72

Central Nervous System Infections

CHAPTER CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Central nervous system (CNS) infections are often life-threatening and can have severe sequelae. These infections cause inflammation and edema within the unyielding cranium, resulting in damage to brain tissue and loss of function. The most common causes of CNS infections are bacteria and viruses, but fungi, protozoa, and helminths also cause these infections.

In addition to the history and physical examination, clinical diagnosis of CNS infections requires a spinal fluid analysis combined with neuroimaging using either magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scan. Microbiologic diagnosis of bacterial infections frequently is made using Gram stain and culture of spinal fluid and blood. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays and serologic tests are also useful. Antimicrobial therapy requires that the antibiotics be bactericidal and that they penetrate the blood–brain barrier. Some CNS infections, such as a brain abscess, often require surgical drainage.

CEREBROSPINAL FLUID ANALYSIS

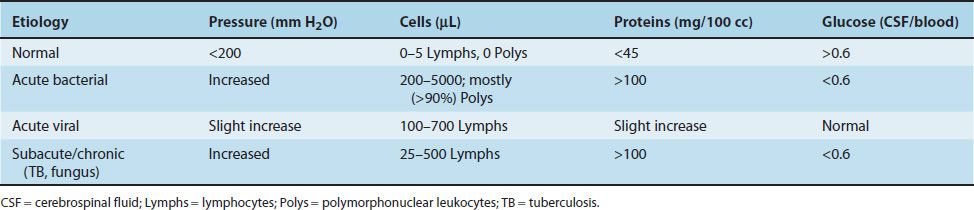

Examination of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is critical is making the diagnosis of CNS infections. CSF is obtained by performing a lumber puncture at the L3–L4 interspace. During the process, the CSF pressure is measured and fluid obtained for analysis of cells (both number and cell type, i.e., neutrophils or lymphocytes), protein, and glucose. The results of CSF analysis in acute bacterial meningitis, acute viral meningitis, and subacute meningitis are described in Table 72–1.

TABLE 72–1 Spinal Fluid Findings in Acute and Subacute Meningitis

Although CSF analysis is a very important step in the diagnosis of many CNS infections, a lumbar puncture should not be performed if there are signs of increased intracranial pressure, such as papilledema or focal neurologic signs, because herniation of the brainstem and death may occur. A CT scan should be performed prior to the lumbar puncture to determine whether a mass lesion, such as a brain abscess or cancer, is present. If a mass lesion is seen, a lumbar puncture should not be performed.

MENINGITIS

Definition

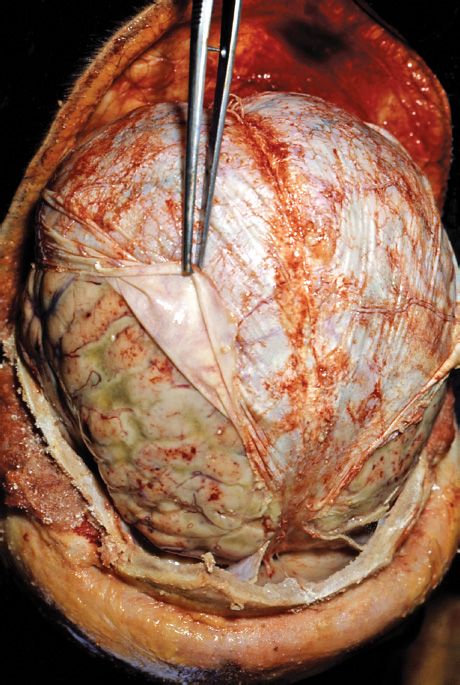

Meningitis is an infection of the meninges, the membranes that line the brain and spinal cord (Figure 72–1). Meningitis can be categorized as acute, subacute, or chronic depending on speed of the initial presentation and the rate of progression of the illness. Acute meningitis is caused by either pyogenic bacteria, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis, or viruses, such as Coxsackie virus and herpes simplex virus type 2. Viral meningitis is often called aseptic meningitis because routine cultures for bacterial pathogens are negative. Subacute meningitis is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and fungi, such as Cryptococcus. The causative organisms are often found in the spinal fluid located in the subarachnoid space.

FIGURE 72–1 Purulent meningitis. Note film of greenish pus in the subarachnoid space covering the brain. The dura is reflected back and held by forceps. (Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Pathophysiology

Hematogenous spread (i.e., bacteremia or viremia) is the most common route by which organisms reach the meninges. Direct spread via adjacent infections, such as otitis media and sinusitis; via neurosurgery, such as a shunt to relieve hydrocephalus; or via trauma, such as a fracture of the cribriform plate, occurs less frequently. The importance of hematogenous spread is emphasized by the success of the conjugate vaccines against S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, and Haemophilus influenzae type B that induce circulating IgG antibodies that neutralize the bacteria in the blood.

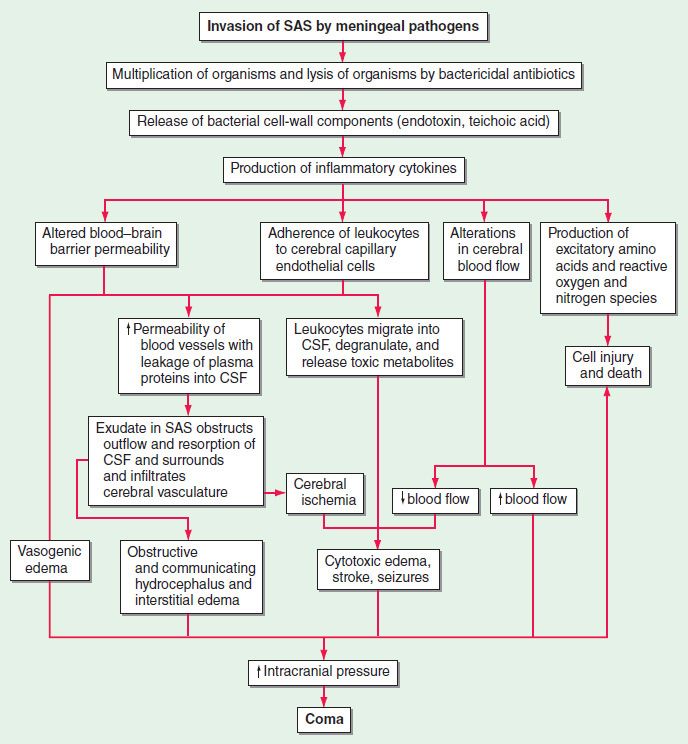

Acute bacterial meningitis begins with nasopharygeal colonization followed by local invasion, entry into the bloodstream, and invasion of the meninges (Figure 72–2). This is followed by an inflammatory response that causes many of the clinical manifestations, especially the edema resulting in increased intracranial pressure leading to headache. Cerebral vasculitis and infarction can also occur.

FIGURE 72–2 Pathogenesis of bacterial meningitis. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; SAS, subarachnoid space. (Reproduced with permission from Longo DL et al (eds). Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012. Copyright © 2012 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.)

Clinical Manifestations

Early symptoms include fever, headache, stiff neck (nuchal rigidity), and photophobia., If untreated, meningitis may progress to vomiting, seizures, focal neurologic deficits, and altered mental status. Different pathogens can present with different rates of clinical progression, from acute onset and rapid progression (hours to days) to subacute or chronic onset and slow progression (days to weeks). N. meningitidis infection can be associated with disseminated disease (meningococcemia) and result in petechial rash and ultimately purpura fulminans (Figure 72–3).

FIGURE 72–3 Purpura fulminans caused by Neisseria meningitidis. (Used with permission from Wolff K, Johnson R (eds): Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009. Copyright © 2009 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.)

Pathogens

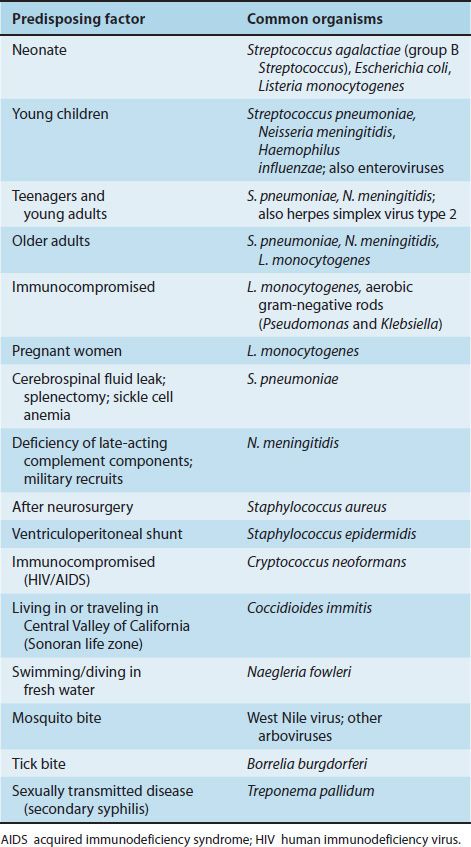

Acute Bacterial Pathogens

The most common bacterial cause of acute meningitis overall is S. pneumoniae. However, Streptococcus agalactiae (group B Streptococcus) predominates in neonates, and N. meningitidis is common in teenagers and young adults (Table 72–2). H. influenzae type B used to be an important cause in young children, but the widespread use of the conjugate polysaccharide vaccine has greatly decreased its incidence. Listeria monocytogenes is reasonably common in the very young and very old. Less common pathogens include Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease) and Treponema pallidum (syphilis).

TABLE 72–2 Organisms Causing Meningitis with Various Predisposing Factors

Acute Viral Pathogens

The most common viral causes of acute meningitis are enteroviruses such as Coxsackie virus and echovirus. Enteroviral meningitis occurs primarily in young children, and the peak incidence is in the summer and fall seasons. Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) is also a common cause of meningitis. Note that HSV-2 typically causes meningitis, whereas herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) causes encephalitis. Primary genital infections with HSV-2 are more likely to result in meningitis than recurrent HSV-2 infections. Primary and reactivation varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection can also be associated with meningitis. Although arboviruses typically cause encephalitis, arboviruses such as West Nile virus (WNV) and St. Louis encephalitis virus can also cause meningitis. Mumps virus used to be a common cause of meningitis, but widespread use of the mumps vaccine has greatly reduced its incidence.

Subacute and Chronic Meningitis

The most common causes of subacute and chronic meningitis are M. tuberculosis and fungi such as Cryptococcus, Coccidioides, and Histoplasma. Cryptococcal meningitis occurs most commonly in immunocompromised patients, such as those with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Diagnosis

A microbiologic diagnosis of acute bacterial meningitis is typically made by Gram stain and culture of CSF. Analysis of spinal fluid can distinguish between acute bacterial meningitis and viral meningitis (see Table 72–1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree