Gastrointestinal Disorders

Jeffrey S. Sartin

Key Questions

• What are the common causes of and clinical findings in functional and mechanical bowel obstructions?

• What are the common causes of and clinical findings in gastrointestinal malabsorption disorders?

• What warning signs may indicate cancer of the gastrointestinal tract?

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Copstead/

Alterations in function of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract may have far-reaching consequences in an individual’s life. The ability to take in nutrients, convert them to usable forms for body functions, and dispose of their waste products goes beyond physiologic function and is intimately associated with social and psychological functioning. A person with an alteration in GI function may experience great emotional distress and be unable to participate fully in social activities, which in American society are often centered on food consumption. Certain symptoms that may accompany GI disorders, such as chronic diarrhea and abdominal pain, may severely limit an individual’s ability to maintain employment. It has been estimated that 200,000 people miss work daily because of GI-related problems.1 In addition, GI diseases account for more hospital admissions in the United States than any other category of disease. Because many chronic GI conditions begin in midlife and continue into old age, their prevalence will likely increase as the U.S. population continues to age.

This chapter describes the pathophysiologic processes of the most common disorders of the GI tract and summarizes current treatment for these conditions. Because knowledge about many GI disorders is expanding rapidly, some current research on selected GI conditions is described. Finally, because of the intimate relationship between GI function and the integrity and well-being of the person, a discussion of the psychological and emotional aspects of GI disorders across the life span is included.

Manifestations of Gastrointestinal Tract Disorders

As a basis for discussing individual types of GI disorders, a description of some common manifestations of these disorders and their pathophysiologic mechanisms is presented. Common manifestations include dysphagia, esophageal and abdominal pain, vomiting, intestinal gas, and alterations in bowel patterns.

Dysphagia

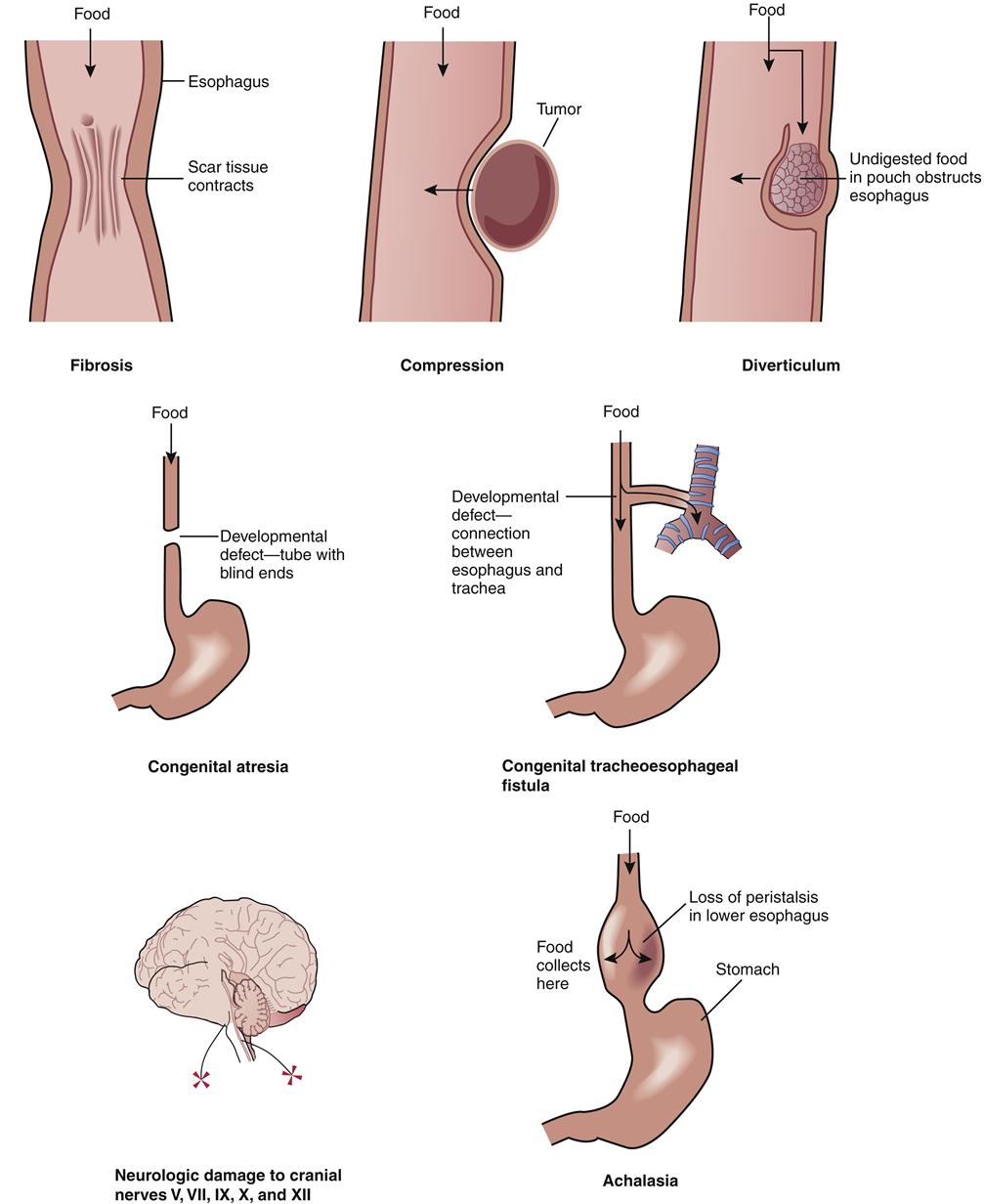

Dysphagia is a subjective difficulty in swallowing (Figure 36-1). It may include the inability to initiate swallowing or the sensation that the swallowed solids or liquids “stick” in the esophagus. In certain disorders, odynophagia, or pain with swallowing, may accompany dysphagia. The physiologic mechanism of normal swallowing is described in Chapter 35.

Categories

The pathophysiologic basis for dysphagia usually falls into three major categories: (1) problems in delivery of the bolus of food or fluid into the esophagus as a result of neuromuscular incoordination; (2) problems in transport of the bolus down the body of the esophagus as a result of altered esophageal peristaltic activity; and (3) problems in bolus entry into the stomach as a result of lower esophageal sphincter (LES) dysfunction or obstructing lesions.2

In the first category of dysphagia, individuals have a decreased ability to accomplish the initial steps of swallowing in an orderly sequence. The normal sequence of contraction of the pharynx, closure of the epiglottis, relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter, and initiation of peristalsis by contraction of the striated muscle in the upper portion of the esophagus is altered, or certain steps in the sequence may be absent. Persons experiencing this type of dysphagia may cough and expel the ingested food or fluids through their mouth and nose or aspirate when they attempt to swallow. These symptoms are usually worse with liquids than with solids in this type of swallowing dysfunction.

The second type of dysphagia may be the result of any disorder, structural or neuromuscular, in which the peristaltic activity of the body of the esophagus is altered. The presence of (1) esophageal diverticula, or outpouchings of one or more layers of the esophageal wall; (2) achalasia, a disorder of esophageal smooth muscle function; or (3) structural disorders such as neoplasms or strictures may interfere with proper peristaltic activity in the esophagus.2,3 This alteration in peristalsis may be simply weak peristaltic activity, aperistalsis (the absence of all peristaltic activity), or disorganized and therefore ineffective peristalsis. With this type of dysphagia the individual may have the sensation that food is “stuck” behind the sternum. Initially, dysphagia may be noted with solid foods; if the underlying pathologic process fosters a worsening of peristaltic ability, the passage of liquids may also become impaired.

The third category of dysphagia, which results from problems of bolus entry into the stomach, is secondary to any condition in which the LES functions improperly or is obstructed by a lesion. Tumors of the mediastinum, lower part of the esophagus, or gastroesophageal junction may invade the myenteric plexus or produce an obstruction at the LES, thus interrupting normal LES function by neural invasion or direct obstruction. In addition, motor disorders resulting from neuromuscular diseases or chronic lower esophageal inflammation from the reflux of acidic gastric contents may limit the ability of the LES to function properly. This type of dysphagia may be manifested as tightness or pain in the substernal area during the swallowing process.

Esophageal Pain

Two types of pain occur in the esophagus: (1) heartburn (also called pyrosis) and (2) pain located in the middle of the chest, which may mimic the pain of angina pectoris. Heartburn is caused by the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus and is a substernal burning sensation that may radiate to the neck or throat. Two common mechanisms contribute to the development of heartburn. First, the highly acidic gastric contents may be a noxious stimulant to sensory afferent nerve endings in the esophageal mucosa. Second, spasm of the esophageal muscle instigated by acid stimulation may produce esophageal pain.

Chest pain other than heartburn may be the result of esophageal distention or powerful esophageal contractions. These stimuli may arise from esophageal obstruction or a condition called diffuse esophageal spasm (DES), in which high-amplitude, simultaneous contractions in the smooth muscle portion of the esophagus alternate with normal peristalsis.1 This type of esophageal pain is similar to that of angina pectoris, particularly in its pattern of radiation into the neck, shoulder, arm, and jaw. Odynophagia may accompany diffuse esophageal spasm and can be indistinguishable from esophageal chest pain, except that it is triggered specifically by swallowing.

Infections of the esophagus attributable to herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, or Candida species occur in immunocompromised patients. Patients with infectious esophagitis may experience a dull, aching chest pain. Swallowing generally worsens the sensation of heartburn or chest pain.

Abdominal Pain

Pain in the abdominal region may be the first sign of a disorder of the GI tract and is often an important impetus for seeking medical care. Although abdominal pain may result from GI tract disorders, it may also be the result of reproductive, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, or vascular disorders, as well as toxins or drug use. Abdominal pain is usually categorized into three types, which may manifest separately or in combination: (1) Visceral pain develops from stretching or distending an abdominal organ or from inflammation. The pain is diffuse and poorly localized and has a gnawing, burning, or cramping quality. (2) Somatic pain arises from injury to the abdominal wall, the parietal peritoneum, the root of the mesentery, or the diaphragm. In contrast to visceral pain, it is sharper, more intense, and generally well localized to the area of irritation. (3) Referred pain is felt at a location distant from the source of the pain but in the same dermatome or neurosegment. Referred pain is usually sharp and well localized and may be felt in the skin or deeper tissues.

Abdominal pain may be acute with instantaneous onset, such as pain caused by a perforated ulcer or a ruptured internal organ. A more gradual development of abdominal pain may accompany such chronic states as diverticulitis or ulcerative colitis (UC). Abdominal pain seldom occurs as a solitary manifestation of GI disorders; it is usually accompanied by other manifestations such as vomiting or alteration in bowel patterns to a variable degree.

Vomiting

Vomiting is the forceful expulsion of gastric contents through the mouth. Usually accompanied by a feeling of nausea, vomiting results from a coordinated sequence of abdominal muscle contractions and reverse esophageal peristalsis. Although vomiting is a common sign of GI disorders, it may also occur with metabolic, endocrine, vestibular (inner ear), and cardiac disorders, as well as with infection and fluid and electrolyte imbalances. It is also associated with such nonpathologic causes as pharmacologic agents, surgery, and the first trimester of pregnancy.

Vomiting associated with GI disorders may be the result of alterations in the integrity of the GI tract wall, such as gastroenteritis, or alterations in the motility of the GI tract, such as intestinal obstruction. The characteristics of the vomitus and the presence of blood or fecal matter may suggest the nature of the GI disorder and the level of the GI tract at which the disorder is located.

Intestinal Gas

Gas normally occurs in the GI tract and is the result of the swallowing of air, bacterial and digestive action on intestinal contents, diffusion from the blood, and the neutralization of acids by bicarbonate within the upper GI tract. The manifestations of excess intestinal gas may include excessive belching, distention of the abdomen, and excessive flatus. These manifestations may occur singly or in combination and may stem from a variety of causes. Belching is a normal phenomenon caused by the eructation of swallowed air but may also be the result of a motility disorder or gastric outlet obstruction. Abdominal distention may be due to failure to adequately digest a particular nutrient, such as the carbohydrate lactose. In the absence of adequate lactase (the digestive enzyme that breaks down lactose into glucose and galactose in the intestine), lactose undergoes bacterial fermentation, which results in gas production in the intestinal lumen. In some individuals, abdominal distention from excess gas may result from a defect in intestinal motility in which the intestinal contents are not propelled in a regular fashion, rather than from the production of too much gas. Excessive flatus may have causes similar to those of abdominal distention. Usually it is the result of increased amounts of gas produced by the action of bacteria on nutritional substrates that are particularly gas-producing, such as certain vegetables and legumes. Some individuals are particularly sensitive to the flatulent effects of beans, for instance.

Alterations in Bowel Patterns

Both constipation and diarrhea are difficult to define with precision, as a wide variation in bowel patterns can be found in different individuals. In addition, cultural and family socialization may play a role in the way in which an individual perceives bowel patterns. Alterations in bowel patterns may be the result of a change in GI tract motility or may be a component of a functional GI disorder such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Constipation

Constipation may be defined as small, infrequent, or difficult bowel movements.2 Authorities have agreed on a norm of fewer than three stools per week as a guideline for defining constipation.1 Dietary factors, particularly a diet low in fiber, have been shown to contribute to constipation. The presence of cellulose, the carbohydrate component of dietary fiber that is indigestible in the human intestine, may be effective in promoting regular peristaltic movement in the GI tract by forming bulk within the intestinal lumen to stimulate propulsion. In addition, because exercise stimulates intestinal peristalsis, a lack of exercise has been implicated in the development of constipation. In elderly persons the slowed rate of peristalsis that occurs with the aging process coupled with a decreased level of physical activity may promote chronic constipation. These factors may eventually contribute to the development of fecal impaction, a condition in which a firm, immovable mass of stool becomes stationary in the lower GI tract. Constipation may also be the result of pathologic conditions, including processes that alter the motility of the GI tract (such as intestinal obstruction) or processes that alter the integrity of the GI tract wall (such as diverticulitis).

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is defined as an increase in the frequency and fluidity of bowel movements and is often a primary sign of GI tract disorders. Although stool weight in excess of 200 g in 24 hours is an easily obtainable, objective definition of diarrhea,3 most persons consider increased liquidity as the primary determinant. Diarrhea may be present as an acute or chronic manifestation. Acute diarrhea may be the result of an acute infection, emotional stress, or leakage of liquid stool around impacted feces. Chronic diarrhea is usually defined as symptoms lasting longer than 4 weeks and may be the result of a chronic GI tract infection (often associated with immune system compromise), alterations in the motility or integrity of the GI tract, malabsorption disorders, or certain endocrine disorders. Diarrhea that occurs on an episodic basis may be related to a food allergy or may be due to the ingestion of irritants to the GI tract, such as caffeine. Diarrhea in children frequently results from infection, although malabsorption disorders, anatomic defects, and allergy issues may also be causative factors.4

Pathophysiologic mechanisms

Four major pathophysiologic mechanisms have been identified in the development of diarrhea: (1) In osmotic diarrhea, increased amounts of poorly absorbable, osmotically active solutes such as a carbohydrate or magnesium sulfate cause sodium and water influx into the bowel lumen, resulting in diarrhea. (2) In secretory diarrhea, a pathophysiologic event such as the presence of a bacterial toxin causes enhanced secretion of chloride ion and water in the small intestine by simultaneously stimulating active secretion and inhibiting resorption. Diarrhea of 1 L or more per day may result from this inappropriate secretion of fluid across the intestinal mucosa.2 Causes of secretory diarrhea include enterotoxins produced by such organisms as Vibrio cholerae and Staphylococcus aureus. (3) Exudative diarrhea is the result of exudation of mucus, blood, and protein from sites of active inflammation into the bowel lumen. This creates an increased osmotic load and a subsequent shift of water across the epithelium. In addition, if a large surface area of the bowel has an alteration in its integrity, intestinal absorption will be severely impaired, further compounding the diarrhea produced. Diarrhea associated with Crohn disease and UC may be the result of this exudative process.2 (4) Diarrhea related to motility disturbances is a result of the decreased contact time of chyme with the absorptive surfaces of the intestinal lumen. If inadequate absorption takes place in the small intestine, large amounts of fluid will be delivered to the colon and may overwhelm the absorptive capability of the colon and cause diarrhea. In addition, if the fatty acids and bile salts present in chyme have not been adequately absorbed in the small intestine, they may induce a secretory diarrhea once they reach the colon, further compounding the process of diarrhea formation. Diarrhea associated with postgastrectomy dumping syndrome and IBS are examples of this type of diarrhea.

Disorders of the Mouth and Esophagus

The mouth and the esophagus are the portals of entry for nutrients into the GI tract. An impairment in the proper functioning of these structures may have a profound effect on the ability of the individual to ingest adequate nutrients and begin the initial steps of the digestive process. Although disorders of the mouth and esophagus may not be acute, life-threatening emergencies, they may have severe long-term consequences for the well-being of the individual experiencing them.

Oral Infections

Stomatitis

Etiology

Stomatitis is defined as an ulcerative inflammation of the oral mucosa that may extend to the buccal mucosa, lips, and palate. Among its many causes are pathogenic organisms, including bacteria and viruses; mechanical trauma; exposure to such irritants as alcohol, tobacco, and other chemical substances; certain medications, particularly chemotherapeutic agents; radiation therapy; and nutritional deficiencies, especially vitamin deficiencies. Stomatitis is a central manifestation of several autoimmune disorders, including Reiter syndrome and Behçet syndrome.5 Stomatitis may also be idiopathic; that is, it has no identifiable cause.

One of the most commonly encountered types of stomatitis is acute herpetic stomatitis, also called herpetic gingivostomatitis, or more colloquially cold sores. It is caused by infection with herpes simplex virus (HSV), which has an affinity for the skin and nervous system. This type of stomatitis is commonly acquired by children between the ages of 1 and 3 years, although it may occur at any age. In primary infection, a brief period of prodromal tingling and itching may be present along with fever and pharyngitis. Vesicles may erupt on any part of the oral mucosa, particularly the tongue, gums, and cheeks. Vesicles form on an erythematous base, eventually rupture, and leave a painful ulcer. Once herpes simplex virus is acquired, it remains latent in the dorsal ganglia of the spinal cord and may be reactivated by physical or emotional stressors.

Treatment

The pharmacologic therapy used for stomatitis depends on its cause. The antiviral drugs acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir have been approved for treating acute herpetic stomatitis. Unfortunately, in a significant number of cases stomatitis is idiopathic or not amenable to specific therapy (e.g., stomatitis attributable to chemotherapy). In all types of stomatitis, measures designed to provide adequate oral hygiene and increase comfort in the oral cavity will be helpful in preventing decreased nutritional intake during the period of inflammation and assist in promoting the healing process. Topical mucosal barriers and corticosteroids may be of some benefit (e.g., triamcinolone [Kenalog] in Orabase)5 whereas pentoxyphylline, colchicine, dapsone, and thalidomide have been used for recalcitrant cases of idiopathic stomatitis.6

Esophageal Disorders

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the backflow of gastric contents into the esophagus through the LES. GERD may or may not produce symptoms.

Pathogenesis

The production of GERD is a multifactorial process. Any condition or agent that alters the closure strength and efficacy of the LES or increases intraabdominal pressure may predispose an individual to GERD. For example, the closure strength of the LES may be adversely affected by the intake of fatty foods, caffeine, and alcohol; cigarette smoking; sleep position; or obesity. In addition, pharmacologic agents such as progesterone-containing medications (e.g., birth control pills), narcotics, benzodiazepines, calcium channel blockers, and theophylline may decrease the pressure of the LES. Pregnancy increases the risk of reflux both by increasing intraabdominal pressure and by affecting hormonal mechanisms. Certain anatomic features, especially hiatal hernia, have been associated with GERD. The extent and severity of damage to the esophagus from GERD reflect the frequency and duration of exposure to refluxed material, as well as the volume and acidity of the gastric juices being refluxed.2,3 The role of Helicobacter pylori, a cause of gastric and duodenal ulceration, in GERD is poorly understood and controversial.7

Clinical manifestations

The most common manifestations of GERD are heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain, and dysphagia. These symptoms are related to reflux esophagitis, which is esophageal inflammation caused by the highly acidic refluxed material. Complications of persistent GERD include esophageal strictures, Barrett esophagus (see Complications section), and pulmonary symptoms related to reflux esophagitis, such as cough, asthma, and laryngitis.

Treatment

Appropriate therapy is directed to increasing LES pressure, enhancing esophageal clearance, improving gastric emptying, and suppressing gastric acidity. Dietary and behavioral changes, such as avoiding tobacco and aggravating food and drink, are indicated for all patients, whereas over-the-counter antacids and histamine (H2)-blocking medications may be effective for occasional GERD. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the mainstays of treatment for chronic GERD and have proven very successful in halting and even reversing the changes of chronic GERD.8 If reflux esophagitis has progressed in severity, tissue damage, including ulceration, fibrotic scarring, and strictures, may be present in the distal third of the esophagus. Upper GI endoscopy is indicated for patients with ongoing symptoms, and some patients with stricture may require endoscopic dilatation. Surgical intervention, such as thoracoscopic Nissan fundoplication, may be helpful for intractable GERD.9

Complications

Barrett esophagus is a complication of chronic GERD and involves columnar tissue replacing the normal squamous epithelium of the distal esophagus. It carries a significant risk for esophageal cancer, and patients with Barrett esophagus should undergo regular endoscopic screening for cancer, along with pharmacologic control of their reflux.10 For patients with documented dysplastic changes, endoscopic eradication therapy is a relatively low-morbidity option for treatment.11

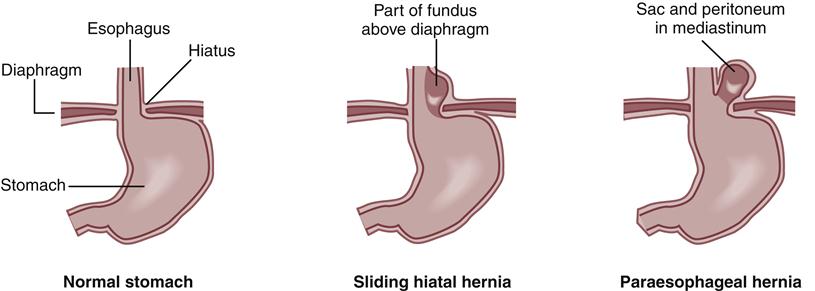

Hiatal Hernia

A hiatal hernia is a defect in the diaphragm that allows a portion of the stomach to pass through the diaphragmatic opening into the thorax. Two types of hiatal hernia are commonly recognized: (1) a sliding hernia, in which both a portion of the stomach and the gastroesophageal junction slip up into the thorax so that the gastroesophageal junction is above the diaphragmatic opening; and (2) a paraesophageal hernia, in which a part of the greater curvature of the stomach rolls through the diaphragmatic defect (Figure 36-2). “Mixed” hiatal hernias with features of both of these types may also occur. Sliding hernias are 3 to 10 times more common than paraesophageal and mixed hernias combined. The incidence of hiatal hernia increases with age and occurs more often in women than in men.

Etiology

Although the cause of the anatomic deformity leading to hiatal hernia is not well understood, certain conditions seem to predispose to loosening of the muscular band around the esophageal and diaphragmatic junction. Conditions in which intraabdominal pressure increases, such as ascites, pregnancy, obesity, and chronic straining or coughing, have been associated with the development of hiatal hernia.

Clinical manifestations and treatment

Individuals with hiatal hernia are predisposed to GERD and may experience symptoms such as heartburn, chest pain, and dysphagia. Ulcerations can develop along the mucosal surface of the stomach as it slides through the diaphragmatic opening, so-called Cameron ulcers. This is a fairly uncommon cause of chronic upper GI blood loss.12 A potentially life-threatening situation can develop if a large portion of the stomach becomes caught above the diaphragm and is incarcerated, although this is extremely rare. Medical therapy for hiatal hernia is the same as that for GERD, detailed previously. Indications for surgery include acute incarceration or intractable reflux.

Mallory-Weiss Syndrome

Etiology

Mallory-Weiss syndrome is bleeding caused by a tear in the mucosa or submucosa of the cardia or lower portion of the esophagus. The tear is usually longitudinal and is primarily caused by forceful or prolonged vomiting in which the upper esophageal sphincter fails to relax during the vomiting process. Approximately 75% of individuals with Mallory-Weiss syndrome are men with a history of excessive ingestion of alcohol or salicylates.2 Other factors and conditions that may contribute to the development of esophageal tearing in Mallory-Weiss syndrome are coughing, straining during bowel movements, trauma, hiatal hernia, esophagitis, and gastritis. Use of polyethylene glycol as a preparation for colonoscopy has also been associated with Mallory-Weiss tears.13

Clinical manifestations and treatment

Manifestations of Mallory-Weiss syndrome include vomiting of blood and passing of large amounts of blood rectally after an episode of forceful vomiting. Epigastric or back pain may also be present. Bleeding may range in severity from mild to massive. It is often profuse when the tear is near the cardia of the stomach and may proceed to fatal shock in this circumstance. Identification is made by endoscopic examination during an episode of acute upper GI bleeding. The majority of patients require at least one blood transfusion, but in most cases bleeding stops spontaneously.14–19 Control of active bleeding may be achieved through endoscopic multipolar electric coagulation or similar techniques, epinephrine injection, or through interventional radiologic procedures (e.g., vasopressin infusion, Gelfoam embolization).20 In selected cases, surgical intervention may be necessary.

Esophageal Varices

Esophageal varices represent a complication of portal hypertension, which in Western society is generally the result of cirrhosis attributable to alcoholism or viral hepatitis. In developing tropical countries, chronic infection with the Schistosoma species of liver flukes is a major cause of portal hypertension, along with cirrhosis attributable to chronic hepatitis B infection. Varices will affect more than half of cirrhotic patients, and approximately 30% of these patients experience an episode of variceal hemorrhage within 2 years of the diagnosis of varices.21 The diagnosis and management of varices are discussed in detail in Chapter 38.

Alterations in the Integrity of the Gastrointestinal Tract Wall

Alterations in the integrity of the GI tract may occur at any location along the approximately 30 feet of its length, resulting from infection, an inflammatory process, or weakness of the intestinal wall. Such alterations may present as an acute, life-threatening situation or as a chronic, disabling condition. When the integrity of the GI tract wall is compromised, the ability to perform digestive and absorptive functions may also be compromised because the surface area or motility (or both) is altered.

Inflammation of the Stomach and Intestines

Gastritis

Etiology

Gastritis is defined as an inflammation of the stomach lining. Acute inflammation of the stomach lining may occur after the ingestion of alcohol, aspirin, or irritating substances, as well as be caused by viral, bacterial, or autoimmune illnesses. (Some experts prefer use of the term gastropathy for toxic gastric inflammation, with gastritis defined as gastric inflammation attributable to infection or autoimmune disorders.17) In Western countries, overuse of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and overindulgence in alcohol and tobacco are preeminent causes of acute gastritis.

Pathogenesis

Chronic gastritis is currently the focus of extensive research. The factors promoting chronic gastritis have always been poorly understood. However, in 1983 identification of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori proved to be a landmark event.18 Since that time, H. pylori has generated worldwide attention for its role in the promotion of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease (PUD), and gastric carcinoma and lymphoma. Circumstantial evidence suggests that the mode of transmission of H. pylori is primarily person to person.19 Some studies suggest a fecal-oral route, with the possibility of a reservoir in water sources.

It is now known that H. pylori causes chronic, superficial gastritis in virtually all infected persons.2 Once established in the gastric mucosa, H. pylori establishes a destructive pattern of persistent inflammation. This persistent inflammation may resolve spontaneously, with clearance of the organism over time, leading to a decreased prevalence of H. pylori infection among older individuals. Consequences of H. pylori gastritis include PUD (discussed in a later section), atrophic gastritis, gastric adenocarcinoma, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. The diagnosis and management of H. pylori infection will be discussed below.

Clinical manifestations

Although gastritis may be asymptomatic, manifestations of acute gastritis include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and postprandial discomfort. Occasionally, hematemesis may occur in response to damage to the gastric epithelial mucosa. These manifestations usually disappear when the causative agent is removed, and the gastric epithelium undergoes a process of renewal after sloughing off the layer of damaged cells.

Gastroenteritis

Etiology

Gastroenteritis refers to inflammation of the stomach and small intestine, and may occur on an acute or chronic basis. Chronic gastroenteritis is usually the result of another GI disorder, such as Crohn disease, and is discussed in a later section. Acute gastroenteritis is the result of direct infection of the GI tract lining by a pathogenic organism such as the Norwalk virus, or it can occur from ingestion of preformed bacterial toxins (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus) or bacteria that produce toxins (e.g., Clostridium perfringens). Acute gastroenteritis may also be caused by an imbalance in the normal bacterial flora of the GI tract precipitated by the introduction of an unusual bacterial strain, as may occur during travel.

Clinical manifestations and treatment

Acute gastroenteritis in adults is usually a self-limiting, nonfatal disease with manifestations of diarrhea, abdominal discomfort and pain, nausea, and vomiting. An elevated temperature and malaise may also be present. The manifestations vary according to the type of causative pathologic organism and the region of the GI tract affected. Many pathogenic organisms induce a severe secretory type of diarrhea (see the earlier discussion on the pathophysiologic mechanism of secretory diarrhea). In children and the elderly, fluid losses from diarrhea and vomiting can have serious consequences and may be life-threatening, particularly in underdeveloped countries. Supportive treatment designed to provide fluid and electrolyte replacement may thus be required for many patients experiencing severe acute gastroenteritis.

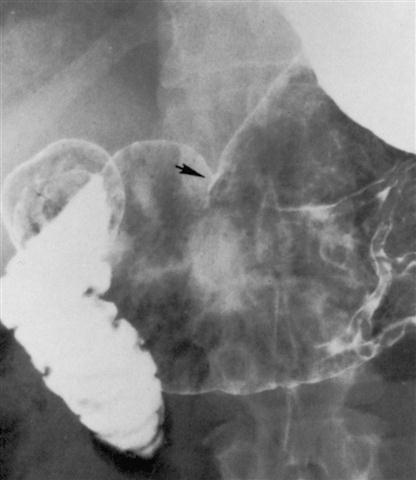

Peptic Ulcer Disease

The term peptic ulcer disease (PUD) refers to disorders of the upper GI tract caused by the action of hydrochloric acid and pepsin. These disorders may include injury to the mucosa of the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum and may range from a slight mucosal injury to severe ulceration (Figures 36-3 and 36-4). Peptic ulcer disease seems to be the result of an increase in factors that tend to injure the mucosa relative to factors that tend to protect it. The presence of an intact gastric mucosal barrier and the ability of the mucosa to renew its epithelium serve to protect it against injury. On the other hand, the presence of hydrochloric acid, which potentiates the actions of pepsin and other injurious substances such as aspirin and NSAIDs, will promote injury to the mucosa.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree