetically (see p. 4). Functional differences between male and female genital systems: Both sexes produce gametes, which in males are referred to as spermatozoa and in females as oocytes. While spermatozoa are continuously produced from primordial germ cells (spermatogonia) from puberty until old age (several dozen millions per day), the number of oocytes is already determined at birth (they can only differentiate into fertilizable germ cells—one egg ripens each menstrual cycle). The production of spermatozoa, and thus offspring, in males is possible from puberty until old age. In females the ability to reproduce is limited to a period ranging from the differentiation of the first ovum in the woman’s first menstrual cycle (menarche, onset around ages 13–14) to the differentiation of the last ovum (menopause, onset varies considerably, approx. between ages 40–60). It is important to keep in mind that mature eggs released in one of the first or last menstrual cycles may be less fertilizable. A Male and female internal and external genitalia*

6.1 Overview of the Genital System

| Male | Female |

Internal genitalia | Testis Epididymis Ductus deferens Prostata Gl. vesiculosa Gl. bulbourethralis | Ovarium Uterus Tuba uterina Vagina (upper portion) |

External genitalia | Penis and urethra Scrotum and coverings of the testis | Vestibulum vaginae Labia majora and minora Mons pubis Gll. vestibulares majores and minores Clitoris |

* The female external genitalia (pudendum femininum) are known clinically as the vulva. | ||

B Functions of the male genital organs

Organ | Function |

Testis | Germ-cell production Hormone production |

Epididymis | Reservoir for sperm (sperm maturation) |

Ductus deferens | Transport organ for sperm |

Urethra | Transport organ for sperm and urinary organ |

Accessory sex glands (prostata, vesiculae seminales, and gll. bulbourethrales) | Production of secretions (semen) |

Penis | Copulatory and urinary organ |

C Functions of the female genital organs

Organ | Function |

Ovaria | Germ-cell production Hormone production |

Tuba uterina | Site of conception and transport organ for zygote |

Uterus | Organ of incubation and parturition |

Vagina | Organ of copulation and parturition |

Labia majora and minora | Copulatory organ |

Gll. vestibulares majores and minores | Production of secretions |

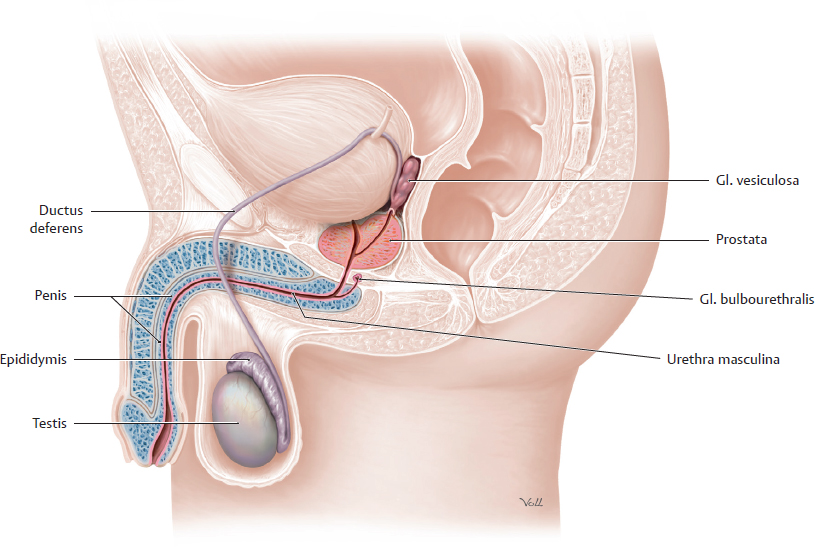

D Overview of the male genital organs

Schematic representation of the male genital organs, viewed from the left side.

Note: The urethra masculina is part of both the male urinary system and the male reproductive system. The male gonadae, the testes, lie outside the body cavity in a pouch of skin called the scrotum.

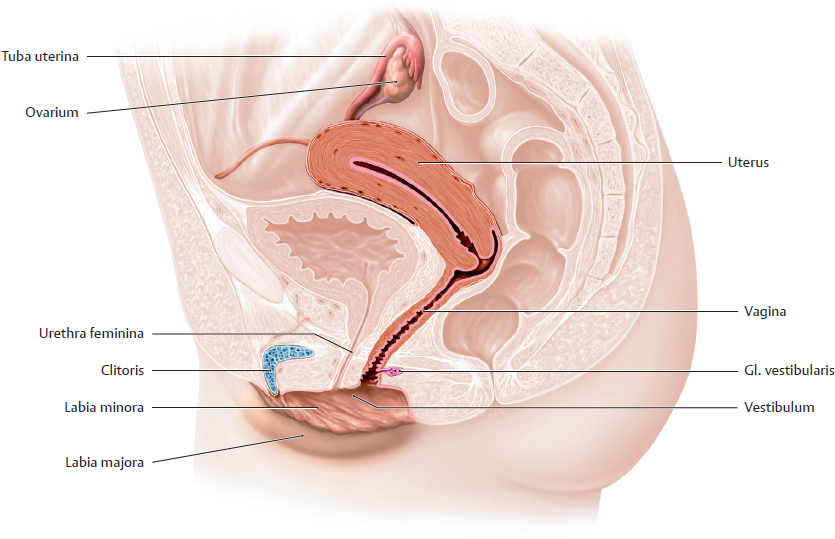

E Overview of the female genital organs

Schematic representation of the female genital organs, viewed from the left side.

Note: The urethra feminina opens into the vestibulum vaginae. However, unlike in males, the urethra feminina is not part of the female reproductive system. The female gonadae, the ovaria, are located in the cavity of the pelvis minor.

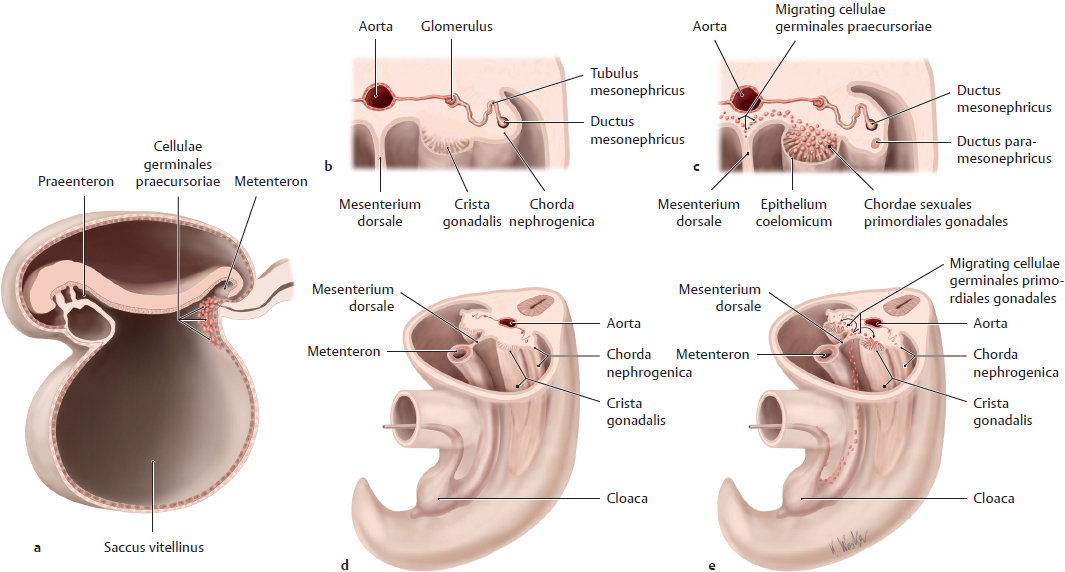

6.2 Development of the Gonadae

Ontogeny-based classification of the genital organs

Embryological structures involved in the formation of male and female genital organs:

• Derivatives of the gonadal primordia: They give rise to the gonads and develop from epithelium coelomicum and mesoderma in the crista gonadalis (see A–C).

• Derivatives of the ductus mesonephrici and paramesonephrici (see p. 50). They give rise to major parts of the genital tracts:

– in males the ductus mesonephricus gives rise to the ductus deferens;

– in females the ducti paramesonephrici gives rise to the tubae uterinae, uterus and part of the vagina

• Derivatives of the perineal region: The tubercula genitalia, plicae cloacales, and tubercula labioscrotalia give rise to the external genitalia (see p. 55).

• Derivatives of the sinus urogenitalis adjacent to the perineal region:

– in both sexes the sinus urogenitalis gives rise to the urethra. In males the urethra and the associated prostata are also part of the genital system;

– in females the sinus urogenitalis gives rise to part of the vagina.

Note: In males and females, the development of both the gonadae and the duct system initially pass through an indifferent stage (stadium neutrale) in which gender is not morphologically distinguishable. Over subsequent stages, only one gender-specific duct system fully develops in each sex, while the other regresses. In some people, nonfunctioning remnants of the regressed duct system can become clinically significant (e.g., Gärtner’s duct cyst, see p. 54).