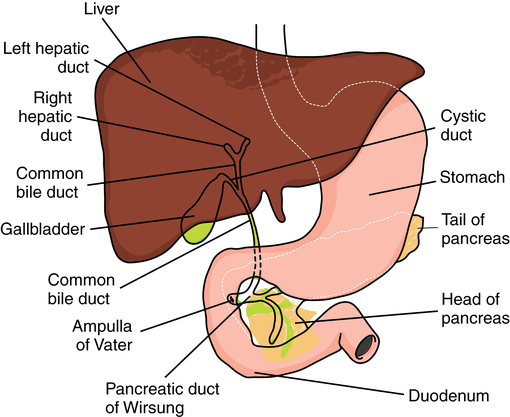

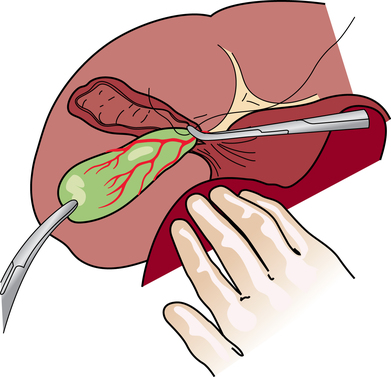

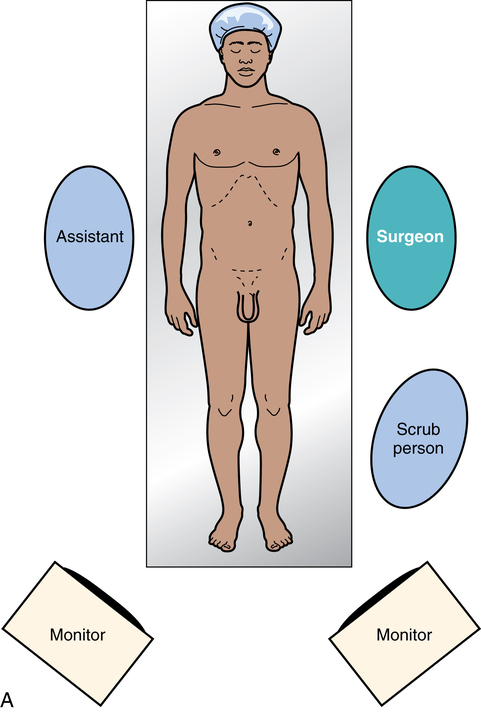

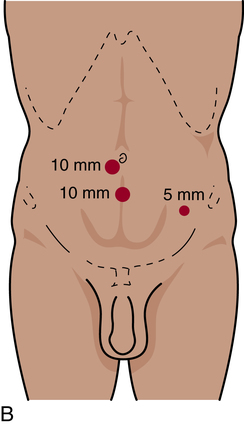

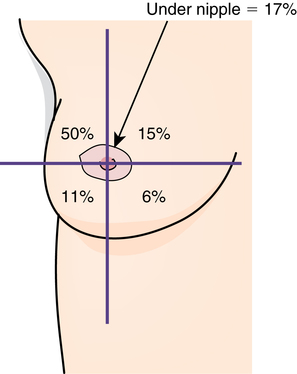

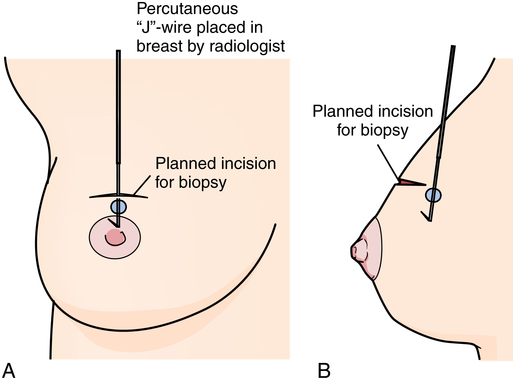

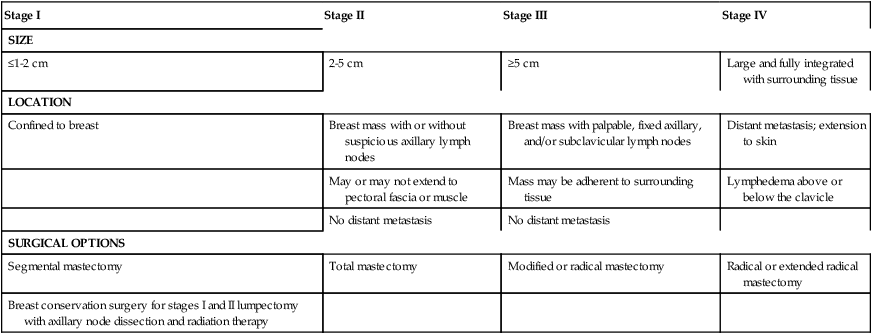

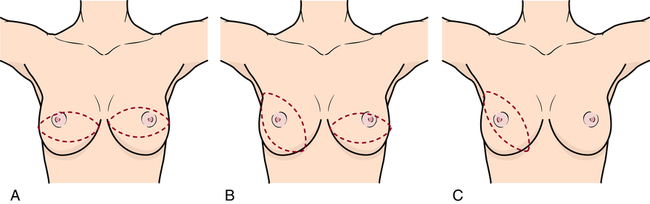

Chapter 33 After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to: • Describe the pertinent surgical anatomy of the breast. • Describe the surgical procedures used to diagnose breast cancer. • Identify the pertinent anatomy of the abdominal organs within the peritoneal cavity. • Discuss the differences between laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. • List the types of anastomoses used for intestinal surgery. • List several surgical diagnostic procedures used to evaluate abdominal trauma. • Differentiate between direct and indirect inguinal hernia. • Discuss the psychological effects of limb amputation on the patient under regional anesthesia. The discipline of general surgery provides the fundamentals for surgical practice, education, and research. The definition of general surgery agreed on by the American Board of Surgery and the Residency Review Committee for Surgery serves as the basis of graduate education and certification as a specialist in surgery. The following principles are inherent in general surgery: • A central core of knowledge and skills common to all surgical specialties (e.g., anatomy, physiology, metabolism, pathology, immunology, wound healing, shock and resuscitation, neoplasia, and nutrition) • The diagnosis and preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care of patients with diseases of the alimentary tract; the abdomen and its contents; breast; head and neck; endocrine system; and vascular system (excluding intracranial vessels, the heart, and vessels intrinsic and immediately adjacent thereto) • Responsibility for the comprehensive management of trauma and critically ill patients with underlying surgical conditions 1. Malignant lesions, especially those of the breast, thyroid, and gastrointestinal tract, account for a large percentage of surgical interventions. The extent of the surgical excision of a lesion may be determined only after thorough exploration during a surgical procedure, sometimes scheduled as a diagnostic laparoscopy or as a biopsy and frozen section. a. Although the patient has been informed preoperatively of an anticipated procedure, the unknown factor is cause for apprehension. The circulating nurse should provide comfort while the patient is awake. A biopsy or endoscopic procedure may be performed with the patient under local anesthesia and with or without moderate sedation. b. A definitive open or laparoscopic surgical procedure may be performed on the basis of results of the biopsy and frozen section or endoscopic examination while the patient is under anesthesia. The scrub person should be prepared with two draping and instrument setups, depending on the diagnosis established and the surgeon’s plan for the surgical procedure. Anticipated equipment and supplies should be available without delay. 2. The types of anesthesia administered are as varied as the types of surgical procedures. Blood pressure, pulse, respiration, electrocardiogram (ECG), and pulse oximetry should be monitored for all patients, regardless of the anesthetic used. Personnel responsible for monitoring patients should be qualified to interpret data, assess the patient, and effect corrective action in the event of an untoward reaction. 3. Patients are placed in the supine position for many general surgical procedures. Extra padding and accessory positioning aids should be available for other positions. The average OR bed can accommodate 350 lb of body weight. Obese patients require a suitable bed capable of managing body weight.2 4. Draping for abdominal incisions is usually standardized. Modifications are necessary for other sites, such as the breast or neck. 5. Instrumentation is quite varied and suited to function in a specific anatomic area. For example, gastrointestinal procedures require crushing clamps (e.g., Pean clamps to occlude the intestinal lumen before resection) and atraumatic clamps (e.g., Bainbridge clamps to protect delicate tissues). Included in all procedures are instruments for exposing, dissecting, grasping, clamping, suctioning, and suturing. For atraumatic retraction, various lengths of umbilical tape, hernia tape, or vessel loops may be placed around vessels or other structures to retract them. These materials should be included in the count. 6. Some procedures require minimal access and are adaptable to ambulatory surgery; others are extremely extensive. More complex procedures, such as colectomy and cholecystectomy, are often performed endoscopically and require less in-house hospitalization. 7. The electrosurgical unit (ESU), argon beam coagulator, laser, endoscope, laparoscope, and/or ultrasound transducer may be used during the procedure. 8. In complex open and laparoscopic abdominal and pelvic procedures, the following should be noted: a. Indwelling Foley or ureteral catheters may be inserted preoperatively to decompress the urinary bladder and monitor urinary output. Some surgeons may request the placement of ureteral catheters to stent and outline the ureters for complex dissection of abdominal organs. This will require a sterile cystoscopy setup, stirrups, and a urologist before the general surgery procedure of the abdomen begins. b. Nasogastric (NG) tubes may be passed before or during the surgical procedure to decompress the stomach and bowel. The anesthesia provider inserts the NG tube after the induction of anesthesia. The NG tube may be removed at the end of the surgical procedure. c. After the abdominal cavity is entered, single free 4 × 4 sponges should be removed from the field. They are used only while folded and secured on a sponge stick. Wet or dry laparotomy sponges are used in the abdominal cavity. A small dissector (peanut, cherry, or Kitner) is always clamped in a forceps before being handed to the surgeon. d. Before the peritoneum is incised, suction should be available and ready for immediate use, especially in biliary or intestinal procedures or when fluid or blood may be anticipated in the peritoneal cavity. If a cell saver is used for blood salvage, the suction tips should be kept separate from each other. e. Drains may be exteriorized through a stab wound in the adjacent abdominal wall before closure. A nonabsorbable monofilament suture on a small cutting needle will be used to secure the drain to the skin. Drains are discussed in Chapter 29. f. Contaminated items, such as those used to anastomose intestinal segments, are isolated in a basin on the back table. g. Before closure, the wound is irrigated with warm, sterile, normal saline solution to remove blood and debris. h. Retention sutures may be used to give additional strength to wound closure. Rubber or silicone bumpers or a wound bridge may be used to protect the skin from tension exerted by the adjunct wound closure sutures. Wound closure is discussed in Chapter 28. 9. Assorted sizes of drains, tubes, drainage bags, and wound suction systems should be available. Care is taken to ensure that the patient is not latex sensitive. 10. Irrigating solutions should be body temperature (not to exceed 110° F) when they are used. All radiopaque contrast media, anticoagulants, and solutions on the instrument table and their delivery devices are clearly labeled to avoid any error in administration. Hypodermic syringes with needles are not recapped by hand. Care is taken to monitor the volumes of fluid used for irrigation. 11. Blood loss and urinary output are recorded on the perioperative record. Anesthesia personnel document the amount of intravenous (IV) solution and medications administered during the case. 12. Specimens are carefully labeled and sent for processing as appropriate. Care of specimens is discussed in Chapter 22. The mammary glands are bilateral organs (modified sweat glands) lying in the superficial fascia of the pectoral area (Fig. 33-1). They are attached to the underlying muscles by loose areolar tissue and suspended by Cooper ligaments. The breasts extend from the border of the sternum to the anterior axillary line (tail of Spence) and from approximately the first to the seventh ribs. The breasts are highly vascular. The blood supply is derived laterally from the thoracic branches of the axillary, intercostal, and internal mammary arteries (Fig. 33-2). Venous drainage forms an anastomotic circle around the base of the nipple, with branches draining the circumference of the gland into the axillary and internal mammary veins. Lymphatic drainage follows the same path as the venous system and empties into the thoracoabdominal and lateral thoracic vessels. Innervation arises from the anterior and lateral cutaneous nerves of the thorax. General surgery on the breast for males and females includes diagnostic procedures and those performed for known pathologic disease, such as cancer. Diagnostic techniques include mammography, ultrasonography, fine-needle aspiration (FNA), and the traditional tissue biopsy.7 The average size of lumps found by women who do and do not practice breast self-examination (BSE) is illustrated in Chapter 22 (see Fig. 22-3). All breast masses are considered malignant until proved benign. To determine the exact nature of a mass in the breast, tissue is removed for pathologic examination. The size and location (Fig. 33-3) of the lesion influence the type of biopsy: • Fine-needle aspiration. A 22- or 25-gauge needle attached to a syringe is inserted into the tumor mass. A few cells are aspirated and sent to the pathology laboratory for cytologic studies. This may be performed in conjunction with a mammogram (mammographic breast biopsy) or as an office procedure. FNA also may be used to evacuate fluid from benign cysts. • Core biopsy. For this type of incisional biopsy, a large-bore trocar needle, such as a Tru-Cut or Vim-Silverman biopsy needle, is inserted into the mass. A core of suspected tissue is withdrawn for histologic examination. Any retrieved fluid is also sent to the pathology laboratory. • Stereotactic breast biopsy. The patient is placed prone on a special x-ray table, and her breast is placed in an opening in the table. A computer-guided system is used to digitally locate and pinpoint nonpalpable breast lesions. The biopsy is obtained with a vacuum-assisted Mammotome while the patient is under local anesthesia. • Incisional biopsy. The mass is incised, and a portion is removed for histologic examination. • Excisional biopsy. The entire mass is removed for pathologic study. • Sentinel node biopsy. The breast mass is injected with a radioisotope (technetium) in the radiology department several hours before the planned surgical procedure. In the OR, the tumor is injected with a dye containing isosulfan blue that is taken up by the lymph nodes of the breast. The nodes are excised before the primary mass. A sterile Geiger counter probe is used on the field to locate the areas of radioactivity. The specimens are sent to pathology for immunohistochemical staining. Lead containers are used to house the specimens for 24 hours before the pathologist examines them. • J-wire or needle localization in radiology department. The mass is identified on mammography, and the patient undergoes the insertion of a wire into the mass in the radiology department under fluoroscopy (Fig. 33-4). The wire remains taped in place as the patient is taken to the OR. The mass is excised with the wire intact (Fig. 33-5). The specimen is taken back to the radiology department to be x-rayed as a confirmation that the wire is still in the mass. After the confirmatory x-ray, the specimen is taken to pathology. • Fiberoptic ductoscopy. A flexible 0.9-mm scope with a 0.2-mm working channel is used in the ductal lumens of the breast. Studies have shown that 85% of breast cancer originates in the ductal system in the epithelial lining. The image is enlarged to 200 times by magnification. The scopes are approved for 10 uses each by the U.S Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The ducts may need to be dilated with lacrimal probes before inserting the scope. Specimens can be obtained by this method, and ductal lavage can be performed for cell studies. To minimize disfigurement, many women with early operable breast cancer (a mass less than 5 cm) opt for limited resection followed by radiation and chemotherapy (Fig. 33-6). The difference between tumor and deep tumor-free resection margin remains an important consideration in determining the most appropriate type of mastectomy incision (Table 33-1).1 TABLE 33-1 Breast conservation, the surgical treatment of choice for many women with breast cancer, includes a lumpectomy to excise a primary tumor and axillary node dissection followed by radiation therapy. This approach maintains the appearance and function of the breast (Fig. 33-7). The surgeon may prefer to perform the lumpectomy first, followed by axillary dissection (Fig. 33-8). A subcutaneous mastectomy may be performed for patients with chronic cystic mastitis who have had multiple previous biopsies, for patients with multiple fibroadenomas or hyperplastic duct changes, and for patients with central tumors that are noninvasive in origin. Some patients with a strong family history of breast cancer may have prophylactic mastectomies as a precaution. All breast tissue is removed, but the overlying skin and nipple remain intact.1,7,10 A prosthesis may be inserted at the time of the surgical procedure, depending on the surgeon’s decision and the patient’s wishes. The gallbladder is located in the right upper quadrant in a fossa under and immediately adjacent to the right lobe of the liver (Fig. 33-9). The gallbladder is a thin-walled sac and has a normal capacity of 50 to 75 mL of bile. Bile secreted by the hepatic cells enters the intrahepatic bile ducts and progresses to the common bile duct. When not needed for digestion, bile is diverted through the cystic duct into the gallbladder, where it is stored. When bile is needed, the gallbladder contracts and empties bile into the cystic duct; the bile flows into and through the common duct into the duodenum. Gallstones are concretions of elements of bile, particularly cholesterol (about 50%), and may be found in the gallbladder or in any portion of the extrahepatic biliary duct system.18 Brown stones are usually fatty acids, and black stones comprise inorganic salts. The incidence of stones, referred to as cholelithiasis, increases with age and is more prevalent in women and in people who are obese.18 After palpation of the ducts for stones, the cystic duct and artery are ligated with hemostatic clips and divided. Using blunt dissection, the gallbladder is freed and removed from the liver and its fossa (Fig. 33-10). Some surgeons use ESU and/or neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) or holmium (Ho):YAG laser for sharp dissection and coagulation. Stones removed as part of the specimen should be sent to the pathology department for analysis and documentation. If bile leakage or hemorrhage has been excessive, a sump drain or closed-wound suction drain may be placed in the subhepatic space and brought out through a stab wound after copious intraabdominal irrigation. With a laparoscopic cholecystectomy the patient is supine in a slight to moderate reverse Trendelenburg’s position. A rigid fiberoptic laparoscope is inserted through a sheath into the peritoneal cavity. In conventional laparoscopy multiple trocars are inserted through triangulated puncture wounds in the right upper quadrant: one or two just right of midline, with the uppermost trocar slightly below the xiphoid and costal margin and the other midway to the umbilicus; one laterally in an anterior axillary line above the iliac crest at the costal margin; and another in a midclavicular line slightly above the level of the umbilicus and 2 cm below the rib. The location of puncture sites will vary according to patient size and surgeon preference (Fig. 33-11). Newer technology employs a single incision in the umbilicus and insertion of a flexible multilumen port through which insufflation and additional instruments are placed. Single-incision laparoscopy is discussed in Chapter 32. A camera attached to the laparoscope allows the surgeon to view the manipulation of instruments through the sheaths of these trocars. Viewing monitors are positioned on each side of the head of the OR bed (Fig. 33-12). With this procedure, the fundus of the gallbladder is grasped through one or more lateral ports and held by the assistant. After careful dissection, the surgeon ligates and divides the cystic duct and artery with suture loops or clips. A laser, an ESU, or microscissors may be used to transect these structures. Concomitant exploration of the common duct is often but not routinely performed during cholecystectomy. Curved stone forceps, small malleable scoops, dilators of various sizes, balloon catheters, stone baskets, and nylon brushes are useful in clearing the hepatic and biliary ducts of stones to prevent them from lodging in the duct and causing subsequent obstructive jaundice.4,6 Palpable stones, jaundice with cholangitis, and dilation of the common bile duct are indications for exploration. A T-tube drain may be inserted to stent the duct and provide postoperative drainage. The surgeon may choose other intraoperative techniques to identify unsuspected stones, pathologic conditions, or anatomic variations in the hepatic duct system.4 Unless fluoroscopy is used, a series of three or four x-rays are obtained and displayed in digital format. Before each exposure, the surgeon injects contrast media through a Cholangiocath (a plastic catheter inserted into cystic or common duct), cannula, or direct needle puncture in the common duct (Fig. 33-13). Instruments are removed from the field to the extent possible to minimize the obstruction of structures on the x-rays. The field is covered with a sterile barrier before the x-ray machine or C-arm is positioned over the patient. Sterile x-ray tube and C-arm covers are commercially available. All other radiologic precautions for patient and personnel safety and shielding should be observed. With choledochostomy, a T-tube is used to drain the common bile duct through the abdominal wall. A choledochotomy is the incision of the common bile duct for the exploration and removal of stones. Intraoperative cholangiography may be performed before and after exploration and/or stone removal.4 The duct is irrigated after calculi are removed. Patency of the duct and of the ampulla of Vater is investigated, often through a choledochoscope. If a neoplasm is found during exploration, resectability is determined; many tumors of the liver or pancreas are inoperable. The liver, the largest gland in the body, is divided into left and right segments (or lobes) and is located in the upper right abdominal cavity beneath the diaphragm (Fig. 33-14). Part of the stomach and duodenum and the hepatic flexure of the colon lie directly beneath the liver. A tough fibrous sheath, Glisson capsule, completely covers the organ; the tissue within this capsule is very friable and vascular. The hepatic artery, a branch of the celiac axis, maintains the arterial supply. Blood from the stomach, intestine, spleen, and pancreas is carried to the liver by the portal vein and its branches. The many functions of the liver include forming and secreting bile, which aids digestion; transforming glucose into glycogen, which it stores; and helping to regulate blood volume. The liver is vital for the metabolic functioning of the body. It metabolizes fats, proteins, and carbohydrates; synthesizes cholesterol; excretes bilirubin; and secretes hormones. The liver has remarkable regenerative capacity, and up to 80% of it may be resected with little or no alteration in hepatic function.14

General surgery

Special considerations for general surgery

Breast procedures

Breast biopsy

Stage I

Stage II

Stage III

Stage IV

SIZE

≤1-2 cm

2-5 cm

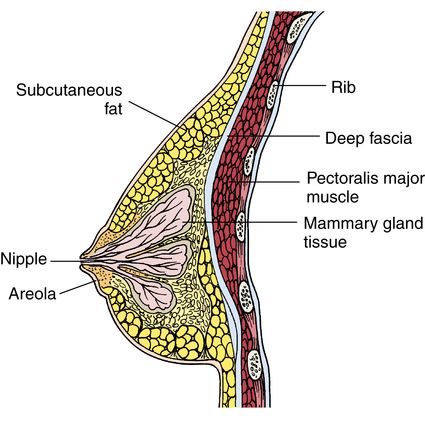

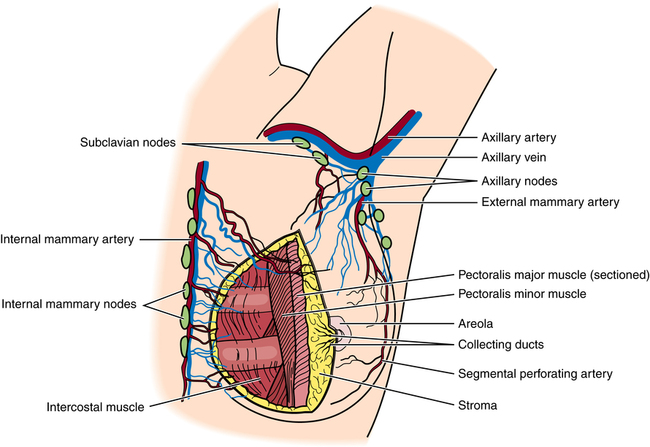

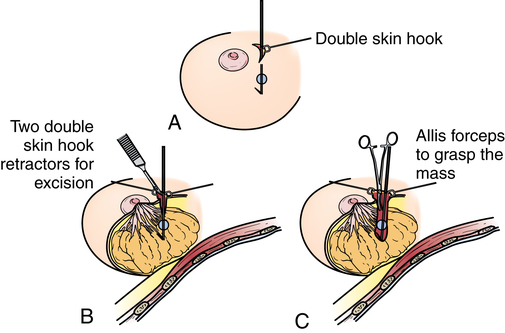

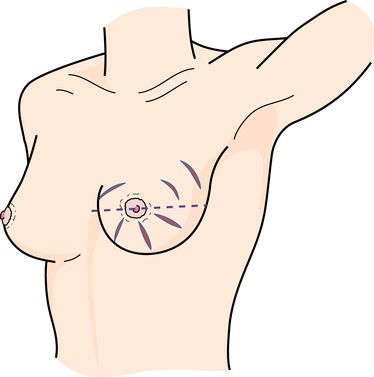

≥5 cm

Large and fully integrated with surrounding tissue

LOCATION

Confined to breast

Breast mass with or without suspicious axillary lymph nodes

Breast mass with palpable, fixed axillary, and/or subclavicular lymph nodes

Distant metastasis; extension to skin

May or may not extend to pectoral fascia or muscle

Mass may be adherent to surrounding tissue

Lymphedema above or below the clavicle

No distant metastasis

No distant metastasis

SURGICAL OPTIONS

Segmental mastectomy

Total mastectomy

Modified or radical mastectomy

Radical or extended radical mastectomy

Breast conservation surgery for stages I and II lumpectomy with axillary node dissection and radiation therapy

Lumpectomy

Simple mastectomy

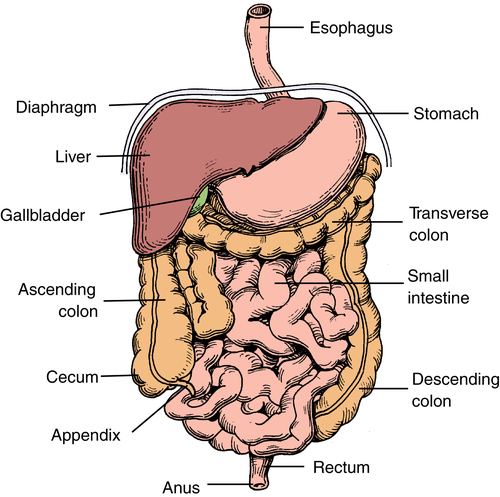

Abdominal procedures

Biliary tract procedures

Cholecystectomy

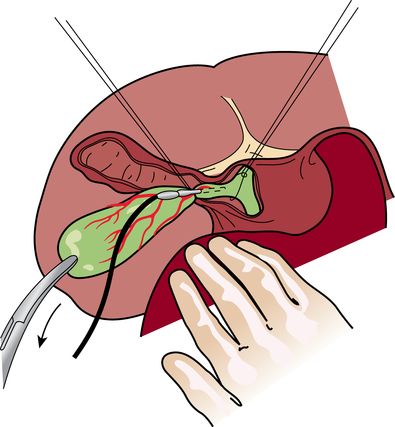

Open abdominal cholecystectomy.

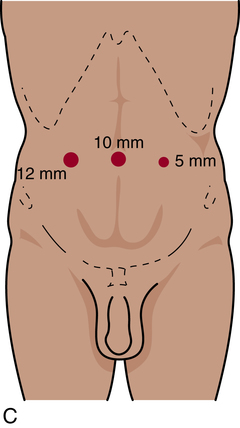

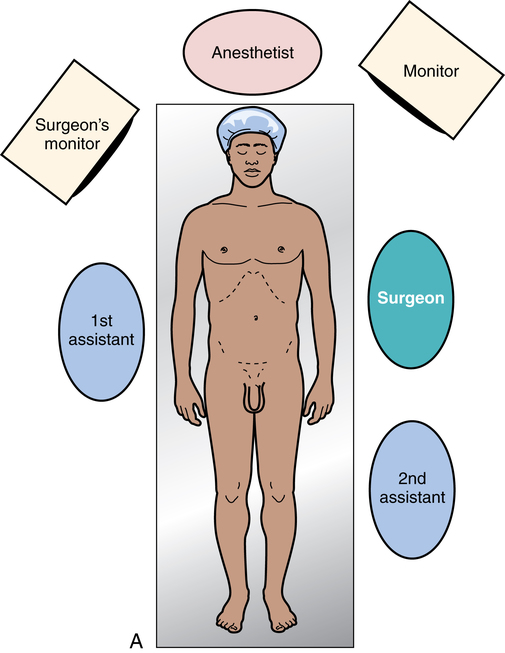

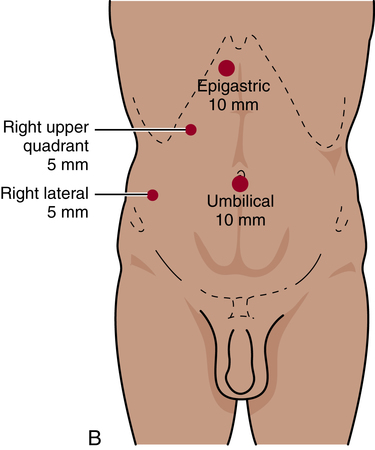

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Common bile duct exploration

Intraoperative cholangiograms.

Choledochostomy and choledochotomy.

Liver procedures

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine

Website

Website