(1)

Department of Pathology, Rutgers-New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ, USA

Keywords

UterusEndometriumEndometritis, acuteEndometritis, chronicEndometrium, hormonal effectsEndometrial polypsDisordered proliferationSimple hyperplasiaComplex hyperplasiaAtypical hyperplasiaTreated endometrial hyperplasiaEndometrial adenocarcinomaUterine serous carcinomaClear cell adenocarcinoma of endometriumMalignant mixed mesodermal tumorAdenosarcoma6.1 Lesions of the Endometrium

Endometrial biopsies are among the more common gynecologic specimens received by a pathology laboratory. Most biopsies are performed for abnormal uterine bleeding. Abnormal uterine bleeding can be thought of in categories, including organic (structural abnormalities such as polyps or leiomyomas), dysfunctional (hormonal flux), hyperplastic, or neoplastic. The age and menstrual status of the patient make certain lesions more likely at different stages of life. For example, anovulation is an underlying etiology for abnormal bleeding at both ends of the reproductive spectrum.

Endometrial biopsies may provide abundant or scant tissue, based on the lesion, the age and hormonal status of the patient, and sometimes the skill of the operator. Clinicians should be aware that what appears as a great deal of tissue may be mostly blood clot. A clinical history is extremely helpful for the pathologist, as there are many processes that, while benign, do not match up with what is in histology books. Pertinent history includes age, last menstrual period, any recent pregnancy, any prior pertinent surgery such as curettage, myomectomy, or ablation, endometrial instrumentation or IUD use, and any hormonal therapy that may impact on the endometrium. In the absence of an appropriate history, for example of exogenous hormones, a longer and less clear report may result (see Tables 6.1 and 6.2).

Table 6.1

Importance of providing clinical history with an endometrial biopsy

Report 1 without history |

– Endometrium showing decidualized stroma and small inactive glands. This finding may represent exogenous progestin effect. Clinical correlation suggested |

Report 1 with history |

– Benign endometrium with features consistent with progestin effect |

Report 2 without history |

– Irregularly developed endometrium with proliferative areas and secretory areas. There is focal glandular crowding |

Report 2 with history |

– Irregularly developed benign endometrium consistent with history of hormone replacement therapy |

Table 6.2

Key points about endometrial pathology

– An abundant biopsy may represent estrogen effect, hyperplasia, neoplasia, or benign endometrium stimulated by hormones (late proliferative, secretory) |

– A scant biopsy may represent atrophy, prolonged bleeding, Asherman’s syndrome, drug effect (i.e., GnRH agonists, progestins), cervical stenosis, or operator inexperience |

– Partially treated (by progestins) atypical endometrial hyperplasia may show glandular crowding but atypia can no longer be assessed |

6.2 Infections and Inflammations of the Endometrium

6.2.1 Acute Endometritis

Acute endometritis is not a common finding. It was more commonly seen in the era of illegal septic abortions. Histologically, a neutrophilic infiltrate is seen within glands, forming microabscesses and involving and “chewing on” the glandular epithelium (Fig. 6.1). This needs to be distinguished from the normal physiologic neutrophils associated with breakdown of endometrium with menses, or decidua after a gestation, where inflammation does not signify infection. In menstrual breakdown, there is not the formation of microabscesses, and the neutrophils are not specifically involving glandular epithelium.

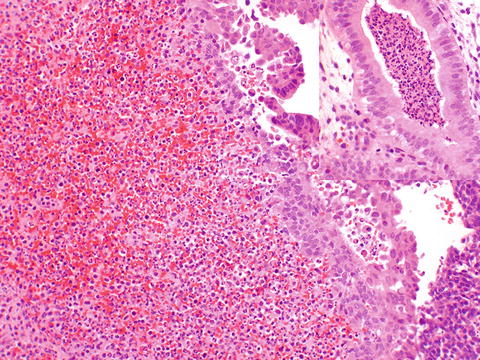

Fig. 6.1

Acute endometritis, with a neutrophilic infiltrate replacing stroma. This purulent exudate can also be seen involving glands (inset)

6.2.2 Chronic Endometritis

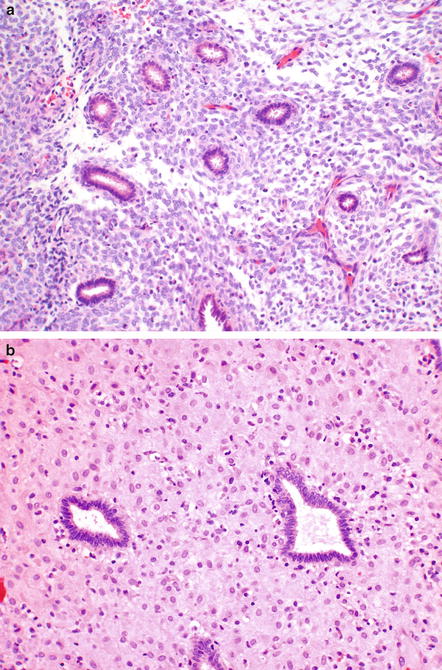

Chronic endometritis may be caused by identifiable organisms such as actinomyces or tuberculosis; however, an etiology is usually not apparent. Chronic endometritis may be associated with IUD use, history of instrumentation, submucous leiomyomata, or retained placenta, but often it is unclear what the underlying etiology is. It is debated in the literature whether the histologic finding of chronic endometritis corresponds to abnormal uterine bleeding, or is just an incidental finding. Histologically, chronic endometritis is diagnosed when plasma cells are seen in the endometrium (Fig. 6.2a). A hypercellular or spindled stroma (Fig. 6.2b) suggests that plasma cells should be sought. Other types of inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, neutrophils) are present physiologically during the menstrual cycle and do not indicate chronic endometritis.

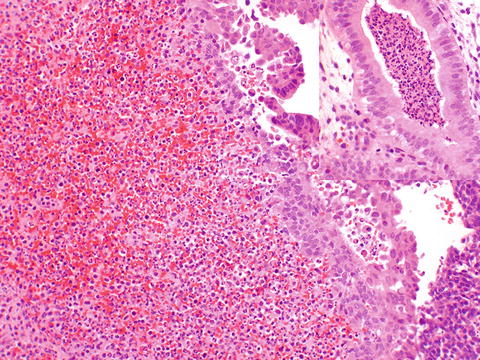

Fig. 6.2

Chronic endometritis is assessed by identifying plasma cells in the stroma (a, arrows). A spindled cell (b) or hypercellular stroma is a clue that plasma cells should be sought

6.3 Exogenous Hormones

Exogenous hormones exert varying influences on the endometrium. Age and hormonal milieu of the patient as well as the type of drug and duration of use influence the findings, so it is important to provide a clinical history, so that appropriate correlation can be made [1]. It should be remembered that endogenous hormones also may affect the endometrium, such as an estrogen-producing granulosa cell tumor, and these neoplasms should also be considered in clinically appropriate situations.

6.3.1 Oral Contraceptives and Progestins

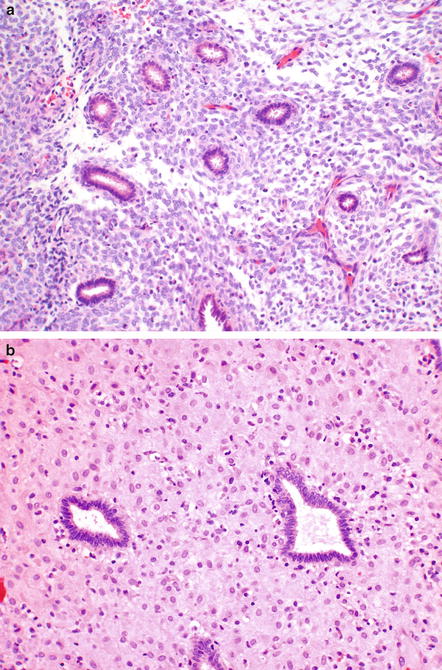

Histologic manifestations of oral contraceptives on the endometrium relate to the progestin-dominant effects. Early on in administration, the stroma appears spindled, and the glands become small and inactive (Fig. 6.3a). Over time, the stroma becomes decidualized. It is this combination of decidualized stroma and tiny inactive glands that confirms exogenous progestin exposure. Progestins used therapeutically for abnormal bleeding usually show stromal decidualization directly, without a spindle cell stromal phase (Fig. 6.3b).

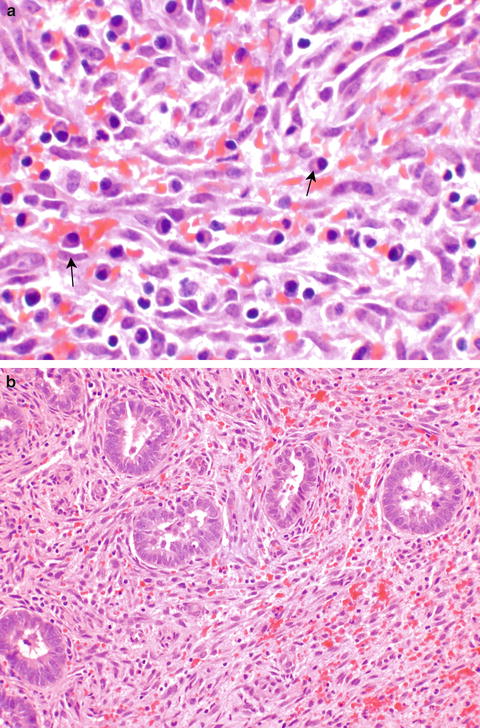

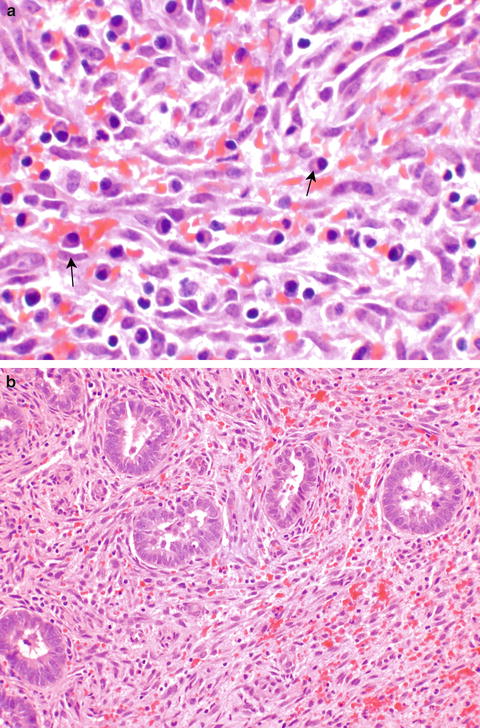

Fig. 6.3

Oral contraceptive pills affect the endometrium by leading to small inactive glands. Initially the stroma is spindled (a). Later, the stroma is decidualized (b) and appears similar to progestational therapy

6.3.2 Hormone Replacement Therapy

Hormone replacement comes in many combinations, so there is no one finding. In general, the effects tend to be a mix of estrogenic and progestational, hence a mix of proliferative and secretory changes may be seen. This “confused” endometrium does not appear neoplastic, but doesn’t fit textbook categorization. A history provided to the pathologist will lead to a shorter more comprehensible diagnosis (see Table 6.1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree