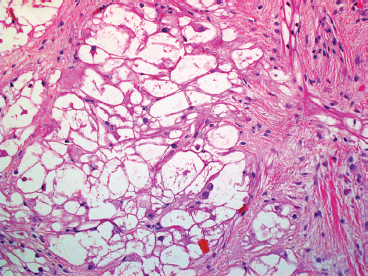

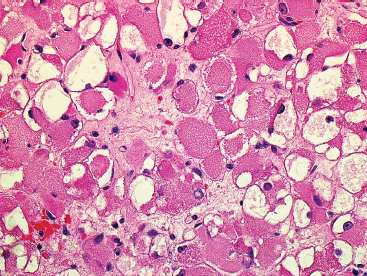

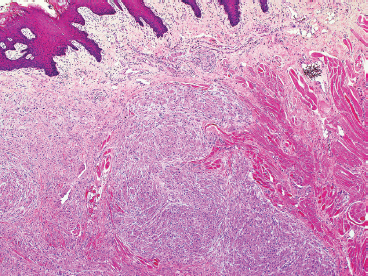

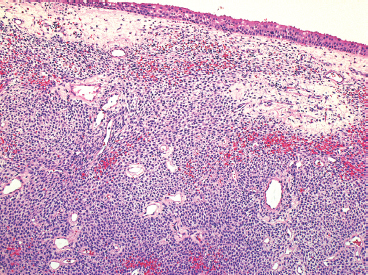

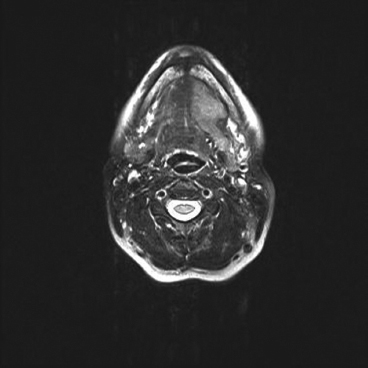

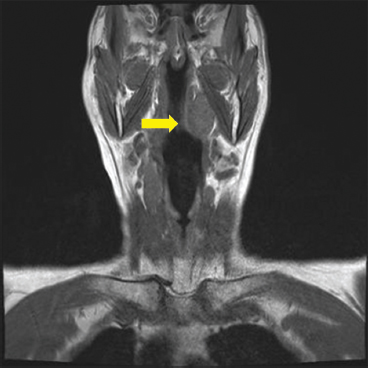

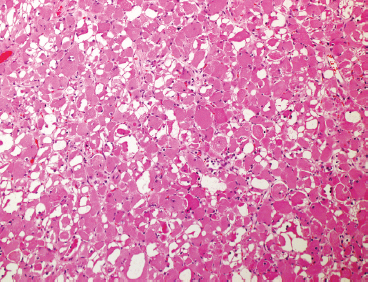

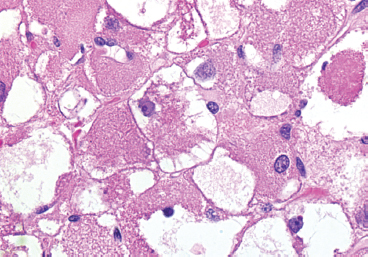

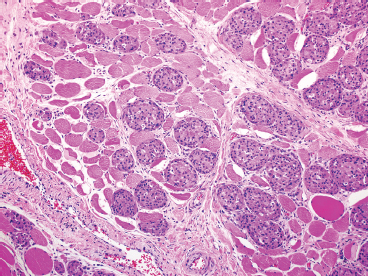

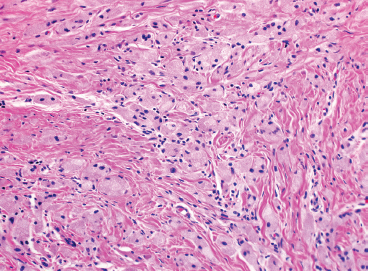

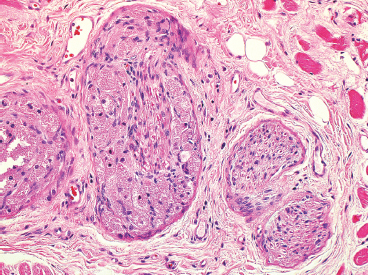

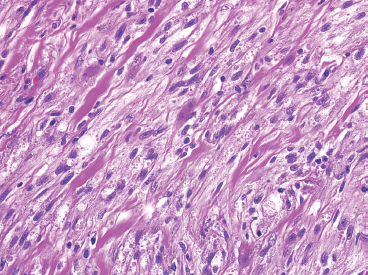

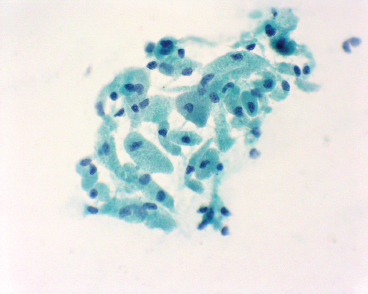

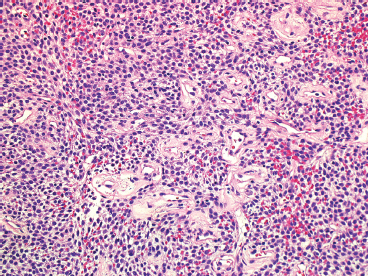

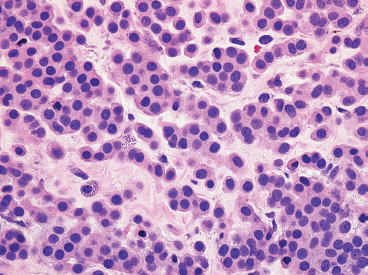

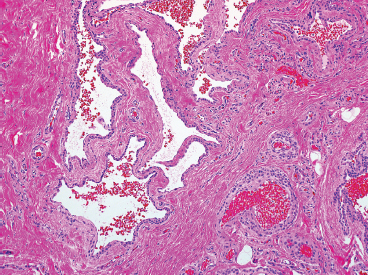

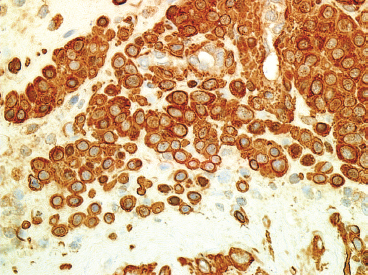

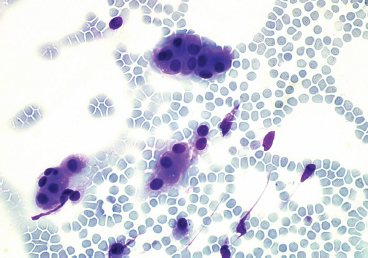

EPITHELIOID SOFT TISSUE TUMORS 8.4 Neoplasms With Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Differentiation (PEComa) 8.5 Myoepithelial Tumors of Soft Tissue 8.8 Alveolar Soft Part Sarcoma Rhabdomyoma represents a benign tumor of skeletal muscle differentiation. Interestingly, rhabdomyomas are relatively rare, thought to represent about 2% of all tumors of skeletal muscle differentiation (rhabdomyosarcoma being far more common). Clinically, rhabdomyomas can be separated into cardiac and noncardiac types. Cardiac forms of rhabdomyoma occur almost exclusively in infants and young children (Figure 8.1.1). A majority of patients with cardiac rhabdomyoma will have tuberous sclerosis, a multiorgan genetic syndrome characterized by tumors of the brain, kidney, and lung, as well as the heart. For classification purposes, noncardiac rhabdomyomas are separated into adult and fetal forms. In addition, there is a rare form of rhabdomyoma that occurs in the genital tract that is considered a separate entity. The majority of adult forms of rhabdomyosarcoma occur in the head and neck region (Figures 8.1.2 and 8.1.3). Favored sites include the parapharyngeal soft tissues, larynx, mouth, and neck. About 20% of patents will have more than one (multifocal) rhabdomyoma. Most patients are adults, and the median age of presentation is 60 years. There is a marked male predominance with a male-to-female ratio of 3 to 1. Rhabdomyomas are slow-growing lesions. Symptoms are often related to compression effects instead of pain. Patients can present with hoarseness as well as difficulty breathing or swallowing. Adult rhabdomyomas are typically well circumscribed and can be pedunculated or polypoid in appearance. They are unencapsulated, lobular lesions with a very characteristic histopathologic appearance. The cells of adult rhabdomyoma are large and contain abundant cytoplasm (Figure 8.1.4). They have round, oval, and polygonal shapes with well-demarcated cell borders. Individual cells may have either abundant eosinophilic, slightly granular cytoplasm or, alternatively, clear cytoplasm (Figure 8.1.5). The latter type of cell often shows a central nucleus with thin eosinophilic attachments (of cytoplasm) to the periphery of the cell. These are often called spider cells and are a feature more commonly associated with noncardiac forms of rhabdomyoma (Figure 8.1.6). On high-power magnification, intracellular crystalline material in a short rod-shaped configuration can sometimes be noted. True cross striations are often present as well. All subtypes of rhabdomyoma stain with markers of muscle differentiation including desmin, actin, and myogenin. Occasional cases of rhabdomyoma may express S100 protein antigen, possibly causing diagnostic confusion with granular cell tumor (GCT). The cytogenetic features of adult rhabdomyoma are not yet well characterized. Fetal rhabdomyoma is more uncommon than the adult form. Although any age may be affected, there appears to be a clustering of cases in the pediatric population. Fetal rhabdomyoma also tends to occur in the head and neck region. The posterior auricular region is one of the most common sites. Proptosis or airway obstruction are common presenting symptoms. Fetal rhabdomyoma is a completely benign lesion that is cured with surgical excision. This tumor has been molecularly characterized by a loss-of-function mutation in the tumor suppressor gene PTCH1. Histologically, the fetal form of rhabdomyoma is composed of primitive myotubule-like rhabdomyoblasts. The background is often edematous, and cross striations are usually identifiable. Mitoses may be frequent, but importantly, rhabdomyoma lacks necrosis, nuclear atypia, and pleomorphism. Another important feature is the lack of a “cambium layer” in the benign rhabdomyoma. This is a benign neoplasm arising in the male or female genital tract. In women, the tumor arises in the vulva and cervix. In men, it occurs in the spermatic cord, tunica, or paratesticular soft tissues. They present as lobulated, subepithelial or sumucosal soft tissue masses. Histologically, they are characterized by edematous stroma and scattered elongated or round rhabdomyoblasts. The rhabdomyoblasts of this subtype of rhabdomyoma usually have numerous cross striations. FIGURE 8.1.1 A cardiac rhabdomyoma from an infant with tuberous sclerosis complex. FIGURE 8.1.2 A rhabdomyoma arising near the base of the tongue in the oral cavity. FIGURE 8.1.3 Rhabdomyoma arising in the paranasal sinus region (arrow). FIGURE 8.1.4 On low power, rhabdomyoma consists of numerous enlarged cells with either clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm. FIGURE 8.1.5 The cells of rhabdomyoma are large and epithelioid in shape. FIGURE 8.1.6 A “spider” cell of rhabdomyoma. Granular cell tumors are lesions of schwannian origin that occur most commonly in the superficial soft tissues (Figure 8.2.1). In addition, GCTs are often identified in the breast, tongue, oral cavity, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. They tend to occur in middle-aged individuals, and up to 10% of affected patients have multiple GCTs. The vast majority of GCTs are benign, and surgical excision is curative. In a small subset, estimated at about 2% of cases, GCT behaves in a malignant fashion. Malignant GCTs are characterized by high rates of local recurrence and metastases to lung, lymph nodes, and bone. Histologic features associated with malignancy are discussed in the Histopathology section. In addition to histologic features of malignancy, size greater than 5 cm and older patient age are associated with a worse outcome. Interestingly, individuals with multiple GCTs tend to have either all superficial lesions or all visceral lesions. Multifocality does not seem to incur an increased risk of malignant behavior. In fact, malignant GCTs appear to develop de novo, not in association with a preexisting benign tumor. GCTs are usually very infiltrative. Tumors cells are often present as thin cords, strands, or even individual cells, which extend into neighboring muscle and soft tissues (Figure 8.2.2). Older lesions may be accompanied by a dense desmoplastic type of fibrous tissue (Figure 8.2.3). Individual cells have abundant pale, slightly granular cytoplasm, often with indistinct cell boundaries. The granules of GCT are numerous phagolysosomes. These often accumulate within the cell cytoplasm and form small aggregates of coarse debris surrounded by a halo of clear space. Nuclei tend to be small and regular, with a notable exception being the “atypical” or frankly malignant GCTs. Likewise, mitoses are infrequent in the benign form of GCT. Granular cells are often seen in association with nerves, similar to the perineural type of spread associated with some malignancies (Figure 8.2.4). In GCT, the presence of perineural spread does not correlate with unfavorable prognosis. Ancillary studies have relatively little value in the diagnosis of GCT because it tends to be very straightforward on routine hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) sections. In more difficult cases, immunohistochemical staining for S100 protein can be performed. GCTs stain strongly and diffusely positive for S100 protein. This feature can also be used to delineate the extent of tumor spread for the evaluation of surgical margins. Of note, GCTs are negative for HMB-45 and Melan A, useful negative markers to help exclude a melanoma. As mentioned previously, a small subset of GCTs behave in an aggressive fashion. Features that correlate with an increased likelihood of malignant behavior include the following: marked nuclear atypia, increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli, cell “sarcomatoid” spindling, necrosis, mitotic rate greater than 2 mitoses per 10 high-power fields (hpf) and diffuse pleomorphism. The presence of one or two of these features is enough to warrant a diagnosis of “atypical granular cell” tumor, whereas the presence of three or more of these criteria should raise the possibility of a true malignant GCT (Figure 8.2.5). An additional feature associated with potentially aggressive behavior includes Ki-67 index greater than 10%. Despite the careful application of these diagnostic criteria, some seemingly benign tumors on histology will ultimately display malignant behavior despite their innocuous appearance. As such, estimation of a GCT’s malignant potential by histology is still a very imperfect strategy. Aspirates of GCT are typically moderately cellular. The background often has abundant debris giving the specimen an overall “dirty” appearance. This debris is often accompanied by stripped GCT nuclei, reflecting the fragile nature of the granular cells. Intact cells have a polygonal shape and abundant coarsely granular cytoplasm (Figure 8.2.6). They are often present singly or in small syncytial aggregates. Nuclei are usually small and round with a prominent small nucleolus. FIGURE 8.2.1 A typical location for granular cell tumor (GCT) beneath the skin. Note that the lesion is poorly delineated and extends into the adjacent soft tissues. FIGURE 8.2.2 GCTs tend to be very infiltrative and extend into fat and skeletal muscle. FIGURE 8.2.3 Some GCTs elicit a marked desmoplastic response in the corresponding host tissues. FIGURE 8.2.4 GCTs tend to display perineural invasion. This histologic feature is not necessarily associated with aggressive behavior. FIGURE 8.2.5 Histologic features that are associated with potential aggressive behavior include spindling of tumor cells, necrosis, prominent nucleoli, increased mitotic activity, and nuclear pleomorphism. The presence of one or more of these features should raise the possibility of potential malignant behavior. FIGURE 8.2.6 Aspirates of GCT tend to have a “grungy” appearance due to the disruption of cytoplasmic contents. Intact cells are often large and polyhedral with coarsely granular cytoplasm. Glomus tumors are fairly uncommon neoplasms of a specialized form of smooth muscle, normally associated with the glomus body or glomus apparatus of the skin. Glomus tumors comprise an estimated 1% to 2% of all soft tissue tumors with a peak incidence in young adults. The vast majority of glomus tumors are small (<1 cm) and located in the superficial soft tissues of the distal extremities. The subungual region of the finger is a particularly common site. Glomus tumors tend to be very painful, particularly when exposed to extremes in temperature. Rare cases of glomus tumor are sited in the deep soft tissues or viscera. Glomus tumors are solitary, but there is a familial form of the tumor where lesions tend to be multifocal. The vast majority of lesions are sporadic; the multifocal form of disease probably accounts for less than 10% of all tumors. The familial form of glomus tumor is associated with defects in the GLMN (glomulin) gene. The syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, and the tumors often present in early childhood. In addition to multifocality, the familial form of the disease is often associated with a more infiltrative form of the tumor (glomangiomatosis). The vast majority of glomus tumors are benign and are cured by local excision. Rare glomus tumors recur after excision. These are usually of the “infiltrative” type seen in the hereditary or familial form of disease. There are very rare cases of malignant glomus tumor. There is considerable variation in the histologic appearance of glomus tumors. “Typical” glomus tumors are also sometimes referred to as solid glomus tumors and represent the most common phenotypic variant. Individual cells are arranged in a solid sheet or nesting pattern around small vessels (Figure 8.3.1). There is often focal hyalinization of small vessel walls, giving the vasculature a prominent appearance (Figure 8.3.2). The glomus cells tend to be very round and uniform in size and shape. The individual glomus cells tend to have very sharply defined cytoplasmic borders and round, regular nuclei (Figure 8.3.3). Mitotic activity should be minimal. The vasculature of glomus tumors often becomes more dilated and prominent in the “glomangioma” variant of glomus tumor (Figure 8.3.4). This variant often shows a histologic resemblance to benign vascular tumors, particularly the cavernous form of hemangioma. Glomangiomas tend to be more prevalent in the familial form of glomus tumor. Rare glomus tumors display a stag horn-like vascular pattern. These have been referred to in the past as “glomangiopericytoma” (also called myopericytoma or perivascular myoma). Glomus tumors with a well-developed smooth muscle component are termed glomangiomyomas. Additional variations in glomus tumor histology include the presence of an epithelioid or oncocytic subtype and occasional “symplastic” features. Although extremely rare, malignant glomus tumors occasionally occur. Malignant or aggressive behavior is correlated with the following: deep-seated location, size greater than 2 cm, marked nuclear atypia, and elevated mitotic rate (more than 5 mitoses per 50 microscopic high power fields), and atypical mitotic figures. Metastases have been documented with the malignant form of glomus tumor. Ancillary studies can be helpful for the confirmation of a glomus tumor. By immunohistochemistry, glomus tumors typically stain strongly and diffusely positive for smooth muscle actin (Figure 8.3.5). They also stain for muscle-specific actin, but tend to be negative for desmin. Glomus cells can be focally positive for CD34 antigen, usually when they are in continuity with a large vascular structure. Negative staining for S100 protein may be helpful in eliminating melanocytic nevus, which resembles glomus tumor histologically. Due to their painful nature, glomus tumors do not make good targets for aspiration biopsy diagnosis. There are rare descriptions of successful aspirations of glomus tumor. The cytologic features documented to date include a uniform round cell population with smooth nuclear membranes and uniform chromatin (Figure 8.3.6). FIGURE 8.3.1 A glomus tumor sited directly beneath the epithelium. FIGURE 8.3.2 Glomus tumors frequently show mild perivascular hyalinization. FIGURE 8.3.3 Individual glomus cells are round and regular with distinct cytoplasmic boundaries. FIGURE 8.3.4 Glomangiomas have ectatic vessels lined by one or two layers of glomus cells. FIGURE 8.3.5 A glomus tumor demonstrating diffuse and strong immunohistochemical staining for smooth muscle actin. FIGURE 8.3.6 Aspirates of glomus tumor show small regular cells with uniform nuclei. 8.4 Neoplasms With Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Differentiation (PEComa) PEComas are tumors arising from perivascular epithelioid cells (PECs). These cells were thought to originate from blood vessel walls and show evidence of both smooth muscle and melanocytic differentiation. Currently, the category PEComa is an umbrella term, which encompasses a wide variety of neoplasms that were previously considered separate entities. These include the renal and extrarenal angiomyolipoma (AMLs) (Figure 8.4.1), clear cell (sugar) tumor of the lungs, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, clear cell myomelanocytic tumor of the falciform ligament, and abdominopelvic sarcoma of PECs (Figure 8.4.2). Of all these entities, AML appears to be the most common. PEComas of various sites, but particularly AML and lymphangioleiomyomatosis, are associated with tuberous sclerosis complex. PEComas are increasingly recognized in a variety of sites, both visceral and in bone and soft tissue. Prognosis of any given tumor is associated with tumor site. In addition, there are some histologic features that can be used to assess for potentially aggressive behavior. The latter are summarized in Table 8.4.1. AML is by far the most common of the PEComas. As previously mentioned, AML is associated with the tuberous sclerosis complex and is linked to mutations of the associated genes TSC1 (9q34) and TSC2 (16p13.3). Nevertheless, 50% or more of AMLs are sporadic and occur outside of tuberous sclerosis. Both sporadic and syndromic AMLs contain mutations in the TSC genes.

ADULT RHABDOMYOMA

FETAL RHABDOMYOMA

GENITAL RHABDOMYOMA

HISTOPATHOLOGY

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

HISTOPATHOLOGY

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FINDINGS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree