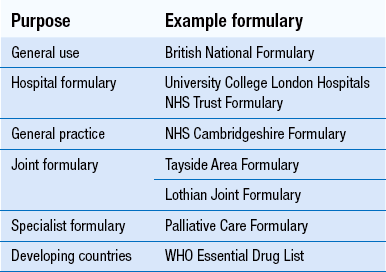

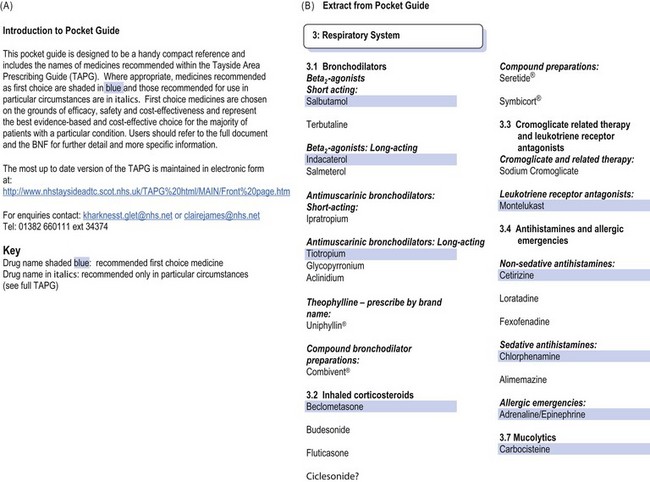

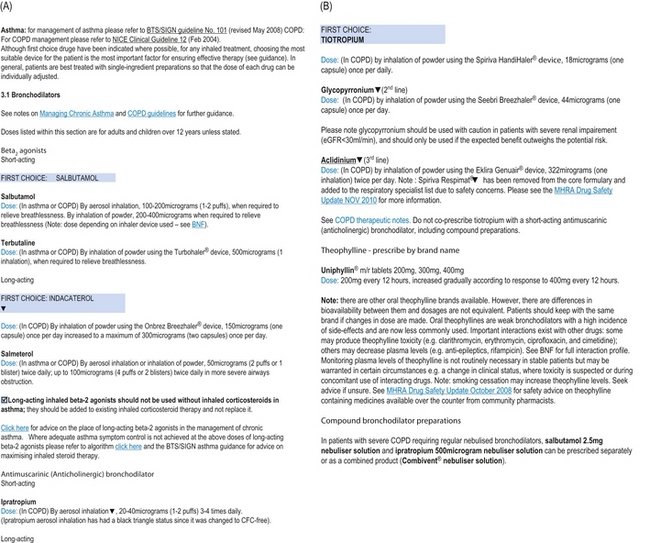

23 Formularies were originally compilations of medicinal preparations, with the formulae for compounding them. The modern definition of a formulary is a list of drugs which are recommended or approved for use by a group of practitioners. It is compiled by members of the group and is regularly revised. Drugs are usually selected for inclusion on the basis of efficacy, safety, patient acceptability and cost. Drugs listed in a formulary should be available for use. Information on dosage, indications, side-effects, contraindications, formulations and costs may also be included. An introduction, giving information on how the drugs were selected, by whom and how to use the formulary, is usually provided. Local formularies, or lists of recommended drugs, have been widely used in hospitals and in primary care throughout the UK for many years. Some are designed for small groups, such as one general medical practice; some are for all prescribers within a hospital; others may be intended for all prescribers within a large geographical area. The latter are often joint formularies, compiled by and intended for use by prescribers in both primary and secondary care. An NHS-funded minor ailments service delivered by community pharmacy is also widespread in the UK (see Ch. 21), which provides selected medicines free of charge to certain patients, requiring the development of formularies from which pharmacists can supply the recommended products. All of these are local formularies and are usually developed and maintained by an Area Drug and Therapeutics Committee (ADTC). These committees involve pharmacists, hospital doctors, general practitioners and nurses who practise within a locality, and often also include management, public health and financial expertise. Worldwide, formularies as a concept are promoted by the WHO. The essential medicines list, which is recommended as necessary for basic health care in developing countries, is similar to a formulary. Any country can modify this list to meet its own particular needs and arrive at a ‘national formulary’. The basis of any list is that the drugs it contains are of proven therapeutic efficacy, acceptable safety and satisfy the health needs of the populations they serve. Some examples of formularies are given in Table 23.1. Prescribing, which is based on the four important factors of efficacy, safety, patient acceptability and cost, should be rational (see Ch. 20). While many drugs may be available to treat any particular condition, the process of selecting the most appropriate one for any individual patient should take account of all these factors, plus other patient factors, such as concurrent diseases, drugs, previous exposure and outcomes. The four factors can also be applied to selection of drugs to treat populations of patients and it is for this situation that formularies are developed. Providing drug selection is based on good quality evidence of efficacy, toxicity and cost-effectiveness, formularies then assist in making decisions regarding individual patients. Formularies often provide information on the cost of products to help users to become cost conscious. Local formularies usually include only a small proportion of the drugs listed in an extensive national formulary, such as the BNF. In general, only between 300 and 500 drugs are required to manage the majority of common conditions. If prescribers only use the drugs included in a local formulary, the range stocked by pharmacies can decrease, which reduces unnecessary outlay. Using a restricted range of drugs may allow pharmacists to buy these in bulk, further reducing costs. Formularies also encourage generic prescribing which may reduce costs even further. If fewer products are stocked, monitoring of expiry dates becomes easier and cash flow may improve. Any money saved by using a formulary may be used to benefit patients in other ways. For example, reducing the prescribing of drugs which have little evidence of therapeutic benefit, such as peripheral vasodilators, could enable more to be spent on lipid-lowering drugs. Formularies usually recommend using the most cost-effective option where there are a number of alternatives. In addition, as safety is also a key factor in drug selection, formularies may contribute to reducing the incidence of ADRs, which often carry a high cost. The formulary should start with an introduction, giving the names of those who have compiled it, stating who is expected to use it and explaining its format. An example is shown in Figure 23.1A, from the NHS Tayside Area Formulary. It is important to state whether all the drugs included are recommended for all users, and if not, how different recommendations can be distinguished. The BNF, for example, lists drugs the Joint Formulary Committee considers less suitable for prescribing, in small type. The examples in Figures 23.1 and 23.2 illustrate how the recommended first choice drugs are highlighted. Local formularies may choose to place restrictions on some drugs, for use by specialists only, for certain indications only or in certain locations only. These drugs should also be easily distinguishable from the others in the formulary; in Figure 23.1A, these are in italic. A list of contents and an index should be included to make the formulary easy to use. Figure 23.1 Introduction and formulary recommendations for bronchodilators, illustrating presentation as a Pocket Guide. (Adapted from the TAPG Pocket Guide 2010, ©NHS Tayside Area Drug and Therapeutics Committee, with permission.) Figure 23.2 Formulary recommendations for bronchodilators, illustrating presentation as a detailed prescribing guide. (Reproduced with permission from NHS Tayside Area Drug and Therapeutics Committee. Extraction date: 11 February 2013.) http://www.nhstaysideadtc.scot.nhs.uk/TAPG%20html/MAIN/Front%20page.htm Paper formats can be portable, making for ease of use in any clinical setting, from the hospital bedside to the patient’s home. However, they are expensive to produce and still require regular updating. The size of the document is an important consideration. Ideally, it should be no bigger than pocket-sized, perhaps compatible in size with the BNF, to make it easy to use the two together. A simple list of formulary drugs is a useful option, such as that illustrated in Figure 23.1B, produced by NHS Tayside ADTC. This can be supplemented by a larger document in either paper or electronic form. If the formulary is only available as a large paper document which cannot be carried around, it is much less likely to be available when needed, which may mean its recommendations are ignored. Colour and a durable cover to withstand regular use can both add further to the appearance of a paper formulary, but also increase its cost. Whatever format is used, the formulary should be easy to use, to encourage prescribers to refer to it when necessary. This will be helped by a contents list, which for a paper version means the pages have to be numbered. Arranging the drugs in the same order as the BNF will also help to make the formulary easier to use, for prescribers who already use the BNF. Using different typefaces and print size can make a formulary easier to use. Highlighting the drug names can be useful, as often the name of the recommended drug may be all that someone is seeking (see Fig. 23.1B).

Formularies in pharmacy practice

Different types of formularies

Benefits of formularies

Rational prescribing

Cost-effective prescribing

Formulary development

Content

Presentation of a formulary

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree