25

Chlamydiae

CHAPTER CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Chlamydiae are obligate intracellular bacteria (i.e., they can grow only within cells). They are the agents of common sexually transmitted diseases, such as urethritis and cervicitis, as well as other infections, such as pneumonia, psittacosis, trachoma, and lymphogranuloma venereum.

Diseases

Chlamydia trachomatis causes eye (conjunctivitis, trachoma), respiratory (pneumonia), and genital tract (urethritis, lymphogranuloma venereum) infections. C. trachomatis is the most common cause of sexually transmitted disease in the United States. Infection with C. trachomatis is also associated with Reiter’s syndrome, an autoimmune disease.

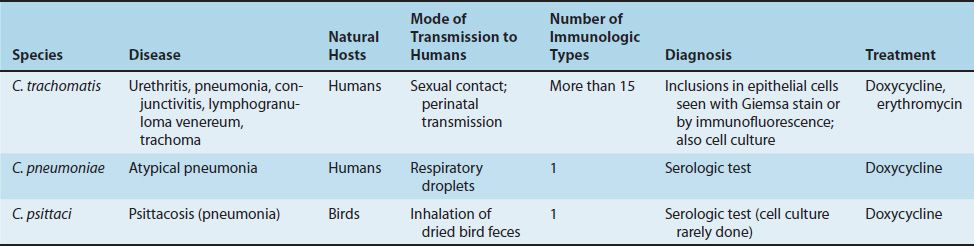

Chlamydia pneumoniae (formerly called the TWAR strain) causes atypical pneumonia. Chlamydia psittaci causes psittacosis (Table 25–1).

C. pneumoniae and C. psittaci are sufficiently different molecularly from C. trachomatis that they have been reclassified into a new genus called Chlamydophila. Taxonomically, they are now Chlamydophila pneumoniae and Chlamydophila psittaci. However, from a medical perspective, they are still known as Chlamydia pneumoniae and Chlamydia psittaci, and those are the names that are used in this book.

Important Properties

Chlamydiae are obligate intracellular bacteria. They lack the ability to produce sufficient energy to grow independently and therefore can grow only inside host cells. They have a rigid cell wall but do not have a typical peptidoglycan layer. Their cell walls resemble those of gram-negative bacteria but lack muramic acid.

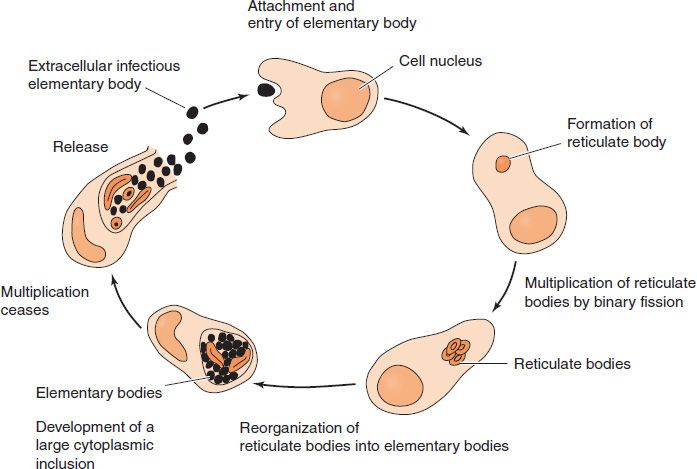

Chlamydiae have a replicative cycle different from that of all other bacteria. The cycle begins when the extracellular, metabolically inert, “sporelike” elementary body enters the cell and reorganizes into a larger, metabolically active reticulate body (Figure 25–1). The latter undergoes repeated cycles of binary fission to form daughter reticulate bodies, which then develop into elementary bodies, which are released from the cell. Within cells, the site of replication appears as an inclusion body, which can be stained and visualized microscopically (Figure 25–2). These inclusions are useful in the identification of these organisms in the clinical laboratory.

FIGURE 25–1 Life cycle of Chlamydia. The extracellular, inert elementary body enters an epithelial cell and changes into a reticulate body that divides many times by binary fission. The daughter reticulate bodies change into elementary bodies and are released from the epithelial cell. The cytoplasmic inclusion body, which is characteristic of chlamydial infections, consists of many daughter reticulate and elementary bodies. (Modified and reproduced with permission from Ryan K et al. Sherris Medical Microbiology. 3rd ed. Originally published by Appleton & Lange. Copyright 1994 by McGraw-Hill.)

FIGURE 25–2 Chlamydia trachomatis—light microscopy of cell culture. Long arrow points to cytoplasmic inclusion body of C. trachomatis; short arrow points to nucleus of cell. (Figure courtesy of Dr. E. Arum and Dr. N. Jacobs, Public Health Image Library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

All chlamydiae share a group-specific lipopolysaccharide antigen, which is detected by complement fixation tests. They also possess species-specific and immunotype-specific antigens (proteins), which are detected by immunofluorescence. C. psittaci and C. pneumoniae each have 1 immunotype, whereas C. trachomatis has at least 15 immunotypes.

Transmission & Epidemiology

C. trachomatis infects only humans and is usually transmitted by close personal contact (e.g., sexually or by passage through the birth canal). Individuals with asymptomatic genital tract infections are an important reservoir of infection for others. In trachoma, C. trachomatis is transmitted by finger-to-eye or fomite-to-eye contact. C. pneumoniae infects only humans and is transmitted from person to person by aerosol. C. psittaci infects birds (e.g., parrots, pigeons, and poultry, and many mammals). Humans are infected primarily by inhaling organisms in dry bird feces.

Sexually transmitted disease caused by C. trachomatis occurs worldwide, but trachoma is most frequently found in developing countries in dry, hot regions such as northern Africa. Trachoma is a leading cause of blindness in those countries.

Patients with a sexually transmitted disease are coinfected with both C. trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in approximately 10% to 30% of cases.

Pathogenesis & Clinical Findings

Chlamydiae infect primarily epithelial cells of the mucous membranes or the lungs. They rarely cause invasive, disseminated infections. C. psittaci infects the lungs primarily. The infection may be asymptomatic (detected only by a rising antibody titer) or may produce high fever and pneumonia. Human psittacosis is not generally communicable. C. pneumoniae causes upper and lower respiratory tract infections, especially bronchitis and pneumonia, in young adults.

C. trachomatis exists in more than 15 immunotypes (A–L). Types A, B, and C cause trachoma, a chronic conjunctivitis endemic in Africa and Asia. Trachoma may recur over many years and may lead to blindness but causes no systemic illness. Types D–K cause genital tract infections, which are occasionally transmitted to the eyes or the respiratory tract. In men, it is a common cause of nongonococcal urethritis (often abbreviated NGU), which is characterized by a urethral discharge (Figure 25–3). This infection may progress to epididymitis, prostatitis, or proctitis. In women, cervicitis develops and may progress to salpingitis and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Repeated episodes of salpingitis or PID can result in infertility or ectopic pregnancy.

FIGURE 25–3 Nongonococcal urethritis. Note watery, nonpurulent discharge caused by Chlamydia trachomatis. The urethral discharge caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae is more mucoid and purulent. (Courtesy of Seattle STD/HIV Prevention Training Center.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree