(1)

Department of Pathology, Rutgers-New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ, USA

Keywords

Congenital anomaliesAmbiguous genitaliaImperforate hymenInfantile perianal pyramidal protrusionVulvar ulcersVestibular adenosisLichen sclerosusCysts of the vulvaEpidermal inclusion cystEndometriosis/endometriomaMucinous cyst/ciliated cyst of vestibuleBartholin’s duct cystCyst of canal of nuckSkene’s duct cystLymphangioma circumscriptumCondyloma accuminatumMicropapillomatosis labialisMolluscum contagiosumHidradenitis suppurativaNoninfectious inflammatory diseases of the vulvaLichen planusSquamous cell hyperplasiaLentigoNevusSeborrheic keratosisAngiokeratomaAcanthosis nigricansPost-inflammatory hyperpigmentationSkin tagSyringomaGranular cell tumorFibromaLeiomyomaHemangiomaHidradenoma papilliferumAggressive angiomyomaVulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)Differentiated VINPaget’s diseaseSquamous cell carcinomaSuperficially invasive squamous cell carcinomaMelanomaLeiomyosarcomaBasal cell carcinomaVerrucous carcinomaAnal intraepithelial neoplasiaAnal carcinoma3.1 Diseases of the Vulva

The vulva is both a dermatologic and gynecologic organ, and thus prone to conditions affecting both. Clinical history is important, and orientation of excisions is critical if marginal assessment is required (Tables 3.1 and 3.2). There are limitations specific to the interpretation of vulvar biopsies (Table 3.3). Some conditions do not have a specific diagnosis, and a descriptive diagnosis may be received. Common dermatologic terms used in the vulva are listed in Table 3.4.

Table 3.1

What to tell the pathologist about a vulvar lesion

Clinical history |

Exact location of lesion |

Orientation of specimen, particularly if marginal evaluation is needed |

Table 3.2

History provided affects the diagnosis

Case 1 |

Clinical history A provided: vulvar cyst |

Pathology report: benign mucinous cyst |

Clinical history B provided: vulvar cyst, clinically Bartholin’s cyst |

Pathology report: benign mucinous cyst consistent with Bartholin’s duct cyst |

Case 2 |

Clinical history A provided: vulvar cyst |

Pathology report: squamous mucosa containing a thin-walled squamous epithelial-lined cyst |

Clinical history B provided: cystic mass at lateral introitus |

Pathology report: squamous epithelial-lined cyst consistent with Bartholin’s duct cyst |

Table 3.3

Limitations of vulvar biopsy

May not be able to provide location of positive margin without prior orientation |

Superficial biopsy may be nondiagnostic in thick lesions such as verrucous carcinoma |

Lack of provided location may decrease accuracy of diagnosis of type of cyst |

Table 3.4

Glossary of vulvar dermatology terms

Hyperkeratosis—increased thickness of the keratin layer without nuclei |

Parakeratosis—increased thickness of the keratin layer. Nuclei are present |

Acanthosis—thickening and fusing of the rete pegs |

Rete peg—epithelial extension into dermis |

Dermal papillae—dermal projections up into epidermis |

Granular cell layer—the layer just below the keratin, containing keratohyaline granules |

Koilocytosis—cells containing atypical nuclei with a perinuclear halo. Cytopathic effect of HPV |

Papillomatosis—skin surface elevations |

Metaplasia—change from one benign tissue type to another |

Desmoplasia—fibrosis |

3.2 Congenital Anomalies of the Vulva

3.2.1 Ambiguous Genitalia

A discussion of the complex subject of intersex disorders is beyond the scope of this text. In an XX individual, the most common cause of newborn ambiguous genitalia is in utero exposure to androgens, either due to congenital adrenal hyperplasia, or maternal endogenous or exogenous androgens, resulting in female pseudohermaphroditism. Here the term “female” corresponds to the presence of an ovary. Clitoromegaly and labial fusion of various degrees may be seen in such cases.

3.2.2 Imperforate Hymen

Imperforate hymen, due to persistence of the urogenital membrane, may not present until after puberty, with hematocolpos, or difficulty with first intercourse. Rarely, accumulation of secretions may make this condition present as a congenital or newborn condition, presenting as an abdominal cyst [1].

3.3 Pediatric and Adolescent Lesions of the Vulva

3.3.1 Infantile Perianal Pyramidal Protrusion

This lesion of unknown etiology is characterized by a small fleshy protuberance anterior to the anus (Fig. 3.1). Reported cases have been almost entirely in females [2]. The lesion may be constitutional, acquired, most often in association with constipation, or associated with lichen sclerosus [2]. It may regress spontaneously. Associated conditions should be treated appropriately.

Fig. 3.1

Infantile perianal pyramidal protrusion*. A small fleshy protuberance is seen anterior to the anus. *Copyright Libby Edwards, MD. Used with permission. All permission requests for this image should be made to the copyright holder

3.3.2 Vulvar Ulcers in Adolescents

Vulvar ulcers in young girls may represent apthae, or Epstein–Barr virus infection, in addition to possible sexually transmitted diseases. Apthae are painful ulcers of unknown etiology associated with systemic symptoms [3]. They may be associated with oral apthae (canker sores), and if associated with systemic symptoms, particularly uveitis, this constitutes Behçet’s disease [4]. Epstein–Barr vulvar ulcers are also painful and present with flu-like symptoms [5]. A systematic history and workup is helpful, as the differential diagnosis of vulvar ulcers is broad, with the most common etiology in North America being Herpes Simplex [6]

3.3.3 Vestibular Adenosis

Adenosis is the persistence of glands in areas where there is usually only squamous epithelium, such as the vestibule or vagina. Adenosis is thought to be due to a disturbance in embryogenesis during the urogenital sinus meeting up with the fused Müllerian ducts. The most common location is upper vagina, but adenosis can rarely occur on the vulva or vestibule. In those locations, some have occurred secondary to prior Stevens–Johnson syndrome or CO2 laser therapy [7]. While there has historically been an association of adenosis with in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES), the condition can arise spontaneously. In the vestibule, the lesion may present as red friable tissue that resembles granulation tissue and is tender. Histologically, glands of endocervical, endometrial, or tubal type epithelium are seen under the surface squamous epithelium, often repairing by squamous metaplasia (Fig. 3.2).

Fig. 3.2

Adenosis-subepithelial glands are seen repairing by squamous metaplasia

3.3.4 Lichen Sclerosus

There are two age peaks to vulvar lichen sclerosus, childhood and in postmenopausal women. Children who have lichen sclerosus may appear to have significant improvement or even regression in adolescence, but must be followed indefinitely, to evaluate for architectural disturbances, and due to the increased risk of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma [8]. The pathologic features of lichen sclerosus are discussed with the noninfectious dermatoses.

3.4 Cysts of the Vulva

A variety of benign cysts may occur on the vulva or in the vagina. Attention to the location may provide the origin of the cyst; however, even with that information, it may not be possible to determine the exact origin of some of these cysts. Clinicians should provide the pathologist with the location of the cyst, as this will lead to more precision in the pathology report (see Table 3.2).

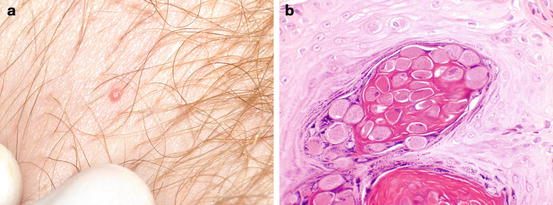

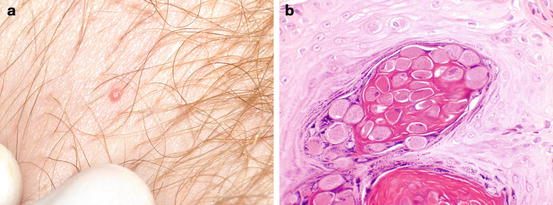

3.4.1 Epidermal Inclusion Cyst

Epidermal inclusion cysts of the vulva are very common. They may be due to prior surgical intervention such as episiotomy, but can arise de novo. Clitoral epidermal inclusion cysts can arise in association with female genital cutting/circumcision [9]. Epidermal inclusion cysts may also arise on hair-bearing portions of the vulva. The keratinaceous debris produces the contents of the cyst, which grossly appear cheesy (Fig. 3.3a). Histologically, these cysts are lined by keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium (Fig. 3.3b).

Fig. 3.3

Epidermal inclusion cyst. Grossly, the contents contain yellow cheesy material (a*). Histologically, the cyst is lined by keratinizing squamous epithelium, with cyst contents comprised of keratinaceous debris (b). *Copyright Libby Edwards, MD. Used with permission. All permission requests for this image should be made to the copyright holder

3.4.2 Endometriosis/Endometrioma

Endometriosis may present as a cystic or nodular mass on the vulva, most often in a prior episiotomy site, supporting implantation as the origin [10]. It may cycle with the menstrual cycle, swelling and bleeding and causing pain. Grossly, it may appear blue tinged. Histologically, as in endometriosis elsewhere, endometrial glandular epithelium and stroma, not just old hemorrhage, must be present to confirm the diagnosis histopathologically (Fig. 3.4).

Fig. 3.4

Endometriosis. The lesion is composed of endometrial glands and stroma

3.4.3 Mucinous Cyst/Ciliated Cyst of Vestibule

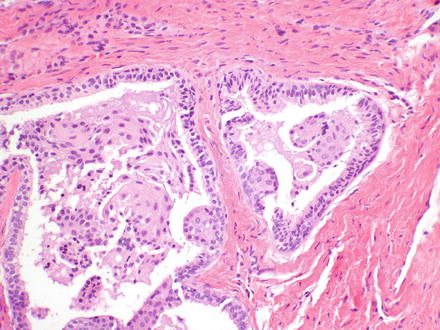

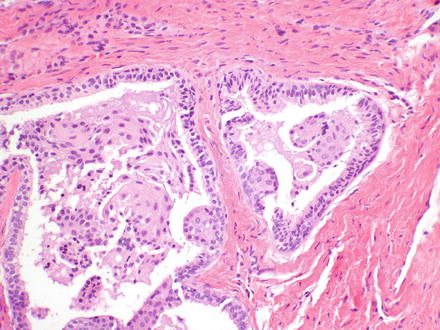

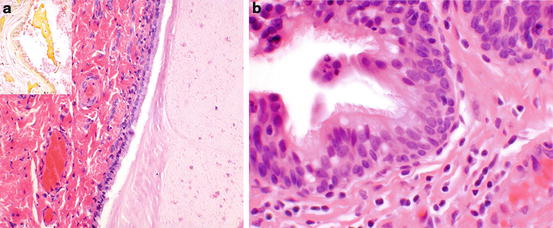

Cysts lined by mucinous or ciliated epithelium (Fig. 3.5a, b) may arise in the vestibule. The origin of these cysts is controversial. They may arise from Müllerian remnants, particularly in the vagina; however, in the vestibule may arise from minor vestibular glands. Another possible origin is arising in adenosis.

Fig. 3.5

Mucinous/ciliated cysts of the vulva. Mucinous cyst (a) is lined by mucinous columnar epithelium. Mucicarmine staining (inset) highlights the mucin (fuchsia staining material). Ciliated cyst (b) showing ciliated lining

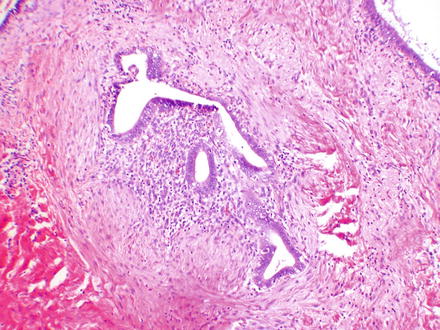

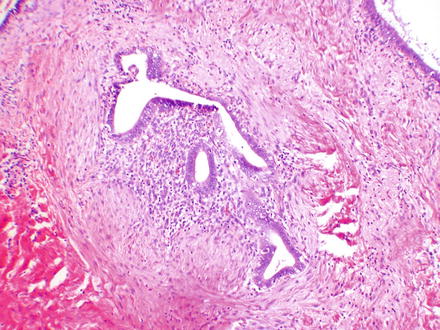

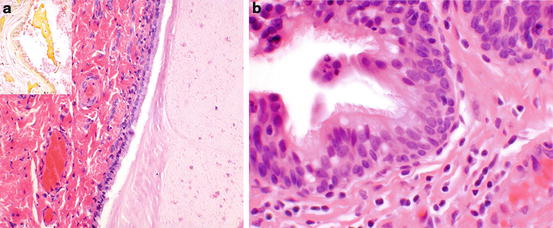

3.4.4 Bartholin’s Duct Cyst

Bartholin’s duct cysts are often marsupialized, but a surgical excision may be performed for recurrence, or in a woman over 40 to rule out a carcinoma. The cysts may be lined by any of the epithelial types encountered in the gland or duct, or a mixture of glandular, transitional, and squamous epithelium (Fig. 3.6a, b).

Fig. 3.6

Bartholin’s duct cyst at its characteristic location (a*). This cyst is lined by a mix of transitional and mucinous epithelium consistent with Bartholin’s duct (b). *Copyright Libby Edwards, MD. Used with permission. All permission requests for this image should be made to the copyright holder

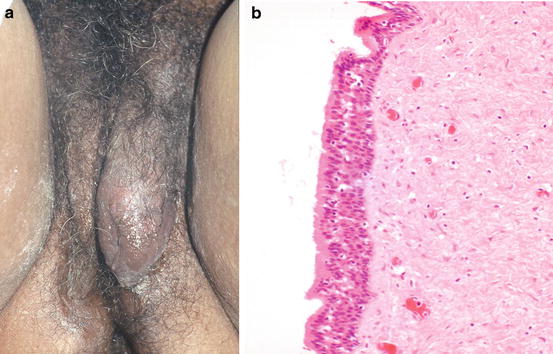

3.4.5 Cyst of Canal of Nuck

The Canal of Nuck is the parietal peritoneum that accompanies the round ligament through the inguinal canal. If it fails to obliterate, a cyst can develop, equivalent to a male hydrocele, and may mimic an inguinal hernia. It is lined by a flattened mesothelium consistent with peritoneum (Fig. 3.7a, b).

Fig. 3.7

Cyst of the canal of nuck. Clinically, a cyst of the canal of nuck may mimic an inguinal hernia (a*). It is lined by mesothelium (b). *Copyright Libby Edwards, MD. Used with permission. All permission requests for this image should be made to the copyright holder

3.4.6 Skene’s Duct Cyst

Skene’s duct cysts are uncommon. They are best suspected by the paraurethral location. It is important to consider other masses that may arise on the anterior vaginal wall, such as ectopic ureterocele, and additional imaging studies may be indicated prior to surgery. Skene’s duct cysts may be seen in newborns as well as adults and may resolve spontaneously. Histologically, they may be lined by transitional, ciliated columnar, or squamous epithelium [10].

3.4.7 Lymphangioma Circumscriptum

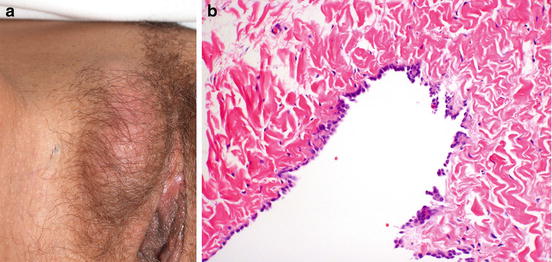

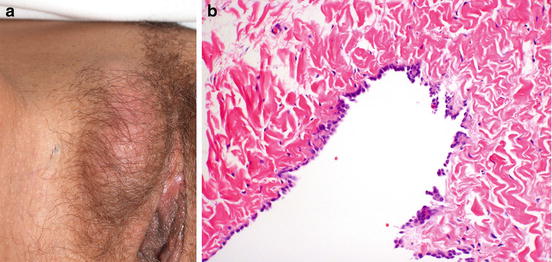

This lesion may be congenital or acquired. Secondary causes include prior surgery, radiation, or infection [11]. Clinically the lesion is said to resemble frog spawn, but it may be interpreted clinically as condylomata acuminata. It is difficult to treat and is comprised of multiple oozing dilated lymphatic channels that cluster as vesicles (Fig. 3.8a, b). Recurrence can occur after excision, and laser therapy has also been utilized [11].

Fig. 3.8

Lymphangioma circumscriptum. Vesicles seen in a patient with hidradenitis suppurativa (a*). The vesicles are dilated lymphatics (b) containing numerous lymphocytes (inset). *Copyright Libby Edwards, MD. Used with permission. All permission requests for this image should be made to the copyright holder

3.5 Infections and Inflammations of the Vulva

3.5.1 Ulcers

The differential diagnosis for ulcers of the vulva is large, and so a systematic approach is needed. Vulvar specialists have divided vulvar ulcers into infection, dermatoses, tumors, trauma, and miscellaneous [12]. Infection may be sexually transmitted. Clinical history and investigation of possible infectious agents are good first steps. Biopsy may be part of the workup; however, some of the conditions that cause vulvar ulceration do not have pathognomonic findings on histopathology. Syphilis may show increased plasma cells and vasculitis, raising suspicion, but biopsy does not necessarily confirm the diagnosis unless organisms can be identified on special stains. Lymphogranuloma venereum, chancroid, and granuloma inguinale do not have specific histologic findings. Herpes simplex virus can sometimes be confirmed by the presence of the characteristic intranuclear inclusions (Fig. 3.9a, b). Crohn’s disease, which presents with characteristic knife-cut ulcerations, or fistulas, may show granulomatous inflammation, with multinucleated giant cells, but clinical confirmation is necessary (Fig. 3.10).

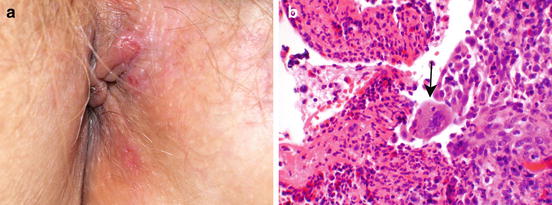

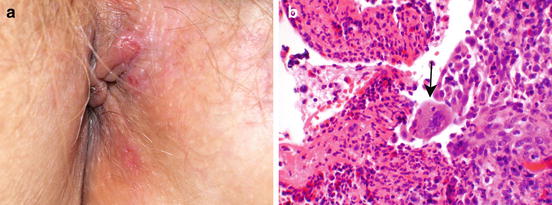

Fig. 3.9

Herpes. Characteristic erosion seen after rupture of the vesicles (a*). Histologically, herpes (b, arrow) is characterized by multinucleation with ground glass nuclei. Sometimes Cowdry A intranuclear inclusions may be seen (not shown). *Copyright Libby Edwards, MD. Used with permission. All permission requests for this image should be made to the copyright holder

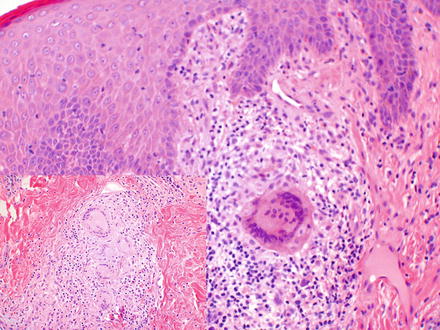

Fig. 3.10

Crohn’s disease. Granulomatous vulvitis in a patient with a history of gastrointestinal Crohn’s disease. Note well-formed granuloma (inset) with multinucleated giant cells

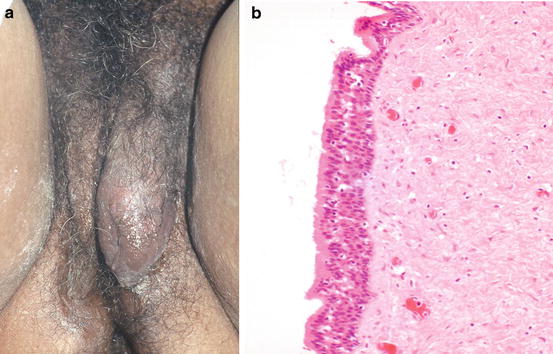

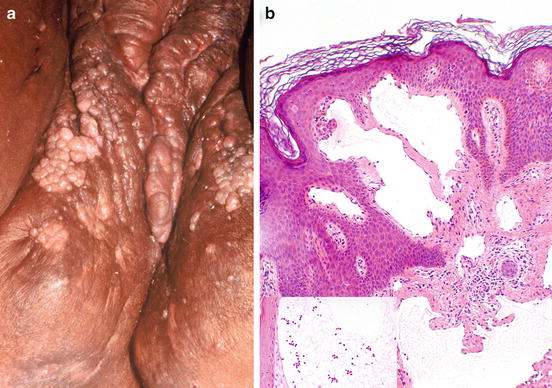

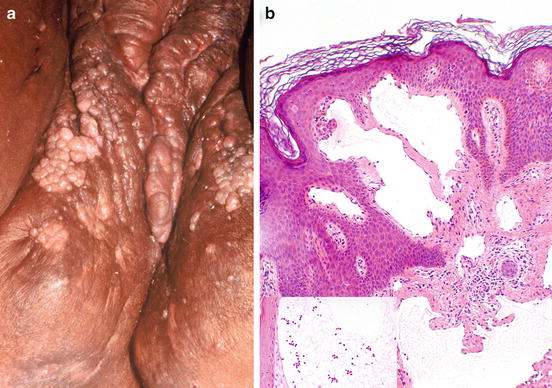

3.5.2 Condyloma Acuminatum

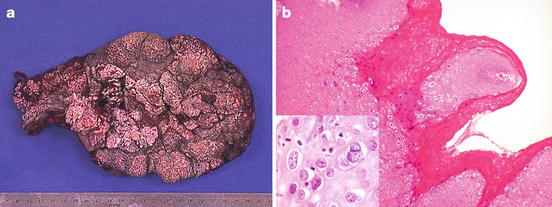

Most vulvar condylomas are caused by low-risk HPV types 6 or 11 and are sexually transmittable. The histology corresponds to the gross appearance, and there is hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and koilocytosis (Fig. 3.11a, b). Koilocytosis derives from the Greek word Koilos, which means empty. The koilocyte is a cell with an abnormally enlarged and irregular nucleus with a perinuclear halo. The koilocyte is the cytopathic manifestation of the human papillomavirus.

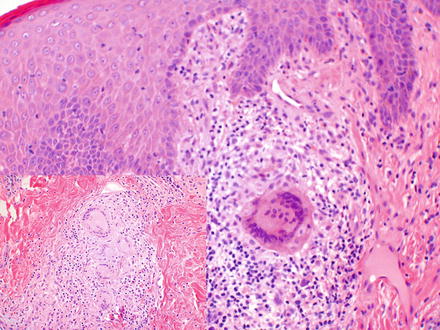

Fig. 3.11

Condyloma acuminatum. This excision (a) shows the features that correspond to the histologic finding of papillomatosis (b). Inset shows koilocytosis and multinucleation

Condylomas may be overdiagnosed both by clinicians and pathologists. Normal vulvar glycogenated epithelium is not koilocytosis, which requires the presence of nuclear atypia to make the diagnosis. A variety of papillary lesions may clinically be considered as condyloma. A very common one is micropapillomatosis labialis (Fig. 3.12). Uniform finger-like projections are seen in the vestibule. Histologically, they lack koilocytosis. Micropapillomatosis is considered a normal anatomic variant and is not caused by Human papillomavirus.

Fig. 3.12

*Micropapillomatosis labialis showing more uniform finger-like projections than is seen with condyloma acuminatum. Micropapillomatosis is a normal variant. *Copyright Libby Edwards, MD. Used with permission. All permission requests for this image should be made to the copyright holder

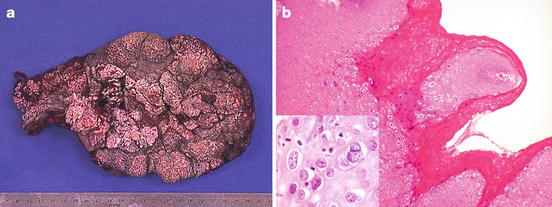

3.5.3 Molluscum Contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by a pox virus infection and most commonly seen in children, with characteristic pruritic umbilicated papules over the body (Fig. 3.13a). Occasionally they can occur on the vulva of adults, either singly or in groups. They will eventually regress, however may be excised when the diagnosis is unknown, or the lesions may be scraped as therapy. Histologically, the characteristic intracytoplasmic viral inclusions may be seen (Fig. 3.13b)

Fig. 3.13

Molluscum contagiosum. Typical umbilicated lesion (a*). Histology shows the characteristic intracytoplasmic eosinophilic viral inclusions (b). *Copyright Libby Edwards, MD. Used with permission. All permission requests for this image should be made to the copyright holder

3.5.4 Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Hidradenitis is a potentially debilitating condition that occurs in sites with abundant apocrine glands, including the groin and axilla. It is more common in women. The cause is unknown, but it is associated with obesity [13]. Clinically it presents as numerous draining boils and sinuses with scarring (Fig. 3.14). Although medical management may be attempted, severe cases may come to surgery. Histology is nonspecific, with severe inflammation, often near apocrine glands.