(1)

Department of Pathology, Rutgers-New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ, USA

Keywords

Congenital anomalies of cervixCervicitisTransformation zoneNabothian cystEndocervical polypMicroglandular hyperplasiaEndometriosisLeiomyoma of cervixMesonephric remnantsCervical intraepithelial neoplasiaAdenocarcinoma-in-situ of cervixSquamous cell carcinoma of cervixSuperficially invasive carcinoma of cervix (SISSCA)Papillary squamotransitional carcinomaVerrucous carcinoma of cervixAdenocarcinoma of cervixAdenoma malignumAdenosquamous carcinoma of cervixGlassy cell carcinoma of cervixAdenoid basal carcinoma of cervix5.1 Lesims of the Cervix

Cervical biopsies and excisions are common specimens in the Pathology laboratory. Management depends heavily on a number of diagnostic features for individual lesions, and there are numerous pitfalls the clinician should be aware of (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1

Key points about cervical pathology

Biopsies obtained below the transformation zone may not detect neoplastic lesions |

LEEP introduces artifacts (cautery, fragmentation) that make evaluation of margins more difficult and sometimes not possible |

AIS cannot be reliably diagnosed on a punch biopsy, but requires at least a cone type of excision to assess all of the features |

Adjunct immunohistochemistry with p16 and Ki-67 is useful in distinguishing SIL from mimics |

5.2 Congenital Anomalies of the Cervix

The cervix is formed after fusion of the two Müllerian ducts and resorption of the septum. Anomalies are uncommon, but may include agenesis, dysgenesis, or duplication, generally in association with uterine duplication.

5.3 The Transformation Zone

The exocervix is lined by stratified squamous epithelium, normally non-keratinized, although keratinization may be seen with prolapse or HPV-related disease. The endocervix is lined by mucinous columnar epithelium. The meeting point of these two epithelial types is the squamocolumnar junction. This is not a static site, but moves over the course of a woman’s life. During early reproductive life, the squamocolumnar junction is easily seen on the portio vaginalis. This led in the past to the mistaken diagnoses of “erosion” or “ectropion,” due to the red beefy appearance of the columnar epithelium. The squamocolumnar junction moves cranially over a woman’s life, with the location high up in the endocervical canal after menopause, making an adequate colposcopy requiring visualization of the entire transformation zone more difficult. The advancing squamocolumnar junction occurs by advancing squamous metaplasia replacing glandular epithelium. The metaplastic squamous epithelium is an immature squamous epithelium that matures and acquires glycogen over time. This metaplastic squamous epithelium spreads over the surface and into endocervical crypts. The zone between the original squamocolumnar junction and the woman’s current squamocolumnar junction is called the transformation zone (see Chap. 2). This is where cervical neoplasia occurs, and if a biopsy is too low, doesn’t sample the transformation zone, as evidenced by the presence of either both epithelial types, or metaplastic squamous epithelium, a neoplastic lesion has not been ruled out.

5.4 Infections and Inflammations of the Cervix

A degree of chronic inflammation is seen in most cervices in hysterectomy specimens and is not pathologic. Gonorrhea and Chlamydia may lead to a mucopurulent cervicitis. Follicular cervicitis, with formation of lymphoid follicular centers, may sometimes be associated with chlamydia [1], but is not a reliable diagnostic finding. The cervix may be involved by other infections such as herpes, or rarely by tuberculosis.

5.5 Benign Lesions of the Cervix

5.5.1 Nabothian Cysts

During the process of squamous metaplasia as the squamocolumnar junction advances, the endocervical crypts may become blocked, with inspissated mucus. Grossly these appear as blue-domed Nabothian cysts. Histologically, they appear as dilated glands lined by mucinous columnar epithelium (Fig. 5.1).

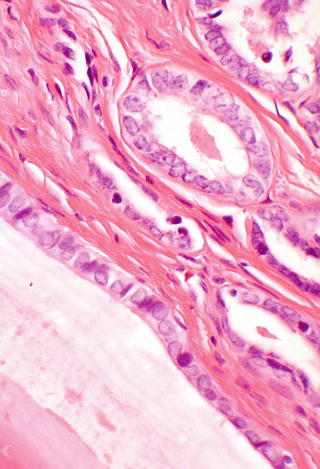

Fig. 5.1

Nabothian cyst. Dilated endocervical gland covered by surface squamous epithelium

5.5.2 Endocervical Polyps

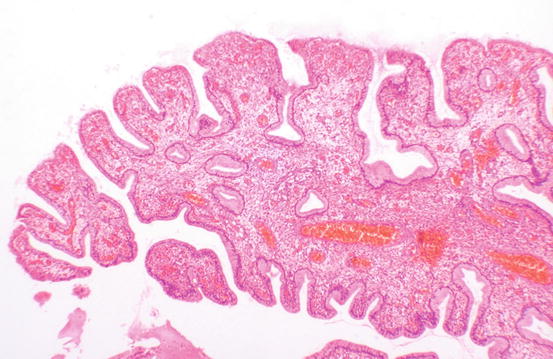

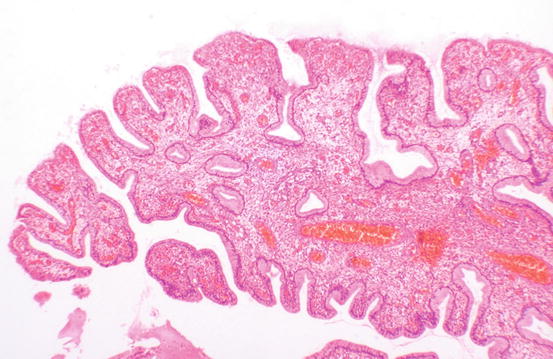

Endocervical polyps are common. They are polypoid lesions composed of endocervical epithelial-lined glands and crypts lining a fibroconnective tissue polyp containing prominent stalk vessels (Fig. 5.2).

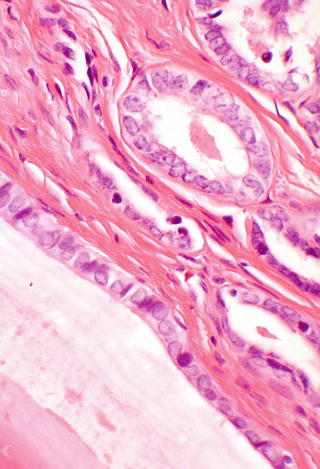

Fig. 5.2

Endocervical polyp. These lesions are lined by mucinous columnar epithelium. Squamous metaplasia is sometimes present. Inflammation is common

5.5.3 Microglandular Hyperplasia

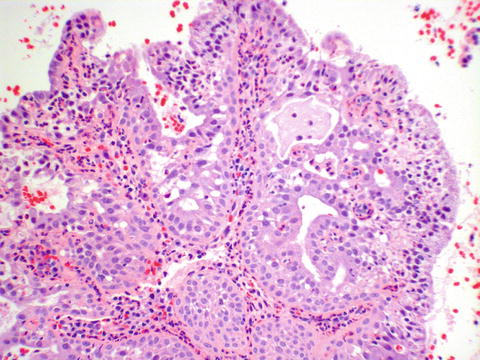

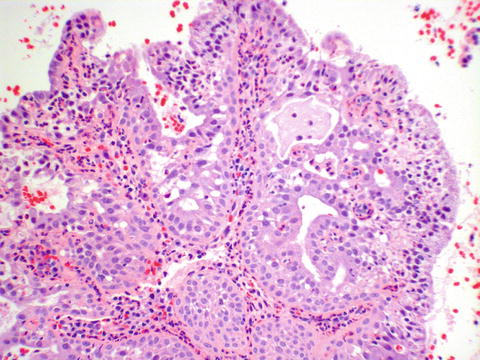

Microglandular hyperplasia is a benign lesion thought to be associated with progestational exposure, such as oral contraceptives or pregnancy. It is of no clinical significance. Histologically, the crowded glands may be mistaken for adenocarcinoma; however, there is no significant atypia, and there is generally a prominent acute inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 5.3).

Fig. 5.3

Microglandular hyperplasia characterized by crowded glands without atypia, squamous metaplasia, and acute inflammation with many neutrophils

5.5.4 Endometriosis

Endometriosis may affect the cervix, where it can appear as purple-blue lesions. Histologically, endometrial glandular epithelium and stroma must be present to confirm the diagnosis, as in other locations.

5.5.5 Leiomyoma

Cervical leiomyomas are histologically similar to the uterine counterpart and are most notable clinically for mechanical issues.

5.5.6 Mesonephric Remnants

Mesonephric remnants are commonly seen in hysterectomy specimens if looked for. These Wolffian duct remnants reside in the lateral aspects of the cervix and are composed of tubules lined by a cuboidal epithelium, often with inspissated eosinophilic secretions (Fig. 5.4). Rarely, these remnants may become hyperplastic or even give rise to carcinoma.

Fig. 5.4

Mesonephric remnants, lined by cuboidal epithelium and containing eosinophilic secretions

5.6 Preinvasive Neoplasia of the Cervix

5.6.1 Cervical Squamous Intraepithelial Neoplasia

Preinvasive squamous neoplasia is associated with human papillomavirus (HPV). For low-grade lesions, many regress or remain stable. The risk of progression is greater with high-grade lesions. It is important to sample the transformation zone when performing cervical biopsies, in order to obtain the lesion reliably. Positive endocervical curettings may mean that a lesion is up in the canal, but dysplastic squamous epithelium is friable, and fragments from the exocervix can break off during instrumentation and get into the endocervical curetting specimen. For cone biopsies, it is important for clinicians to be aware that LEEP cone biopsies are more difficult to evaluate margins on. This relates to cautery artifact, as well as potentially to tissue fragmentation, particularly if more than one pass is performed. Hence, cold knife cone may be preferable for cases where assessment of the margins is critical.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree