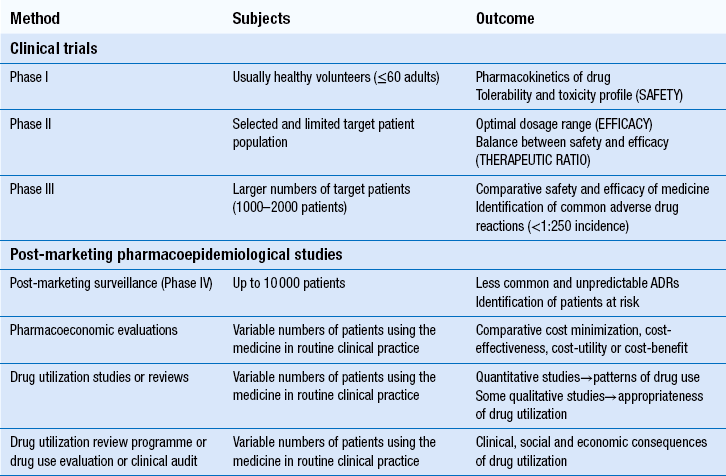

22 The volume, complexity and costs of modern medicines are increasing. The need to compare the therapeutic efficacy (i.e. benefits) of medicines with their potential to cause harm (i.e. risks) and the economic implications of these is of paramount importance to the pharmaceutical industry, to healthcare providers and to society. Pharmacists play a major role in evaluating the safety, efficacy and economics of medicines use. At a macro-level, the pharmaceutical industry decides which line of drug development would best serve its shareholders’ interests. New chemical entities which show promise must be studied in clinical trials before they can be marketed as medicines (see Ch. 4). After products are licensed and marketed, society and its healthcare systems are then faced with difficult decisions about which specific patient populations to treat, or which new medicines to approve for use. Increasingly, decisions are based on economic evaluations, which attempt to calculate cost:benefit ratios for medicines in potential patient populations. In some countries, only medicines which have a clear cost-effective advantage over existing treatment are funded by government. In the UK, various organizations work in differing ways to examine this aspect of medicine evaluation. At a micro-level, clinicians (doctors, pharmacists or nurses) must then assess the relative harms and benefits of each medicine for individual patients. This involves consideration of factors which can affect drug disposition, efficacy and safety, such as concurrent disease states or other medicines, while also weighing up the risk of untreated disease and potential affordability. As pharmacists become more involved in selecting treatments, the importance of skills in evaluating all these factors to make individual clinical decisions increases. Furthermore, pharmacists are frequently required to evaluate the use of medicines in individual patients prescribed by others. This involves the further skills of drug use review and evaluation. The techniques used in the evaluation of medicines for safety, efficacy and efficiency at pre- and post-marketing stages are summarized in Table 22.1. In most countries, evidence of safety, efficacy and quality must be presented to government-appointed regulatory authorities before a new product can be marketed. Manufacturers wishing to market a product in the UK, can apply to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), or to the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Either body must be satisfied with the evidence provided before a marketing authorization (formerly called a product licence) can be granted. The MHRA and EMA have responsibility for assuring the public that all medicines which reach the UK or European markets have been assessed for safety, efficacy and quality. Cost issues are not taken into consideration. Efficacy has to be balanced against toxicity for each product and, while the MHRA’s evaluation includes the active ingredients of a product and its formulation, final decisions must also take into account the nature of the disease to be treated and the duration of the treatment. What is an acceptable benefit to risk ratio may differ for a medicine used to prolong survival in terminal conditions compared to a treatment for symptomatic relief of short-term symptoms. These trials provide only limited safety data, because the subjects are healthy adults and unlikely to have any compromised drug handling ability. Thus, the potential risks of using the drug in patients at extremes of age, or in those with poor hepatic or renal function, are not known. There are also few subjects (e.g. 50–60), so only very common ADRs are detected. These trials examine safety and efficacy. They are generally large-scale studies comparing a new medicine with other treatments or placebo. Where possible, they should have a randomized controlled design, which is generally accepted as the least biased method of conducting clinical research. Assigning each patient randomly to either the new treatment or control helps to prevent bias (see Ch. 20). Once the licensing authority is satisfied that a product is safe, efficacious and of suitable quality, it grants a marketing authorization, which means that the product can then be promoted to prescribers. This usually results in a large increase in the numbers of patients using the product and it is important that its safety is continuously monitored. The MHRA operates a system of post-marketing surveillance which involves spontaneous reporting of suspected ADRs, similar to that in many other countries. It is known as the Yellow Card scheme (see Ch. 51) and anyone can report suspected ADRs to the MHRA. Such schemes provide early warning signals of potential problems and can lead to hypotheses about associations between a medicine and an effect. These can then be tested using retrospective (e.g. case–control studies) or prospective studies (e.g. cohort studies). The main problems with spontaneous reporting schemes are under-reporting, difficulty in identifying new ADRs and the fact that incidence cannot be calculated, since there is no information on the number of patients exposed to the medicine. The benefits of patients reporting their ADRs to the MHRA have been formally evaluated and it has been shown that patient reports add to the usefulness of data obtained through reports submitted by healthcare professionals. European legislation now requires all member states to develop systems enabling patients to report ADRs to the national medicines regulator. Case–control studies retrospectively identify patients who have developed a particular ADR and determine their level of exposure to the suspected medicine. This is then compared to a control group of patients without the ADR of interest. Case–control studies are smaller, much less expensive and generate results more quickly than cohort studies. They are used to investigate suspected ADRs identified by other means, e.g. cohort studies or spontaneous reporting and are particularly useful for confirming type B ADRs. They are capable of establishing whether an ADR is caused by a medicine, but cannot measure the incidence of ADRs. Most herbal remedies are not licensed medicinal products and therefore no evaluation is required before they are marketed, but manufacturers can apply to the MHRA for a marketing authorization. Currently around 500 herbal products hold a marketing authorization and so must have fulfilled the same criteria of safety, quality and efficacy (or effectiveness) as any other medicine and be accompanied by a patient information leaflet. Efficacy has not been demonstrated for most herbal medicinal products, therefore manufacturers can instead have the safety and quality formally assessed and recognized through the traditional herbal medicines registration scheme (see Ch. 24). Once a product is licensed, decisions must be made about whether it should be used. Local decisions may be made by drug and therapeutics committees (see Ch. 23). On a larger scale, decisions on whether new treatments should be available on the NHS in the UK are made by NICE, the Scottish Medicines Consortium and the All Wales Medicines Strategy Group. Pharmacoeconomic evaluations play a central role in informing NICE’s decisions, so pharmacists may conduct economic evaluations and certainly need to understand them. It is important to appreciate how NICE’s work differs from that of the MHRA, who decide whether products can be sold in the UK, by comparing benefits to risks. NICE considers whether medicines should be bought by the NHS, by comparing benefits to costs, i.e. whether they are cost-effective. Few diseases are left completely untreated (because it would not be fair or equitable) but normally, efficiency demands that most of our scarce resources are used to maximize health gains for the greatest number of people. This philosophy is called utilitarianism. If people whose health status cannot be improved by health care are treated, there are fewer resources to help those who can benefit.

Drug evaluation and pharmacoeconomics

Safety, efficacy and economy

Pre-marketing studies

Phase I trials

Phase III trials

Post-marketing studies

Herbal and homoeopathic medicines

Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of medicines

Basic economic principles

Opportunity cost

Technical efficiency is about achieving particular goals on a fixed scale in the most appropriate way (e.g. comparing a range of interventions, including medicines and lifestyle changes, within a programme to reduce blood pressure)

Technical efficiency is about achieving particular goals on a fixed scale in the most appropriate way (e.g. comparing a range of interventions, including medicines and lifestyle changes, within a programme to reduce blood pressure)

Allocative efficiency is concerned with choosing the right goals in the first place (e.g. coronary heart disease prevention or treating lung cancer) and the most appropriate scale for a healthcare programme.

Allocative efficiency is concerned with choosing the right goals in the first place (e.g. coronary heart disease prevention or treating lung cancer) and the most appropriate scale for a healthcare programme.

Supply and demand

Health is demanded but cannot be directly provided

Health is demanded but cannot be directly provided

The link between health care and improvements in health is uncertain

The link between health care and improvements in health is uncertain

We do not know when we will be ill

We do not know when we will be ill

Providers of health care have more information than consumers

Providers of health care have more information than consumers

Insurance companies or governments usually pay for health care – not consumers.

Insurance companies or governments usually pay for health care – not consumers.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Drug evaluation and pharmacoeconomics

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue