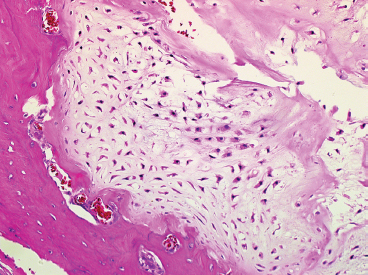

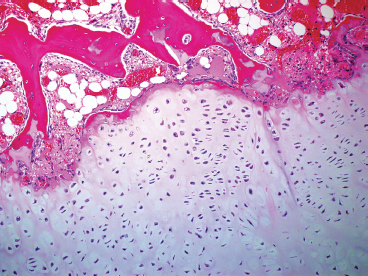

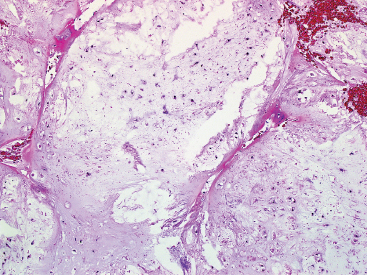

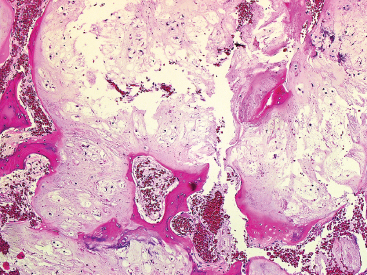

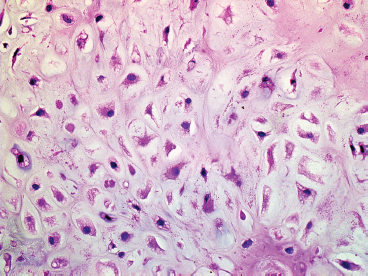

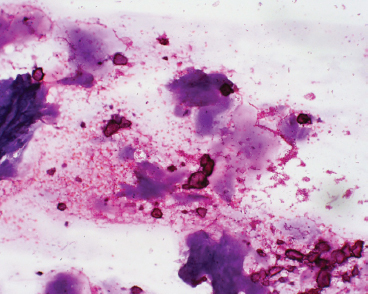

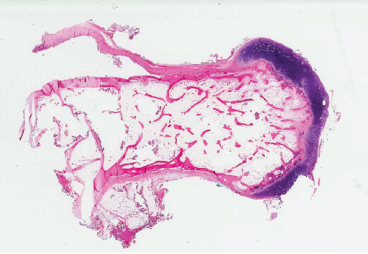

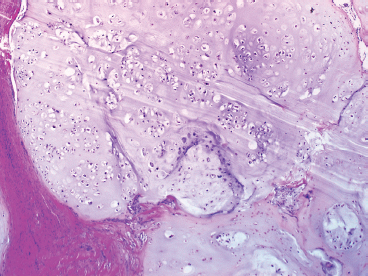

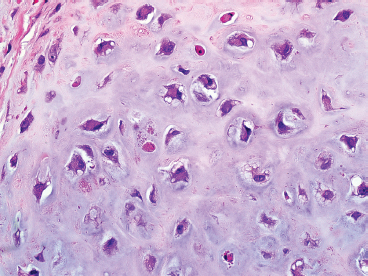

CARTILAGINOUS LESIONS 16.2 Osteochondroma and Bizarre Parosteal Osteochondromatous Proliferation (Nora’s Lesion) 16.7 Clear Cell Chondrosarcoma Enchondroma is a benign tumor of cartilage, sometimes also called chondroma. Enchondromas are relatively common, accounting for an estimated 10% to 25% of all bone tumors and are often incidental findings. One of the most common case scenarios is the discovery of a benign-appearing cartilaginous neoplasm on a radiographic workup for an unrelated complaint. About half of all enchondromas are sited in the small bones of the hands and feet. In this location, they are often subjected to pathologic fracture as a result of minor trauma. Other frequently affected sites include the humerus and femur. Enchondromas occur over a wide age range, but are more frequent in the second through fourth decades of life. There does not appear to be a strong sex predilection. Enchondromas are by definition, benign. There are rare case reports of malignant degeneration. Individuals with multiple enchondromas (Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome) are at an increased risk of developing malignant degeneration (secondary chondrosarcoma) of an enchondroma. On imaging, enchondromas appear as centrally placed lesions arising within the medullary cavity of the bone. A subset of tumors, known as periosteal enchondromas, arise on the surface of the bone. Enchondromas are frequently expansile, but the bone cortex should be intact, and there is often a sclerotic rim surrounding the lesion. When they arise in long bones, enchondromas frequently assume an elongate, oval configuration within the marrow space. One of the most distinctive radiographic characteristics of enchondromas is their tendency to show intralesional calcifications (Figure 16.1.1). These may be punctate or flocculent but frequently form a “ring-and-arc” type of pattern, which corresponds to peripheral calcification of nodules of cartilage. Cortical destruction and soft tissue permeation are radiographic features that are incompatible with a diagnosis of enchondroma. Enchondromas typically do not display molecular or cytogenetic abnormalities. This is in contrast to well-differentiated chondrosarcomas that often contain numeric and structural chromosomal abnormalities. In addition, chondrosarcomas frequently harbor mutations of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) or IDH2 genes. Absence of these mutations can be helpful in distinguishing between a benign enchondroma and a low-grade chondrosarcoma. Enchondromas are composed of multiple nodules of hyaline cartilage (Figure 16.1.2). The nodules are frequently separated by bone marrow elements, but are often confluent. Discrete nodules of cartilage often have a peripheral rim of thin lamellar bone that either partially or totally encases the cartilage (Figure 16.1.3). This finding corresponds to the rings-and-arcs pattern identified radiologically. Nodules that border the cortex should have sharp demarcation and should not penetrate the Haversian canal system. Hyaline cartilage nodules contain chondrocytes present within lacunar spaces that are variable in size. The chondrocytes may cluster in small aggregates or be randomly spaced. Individual chondrocytes should be round and small. Occasional lacuna may demonstrate binucleated cells. Mitotic activity is minimal. Distinction between enchondroma and low-grade chondrosarcoma on histology represents a challenge even to some of the most experienced pathologists. Enchondromas seldom “invade” the host bone, but are more often “confined” by the preexisting lamellar bone architecture. Enchondromas will not surround and entrap host bone (chondrosarcoma permeation pattern). This feature is often recognizable on en bloc resections, but can be difficult to detect on the more commonly submitted curettage specimens. Enchondromas of the hands and feet tend to be more cellular than those occurring in the long bones of the extremities. They can also show mild nuclear atypia, and as such, can be mistaken for a low-grade chondrosarcoma. The key to avoiding this diagnostic pitfall is to recognize the fact that increased cellularity and slight nuclear atypia in this site represents a normal variation. In addition, correlation with imaging features can be very reassuring that one is dealing with a benign process. Periosteal enchondromas also often show increased cellularity and cytologic atypia. Again, the radiologic features are helpful, as these are sharply demarcated lesions that do not invade the underlying cortex. Chondromas may also occur on the periosteal surface of the bone (Figure 16.1.4). Periosteal chondromas occur most commonly on the surface of the long bones and tend to be well marginated. They often erode the bone surface, but should not penetrate into the bone. They are often highly cellular and can lead to a misdiagnosis of a malignant cartilaginous neoplasm if one is not aware of this histologic variation (Figure 16.1.5). Small biopsy specimens of enchondroma, including both cutting needle core biopsy as well as aspiration cytology represent a true diagnostic challenge. In these types of specimens, the architectural pattern, alluded to earlier, will be completely unrecognizable. Instead, hyaline cartilage matrix material predominates (Figure 16.1.6). Individual chondrocytes should appear relatively small and innocuous in appearance. In aspirates, their relationship with the lacunar space is often preserved. Lack of conspicuous atypia and pleomorphism is a reassuring sign, but does not absolutely exclude a diagnosis of well-differentiated chondrosarcoma. In this instance, the best approach to diagnosis is careful correlation with the imaging features of the lesion. In the absence of atypical imaging features, a diagnosis of “low-grade chondroid neoplasm, consistent with enchondroma” is acceptable. One other potential diagnostic pitfall should be mentioned in this section. Aspirates and small core biopsies of a chondroblastic variant of osteosarcoma can sometimes appear as benign cartilage. This should be suspected if the sample is from a very young patient, the imaging features suggest an aggressive neoplasm, and there is clinical concern for a malignant process. FIGURE 16.1.1 Imaging of an enchondroma. This lesion shows an intact cortex. Within the lesion is a pattern of “rings and arcs,” which corresponds to lobules of cartilage with peripheral calcification. FIGURE 16.1.2 Enchondromas are lobular in configuration. In this example, the lobules are almost confluent. Note also the low overall cellularity. FIGURE 16.1.3 This lobule of enchondroma is separated from the bone marrow by a thin rim of calcified bone. This is an important feature that helps exclude a low-grade chondrosarcoma. FIGURE 16.1.4 A periosteal chondroma emanating from the periosteal surface of the bone. FIGURE 16.1.5 Periosteal chondromas frequently show moderate cytologic atypia of the chondrocytes. FIGURE 16.1.6 Cytologic preparations from enchondroma are composed largely of abundant cartilaginous matrix material. In this example, small fragments of bone are present as well. 16.2 Osteochondroma and Bizarre Parosteal Osteochondromatous Proliferation (Nora’s Lesion) Osteochondromas are benign small projections of both bone and articular-type cartilage that arise on the external surfaces of bone. It is important to note that this lesion is always in contiguity with the underlying bone and marrow cavity, a feature that helps distinguish osteochondroma from some of its mimics. Osteochondromas are most often solitary, but can occur as multiple lesions as well. The solitary form of osteochondroma is relatively common and is thought to represent up to 35% of all bone tumors. These lesions are often asymptomatic and are frequently incidental findings on imaging studies performed for an unrelated reason. Occasionally a solitary osteochondroma will cause symptoms, usually pain in relation to impingement on adjacent structures. Most cases of osteochondroma present in young individuals within the first three decades of life. Frequent sites of osteochondroma include the metaphyseal regions of the long bones, particularly the distal femur, proximal tibia or fibula, and the humerus. Occasionally they arise in the flat bones, with either the pelvis or scapula being common sites. An estimated 15% of patients with osteochondroma have multiple lesions. This is known as hereditary osteochondromatosis or hereditary multiple exostosis. This is almost always linked to a germline mutation in one of the tumor suppressor genes EXT1 or EXT2. This pattern of involvement is an autosomal dominant inherited disorder. Individuals with multiple osteochondromas or exostoses are at an elevated risk of malignant transformation (into chondrosarcoma) with a low but significant risk (between 5% and 25%). Solitary osteochondromas are also at risk, but this complication is seen very rarely (estimated at up to 3%). On imaging, osteochondromas are usually very distinctive. In the long bones, they appear as sessile or pedunculated lesions projecting from the surface of the bone (Figure 16.2.1). Cross-sectional imaging usually shows continuity with the adjacent host bone marrow space. In addition, cross-sectional imaging is useful for determining the size of the cartilaginous cap. Cap width exceeding 2 cm is associated with a higher incidence of malignant transformation. As such, a thick or irregular-appearing cartilaginous cap, a soft tissue mass, or irregular calcification of the cartilage should raise suspicion for an associated chondrosarcoma. Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation, commonly referred to as Nora’s lesion or BPOP, is a histologically similar type of bone and cartilaginous growth that tends to occur in the hands of adult patients (Figure 16.2.2). This lesion occasionally causes diagnostic difficulty because the relationship to the host bone is less clear and there may be some histologic atypia. Well-formed osteochondromas are usually composed of both cortical and trabecular bone, with a small, often discontinuous cap at the periphery of the lesion (Figure 16.2.3). The cortical bone and marrow space should be in continuity with the host bone, although this feature is difficult to determine on histologic sections (and should prompt review of imaging studies). Marrow space is identifiable between the cortical bone of the stalk, and it is often filled with fat and hematopoietic elements. Examination of the cartilaginous cap is the most critical part of histopathologic assessment of osteochondroma. As mentioned previously, the cap should not exceed 2 cm in overall width. In general, older individuals (and older osteochondromatous lesions) have smaller cartilaginous caps than younger lesions. The cap should have an orderly architecture. The region of cartilage closest to the medullary bone often shows alignment similar to that seen in the enchondral ossification pattern of bone growth (Figure 16.2.4). Secondary chondrosarcoma is associated with a less orderly pattern of growth. In this instance, one often identifies irregular round nodules of cartilage, focal areas of hypercellularity, and isolated nodules away from the main lesion, often extending into the adjacent soft tissues (Figure 16.2.5). Mitotic activity, myxoid stromal change, and chondrocyte atypia (except in the hands; see Nora’s lesion in the following) are other signs of malignant transformation. BPOP or Nora’s lesion tends to have a less orderly appearance than an osteochondroma. It tends to be more hypercelluar with less organization of the cartilaginous component. There may be modest nuclear atypia and atypical chondrocytes with numerous binucleate forms (Figure 16.2.6). The bone and marrow spaces are often less well formed and may show striking hypercellularity and mitotic activity. Despite some alarming features, these should be considered benign entities. They may recur after excision, but this should not prompt a diagnosis of malignancy. There are rare reports of fine needle aspiration findings of both osteochondroma and Nora’s lesion. The latter, in particular, can often lead to a misdiagnosis of malignancy based on isolated cytologic atypia. Because of the importance of architecture in confirming the diagnosis of these lesions, fine needle aspiration is probably not the best diagnostic technique for a suspected BPOP or osteochondroma. Likewise, assessment of the cartilaginous cap (for either benign features or evidence of malignant transformation) by fine needle aspiration is not recommended. FIGURE 16.2.1 A pedunculated osteochondroma on the posterior aspect of the proximal tibia. Osteochondromas tend to point away from the joint. FIGURE 16.2.2 Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferations (Nora’s lesion) have a somewhat similar radiographic appearance, but occur in the hands and feet. FIGURE 16.2.3 This example of an older osteochondroma shows trabecular bone with a thin cap of cartilage on one surface. FIGURE 16.2.4 Examination of the cap of osteochondromas shows a somewhat orderly arrangement of chondrocytes in a linear pattern similar to that seen in the process of normal enchondral ossification. FIGURE 16.2.5 Malignant transformation of a cartilaginous cap is heralded by an increase in size of the cap, extension of the cartilaginous element into the adjacent soft tissues, loss of chondrocyte organization, and focal hypercellularity. FIGURE 16.2.6 The chondromatous areas of Nora’s lesion can show moderate to marked cytologic atypia. Chondroblastoma is a benign tumor, commonly arising in the epiphysis or apophysis of long bones. Occasional cases have been documented in the flat bones of the pelvis and shoulder (scapula). This is an uncommon lesion, representing about 15% of all primary bone tumors. Chondroblastoma is a lesion that is most frequently diagnosed in younger individuals still undergoing active bone growth (open epiphyses). As such, this diagnosis should be distinctly uncommon in patients over age 25. In an older adult patient population, alternative diagnoses such as giant cell tumor or clear cell chondrosarcoma should be considered. Patients usually complain of gradually increasing pain and tenderness in the affected region. On imaging, chondroblastomas are frequently lucent or lytic lesions with sclerotic borders. The volume of the neoplasm should occupy one-half or less of the articular end of the bone, and the cortical borders should be intact (Figure 16.3.1). Occasionally, punctate calcifications can be identified in the lesion, but this is not a consistent finding. Chondroblastomas are benign lesions of bone and curettage with packing or grafting is often the treatment of choice. Recurrences are rare except in sites where it may be difficult to achieve a complete resection.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

HISTOPATHOLOGY

CYTOLOGIC FEATURES

HISTOPATHOGIC FEATURES

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree