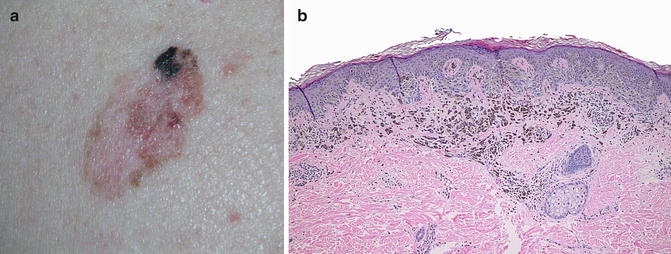

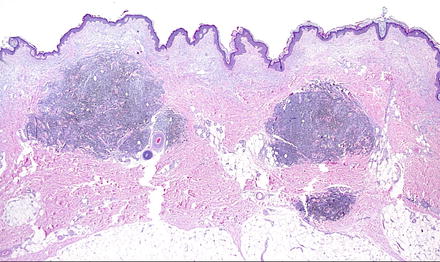

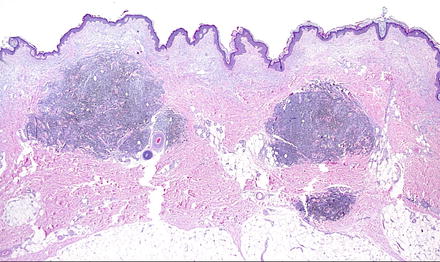

Fig. 15.1

Nodular malignant melanoma with an adjacent associated nevus

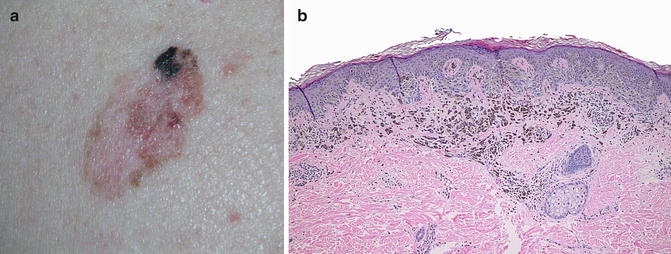

Another criterion favoring the interpretation of a primary rather than metastatic melanoma is the presence of regressive features, including an inflammatory infiltrate composed predominately of T-lymphocytes and plasma cells, melanophages, lamellar fibroplasia, and vascular proliferation [Fig. 15.2]. Complete regression of primary cutaneous melanoma is uncommon, occurring in 2.4–8.7 % of cases, while partial regression has been reported in 10–35 % of cases [5]. Evidence of spontaneous regression of metastatic melanoma is present in only 0.23 % of cases [6]. Regression is an immune-mediated phenomenon in which the patient’s T-cells recognize antigens on certain clones of the tumor cells while other clones go unrecognized. It is thought that these surviving clones are more prone to metastasize to distant sites where they will continue to evade the immune response, explaining the low incidence of spontaneous regression of metastatic lesions [5, 6]. This theory is supported by the fact that in-transit metastases are clonal in origin [7].

Fig. 15.2

(a) Primary melanoma with partial regression, seen grossly as an area of depigmentation within the melanoma; (b) Microscopic features of partial regression are seen here including the presence of a lymphocytic infiltrate, melanophages, and fibrosis

Probably the most important histopathologic feature favoring that a cutaneous melanoma is a primary and not a metastatic lesion is the presence of an intraepidermal (in situ) component, especially one extending beyond the lateral edge of the dermal component. However, even in some primary melanomas it can be difficult or even impossible to identify a definitive in situ lesion; this situation may arise due to sampling error, ulceration, regression, or effects of previous biopsy. If no in situ component can be identified, it is best to raise the possibility that the lesion could represent a metastasis.

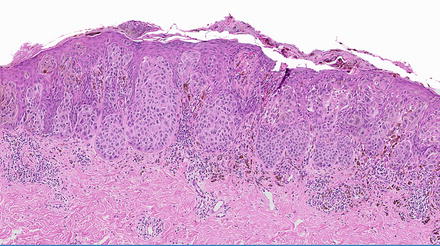

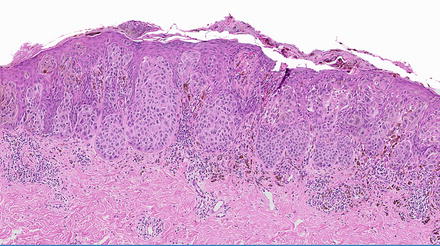

To add a further complication, rare cases of epidermotropic metastatic malignant melanoma (EMMM) closely mimic primary melanoma. The histopathologic criteria originally proposed in 1978 for distinguishing EMMM from primary melanoma included the presence of an epidermal collarette; a dermal component extending beyond the intraepidermal component; and invasion of the lymphovascular space [8]. However, subsequently many cases of EMMM have been reported in which these criteria were not met and it has become clear that no set of histopathologic criteria can consistently discriminate between EMMM and primary melanoma. EMMM can even in some cases be completely confined to the epidermis, simulating an in situ melanoma [Fig. 15.3]. In such cases, histopathologic clues to the diagnosis of EMMM include relatively small size, symmetry, extensive pagetoid spread, and involvement of the adnexal epithelium. When a dermal component is also present, angiotropism is a strong indicator of metastatic disease [9].

Fig. 15.3

Epidermotropic metastatic melanoma with prominent pagetoid spread mimicking a primary cutaneous melanoma

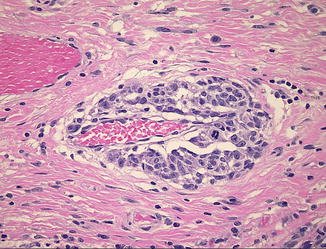

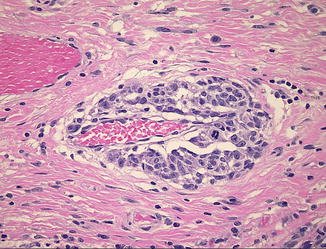

Cutaneous melanoma metastasis classically presents as a well-circumscribed dermal or subcutaneous nodule of atypical, mitotically active melanocytes [Fig. 15.4]. Additional histopathologic characteristics in favor of cutaneous melanoma metastasis include a lack of involvement of the epidermis and absence of an inflammatory response. Metastatic lesions are more likely than primary tumors to be monomorphic [10], reflecting the frequent clonality of metastatic melanoma tumors [7]. The presence of angiotropism (melanoma tumor cells surrounding the external surface of vessels) and lymphatic invasion also supports a diagnosis of metastatic melanoma [9] [Fig. 15.5].

Fig. 15.4

Multiple nodules of cutaneous metastatic melanoma are seen here in the dermis

Fig. 15.5

Angiotropic spread of melanoma cells around a dermal blood vessel

Another diagnostic dilemma comes into play when the lesion in question is within or adjacent to the scar of a previously excised primary melanoma. In this instance it can be difficult to determine whether one is dealing with an EMMM or a recurrence from residual primary melanoma that was incompletely excised. Interestingly, recurrent melanoma arising within an excision scar has the same prognosis as melanoma with nodal metastasis, suggesting that many such cases may actually be metastatic lesions [9]. Histopathologically, a clue to recognizing cutaneous metastatic melanoma is the pattern of infiltration of the scar by small groups, strands, and individual melanoma cells.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree