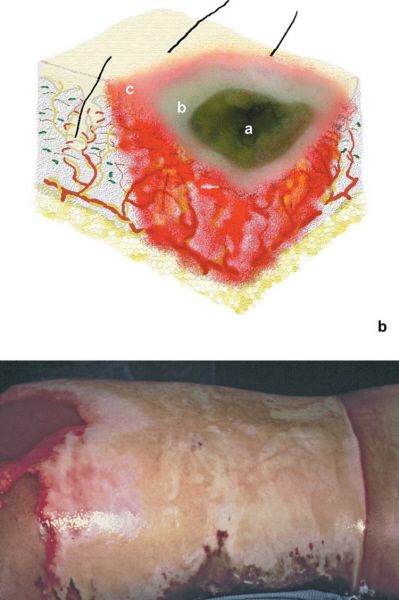

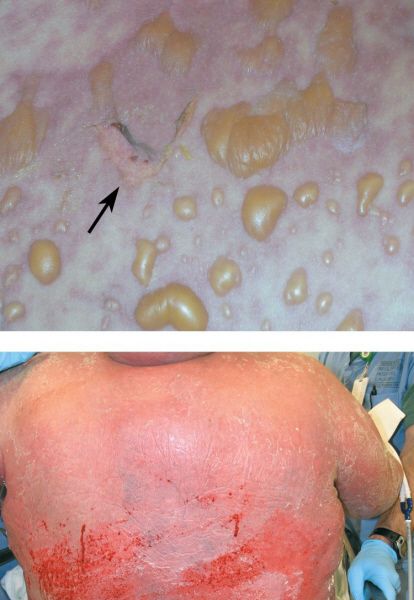

Burns of varying severity—zone of injury correlates with burn depth. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

•First-degree burns are limited to the epidermis

•A long day in the sun

•Have blanching erythema and pain

•Second-degree burns involve the epidermis and variable amounts of dermis

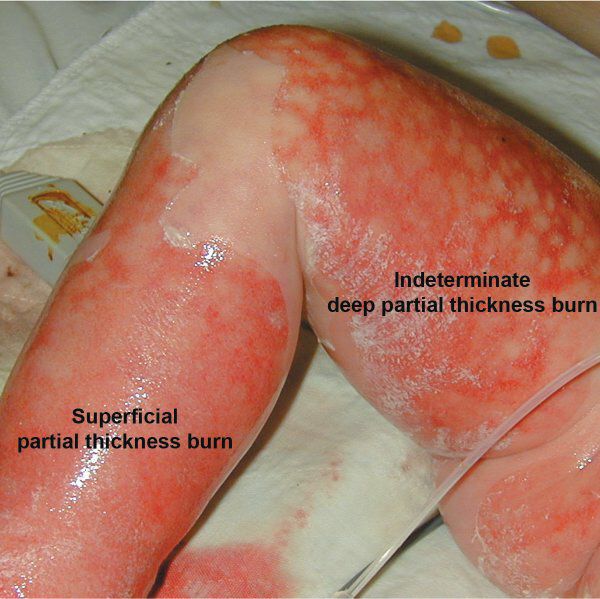

•Superficial second-degree burns

•Involve the epidermis and superficial dermis

•Blisters are present

•Burns are pink, moist, and tender

•Healing takes place within 2 to 3 weeks, often with minimal scarring

•Deep second-degree burns

•Extend into deeper dermis

•Skin is usually cherry red, mottled, or white

•Long healing time and increased risk of infection

•Greater potential for hypertrophic scar formation

•Skin grafting is usually required

•Third-degree burns

•Full-thickness damage to epidermis and dermis with extension into subcutaneous tissue

•White or leather appearance

•Often painless due to nerve injury

•Debridement is necessary to remove necrotic tissue, which is prone to infection

•Subsequent skin grafting is always required (unless wound is very small)

•Fourth-degree burns

•Deep muscle, bone, or tendon are destroyed

•Managed similar to third-degree burns

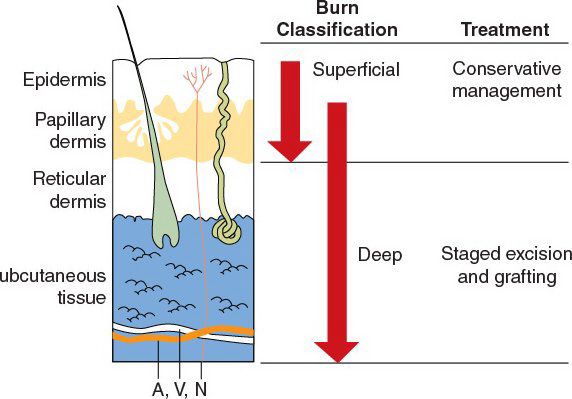

Burn classification and treatment.

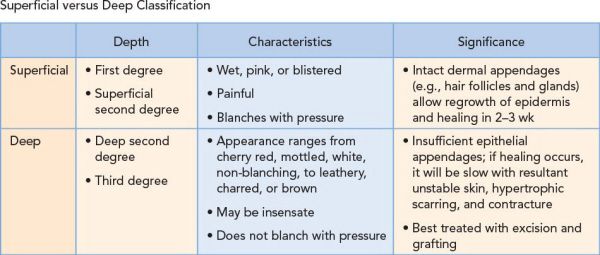

Superficial versus Deep Classification

Superficial burns may be treated conservatively, as opposed to deep burns, which require operative debridement.

A 68-year-old man injured in a house fire sustains facial burns. The examination reveals deep facial burns with evidence of carbonaceous sputum. What is the next step in management?

This patient should be intubated, stabilized, and transferred to a designated burn center. Carbonaceous sputum is a sign of inhalation injury and should be taken seriously because of the possibility of an impending airway emergency.

•Caused by inhaling products of combustion (cyanide gas, carbon monoxide, burnt silk, paper, etc.)

•Three components of injury

•Tissue hypoxia decreased oxygen carrying capacity of blood

decreased oxygen carrying capacity of blood

•Thermal injury upper airway edema in 18 to 24 hours

upper airway edema in 18 to 24 hours

•Lung injury obstructive atelectasis and bronchoconstriction

obstructive atelectasis and bronchoconstriction

•Signs and symptoms—when to suspect inhalational injury

•Loss of consciousness

•Noxious chemicals involved

•Carbonaceous sputum

•Facial burns/singed nasal hairs/eyebrows

•Hoarse voice

•Erythema/swelling of oropharynx

•Diagnosis is made from any of the above findings with one of the following:

•Carboxyhemoglobin >10%

•Oxygen saturation <90%

•Positive findings on laryngoscopy

•Positive findings on bronchoscopy

•High-probability V/Q scan

•Treatment: High-flow oxygen mask (intubate early as appropriate)

•Oxygen will compete with carbon monoxide for hemoglobin binding

•Carbon monoxide has a have life of hours (320 minutes on room air, 90 minutes on 100% oxygen, and 23 minutes on hyperbaric therapy)

Patients with facial and/or neck burns or other signs of inhalational injury should be intubated.

A 43-year-old woman presents with cutaneous eruptions on her face, chest, bilateral upper extremities, and abdomen (approximately 40% of total body surface area [TBSA]). These eruptions initially developed 3 days ago. In that time, the patient’s wounds have rapidly evolved from a papular exanthem to confluent blisters with epidermal detachment. Also, there are multiple lesions noted in her oropharynx. The patient’s history is significant for the recent restarting of Dilantin for epilepsy. What is her diagnosis?

This is a classic presentation of toxic epidermal necrolysis syndrome (TENS), which can mimic thermal injuries.

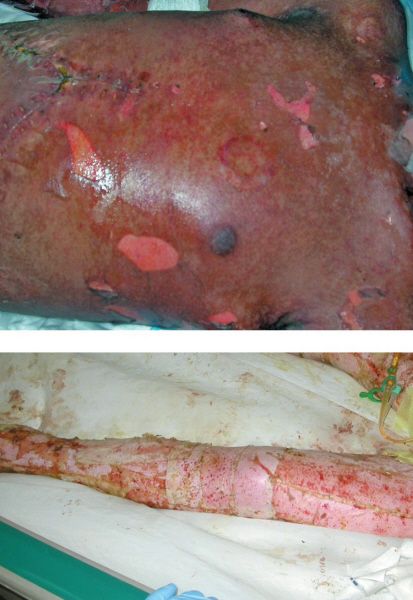

Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Syndrome

•Rapidly evolving mucocutaneous reaction

•Characterized by widespread erythema, necrosis, and bullous detachment of the epidermis resembling scalding

Toxic epidermal necrolysis. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

•Mainly attributed to build up of drug metabolites

•Associated with:

•Sulfonamide antibiotics

•Anticonvulsants (phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproic acid)

•Also reported with NSAIDs, allopurinol, vancomycin, corticosteroids, antiretrovirals

•Some infections

•Classification is largely based on extent of epidermal detachment and morphology of skin lesion

•Stevens-Johnson syndrome: Epidermal detachment less than 30% of body surface area involved with widespread erythematous or purpuric macules or flat atypical targets

•TENS: Epidermal detachment greater than 30% of the body surface area in large epidermal sheets and without purpuric macules

•Mucosal lesions (oral, vaginal, conjunctival) are also evident

•Diagnosis

•Nikolsky sign: Skin separation with horizontal traction

•Due to dermal–epidermal separation

•Definitive diagnosis is made on biopsy

•Have keratinocyte necrosis at the dermal–epidermal junction

•Treatment is supportive—stop any possible offending drug

•Do NOT give steroids

•Prevent wound desiccation with topical antimicrobials and xenografts

TENS is a dermatologic abnormality that mimics burn injury and is mainly attributed to sulfonamides or phenytoin.

A 17-year-old student sustains a 50% TBSA gasoline burn. Upon examination, you find that the patient’s bilateral upper extremity burn is circumferential. The area is white and tense. After acute resuscitation, what is the next step in therapy?

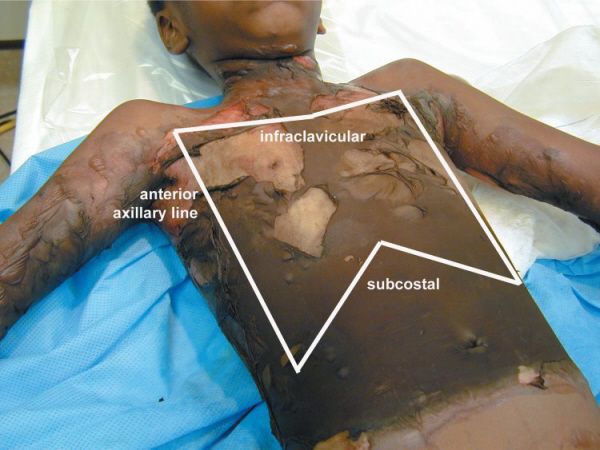

Urgent and proper placement of an escharotomy is required to prevent vascular or respiratory compromise in patients with restrictive burns.

Escharotomy incisions. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

•A longitudinal incision aimed at releasing tissue pressure to restore perfusion

•Common indications

•Circumferential deep partial thickness or full thickness burns

•Difficulty in ventilating patients with significant chest/torso burns

•Full-thickness incision

•Must go through the entire depth of the burn to allow tissue expansion and a return of blood flow

•Particularly relevant to the neck, thorax, and extremities

•Extremity escharotomy: Place incisions on mid-medial and mid-lateral aspect of extremity and extend all the way distally

•Chest wall escharotomy: Place incisions at anterior axillary lines bilaterally which is connected by a subcostal incision (makes an “H” across chest)

When performing an escharotomy, general or topical anesthesia is not required.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree