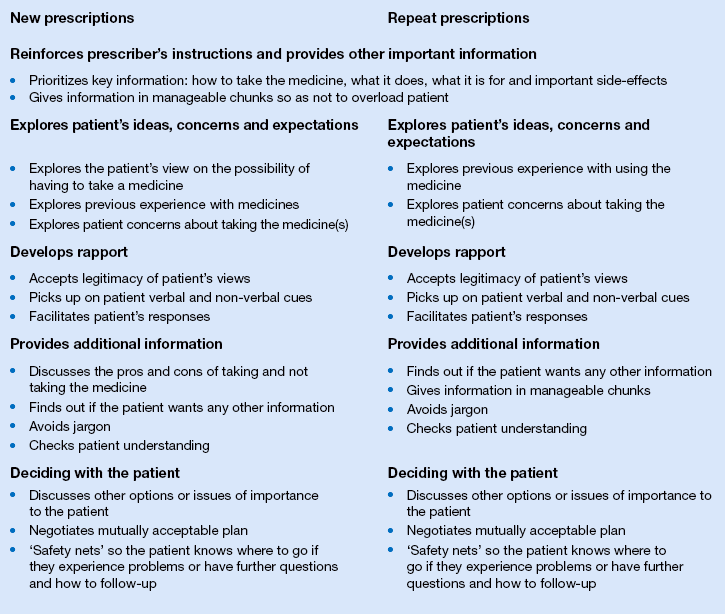

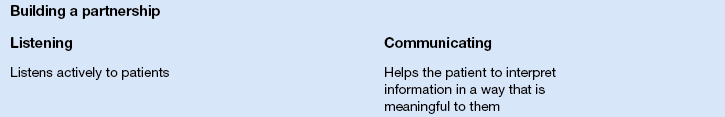

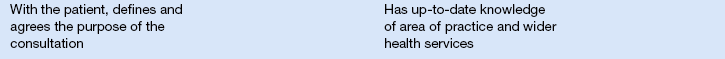

18 ‘Mrs Jones is being a non-concordant patient [sigh] again’. Or is she? Concordance offers a way forward when we, as pharmacists, notice that patients are not taking their medicines as prescribed. Yet concordance can fundamentally challenge our assumptions about the role of patients in a professional–patient interaction. It states that patients have a legitimate and valuable perspective on taking their medicines and that healthcare professionals should encourage patients, should they wish it, to become involved in decisions about their treatment. For these reasons, concordance is about a consultation process and not individual patient behaviour. Mrs Jones cannot be non-concordant on her own: it takes at least two, professional and patient, to have a non-concordant (or successfully concordant) encounter. The consultation could have been non-concordant but Mrs Jones, on her own, cannot have been. Mrs Jones can be non-compliant or non-adherent with her medicine but these have a distinctly different meaning from concordance. This is not to say that terms like adherence and compliance can no longer be used. When referring to the extent to which patients take medicines as prescribed by their doctor or other healthcare professional, the words ‘adherence’ and ‘compliance’ are appropriate terms to be used. As a concept distinct from compliance or adherence, concordance may affect adherence although it is mainly concerned with improving the quality of health care through a shared understanding between professional and patient on treatment choices. Yet there are difficulties with words like adherence and compliance, which have overtones of the patient being disobedient or ‘naughty’ in not following the doctor’s instructions. Conceptually, terms like ‘compliance’ and ‘adherence’ reinforce a paternalistic doctor-knows-best model of health care and implicitly devalue the views and experience of patients as users of medicines. Concordance seeks to redress this balance by acknowledging that patients and customers have a key role in the decision-making of whether or not to take their medicine. Concordance shares many features with the formative communication teaching guides, the Calgary–Cambridge guides as discussed in Chapter 17. Although designed as a formative aid in teaching medical students communication skills, the Calgary–Cambridge guides have a consultation structure which is readily adaptable to the pharmacy setting. These guides assume a chronology to the consultation with distinct sections on initiating the consultation, gathering information, providing structure to the consultation, building a relationship, explanation and planning and closing the consultation. The Calgary–Cambridge guide has been adapted to reflect two common pharmacy consultation situations of (1) handing out a new prescription and (2) issuing a repeat prescription, as shown in Box 18.1. Sample phrases or ‘catchphrases’ useful in conducting a concordant consultation in pharmacy are shown in Box 18.2. The Medicines Partnership at NICE has developed a competency framework for shared decision-making with patients, describing the skills and behaviours professionals need to reach a shared agreement about treatment. In this document, shared decision-making and concordance are used synonymously, highlighting the common approach underpinning these concepts. These eight competencies are shown in Box 18.3. Already presented has been the Haynes Cochrane review regarding the use of interventions to help patients take their medicines; that current methods of improving adherence are complex and not very effective. Much of the information available about concordance relates to the doctor–patient consultation. As shown in Box 18.1, the concordant approach can be readily adapted to the pharmacy situation after a prescribing decision has been made. Examples are handing out new or repeat prescriptions, in repeat dispensing or in conducting a medicines use review. Yet pharmacists also have a role before treatment decisions about medicines are made: when giving over-the-counter advice or as pharmacist independent prescribers. The next sections will look at this evidence, drawing upon pharmacy literature where possible, as well as evidence from medicine. Medical literature may appear to be relevant only in the latter situation, i.e. before prescribing decisions are made. However, the evidence has resonance for the range of pharmacy consultations, both before and after treatment decisions have been made. These are grouped under four headings: eliciting the patient’s view; developing rapport with the patient; providing information; and the therapeutic alliance.

Concordance

What is meant and understood by the term ‘concordance’

What is meant and understood by the term ‘concordance’

How concordance differs from compliance and adherence

How concordance differs from compliance and adherence

The concordance model and the relationship with patients

The concordance model and the relationship with patients

The need for good communication skills in developing a concordant relationship

The need for good communication skills in developing a concordant relationship

Introduction

What is concordance?

They have experienced side-effects

They have experienced side-effects

Taking medicines interferes with their daily lives

Taking medicines interferes with their daily lives

They have beliefs about the medicines or illness which conflict with medicine taking

They have beliefs about the medicines or illness which conflict with medicine taking

They are adjusting the medicine dose in response to symptoms.

They are adjusting the medicine dose in response to symptoms.

The concordance model

The evidence for concordance

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree