Gastrointestinal System

The GI system has the critical task of supplying essential nutrients to fuel all the physiologic and pathophysiologic activities of the body. Its functioning profoundly affects the quality of life through its impact on overall health. The GI system has two major components: the alimentary canal, or GI tract, and the accessory organs. A malfunction anywhere in the system can produce far-reaching metabolic effects, eventually threatening life itself.

The alimentary canal is a hollow muscular tube that begins in the mouth and ends at the anus. It includes the oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, rectum, and anal canal. Peristalsis propels the ingested material along the tract; sphincters prevent its reflux. Accessory glands and organs include the salivary glands, liver, biliary duct system (gallbladder and bile ducts), and pancreas.

Together, the GI tract and accessory organs serve two major functions: digestion (breaking down food and fluids into simple chemicals that can be absorbed into the bloodstream and transported throughout the body) and elimination of waste products from the body through defecation.

Pathophysiologic changes

Disorders of the GI system typically manifest as vague, nonspecific complaints or problems that reflect disruption in one or more of the system’s functions. For example, movement through the GI tract can be slowed, accelerated, or blocked, and secretion, absorption, or motility can be altered. As a result, one patient may present with several problems, the most common being anorexia, constipation, diarrhea, dysphagia, jaundice, nausea, and vomiting.

ANOREXIA

Anorexia is a loss of appetite or a lack of desire for food. Nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhea may accompany it. Anorexia can result from dysfunction in the GI system or other systems, such as cancer, heart disease, renal disease, or central nervous system dysfunction.

Normally, a physiologic stimulus is responsible for the sensation of hunger. A falling blood glucose level stimulates the hunger center in the hypothalamus; rising blood fat and amino acid levels promote satiety. Hunger is also stimulated by contraction of an empty stomach and suppressed when the GI tract becomes distended, possibly as a result of stimulation of the vagus nerve. Sight, touch, and smell play subtle roles in controlling the appetite center.

In anorexia, the physiologic stimuli are present but the person has no appetite or desire to eat. Slow gastric emptying or gastric stasis can cause anorexia. High levels of neurotransmitters, such as serotonin (may contribute to satiety), and cortisol (may suppress hypothalamic control of hunger) also have been implicated as a cause of anorexia.

CONSTIPATION

Constipation is characterized by hard stools, difficult or infrequent defecation, and a decrease in the number of stools per week. It’s defined

individually because normal bowel habits range from two to three episodes of stool passage per day to one per week. Causes of constipation include dehydration, consumption of a low-bulk diet, a sedentary lifestyle, lack of regular exercise, and frequent repression of the urge to defecate. It’s also an adverse effect of many medications.

individually because normal bowel habits range from two to three episodes of stool passage per day to one per week. Causes of constipation include dehydration, consumption of a low-bulk diet, a sedentary lifestyle, lack of regular exercise, and frequent repression of the urge to defecate. It’s also an adverse effect of many medications.

When a person is dehydrated or delays defecation, more fluid is absorbed from the intestine, the stool becomes harder, and constipation ensues. High-fiber diets cause water to be drawn into the stool by osmosis, thereby keeping stool soft and encouraging movement through the intestine. High-fiber diets also cause intestinal dilation, which stimulates peristalsis. Conversely, a low-fiber diet contributes to constipation.

Elderly patients typically experience a decrease in intestinal motility and a slowing and dulling of neural impulses in the GI tract. Many older persons restrict fluid intake to prevent waking at night to use the bathroom or because they fear incontinence. This places them at risk for dehydration and constipation.

Elderly patients typically experience a decrease in intestinal motility and a slowing and dulling of neural impulses in the GI tract. Many older persons restrict fluid intake to prevent waking at night to use the bathroom or because they fear incontinence. This places them at risk for dehydration and constipation.A sedentary lifestyle, lack of exercise, limitations in physical activity, or inability to engage in physical activity can cause constipation because exercise stimulates the GI tract and promotes defecation. Antacids, opiates, and other drugs that inhibit bowel motility also lead to constipation.

Stress stimulates the sympathetic nervous system, and GI motility slows it. Absence or degeneration in the neural pathways of the large intestine also contributes to constipation. Other conditions, such as spinal cord trauma, multiple sclerosis, intestinal neoplasms, and hypothyroidism, can also cause constipation.

DIARRHEA

Diarrhea is an increase in the fluidity or volume of feces and the frequency of defecation. Factors that affect stool volume and consistency include water content of the colon and the presence of unabsorbed food, unabsorbable material, and intestinal secretions. Largevolume diarrhea is usually the result of an excessive amount of water, secretions, or both in the intestines. Small-volume diarrhea is usually caused by excessive intestinal motility. Diarrhea may also be caused by a parasympathetic stimulation of the intestine initiated by psychological factors, such as fear or stress.

The three major types of diarrhea are osmotic, secretory, and motility:

♦ osmotic diarrhea—The presence of a nonabsorbable substance such as synthetic sugar or increased numbers of osmotic particles in the intestine increases osmotic pressure and draws excess water into the intestine, thereby increasing the weight and volume of the stool.

♦ secretory diarrhea—A pathogen—such as a bacterial toxin (cholera, Clostridium difficile) or enteropathogenic virus—drugs, or presence of a tumor irritates the muscle and mucosal layers of the intestine. The consequent increase in motility and secretions (water, electrolytes, and mucus) results in diarrhea.

♦ motility diarrhea—Inflammation, neuropathy, or obstruction causes a refiex increase in intestinal motility that may expel the irritant or clear the obstruction.

DYSPHAGIA

Dysphagia—difficulty swallowing—can be caused by a mechanical obstruction of the esophagus or by impaired esophageal motility secondary to another disorder. Mechanical obstruction is characterized as intrinsic or extrinsic.

Intrinsic obstructions originate in the esophagus itself. Causes of intrinsic obstructions include tumors, strictures, and diverticular herniations. Extrinsic obstructions originate outside of the esophagus and narrow the lumen by exerting pressure on the esophageal wall. Most extrinsic obstructions result from a tumor.

Distention and spasm at the site of the obstruction during swallowing may cause pain. Upper esophageal obstruction causes pain 2 to 4 seconds after swallowing; lower esophageal obstructions, 10 to 15 seconds after swallowing. If a tumor is present, dysphagia begins with difficulty swallowing solids and eventually progresses to difficulty swallowing semisolids and liquids. Impaired motor function makes both liquids and solids difficult to swallow.

Neural or muscular disorders can also interfere with voluntary swallowing or peristalsis. This is known as functional dysphagia. Causes of functional dysphagia include dermatomyositis, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, or achalasia. (See What happens during swallowing.)

Malfunction of the upper esophageal striated muscles interferes with the voluntary phase of swallowing.

In achalasia, there’s a complete lack of peristalsis within the body of the esophagus. Also, the lower esophageal sphincter doesn’t relax to allow food to enter the stomach. Eventually, accumulated food raises the hydrostatic pressure and forces the sphincter open, and small amounts of food slowly move into the stomach.

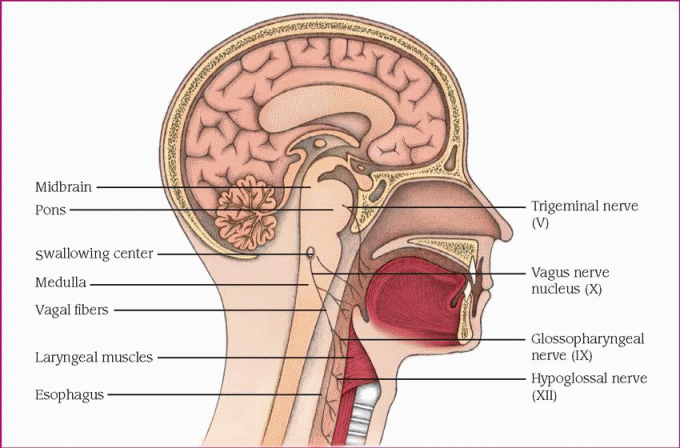

Before peristalsis can begin, the neural pattern to initiate swallowing, illustrated here, must occur:

♦ Food reaching the back of the mouth stimulates swallowing receptors that surround the pharyngeal opening.

♦ The receptors transmit impulses to the brain by way of the sensory portions of the trigeminal (V) and glossopharyngeal (IX) nerves.

♦ The brain’s swallowing center relays motor impulses to the esophagus by way of the trigeminal (V), glossopharyngeal (IX), vagus (X), and hypoglossal (XII) nerves.

♦ Swallowing occurs.

|

JAUNDICE

Jaundice—yellow pigmentation of the skin and sclera—is caused by an excess accumulation of bilirubin in the blood. Bilirubin, a product of red blood cell (RBC) breakdown, accumulates when production exceeds metabolism and excretion. This imbalance can result from excessive release of bilirubin precursors into the bloodstream or from impairment of its hepatic uptake, metabolism, or excretion. (See Jaundice: Impaired bilirubin metabolism, page 322.) Jaundice occurs when bilirubin levels exceed 2.0 to 2.5 mg/dl, which is about twice the upper limit of the normal range. Lower levels of bilirubin may cause detectable jaundice in patients with fair skin, and jaundice may be difficult to detect in patients with dark skin.

Jaundice in dark-skinned persons may appear as yellow staining in the sclera, hard palate, and palmar or plantar surfaces.

Jaundice in dark-skinned persons may appear as yellow staining in the sclera, hard palate, and palmar or plantar surfaces.The three main types of jaundice are hemolytic, hepatocellular, and obstructive:

♦ hemolytic (or prehepatic) jaundice—When RBC lysis exceeds the liver’s capacity to conjugate bilirubin (binding bilirubin to a polar group makes it water soluble and able to be excreted by the kidneys), hemolytic jaundice occurs. Causes include transfusion reactions, sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, and autoimmune disease.

♦ hepatocellular (or hepatic) jaundice—Hepatocyte dysfunction limits uptake and conjugation of bilirubin. Liver dysfunction can occur in hepatitis, cancer, cirrhosis, or congenital disorders, and also can be caused by some drugs.

♦ obstructive (or posthepatic) jaundice—When the flow of bile out of the liver (through the hepatic duct) or through the common bile duct is blocked, the liver can conjugate bilirubin, but the bilirubin can’t reach the small intestine.

Blockage of the hepatic duct by calculi or a tumor is considered an intrahepatic cause of obstructive jaundice. A blocked common bile duct is an extrahepatic cause that may be attributed to gallstones or a tumor.

Blockage of the hepatic duct by calculi or a tumor is considered an intrahepatic cause of obstructive jaundice. A blocked common bile duct is an extrahepatic cause that may be attributed to gallstones or a tumor.

Jaundice occurs in three forms: prehepatic, hepatic, and posthepatic. In all three, bilirubin levels in the blood increase.

Prehepatic jaundice

Certain conditions and disorders, such as transfusion reactions and sickle cell anemia, cause massive hemolysis.

♦ Red blood cells rupture faster than the liver can conjugate bilirubin.

♦ Large amounts of unconjugated bilirubin pass into the blood.

♦ Intestinal enzymes convert bilirubin to watersoluble urobilinogen for excretion in urine and stools. (Unconjugated bilirubin is insoluble in water, so it can’t be directly secreted in urine.)

Hepatic jaundice

The liver becomes unable to conjugate or excrete bilirubin, leading to increased blood levels of conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin. This occurs in such disorders as hepatitis, cirrhosis, and metastatic cancer, and during prolonged use of drugs metabolized by the liver.

Posthepatic jaundice

In biliary and pancreatic disorders, bilirubin forms at its normal rate.

♦ Inflammation, scar tissue, tumor, or gallstones block the flow of bile into the intestines.

♦ Water-soluble conjugated bilirubin accumulates in the blood.

♦ The bilirubin is excreted in the urine.

NAUSEA

Nausea is feeling the urge to vomit. It may occur independently of vomiting, or it may precede or accompany it. Specific neural pathways haven’t been identified, but increased salivation, diminished functional activities of the stomach, and altered small intestinal motility have been associated with nausea. Nausea may also be stimulated by high brain centers.

VOMITING

Vomiting is the forceful oral expulsion of gastric contents. The gastric musculature provides the ejection force. The gastric fundus and gastroesophageal sphincter relax, and forceful contractions of the diaphragm and abdominal wall muscles increase intra-abdominal pressure. This, combined with the annular contraction of the gastric pylorus, forces gastric contents into the esophagus. Increased intrathoracic pressure then moves the gastric content from the esophagus to the mouth.

Vomiting is controlled by two centers in the medulla: the vomiting center and the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ). The vomiting center initiates the actual act of vomiting. It’s stimulated by the GI tract, from higher brain stem and cortical centers, and from the CTZ. The CTZ can’t induce vomiting by itself. Various stimuli or drugs activate the zone, such as apomorphine, levodopa, digoxin, bacterial toxins, radiation, and metabolic abnormalities. The activated zone sends impulses to the medullary vomiting center, and the following sequence begins:

♦ The abdominal muscles and diaphragm contract.

♦ Reverse peristalsis begins, causing intestinal material to flow back into the stomach, distending it.

♦ The stomach pushes the diaphragm into the thoracic cavity, raising the intrathoracic pressure.

♦ The pressure forces the upper esophageal sphincter open, the glottis closes, and the soft palate blocks the nasopharynx.

♦ The pressure also forces the material up through the sphincter and out through the mouth.

Nausea and vomiting are manifestations of other disorders, such as acute abdominal emergencies, infections of the intestinal tract, central nervous system disorders, myocardial infarction, heart failure, metabolic and endocrinologic disorders, or as the adverse effect of many drugs. Nausea and vomiting can also be present in pregnancy. Vomiting may also be psychogenic, resulting from emotional or psychological disturbance.

Disorders

This section discusses disorders of the GI system, some of which are life-threatening. They include appendicitis, cholecystitis, cirrhosis, Crohn’s disease, diverticular disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, hemorrhoids, hepatitis

(nonviral and viral), Hirschsprung’s disease, hyperbilirubinemia, inguinal hernia, intestinal obstruction, irritable bowel syndrome, liver failure, malabsorption, pancreatitis, peptic ulcers, polyps (intestinal), and ulcerative colitis.

(nonviral and viral), Hirschsprung’s disease, hyperbilirubinemia, inguinal hernia, intestinal obstruction, irritable bowel syndrome, liver failure, malabsorption, pancreatitis, peptic ulcers, polyps (intestinal), and ulcerative colitis.

APPENDICITIS

The most common disease requiring emergency surgery, appendicitis is inflammation and obstruction of the vermiform appendix (a blind pouch attached to the cecum). Appendicitis may occur at any age, with peak incidence occurring from the late teens to the early 20s. It’s more prevalent in men. Since the advent of antibiotics, the incidence and mortality rate from appendicitis have declined; if untreated, this disease is invariably fatal.

Causes

♦ Barium ingestion

♦ Fecal mass

♦ Mucosal ulceration

♦ Stricture

♦ Viral infection

Pathophysiology

Mucosal ulceration triggers inflammation, which temporarily obstructs the appendix. The obstruction blocks mucus outflow. Pressure in the now distended appendix increases, and the appendix contracts. Bacteria multiply, and inflammation and pressure continue to increase, restricting blood flow to the pouch and causing severe abdominal pain.

Signs and symptoms

♦ Abdominal pain, caused by inflammation of the appendix and bowel obstruction and distention, begins in the epigastric region, and then shifts to the right lower quadrant

♦ Anorexia after the onset of pain

♦ Nausea or vomiting caused by the inflammation

♦ Low-grade fever from systemic manifestation of inflammation and leukocytosis

♦ Tenderness from inflammation, positive rebound tenderness and psoas and obturator signs

Complications

♦ Wound infection

♦ Intra-abdominal abscess

♦ Fecal fistula

♦ Intestinal obstruction

♦ Incisional hernia

♦ Peritonitis

Diagnosis

♦ White blood cell count is moderately high with an increased number of immature cells.

♦ X-ray with radiographic contrast agent reveals failure of the appendix to fill with contrast.

Treatment

♦ Maintenance of nothing by mouth (NPO) status until surgery

♦ Fowler’s position to aid in pain relief

♦ GI intubation for decompression

♦ Appendectomy

♦ An antibiotic to treat infection if peritonitis occurs

♦ Parental replacement of fluid and electrolytes to reverse possible dehydration resulting from surgery or nausea and vomiting

Special considerations

If appendicitis is suspected, or during preparation for appendectomy:

♦ Administer I.V. fluids to prevent dehydration. Never administer a cathartic or an enema, which may rupture the appendix. Maintain NPO status, and administer the analgesic judiciously because it may mask symptoms.

♦ To lessen pain, place the patient in Fowler’s position. Never apply heat to the right lower abdomen; this may cause the appendix to rupture. An ice bag may be used for pain relief.

After appendectomy

♦ Monitor vital signs and intake and output. Give an analgesic as ordered.

♦ Encourage the patient to cough, breathe deeply, and turn frequently to prevent pulmonary complications.

♦ Document bowel sounds, passing of flatus, and bowel movements. In a patient whose nausea and abdominal rigidity have subsided, these signs indicate readiness to resume taking in oral fluids.

♦ Watch closely for possible surgical complications. Continuing pain and fever may signal an abscess. The complaint that “something gave way” may mean wound dehiscence. If an abscess or peritonitis develops, incision and drainage may be necessary. Frequently assess the dressing for wound drainage.

♦ Help the patient ambulate as soon as possible after surgery.

♦ In appendicitis complicated by peritonitis, a nasogastric tube may be needed to decompress the stomach and reduce nausea and vomiting. If so, record drainage and give good mouth and nose care.

CHOLECYSTITIS

Cholecystitis—acute or chronic inflammation causing painful distention of the gallbladder—is

usually associated with a gallstone impacted in the cystic duct.

usually associated with a gallstone impacted in the cystic duct.

Cholecystitis accounts for 10% to 25% of all patients requiring gallbladder surgery. The acute form is most common among middle-aged women; the chronic form, among elderly people. The prognosis is good with treatment.

Causes

♦ Abnormal metabolism of cholesterol and bile salts

♦ Gallstones (the most common cause)

♦ Poor or absent blood flow to the gallbladder

Pathophysiology

In acute cholecystitis, inflammation of the gallbladder wall usually develops after a gallstone lodges in the cystic duct. (See Understanding gallstone formation, pages 326 and 327.) When bile flow is blocked, the gallbladder becomes inflamed and distended. Bacterial growth, usually Escherichia coli, may contribute to the inflammation. Edema of the gallbladder (and sometimes the cystic duct) obstructs bile flow, which chemically irritates the gallbladder. Cells in the gallbladder wall may become oxygen starved and die as the distended organ presses on vessels and impairs blood flow. The dead cells slough off, and an exudate covers ulcerated areas, causing the gallbladder to adhere to surrounding structures.

Signs and symptoms

♦ Acute abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant that may radiate to the back, between the shoulders, or to the front of the chest secondary to inflammation and irritation of nerve fibers

♦ Colic due to the passage of gallstones along the bile duct

♦ Nausea and vomiting triggered by the inflammatory response

♦ Chills related to fever

♦ Low-grade fever secondary to inflammation

♦ Jaundice from obstruction of the common bile duct by calculi

♦ Previous attack of biliary colic or cholecystitis

Complications

♦ Perforation and abscess formation

♦ Fistula formation

♦ Gangrene

♦ Empyema

♦ Cholangitis

♦ Hepatitis

♦ Pancreatitis

♦ Gallstone ileus

♦ Carcinoma

Diagnosis

♦ Ultrasonography detects gallstones as small as 2 mm and distinguishes between obstructive and nonobstructive jaundice.

♦ X-ray reveals gallstones if they contain enough calcium to be radiopaque; also helps disclose porcelain gallbladder (hard, brittle gallbladder due to calcium deposited in wall), limy bile, and gallstone ileus.

♦ Technetium-labeled scan reveals cystic duct obstruction and acute or chronic cholecystitis if ultrasound doesn’t visualize the gallbladder.

♦ Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography supports the diagnosis of obstructive jaundice and reveals calculi in the ducts.

♦ Levels of serum alkaline phosphate, lactate dehydrogenase, aspartate aminotransferase, and total bilirubin are high; the serum amylase level slightly elevated, and the icteric index is elevated.

♦ The white blood cell count is slightly elevated during a cholecystitis attack.

Treatment

♦ Cholecystectomy to surgically remove the inflamed gallbladder (laparoscopic or an “open” procedure)

♦ Choledochostomy to surgically create an opening into the common bile duct for drainage

♦ Percutaneous transhepatic cholecystostomy

♦ Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for removal of gallstones

♦ Lithotripsy to break up gallstones and relieve obstruction

♦ Oral ursodiol or chenodiol to dissolve calculi

♦ Contact dissolution therapy using methyl terbutyl ether injected directly into the stone for dissolution in 1 to 3 days (an experimental procedure because the drug is highly flammable and toxic)

♦ Low-fat diet to prevent attacks

♦ Vitamin K to relieve itching, jaundice, and bleeding tendencies due to vitamin K deficiencies

♦ An antibiotic for use during acute attack for treatment of infection

♦ Nasogastric tube insertion during acute attack for abdominal decompression

Special considerations

Patient care for cholecystitis focuses on supportive care and close postoperative observation.

♦ Before surgery, teach the patient to deep breathe, cough, expectorate, and perform leg exercises that are necessary after surgery. Also teach splinting, repositioning, and ambulation techniques. Explain the procedures that will be performed before, during, and after surgery to

help ease the patient’s anxiety and to help ensure his cooperation.

help ease the patient’s anxiety and to help ensure his cooperation.

♦ After surgery, monitor vital signs for signs of bleeding, infection, or atelectasis.

♦ Evaluate the incision site for bleeding. Serosanguineous drainage is common during the first 24 to 48 hours if the patient has a wound drain. If, after a choledochostomy, a T-tube drain is placed in the duct and attached to a drainage bag, make sure the drainage tube has no kinks. Also, check that the connecting tubing from the T tube is well secured to the patient to prevent dislodgment.

♦ Measure and record T-tube drainage daily (200 to 300 ml is normal).

♦ Teach patients who will be discharged with a T tube how to perform dressing changes and routine skin care.

♦ Monitor intake and output. Allow the patient nothing by mouth for 24 to 48 hours or until bowel sounds return and nausea and vomiting cease (postoperative nausea may indicate a full bladder).

♦ If the patient doesn’t void within 8 hours (or if the amount voided is inadequate based on I.V. fluid intake), percuss over the symphysis pubis for bladder distention (especially in patients receiving an anticholinergic). Patients who have had a laparoscopic cholecystectomy may be discharged the same day or within 24 hours after surgery. These patients should have minimal pain, be able to tolerate a regular diet within 24 hours after surgery, and be able to return to normal activity within 1 week.

♦ Encourage deep-breathing and leg exercises every hour. The patient should ambulate after surgery. Provide elastic stockings to support leg muscles and promote venous blood flow, thus preventing stasis and clot formation.

♦ Evaluate the location, duration, and character of pain. Administer adequate medication to relieve pain, especially before such activities as deep breathing and ambulation, which increase pain.

♦ At discharge, advise the patient against heavy lifting or straining for 6 weeks. Urge him to walk daily. Tell him that food restrictions are unnecessary unless he has an intolerance to a specific food or some underlying condition (such as diabetes, atherosclerosis, or obesity) that requires such restriction.

♦ Instruct the patient to notify the surgeon if he has pain for more than 24 hours, anorexia, nausea or vomiting, fever, or tenderness in the abdominal area or if he notices jaundice, because these may indicate a biliary tract injury from the cholestectomy, requiring immediate attention.

CIRRHOSIS

Cirrhosis is a chronic disease characterized by diffuse destruction and fibrotic regeneration of hepatic cells. As necrotic tissue yields to fibrosis, this disease damages liver tissue and normal vasculature, impairs blood and lymph flow, and ultimately causes hepatic insufficiency. It’s twice as common in men as in women, and it’s especially prevalent among malnourished persons older than age 50 with chronic alcoholism. Mortality is high; many patients die within 5 years of onset.

Causes

Cirrhosis may be a result of a wide range of diseases. The following clinical types of cirrhosis reflect its diverse etiology.

Hepatocellular disease

This group includes the following disorders:

♦ Postnecrotic cirrhosis accounts for 10% to 30% of patients and stems from various types of hepatitis (such as Types A, B, C, D viral hepatitis) or toxic exposures.

♦ Laënnec’s cirrhosis, also called portal, nutritional, or alcoholic cirrhosis, is the most common type and is primarily caused by hepatitis C and alcoholism. Liver damage results from malnutrition (especially dietary protein) and longterm alcohol use. Fibrous tissue forms in portal areas and around central veins.

♦ Autoimmune disease, such as sarcoidosis or chronic inflammatory bowel disease, may cause cirrhosis.

Cholestatic diseases

This group includes diseases of the biliary tree (biliary cirrhosis resulting from bile duct diseases suppressing bile flow) and sclerosing cholangitis.

Metabolic diseases

This group includes such disorders as Wilson’s disease, alpha1-antitrypsin, and hemochromatosis (pigment cirrhosis).

Other types of cirrhosis

Other types of cirrhosis include Budd-Chiari syndrome (epigastric pain, liver enlargement, and ascites due to hepatic vein obstruction), cardiac cirrhosis, and cryptogenic cirrhosis. Cardiac cirrhosis is rare; the liver damage results from right-sided heart failure. Cryptogenic refers to cirrhosis of unknown etiology.

Pathophysiology

Cirrhosis begins with hepatic scarring or fibrosis. The scar begins as an increase in extracellular

matrix components—fibril-forming collagens, proteoglycans, fibronectin, and hyaluronic acid. The site of collagen deposition varies with the cause. Hepatocyte function is eventually impaired as the matrix changes. Fat-storing cells are believed to be the source of the new matrix components. Contraction of these cells may also contribute to disruption of the lobular architecture and obstruction of the flow of blood or bile. Cellular changes producing bands of scar tissue also disrupt the lobular structure.

matrix components—fibril-forming collagens, proteoglycans, fibronectin, and hyaluronic acid. The site of collagen deposition varies with the cause. Hepatocyte function is eventually impaired as the matrix changes. Fat-storing cells are believed to be the source of the new matrix components. Contraction of these cells may also contribute to disruption of the lobular architecture and obstruction of the flow of blood or bile. Cellular changes producing bands of scar tissue also disrupt the lobular structure.

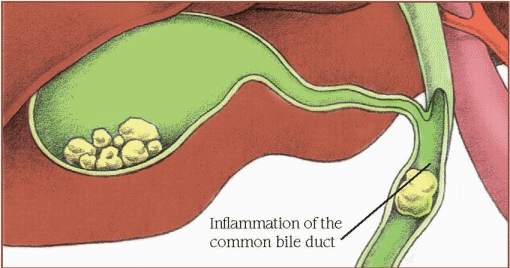

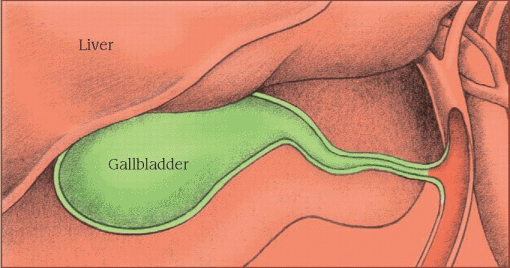

Abnormal metabolism of cholesterol and bile salts plays an important role in gallstone formation. The liver makes bile continuously. The gallbladder concentrates and stores it until the duodenum signals it needs it to help digest fat. Changes in the composition of bile may allow gallstones to form. Changes to the absorptive ability of the gallbladder lining may also contribute to gallstone formation.

Inside the liver

Certain conditions, such as age, obesity, and estrogen imbalance, cause the liver to secrete bile that’s abnormally high in cholesterol or lacking the proper concentration of bile salts.

|

Inside the gallbladder

When the gallbladder concentrates this bile, inflammation may occur. Excessive reabsorption of water and bile salts makes the bile less soluble. Cholesterol, calcium, and bilirubin precipitate into gallstones.

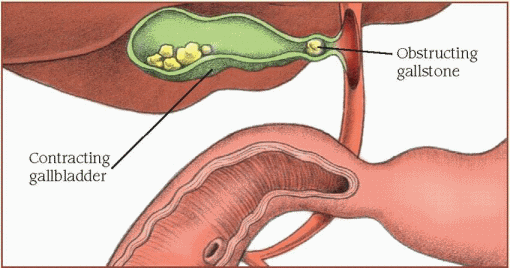

Fat entering the duodenum causes the intestinal mucosa to secrete the hormone cholecystokinin, which stimulates the gallbladder to contract and empty. If a stone lodges in the cystic duct, the gallbladder contracts but can’t empty.

|

Inside the common bile duct

If a stone lodges in the common bile duct, the bile can’t flow into the duodenum. Bilirubin is absorbed into the blood and causes jaundice.

Biliary narrowing and swelling of the tissue around the stone can also cause irritation and inflammation of the common bile duct.

|

Signs and symptoms

Early stages

♦ Anorexia from distaste for certain foods

♦ Nausea and vomiting from inflammatory response and systemic effects of liver inflammation

♦ Diarrhea from malabsorption

♦ Dull abdominal ache from liver inflammation

Late stages

♦ Respiratory—pleural effusion, limited thoracic expansion due to abdominal ascites; interferes with efficient gas exchange, which causes hypoxia

♦ Central nervous system—progressive signs or symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy, including lethargy, mental changes, slurred speech, asterixis, peripheral neuritis, paranoia, hallucinations, extreme obtundation, and coma—secondary to the failure of the metabolism of ammonia into urea and consequent delivery of toxic ammonia to the brain

♦ Hematologic—bleeding tendencies (nosebleeds, easy bruising, bleeding gums), splenomegaly, anemia resulting from thrombocytopenia (secondary to splenomegaly and decreased vitamin K absorption), and portal hypertension

♦ Endocrine—testicular atrophy, menstrual irregularities, gynecomastia, and loss of chest and axillary hair from decreased hormone metabolism

♦ Skin—abnormal pigmentation, spider angiomas, palmar erythema, and jaundice related to impaired hepatic function; severe pruritus secondary to jaundice from bilirubinemia; extreme dryness and poor tissue turgor related to malnutrition

♦ Hepatic—jaundice from decreased bilirubin metabolism; hepatomegaly secondary to liver scarring and portal hypertension; ascites and edema of the legs from portal hypertension and decreased plasma proteins; hepatic encephalopathy from ammonia toxicity; and hepatorenal

syndrome from advanced liver disease and subsequent renal failure

syndrome from advanced liver disease and subsequent renal failure

♦ Miscellaneous—musty breath secondary to ammonia buildup; enlarged superficial abdominal veins due to portal hypertension; pain in the right upper abdominal quadrant that worsens when patient sits up or leans forward, due to inflammation and irritation of area nerve fibers; palpable liver or spleen due to organomegaly; temperature of 101° to 103° F (38.3° to 39.4° C) due to inflammatory response; hemorrhage from esophageal varices resulting from portal hypertension. (See What happens in portal hypertension.)

Complications

♦ Respiratory compromise

♦ Ascites

♦ Portal hypertension

♦ Jaundice

♦ Coagulopathy

♦ Hepatic encephalopathy

♦ Bleeding esophageal varices; acute GI bleeding

♦ Liver failure

♦ Renal failure

Diagnosis

♦ Liver biopsy reveals tissue destruction and fibrosis.

♦ Abdominal X-ray shows enlarged liver, cysts, or gas within the biliary tract or liver, liver calcification, and massive fluid accumulation (ascites).

♦ Computed tomography and liver scans show liver size, abnormal masses, and hepatic blood flow and obstruction.

♦ Esophagogastroduodenoscopy reveals bleeding esophageal varices, stomach irritation or ulceration, or duodenal bleeding and irritation.

♦ Blood studies reveal elevated levels of liver enzymes, total serum bilirubin, and indirect bilirubin; decreased levels of total serum albumin, protein, hemoglobin, and electrolytes; prolonged prothrombin time; decreased hematocrit; and deficiency of vitamins A, C, and K.

♦ Urine studies show increased bilirubin and urobilirubinogen levels.

♦ Fecal studies show a decreased fecal urobilirubinogen level.

Treatment

♦ Vitamins and nutritional supplements to help heal damaged liver cells and improve nutritional status

♦ An antacid to reduce gastric distress and decrease the potential for GI bleeding

♦ A potassium-sparing diuretic to reduce fluid accumulation

♦ Vasopressin to treat esophageal varices

♦ Esophagogastric intubation with multilumen tubes to control bleeding from esophageal varices or other hemorrhage sites by using balloons to exert pressure on the bleeding site

♦ Gastric lavage until the contents are clear; with an antacid and a histamine antagonist if the bleeding is secondary to a gastric ulcer

♦ Esophageal balloon tamponade to compress bleeding vessels and stop blood loss from esophageal varices

♦ Paracentesis to relieve abdominal pressure and remove ascitic fluid

♦ Surgical shunt placement to divert ascites into venous circulation, leading to weight loss, decreased abdominal girth, increased sodium excretion from the kidneys, and improved urine output

♦ A sclerosing agent injected into oozing vessels to cause clotting and sclerosis

♦ Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (a radiologic procedure) to reduce pressure in the varices, preventing them from bleeding

♦ Insertion of portosystemic shunts to control bleeding from esophageal varices and decrease portal hypertension (diverts a portion of the portal vein blood flow away from the liver; seldom performed)

Special considerations

Patients with cirrhosis need close observation, intensive supportive care, and sound nutritional counseling.

♦ Check skin, gums, stools, and vomitus regularly for bleeding. Apply pressure to injection sites to prevent bleeding. Warn the patient against taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, straining at stool, and blowing his nose or sneezing too vigorously. Suggest using an electric razor and soft toothbrush.

♦ Observe the patient closely for signs of behavioral or personality changes. Report increasing stupor, lethargy, hallucinations, or neuromuscular dysfunction. Awaken the patient periodically to determine level of consciousness. Watch for asterixis, a sign of developing hepatic encephalopathy.

♦ To assess fluid retention, weigh the patient and measure abdominal girth at least daily; inspect ankles and sacrum for dependent edema; and accurately record intake and output. Carefully evaluate the patient before, during, and after paracentesis; this drastic loss of fluid may induce shock.

♦ To prevent skin breakdown associated with edema and pruritus, avoid using soap when you bathe the patient; instead, use lubricating lotion or moisturizing agents. Handle the patient gently, and turn and reposition him often to keep his skin intact.

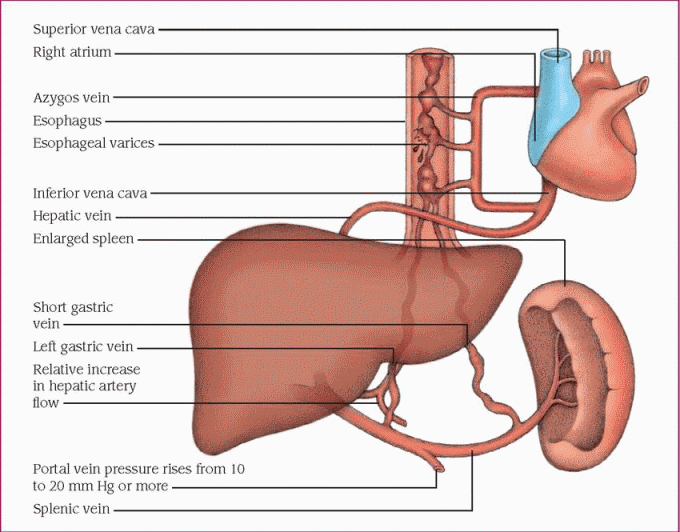

Portal hypertension (elevated pressure in the portal vein) occurs when blood flow meets increased resistance. This common result of cirrhosis may also stem from mechanical obstruction and occlusion of the hepatic veins (Budd-Chiari syndrome).

As the pressure in the portal vein rises, blood backs up into the spleen and flows through collateral channels to the venous system, bypassing the liver. Thus, portal hypertension causes:

♦ splenomegaly with thrombocytopenia

|

♦ dilated collateral veins (esophageal varices, hemorrhoids, or prominent abdominal veins)

♦ ascites.

In many patients, the first sign of portal hypertension is bleeding esophageal varices (dilated tortuous veins in the submucosa of the lower esophagus).

Esophageal varices commonly cause massive hematemesis, requiring emergency care to control hemorrhage and prevent hypovolemic shock.

♦ Tell the patient that rest and good nutrition will conserve energy and decrease metabolic demands on the liver. Urge him to eat frequent small meals. Stress the need to avoid infections and abstain from alcohol. Refer the patient to Alcoholics Anonymous, if necessary.

CROHN’S DISEASE

Crohn’s disease, also known as regional enteritis or granulomatous colitis, is inflammation of any part of the GI tract (usually the proximal portion of the colon and less commonly the terminal ileum), extending through all layers of the intestinal wall. It may also involve regional lymph nodes and the mesentery. Crohn’s disease is most prevalent in adults between ages 20 and 40.

Causes

The exact cause is unknown but conditions that may contribute include:

♦ allergies

♦ genetic predisposition

♦ immune disorders

♦ infection

♦ lymphatic obstruction.

Crohn’s disease sometimes occurs in identical twins, and 10% to 20% of patients with the disease have one or more affected relatives.

Crohn’s disease sometimes occurs in identical twins, and 10% to 20% of patients with the disease have one or more affected relatives.Researchers recently found a mutation in the gene known as NOD2. The mutation is twice as common in patients with Crohn’s disease when compared with the general population. It seems to alter the body’s ability to combat bacteria. Currently, there’s no practical method to screen for the presence of this genetic mutation.

Pathophysiology

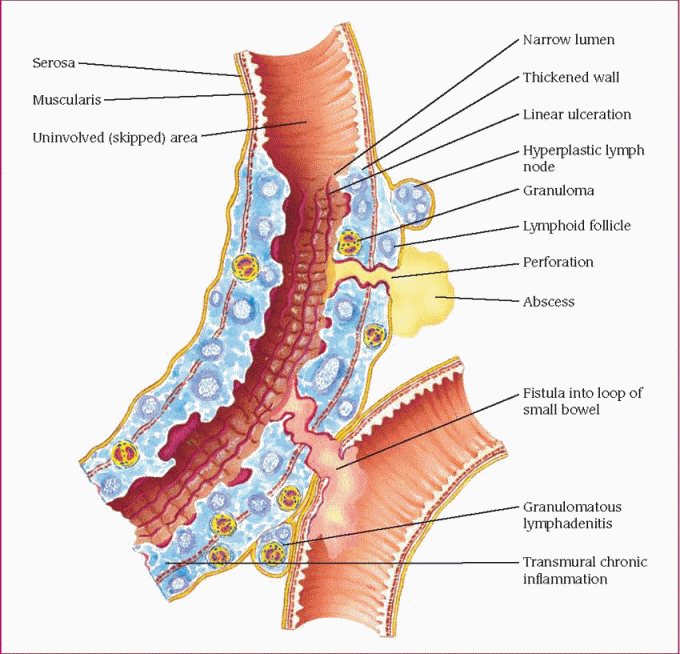

Whatever the cause of Crohn’s disease, inflammation spreads slowly and progressively. Enlarged lymph nodes block lymph flow in the submucosa. Lymphatic obstruction leads to edema, mucosal ulceration and fissures, abscesses, and sometimes granulomas. Mucosal ulcerations are called “skipping lesions” because they aren’t continuous, as in ulcerative colitis.

Oval, elevated patches of closely packed lymph follicles in the lining of the small intestine— called Peyer’s patches—become inflamed. Subsequent fibrosis thickens the bowel wall and causes stenosis, or narrowing of the lumen. (See Bowel changes in Crohn’s disease.) The serous membrane becomes inflamed (serositis), inflamed bowel loops adhere to other diseased or normal loops, and diseased bowel segments become interspersed with healthy ones. Finally, diseased parts of the bowel become thicker, narrower, and shorter.

Signs and symptoms

♦ Steady, colicky pain in the right lower quadrant due to acute inflammation and nerve fiber irritation

♦ Cramping due to acute inflammation

♦ Tenderness due to acute inflammation

♦ Palpable mass in the right lower quadrant due to bowel thickening

♦ Weight loss secondary to diarrhea and malabsorption

♦ Diarrhea due to bile salt malabsorption, loss of healthy intestinal surface area, and bacterial growth

♦ Steatorrhea secondary to fat malabsorption

♦ Bloody stools secondary to bleeding from inflammation and ulceration

Complications

♦ Anal fistula

♦ Perineal abscess

♦ Fistulas to the bladder or vagina or to the skin in an old scar area

♦ Intestinal obstruction

♦ Nutrient deficiencies from poor digestion and malabsorption of bile salts and vitamin B12

♦ Fluid imbalances

Diagnosis

♦ Fecal occult blood test reveals minute amounts of blood in stools.

♦ Small bowel X-ray with barium shows irregular mucosa, ulceration, and stiffening.

♦ Barium enema reveals the string sign (segments of stricture separated by normal bowel) and possibly fissures and narrowing of the bowel.

♦ Sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy reveal patchy areas of inflammation (helps to rule out ulcerative colitis), with cobblestone-like mucosal surface. With colon involvement, ulcers may be seen.

♦ Computed tomography scan detects abscesses.

♦ Video capsule endoscopy identifies mild, early abnormalities from Crohn’s disease and can confirm Crohn’s disease during normal barium X-ray.

♦ Biopsy reveals granulomas in up to one-half of all specimens.

♦ Blood tests reveal increased white blood cell count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate and decreased potassium, calcium, magnesium, and hemoglobin levels.

Treatment

♦ Sulfasalazine or 5-aminosalicylate to reduce inflammation

♦ A corticosteroid to reduce inflammation and, subsequently, diarrhea, pain, and bleeding

♦ Immunomodulators, such as mercaptopurine and azathioprine, to suppress the response to antigens

♦ Antitumor necrosis factor agent infliximab to treat moderate to severe disease that doesn’t respond to conventional therapy

♦ Metronidazole to treat perianal complications

♦ An antidiarrheal to combat diarrhea (not used in patients with significant bowel obstruction)

♦ An opioid analgesic to control pain and diarrhea

♦ Stress reduction and reduced physical activity to rest the bowel and allow it to heal

♦ Vitamin supplements to replace and compensate for the bowel’s inability to absorb vitamins

♦ Dietary changes (elimination of fruits, vegetables, high-fiber foods, dairy products, spicy and fatty foods, foods that irritate the mucosa, carbonated or caffeinated beverages, and other foods or liquids that stimulate excessive intestinal activity) to decrease bowel activity while still providing adequate nutrition

As Crohn’s disease progresses, fibrosis thickens the bowel wall and narrows the lumen. Narrowing — or stenosis — can occur in any part of the intestine and cause varying degrees of intestinal obstruction. At first, the mucosa may appear normal, but as the disease progresses it takes on a “cobblestone” appearance as shown.

|

♦ Surgery, if necessary, to repair bowel perforation, drain abscesses, and correct massive hemorrhage, fistulas, or acute intestinal obstruction; colectomy with ileostomy in patients with extensive disease of the large intestine and rectum

Special considerations

Although treatment is based largely on symptoms, you should monitor the patient’s status carefully for signs and symptoms of worsening.

♦ Record fluid intake and output (including the amount of stool), and weigh the patient daily. Watch for dehydration and maintain fluid and electrolyte balance. Be alert for signs of intestinal bleeding (bloody stools); check stools daily for occult blood.

♦ If the patient is receiving a steroid, watch for adverse reactions, such as GI bleeding. Remember that steroids can mask signs of infection.

♦ Check the hemoglobin level and hematocrit regularly. Give an iron supplement and a blood transfusion, as ordered.

♦ Give an analgesic as ordered.

♦ Provide good patient hygiene and meticulous mouth care if the patient is restricted to nothing by mouth. After each bowel movement, give good skin care. Always keep a clean, covered

bedpan within the patient’s reach. Ventilate the room to eliminate odors.

bedpan within the patient’s reach. Ventilate the room to eliminate odors.

♦ Observe the patient for fever and pain or pneumaturia, which may signal a bladder fistula. Abdominal pain and distention and fever may indicate intestinal obstruction. Watch for stools from the vagina and an enterovaginal fistula.

♦ Before ileostomy, arrange for a visit by an enterostomal therapist.

♦ After surgery, frequently check the patient’s I.V. and nasogastric tube for proper functioning. Monitor vital signs and fluid intake and output. Watch for wound infection. Provide meticulous stoma care, and teach it to the patient and family. Realize that an ileostomy changes the patient’s body image, so offer reassurance and emotional support.

♦ Stress the need for a severely restricted diet and bed rest, which may be trying, particularly for the young patient. Encourage him to try to reduce tension. If stress is clearly an aggravating factor, refer him for counseling.

♦ Refer the patient to a support group such as the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

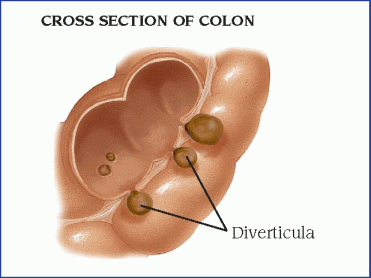

DIVERTICULAR DISEASE

In diverticular disease, bulging pouches (diverticula) in the GI wall push the mucosal lining through the surrounding muscle. Although the most common site for diverticula is in the sigmoid colon, they may develop anywhere, from the proximal end of the pharynx to the anus. Other typical sites include the duodenum, near the pancreatic border or the ampulla of Vater, and the jejunum.

Diverticular disease is common in Western countries, suggesting that a low-fiber diet reduces stool bulk and leads to excessive colonic motility. The consequent increased intraluminal pressure causes herniation of the mucosa.

Diverticular disease is common in Western countries, suggesting that a low-fiber diet reduces stool bulk and leads to excessive colonic motility. The consequent increased intraluminal pressure causes herniation of the mucosa.Diverticular disease of the stomach is rare and is usually a precursor of peptic or neoplastic disease. Diverticular disease of the ileum (Meckel’s diverticulum) is the most common congenital anomaly of the GI tract.

Diverticular disease has two clinical forms:

♦ diverticulosis, in which diverticula are present but don’t cause symptoms

♦ diverticulitis, in which diverticula are inflamed and may cause potentially fatal obstruction, infection, or hemorrhage.

Diverticular disease is most prevalent in men older than age 40 and persons who eat a low-fiber diet. More than one-half of all patients older than age 50 have colonic diverticula.

Diverticular disease is most prevalent in men older than age 40 and persons who eat a low-fiber diet. More than one-half of all patients older than age 50 have colonic diverticula.Causes

♦ Defects in colon wall strength

♦ Diminished colonic motility and increased intraluminal pressure

♦ Low-fiber diet

Pathophysiology

Diverticula probably result from high intraluminal pressure on an area of weakness in the GI wall, where blood vessels enter. Diet may be a contributing factor because insufficient fiber reduces fecal residue, narrows the bowel lumen, and leads to high intra-abdominal pressure during defecation.

In diverticulitis, retained undigested food and bacteria accumulate in the diverticular sac. This hard mass cuts off the blood supply to the thin walls of the sac, making them more susceptible to attack by colonic bacteria. Inflammation follows and may lead to perforation, abscess, peritonitis, obstruction, or hemorrhage. Occasionally, the inflamed colon segment may adhere to the bladder or other organs and cause a fistula. (See Diverticulitis of the colon.)

Signs and symptoms

Typically the patient with diverticulosis is asymptomatic and will remain so unless diverticulitis develops.

Mild diverticulitis

♦ Moderate left-sided lower-abdominal pain secondary to inflammation of diverticula

♦ Low-grade fever from trapping of bacteriarich stool in the diverticula

♦ Leukocytosis from infection secondary to trapping of bacteria-rich stool in the diverticula

Severe diverticulitis

♦ Abdominal rigidity from rupture of the diverticula, abscesses, and peritonitis

♦ Left lower quadrant pain secondary to rupture of the diverticula and subsequent inflammation and infection

♦ High fever, chills, hypotension from sepsis, and shock from the release of fecal material from the rupture site

♦ Microscopic or massive hemorrhage from rupture of diverticulum near a vessel

Chronic diverticulitis

♦ Constipation, ribbon-like stools, intermittent diarrhea, and abdominal distention resulting from intestinal obstruction (possible when fibrosis and adhesions narrow the bowel’s lumen)

♦ Abdominal rigidity and pain, diminishing or absent bowel sounds, nausea, and vomiting secondary to intestinal obstruction

Complications

♦ Abscess

♦ Peritonitis

♦ Intestinal obstruction

♦ Rectal hemorrhage

♦ Septicemia

Diagnosis

♦ Upper GI series confirms or rules out diverticulosis of esophagus and upper bowel.

♦ Barium enema reveals filling of diverticula, which confirms diagnosis.

♦ Sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy help exclude diseases with similiar signs and symptoms.

♦ Biopsy reveals evidence of benign disease, ruling out cancer.

♦ Blood studies show an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate in diverticulitis.

Treatment

♦ Liquid or bland diet, stool softeners, and occasional doses of mineral oil for symptomatic diverticulosis to relieve symptoms, minimize irritation, and lessen the risk of progression to diverticulitis

♦ High-residue diet for treatment of diverticulosis after pain has subsided to help decrease intra-abdominal pressure during defecation

♦ Exercise to increase stool passage rate

♦ An antibiotic to treat infection of the diverticula

♦ An analgesic, such as morphine, to control pain and to relax smooth muscle

♦ An antispasmodic to control muscle spasms

♦ Colon resection with removal of involved segment to correct cases refractory to medical treatment

♦ Temporary colostomy, if necessary, to drain abscesses and rest the colon in diverticulitis accompanied by perforation, peritonitis, obstruction, or fistula

♦ Blood transfusions, if necessary, to treat blood loss from hemorrhage and fluid replacement as needed

Special considerations

Management of uncomplicated diverticulosis chiefly involves thorough patient education about fiber and dietary habits.

♦ Describe diverticula and how they form.

♦ Stress the importance of dietary fiber and the harmful effects of constipation and straining during defecation. Encourage increased intake of foods high in indigestible fiber, including fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grain bread, and wheat or bran cereals. Warn that a highfiber diet may temporarily cause flatulence and discomfort. Advise the patient to relieve constipation with a stool softener or a bulk-forming cathartic. However, caution against taking a bulk-forming cathartic without plenty of water; if swallowed dry, they may absorb enough moisture in the mouth and throat to swell and obstruct the esophagus or trachea.

♦ If the patient with diverticulosis is hospitalized, administer medications as ordered; observe his stools carefully for frequency, color, and consistency; and keep accurate pulse and temperature charts (they may signal developing inflammation or complications).

Management of diverticulitis depends on the severity of symptoms.

♦ In mild disease, give medications as ordered, explain diagnostic tests and preparations for tests, observe stools carefully, and maintain accurate records of temperature, pulse, respirations, intake, and output.

♦ If diverticular bleeding occurs, the patient may require angiography and catheter placement for vasopressin infusion. If so, inspect the insertion site frequently for bleeding, check pedal pulses often, and keep the patient from flexing his legs at the groin.

♦ Watch for vasopressin-induced fluid retention (apprehension, abdominal cramps, convulsions, oliguria, or anuria) and severe hyponatremia (hypotension; rapid, thready pulse; cold, clammy skin; and cyanosis).

After surgery to resect the colon:

♦ Watch for signs of infection.

♦ Provide meticulous wound care as perforation may already have infected the area.

♦ Check drain sites frequently for signs of infection (purulent drainage or foul odor) or fecal drainage.

♦ Change dressings as necessary.

♦ Encourage coughing and deep breathing to prevent atelectasis.

♦ Watch for signs of postoperative bleeding (hypotension and decreased hemoglobin levels and hematocrit).

♦ Record intake and output accurately.

♦ Keep the nasogastric tube patent.

♦ Teach ostomy care as needed.

♦ Arrange for a visit by an enterostomal therapist.

GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

Popularly known as heartburn, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) refers to backflow of gastric or duodenal contents or both into the esophagus and past the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), without associated belching or vomiting. The reflux of gastric contents causes acute epigastric pain, usually after a meal. The pain may radiate to the chest or arms. It commonly occurs in pregnant or obese persons. Lying down after a meal also contributes to reflux.

Causes

♦ Food, alcohol, or cigarettes that lower LES pressure

♦ Hiatal hernia

♦ Increased abdominal pressure, such as with obesity or pregnancy

♦ Medications, such as morphine, diazepam, calcium channel blockers, meperidine, and anticholinergics

♦ Nasogastric intubation for more than 4 days

♦ Weakened esophageal sphincter

Pathophysiology

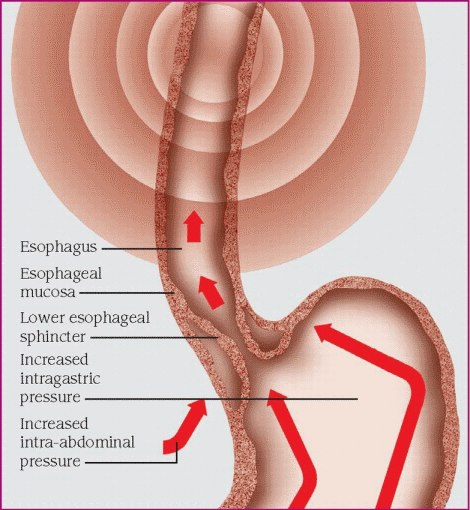

Normally, the LES maintains enough pressure around the lower end of the esophagus to close it and prevent reflux. Typically the sphincter relaxes after each swallow to allow food into the stomach. In GERD, the sphincter doesn’t remain closed (usually due to deficient LES pressure or pressure within the stomach exceeding LES pressure) and the pressure in the stomach pushes the stomach contents into the esophagus. The high acidity of the stomach contents causes pain and irritation when it enters the esophagus. (See How heartburn occurs.)

Signs and symptoms

♦ Burning pain in the epigastric area, possibly radiating to the arms and chest, from the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus causing irritation and esophageal spasm

♦ Pain, usually after a meal or when lying down, secondary to increased abdominal pressure causing reflux

♦ Feeling of fluid accumulation in the throat without a sour or bitter taste due to hypersecretion of saliva

Complications

♦ Reflux esophagitis

♦ Esophageal stricture

♦ Esophageal ulceration

♦ Chronic pulmonary disease from aspiration of gastric contents in the throat

Diagnosis

Diagnostic tests are aimed at determining the underlying cause of GERD:

♦ Esophageal acidity test evaluates the competence of the LES and provides objective measure of reflux.

♦ Acid perfusion test confirms esophagitis and distinguishes it from cardiac disorders.

♦ Esophagoscopy allows visual examination of the lining of the esophagus to reveal the extent of the disease and confirm pathologic changes in mucosa.

♦ Barium swallow identifies hiatal hernia as the cause or esophageal stricture as a complication.

♦ Upper GI series detects hiatal hernia or motility problems.

♦ Esophageal manometry evaluates resting pressure of LES and determines sphincter competence.

Treatment

♦ Diet therapy with frequent, small meals and avoidance of eating before going to bed to reduce abdominal pressure and reduce the incidence of reflux

♦ Positioning—sitting up during and after meals and sleeping with head of bed elevated—to reduce abdominal pressure and prevent reflux

♦ Increased fluid intake to wash gastric contents out of the esophagus

♦ Antacids to neutralize acidic content of the stomach and minimize irritation

♦ A foaming agent, such as Gaviscon, to prevent reflux in patients without damage to the esophagus

♦ A histamine-2 receptor antagonist to inhibit gastric acid secretion

♦ A proton pump inhibitor to reduce gastric acidity

♦ A prokinetic agent to promote gastric emptying and increase LES

♦ A cholinergic to increase LES pressure

♦ Smoking cessation to improve LES pressure (nicotine lowers LES pressure)

♦ Surgery if hiatal hernia is the cause or patient has refractory symptoms

Hormonal fluctuations, mechanical stress, and the effects of certain foods and drugs can decrease lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure. When LES pressure falls and intra-abdominal or intragastric pressure rises, the normally contracted LES relaxes inappropriately and allows reflux of gastric acid or bile secretions into the lower esophagus. There, the reflux irritates and inflames the esophageal mucosa, causing pyrosis (heartburn).

Persistent inflammation can cause LES pressure to decrease even more and may trigger a recurrent cycle of reflux and pyrosis.

|

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved several devices to treat GERD, including:

♦ Bard EndoCinch system, an endoscopic device for chronic GERD, that places stitches in the LES to strengthen it

♦ Stretta system, another endoscopic device for chronic GERD, that uses electrodes to create tiny cuts on the LES; as these cuts heal, they leave scar tissue that strengthens the LES.

Special considerations

Teach the patient what causes reflux, how to avoid reflux with an antireflux regimen (medication, diet, and positional therapy), and what signs and symptoms to watch for and report.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree