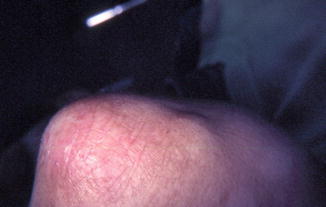

Fig. 16.1

Annular plaque on the breast of a woman who was on methyldopa. The biopsy was compatible with DLE. The patient was histone positive and improved when the drug was stopped

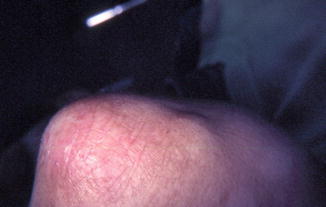

Fig. 16.2

Photodistributed oval erythematous plaques that were sun-induced in a patient on hydrochlorthiazide. She was SSA/SSB positive. The biopsy was compatible with subacute cutaneous lupus, and the patient cleared when the drug was discontinued

Drug-Induced SCLE

SCLE is an autoimmune disease that is more likely to occur among genetically predisposed individuals confronted with an environmental trigger. The inherited antigens correlating most with SCLE include human leukocyte antigen (HLA) B8, HLA-DR3, HLA-DRw52, and HLA-DQ1. Individuals with anti-Ro (SS-A) or anti-La (SS-B) autoantibodies are greatly predisposed to developing SCLE, as greater than 80 % of those with SCLE are anti-Ro antibody positive. A positive anti-histone antibody is indicative of drug induced LE.

Environmental triggers commonly involve ultraviolet light, which supports the observation that lesions are most frequently distributed on sun-exposed surfaces of the body. The exact mechanism is unknown. However, approximately 30 % of patients with SCLE are found to have a drug as the inciting agent. Drugs can either induce or exacerbate the disease. In particular, the anti-hypertensive, hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), has been extensively studied and is most frequently noted for its temporal relationship to drug-eruptions causing SCLE, as well as remission of disease when the agent is discontinued. Other drugs demonstrating a strong association with drug-induced SCLE include, but are not limited to, other antihypertensive medications, especially calcium channel blockers (CCB) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I), D-penicillamine, anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, the antifungals griseofulvin and terbinafine, anti-epileptics, and proton-pump inhibitors (Table 16.1).

Table 16.1

Drugs reported to induce subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Anti-arrhythmics/anti-hypertensives ACE inhibitors Enalapril Lisinopril Captopril Cilazapril Ramipril β-blockers Oxprenolol Acebutolol Calcium-channel blockers Diltiazem Verapamil Nifedipine Nitrendipine Class I anti-arrhythmics Quinidine | Antibiotics/antifungals Griseofulvin Terbinafine Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | Anti-cholinergics Inhaled tiotropium |

Antidepressants Buproprion | Anti-epileptics Carbamazepine Lamotrigine Phenytoin | Anti-gout agents Allopurinol |

Antihistamines Ranitidine Brompheniramine Cinnarizine + thiethylperazine | Anti-neoplastics Docetaxel Paclitaxel Tamoxifen Capecitabine Doxorubicin Methotrexate | Anti-thombotics Ticlopidine |

Biologics Adalimumab Bevacizumab Etanercept Efalizumab Golimumab Infliximab | Diuretics HCTZ HCTZ + triamterene Chlorothiazide | Glucose control Glyburide |

Hormone-modulators Leuprorelin Anastrazole | Immunomodulators Leflunomide Interferon alpha and beta 1a | NSAIDs Piroxicam – |

Proton-pump inhibitors Lansoprazole Pantoprazole Omeprazole | Statins Simvastatin – | Other D-penicillamine (chelator, rheumatoid treatment) |

Studies have aimed to determine the time interval between drug exposure and cutaneous eruption (incubation time), as well as the time interval between drug discontinuation and resolution of cutaneous eruption (resolution phase). The incubation period between drug exposure and appearance of drug eruptions varied greatly between drugs and depended heavily on drug classes. A study published by G. Lowe in the British Journal of Dermatology demonstrated a mean incubation period of approximately 28 weeks. In the same study, thiazide diuretics, such as HCTZ, and calcium channel blockers (CCBs), such as verapamil and diltiazem, proved to have the largest interval of incubation, whereas antifungal medications had the shortest incubation period. The incubation period for thiazides and calcium channel blockers varied greatly, from months to years. The mean incubation time for antifungal medication was approximately 1 month. These varying incubation times emphasize the need to consider historical drug exposures as well as drugs that were started without incident when diagnosing current dermatologic findings.

Diagnosis

SCLE is a diagnosis based on clinical presentation, in conjunction with results from histopathology, immunofluorescence, and serology. Notably, drug-induced SCLE may differ from idiopathic SCLE in that drug-induced SCLE are more likely to cause malar rash accompanied by bullous erythema multiforme and vasculitic manifestations. In SCLE, histology reveals a thin epidermis, with slight lymphocytic perivascular and perifollicular inflammatory infiltrate in the superficial and deep dermis. Follicular plugging, hyper-orthokeratosis, and parakeratosis are less common than with other forms of lupus erythematosus, such as discoid lupus. The epidermis in SCLE lesions displays extensive damage of all layers, with eosinophilic necrosis and vacuolization. The majority of patients have a positive immunopathologic lupus band test, meaning that complement and or immunoglobulin is present along the dermal-epidermal junction. Serology in SCLE is often positive for ANA and is more likely than SLE to be associated with positive SS-A and SS-B autoantibodies. Anti-histone antibodies are present in more than 95 % of cases of drug-induced SCLE.

Treatment and Course

The average resolution time upon discontinuing the inciting drug is approximately 7 weeks. Several studies attempted treatment before discontinuing the drug, with no resolution noted until the drug was eventually terminated. Most lesions resolve without additional treatment. However, a few reported cases in the literature have required active treatment for resolution of drug-induced SCLE to occur; the inciting drugs in these cases were terbinafine, leflunomide, anastrazole, leuprorelin, and psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy. Treatment was initiated with topical steroids such as clobetasol, oral prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, topical tacrolimus, or mycophenolate mofetil. In several follow-up appointments, most patients who were originally anti–Ro or La positive did not convert to negative upon resolution. This signified that once a patient seroconverted, he or she remained positive for the antibodies associated with the disease despite treatment and resolution of symptoms.

Drug-Induced Lupus Erythematosus (DILE)

Drug-induced lupus erythematosus (DILE) can be easily confused with drug-induced SCLE; however, the key distinction is that whereas both conditions are drug-induced, SCLE is primarily cutaneous. While DILE can be cutaneous as well, it is more likely than SCLE to manifest systemically. Malar and discoid lesions are rare in DILE, as are renal or neurologic impairments. In addition, DILE has a distinct antibody profile from traditional SLE and SCLE. While both SCLE and DILE (as well as SLE) are associated with a positive ANA and anti-histone antibodies, SCLE patients are far more likely to be Anti-Ro (SS-A) or anti-La (SS-B) positive. DILE patients are more likely to have a homogenous pattern of anti-histone antibodies on immunopathology, whereas drug-induced SCLE patients most often have a speckled pattern. DILE usually has normal complement levels, whereas SCLE can be associated with complement deficiency. The inciting drugs also differ, with DILE more likely to be caused by procainamide, isoniazid, timolol, and hydralyzine.

Dermatomyositis (DM)

Dermatomyositis (DM) is a CVD that is distinguished by characteristic skin lesions and myopathy. The myopathy is usually inflammatory and can cause weakness. The skin lesions considered diagnostic of DM consist of varying forms of dermatitis and an eyelid heliotrope rash with periorbital edema, although a host of cutaneous named signs are also associated with DM. Idiopathic DM can involve a vague systemic prodrome, edema, dermatitis, interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, and inflammation of muscle tissue. The prodrome is typically characterized by intermittent fevers, malaise, anorexia, arthralgias, and marked weight loss. The muscle involvement is primarily proximal, resulting in myalgias and muscular degeneration. DM is relatively rare, and like most autoimmune diseases affects mostly women. African Americans are disproportionately affected. Although adults can be affected, there is a juvenile form of DM as well. The drugs most known to cause DM are hydroxyurea and D-penacillamine.

Clinical Presentation

Some pathognomonic skin findings of DM are the heliotrope rash, Gottron’s papules, mechanic’s hands (Fig. 16.3), Holster shawl, V-signs, and malar rash. The heliotrope rash (named for the purple flower) is described as an erythematous to violaceous eruption around the upper eyelids associated with swelling. The heliotrope rash is often tender to touch as it can involve the orbicularis oculi muscle. Gottron’s papules consist of erythematous to violaceous papules that erupt symmetrically along the extensor surfaces of the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints (Fig. 16.4), although the term is sometimes used to refer to similar lesions on the medial malleoli. The papules can become scaly and ulcerate. Mechanic’s hands are hands whose palms and lateral finger surfaces are thickened (hyperkeratotic). Holster sign signifies similar lesions on the hips, shawl sign is erythema of the upper back and shoulders, and V-sign is erythema of the V-area of the neck and chest. Holster sign is significant for the fact that it is outside of the typical photodistributed pattern of presentation. Poikiloderma—hyperpigmented and hypopigmented lesions that contain small telangiectasias with epidermal atrophy—may be observed along with erythema in the areas of the shawl and V-signs. The lesions are typically quite pruritic and may become thickened and palpable. Facial erythema can also be present and is similar to the characteristic malar rash of SLE; however the erythema involves the nasolabial skin folds that are typically spared in SLE and SCLE. Cuticle overgrowth and periungual changes may occur, particularly in the capillary nail beds. In addition, vascular changes can occur with areas of dilation presenting as erythematous changes elsewhere on the body.

Fig. 16.3

Mechanic’s hand with dermatitis along the radial edge of the index finger. It resolved when doxycycline was discontinued

Fig. 16.4

Hyperpigmentation and dermatitis over knuckles in a patient on minocycline mimicking dermatomyositis. Note also proximal nail fold changes

The “myositis” element of DM consists of symmetric proximal muscle weakness with edema and myalgias. The most common locations for these findings are the deltoids and hip flexors. Classic presentations and complaints are related to patients’ subsequent inability to climb stairs, comb their hair, or lift light objects over their heads. Involvement of bulbar muscles can cause difficulty swallowing, and potential involvement of respiratory muscles can make speaking and even breathing difficult. Finally, in the terminal phases of the illness, cardiac muscle involvement produces cardiac failure.

Drug-Induced DM

Many drugs have been reported to induce a DM-like eruption (Fig. 16.5). The agents most frequently implicated are hydroxyurea, penacillamine, and zoledronic acid, however other medications can cause the disease as well (Table 16.2). Case reports dominate the literature and review indicates that different drugs can induce different manifestations of DM. Humoral immunity and vasculopathy caused by complement deposition are most likely responsible for the muscular changes in DM. The causes of dermatologic findings are less clear, although it has been posited that the reaction is associated with the development of autoantibodies through the unmasking of sequestered antigens when the drug is introduced to bodily tissues.

Fig. 16.5

Erythema, atrophy, and telangiectasias over elbow in a patient on hydroxyurea, with symmetric dermatitis over the other elbow mimicking dermatomyositis

Table 16.2

Drugs reported to induce dermatomyositis

Antibiotics and anti-fungals | Isoniazid Penicillin Sulfonamides Terbinafine |

Anti-neoplastics | Capecitabine Cyclophosphamide Etoposide Hydroxyurea Tegafur |

Bisphosphonates | Zoledronic acid |

Chelators | Fibrates Statins |

Lipid-lowering agents | D-penicillamine |

Analgesics | NSAIDs |

Hydroxyurea

An antimetabolite agent that is most commonly used for the treatment of neoplastic myeloproliferative disorders. Other common uses for hydroxyurea include the treatment of sickle cell crises and chronic myelogenous leukemia, as well as adjunct therapy for autoimmune immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Many side effects can occur with the use of hydroxyurea, including several cutaneous reactions such as xerosis, ichthyosis, stomatitis, and DM-like eruptions. Several case reports have discussed hydroxyurea-induced DM, especially the appearance of Gottron’s papules. Notably, these DM-like cutaneous eruptions occur with or without the systemic manifestations typically found in the disease.

D-Penicillamine

Commonly used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, as it is an immunosuppressive agent that acts by reducing the number of T-cells and inhibiting macrophage functionality. It is also utilized as a copper chelator in the treatment of illnesses such as Wilson’s disease. A rare adverse effect found in several patients taking D-penicillamine for rheumatoid arthritis is the development of DM. Within 2 months of therapy with this agent, patients can begin to experience the classic heliotrope rash, Gottron’s papules, and erythema of the face, limbs, and chest.

Zoledronic Acid

A bisphosphonate commonly used for the treatment of osteoporosis, certain malignancies associated with fractures, as well as Paget’s disease, and there are case reports of it inducing DM. A case reported in the Australasian Journal of Dermatology in 2012 by Tong et al. identified a patient taking bisphosphonates for the treatment of her osteoporosis. Several days following a single infusion of zoledronic acid, the patient complained of proximal muscle weakness, fatigue, and a widespread rash on her forehead, neck, upper chest, lateral thighs, and left arm. The rash was reminiscent of DM: macular and violaceous with small telangiectasias.

Terbinafine

A commonly used allylamine antifungal medication effective against dermatophyte fungi. Topical preparations are available for superficial skin infections such as tinea, commonly known as ringworm. Oral preparations are used for the treatment of diseases such as onychomycosis, a fungal infection of the nail bed, because of the deeper location of the infection and minimal penetration of topical ointments. Several case reports indicate that terbinafine administration has a temporal relationship to dermatomyositis onset. Within several weeks of beginning oral terbinafine, a characteristic photodistributed erythema involving the face, neck, chest, abdomen, and extremities, as well as Gottron’s papules can erupt.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree