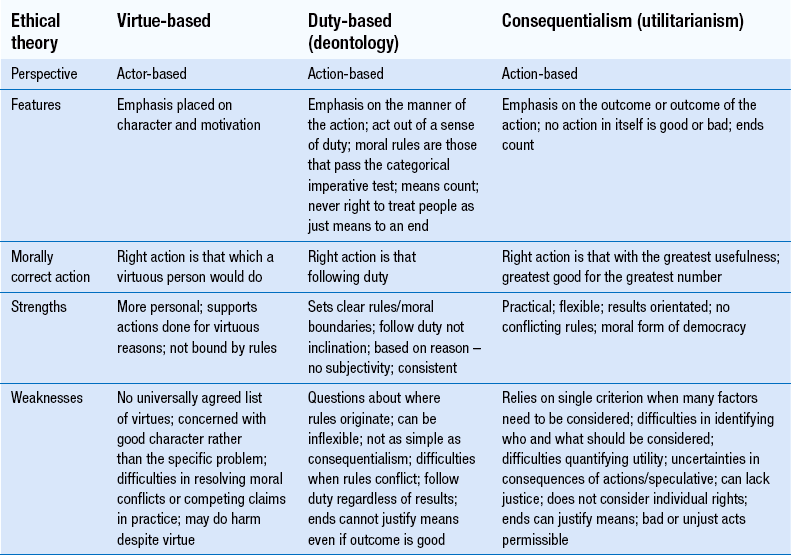

7 The aim of this chapter is to introduce the concept of ethics, briefly explain ethical theories and principles and relate these to issues of relevance in pharmacy and healthcare practice. Ethical theories provide a framework within which the acceptability of actions and the morality of judgements can be assessed. Absolutist theories rest on the assumption that there is an absolute right or wrong. Relativistic or reason-based theories rest on the assumption that right or wrong can depend purely on what any society, group or individual believes. Normative theories are distinguished by the way in which they provide ethical guidance: These are summarized in Table 7.1. Aristotle (384–322 bc) was concerned with what makes a good person rather than what makes a good action. He believed that being moral involved rationally applying good sense to find the middle way between one extreme and another, for example courage is the mean between cowardice and rashness (Box 7.1). This second version has been very influential in medical ethics, as it can be translated as saying it is necessary to treat people as autonomous agents capable of making their own decisions. The concept of autonomy and respecting an autonomous decision demonstrates respect for the person as an ‘end in itself’. WD Ross (1877–1971) recognized that a number of obligations present themselves in practical situations and that we must weigh up the various options available when deciding which course of action is morally correct (Hawley 2007). Ross distinguished duties as prima facie or ‘actual’ duties. A prima facie duty is one that is always to be performed unless it conflicts with an equal or stronger duty. The stronger duty becomes an actual duty that must be carried out for the action to be morally correct. The prima facie duty to keep a promise, for example, could be over-ridden if it was not in a person’s best interests. Ross identified seven prima facie duties (see Box 7.2). These are supplemented with four ‘rules’: Autonomy encompasses the capacity to think, decide and act freely and independently. Respect for autonomy flows from the recognition that all rational beings have unconditional worth, and each has the capacity to determine his or her own destiny. People should be seen as ends in themselves and not treated simply as means to the ends of others. Three types of autonomy have been suggested:

Ethics – the theory

The major ethical theories and principles applied to decision-making in health care

The major ethical theories and principles applied to decision-making in health care

The key limitations of each ethical theory

The key limitations of each ethical theory

The distinction between morals, ethics and law

The distinction between morals, ethics and law

Ethical decision-making frameworks

Ethical decision-making frameworks

Introduction

Morals, values and ethics

Descriptive ethics simply describes the way things are – how people actually behave

Descriptive ethics simply describes the way things are – how people actually behave

Meta-ethics is concerned with analysis of the language people use when they discuss a moral issue, e.g. the meaning of the words ‘right’ and ‘wrong’

Meta-ethics is concerned with analysis of the language people use when they discuss a moral issue, e.g. the meaning of the words ‘right’ and ‘wrong’

Normative ethics is concerned with how things ought to be, how people should behave and how people justify decisions when faced with situations of moral choice. It attempts to generate the norms or standards of the right action.

Normative ethics is concerned with how things ought to be, how people should behave and how people justify decisions when faced with situations of moral choice. It attempts to generate the norms or standards of the right action.

Ethical theories

Normative theories of ethics

Virtue ethics locate the highest moral value in the development of persons

Virtue ethics locate the highest moral value in the development of persons

Consequentialist (or utilitarian) theories evaluate actions by reference to their outcomes

Consequentialist (or utilitarian) theories evaluate actions by reference to their outcomes

Deontological theories hold that actions are intrinsically right or wrong.

Deontological theories hold that actions are intrinsically right or wrong.

Virtue ethics

Deontology

Kantianism

First version: ‘Act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law’

First version: ‘Act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law’

Second version: ‘Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end’

Second version: ‘Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end’

Ross’s prima facie duties

Principlism and the four ethical principles

Autonomy

Autonomy of thought: thinking for oneself, making decisions, believing things, making moral assessments

Autonomy of thought: thinking for oneself, making decisions, believing things, making moral assessments

Autonomy of will (intention): freedom to do things on the basis of one’s deliberations

Autonomy of will (intention): freedom to do things on the basis of one’s deliberations

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Ethics – the theory

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue