Fig. 32.1

Clinical presentation of the maculopapular rash after 2 weeks of therapy with vemurafenib (Courtesy of Rinderknecht et al. (2013))

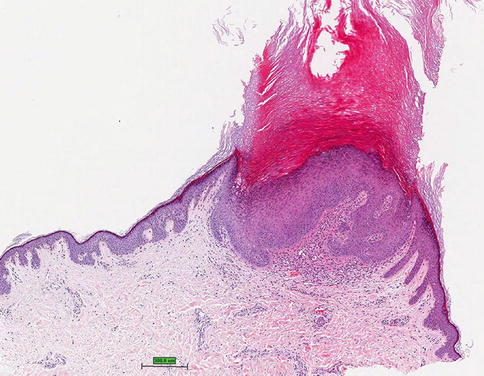

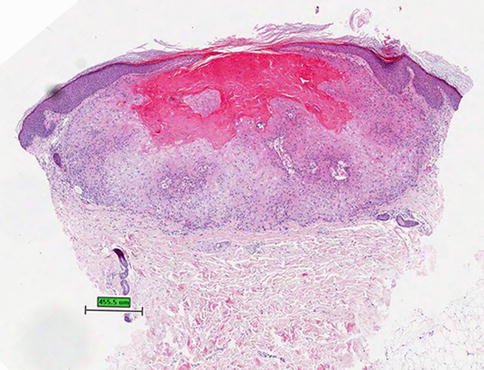

Fig. 32.2

Histology of the maculopapular rash demonstrates a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with interface changes, hematoxylin and eosin stain (Courtesy of Rinderknecht et al. (2013))

Grover’s disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis) is a benign acantholytic disorder. It presents as several scattered erythematous papules, some eroded, with or without crusting. It typically affects the extremities and trunk, and is usually asymptomatic or only slightly pruritic. It has been reported in up to 27 % of patients receiving dabrafenib, and is similar to idiopathic Grover’s disease both clinically and histologically. Median time to presentation in one study of patients on dabrafenib was 79 days. Grover’s disease and eruptions resembling Darier’s disease have been seen in patients taking vemurafenib, as well.

Dry Skin

Xerosis has been reported to occur in 14–33 % of patients receiving vemurafenib. Mean time to onset was 57 days in one study. The xerosis was sometimes associated with mild pruritus.

Hair Follicle Changes

Several changes affecting the hair follicle have been reported with the type 1 BRAF inhibitors, including slower and thinner growth of scalp hair (up to 29 %), alopecia (8–36 %), changes in the structure of the hair (i.e., from straight to curly, 17 %), folliculitis (9 %), and keratosis pilaris. Dabrafenib has also been associated with a change in the color (turned grey) of hair during treatment, but this has not been reported with vemurafenib. Interestingly, the alopecia has been reported to spontaneously reverse despite continued treatment.

Both vemurafenib and dabrafenib have been associated with keratosis pilaris-like eruptions and folliculocentric erythematous exanthems. In a study on vemurafenib, 43 % (12/28) of patients developed disseminated small hyperkeratotic follicular papules consistent with keratosis pilaris. This occurred often on the face, proximal upper, or lower extremities and was observed more frequently at early treatment time points. In other studies, a follicular eruption was described in 18–55 % of the patients.

Milia have been seen in 31 % of patients on vemurafenib, and occurred after a mean time to onset of 48 days in one study. Epidermoid cysts have been reported to occur in 33 % of patients, with a mean time to onset of 108 days in the same study. In a dabrafenib study, 20 % of patients developed epidermal cysts, usually small milia type, on the face, and less frequently on the trunk. Seven percent developed acneiform lesions on the face and trunk.

Nail Changes

Crumbly nails and nail color changes were encountered in 7 % (2/28) after 2 weeks and 6 weeks, respectively, of treatment with vemurafenib in one study.

Hyperkeratosis

Hyperkeratosis has been reported with both vemurafenib and dabrafenib (6–51 %). Common hyperkeratotic lesions described include verruca vulgaris, seborrheic keratoses, and plantar and palmar hyperkeratosis. A universal clinicohistopathological classification of keratotic lesions induced by BRAF inhibitors is needed to ensure consistent nomenclature and accurate comparisons between BRAF inhibitors.

Plantar hyperkeratosis (Fig. 32.3) has been reported with use of vemurafenib (9–60 %) and dabrafenib (8–22 %). The hyperkeratosis typically presents as yellowish, painful, hyperkeratotic plaques localized to the pressure points on the sole of the foot (i.e., heels and metatarsals). Unlike hand–foot skin reaction reported in patients receiving sorafenib, or palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome seen with some chemotherapy, patients on type 1 BRAF inhibitors present with lesions only at points of pressure or friction, blisters are infrequent, and the hands are seldom involved.

Fig. 32.3

Plantar hyperkeratosis developed after 4 weeks of therapy with vemurafenib (Courtesy of Rinderknecht et al. (2013))

Squamoproliferative Lesions

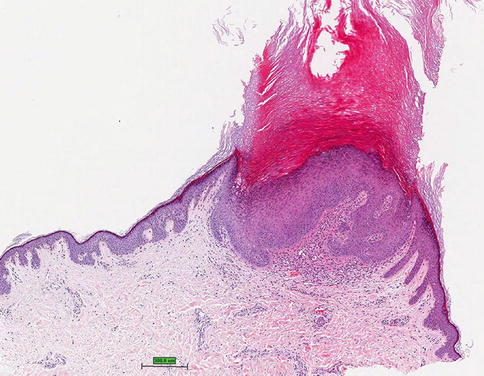

Skin papillomas are benign acanthotic lesions without signs of malignancy and have been reported in 15–46 % of patients treated with vemurafenib. They have been reported on the head, neck, and trunk. Histological evaluation of these lesions revealed marked hyperkeratosis and acanthosis and hypergranulosis, koilocytes, mitosis, and arborization of the peripheral rete ridges, suggesting viral association (Fig. 32.4). Consistent clinicohistopathological classification of skin papillomas induced by BRAF inhibitors is needed for accurate comparisons between studies.

Fig. 32.4

Acanthopapilloma with marked hyperkeratosis and acanthosis, hematoxylin and eosin stain (Courtesy of Rinderknecht et al. (2013))

Verruca vulgaris has been reported in 46.7 % of patients treated with vemurafenib and 5 % of patients on dabrafenib. Seborrheic keratoses were found to occur in 34 % of patients on dabrafenib. In dabrafenib trials, hyperkeratotic actinic keratoses have been noted in 10 % of patients. In a retrospective review of 15 patients treated with vemurafenib, 6 (40 %) developed actinic keratoses.

Verrucal keratoses are hyperkeratotic papules clinically similar to keratocanthomas (Fig. 32.5), warts, or nonspecific hyperkeratotic papules. Histologically, they demonstrate papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, preserved granular cell layer, and various degrees of epidermal dysplasia (most commonly mild to moderate atypia) with absence of koilocytes and keratohyaline granules. Verrucal keratoses have been reported to occur on both sun-damaged and non-sun-damaged skin in various anatomical locations in up to 49 % of patients on BRAF inhibitors. Peak time to presentation is reported to be 6–12 weeks; however there does not appear to be a relationship between the length of time on treatment and the appearance of these lesions or the degree of atypia. These lesions have not been shown to be malignant, but the noted variation in epidermal dysplasia could suggest they are premalignant variants of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas.

Fig. 32.5

Clinical picture of the kerathoacanthoma, appeared after 5 weeks of treatment with vemurafenib (Courtesy of Rinderknecht et al. (2013))

Squamous Cell Carcinomas

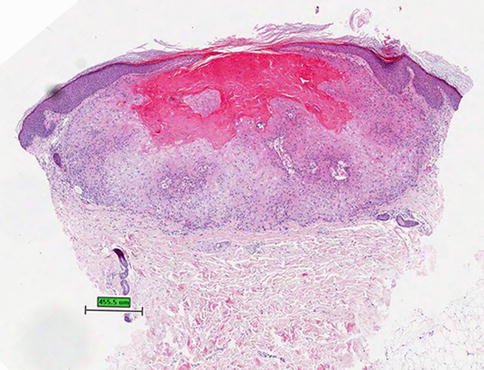

The most common malignant tumor documented in melanoma patients receiving BRAF inhibitors is cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) (Fig. 32.6), reported in 4–31 % of patients receiving vemurafenib and 6–20 % of patients given dabrafenib. These cutaneous SCCs are typically well differentiated or keratoacanthoma-type, however a few less well-differentiated SCCs have been reported. The cutaneous SCCs associated with use of type 1 BRAF inhibitors have occurred on both sun-exposed and non-sun-exposed skin. The median time to first incidence of cutaneous SCC was 8 weeks in vemurafenib and 16 weeks in dabrafenib. In a prospective study of patients taking dabrafenib, SCCs were located on the upper arm, chest, back and/or thigh in 67 %; and on the head, neck, forearm, hand and/or lower leg in 33 %. This is in contrast to the locations commonly seen for cutaneous SCCs. In the same study, 88 % of patients who developed a SCC also developed a verrucal keratosis, suggesting a relationship between verrucal keratosis and SCC development.

Fig. 32.6

Invagination of keratinizing, squamous epithelium with central keratin-filled crater characterizing a keratoacanthoma, hematoxylin and eosin stain (Courtesy of Rinderknecht et al. (2013))

Well-differentiated and keratoacanthoma-type cutaneous SCCs were also reported in 8 % of 48 patients enrolled in the phase 1 study of XL281 (now BMS908662), a RAF inhibitor of unknown type, and in all three patients with melanoma given BMS908662 combined with ipilimumab.

Cutaneous SCCs have been treated with excision, and dose adjustment of vemurafenib and dabrafenib has not been necessary for management of cutaneous SCC in any of the studies thus far. No metastasis of cutaneous SCC has yet been reported with use of the type 1 BRAF inhibitors. In a prospective study of dabrafenib, most SCCs were detected between weeks 6 and 24 of treatment, suggesting that close monitoring in the first 6 months of treatment is important.

Melanocytic Nevi and Melanoma

New melanocytic nevi and new primary melanomas (Figs. 32.7 and 32.8) have been noted in patients receiving BRAF inhibitors. New primary melanomas were reported in the phase 3 trials of vemurafenib (in 8 of 337 patients) and dabrafenib (3 of 187). Many studies and reports note that the new primary melanomas appearing in patients receiving BRAF inhibitors, although in a small number of patients, are wild-type BRAF lesions. BRAF wild-type melanomas might develop during BRAF blockade as a result of BRAF inhibitor-induced tumor progression via the stimulation of MAPK signaling.