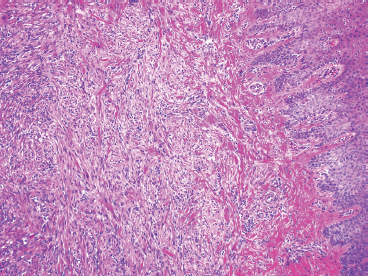

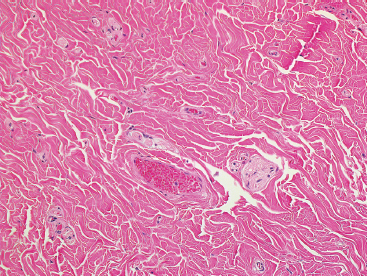

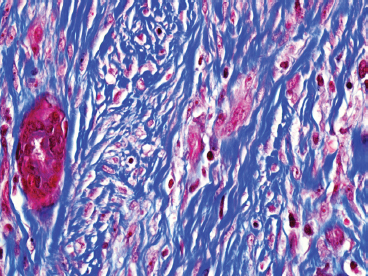

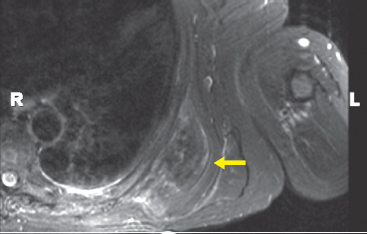

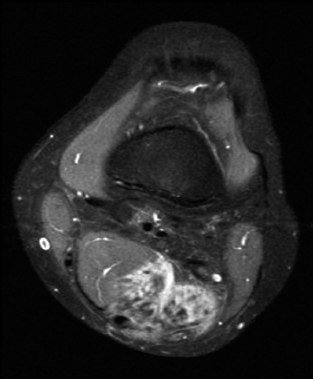

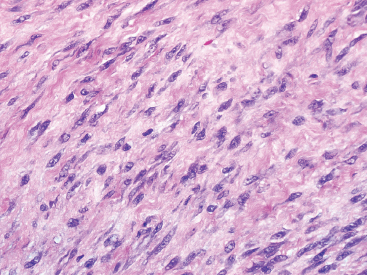

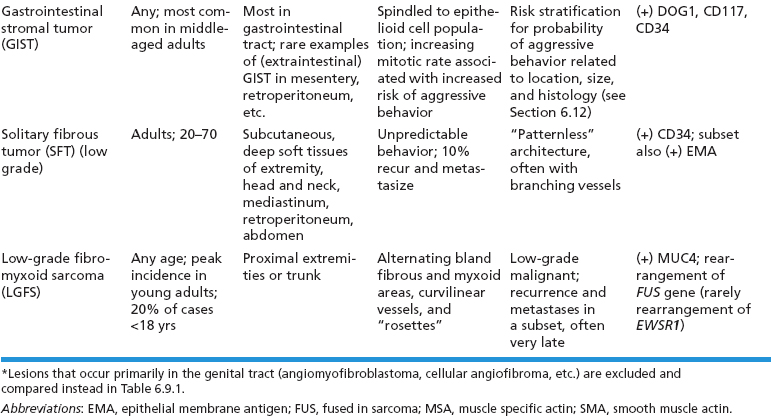

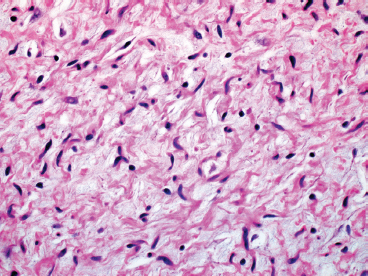

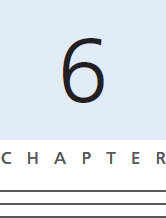

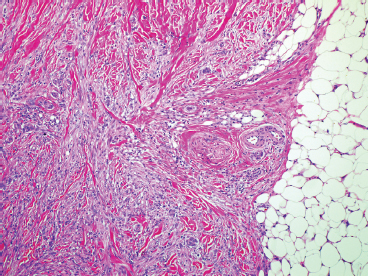

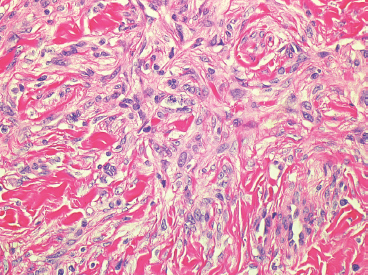

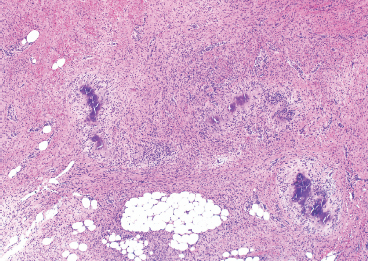

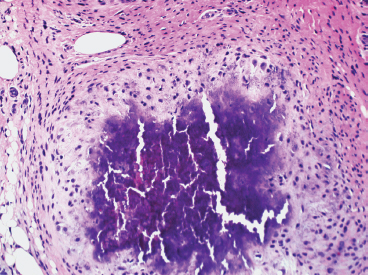

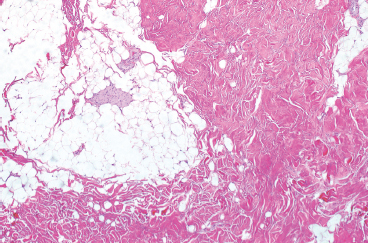

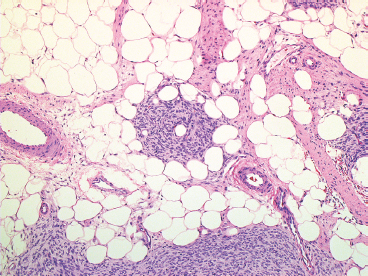

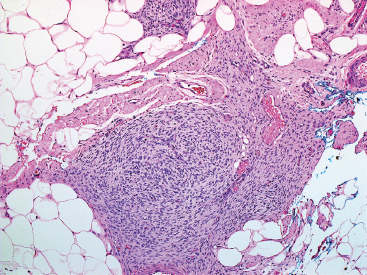

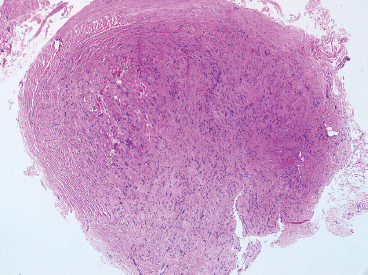

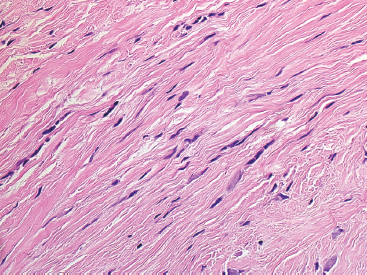

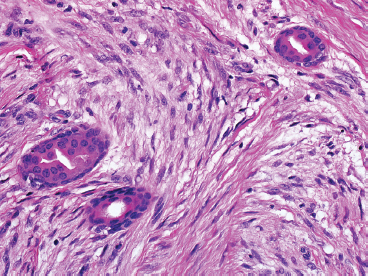

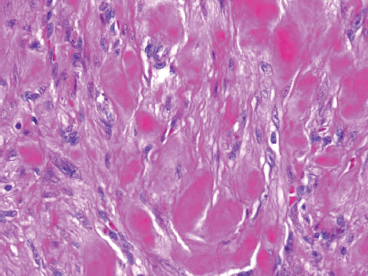

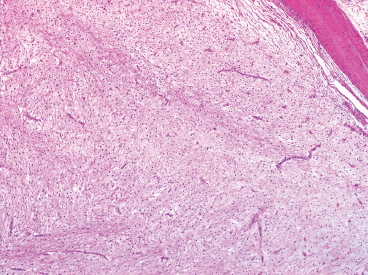

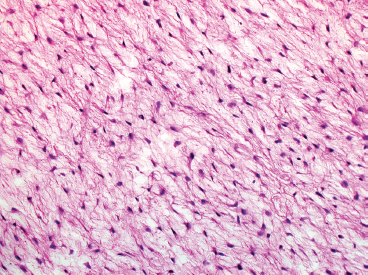

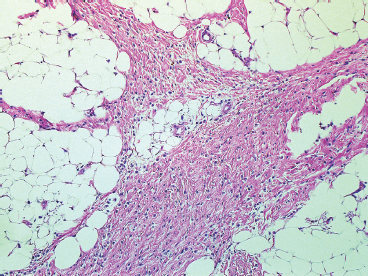

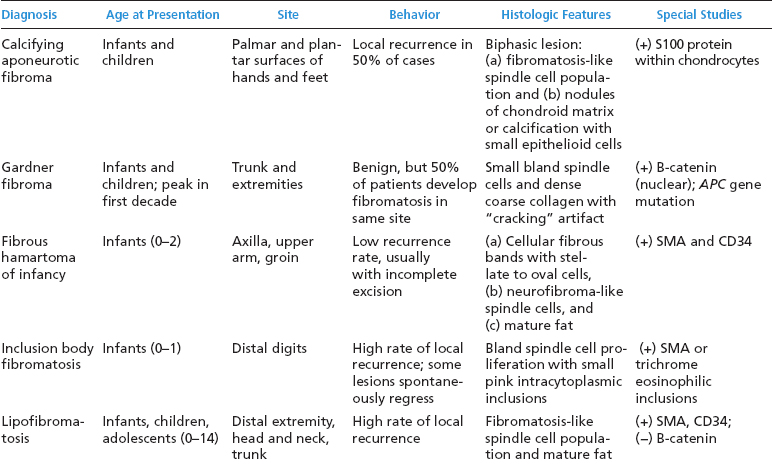

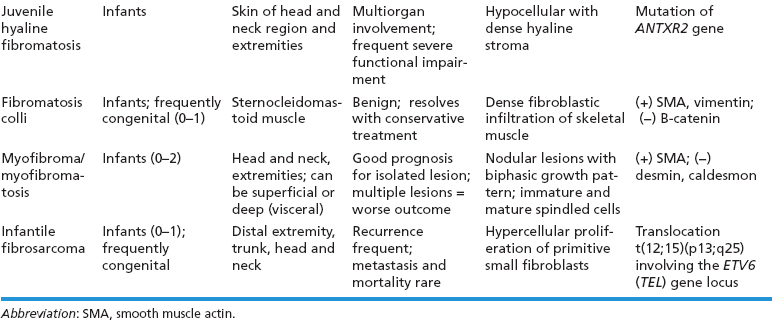

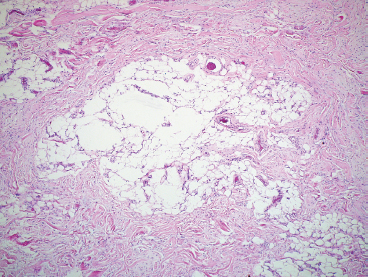

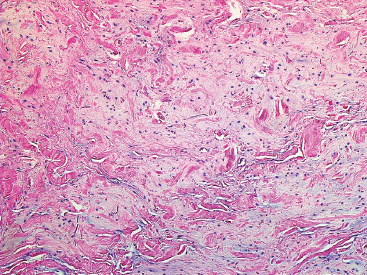

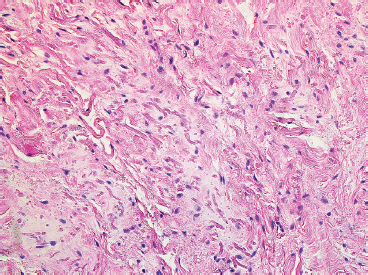

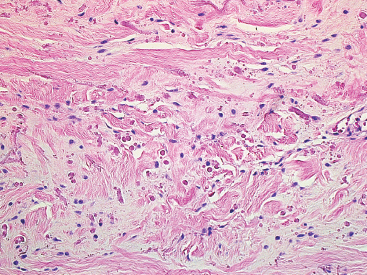

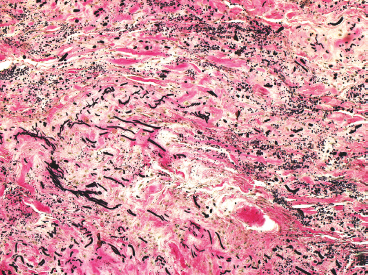

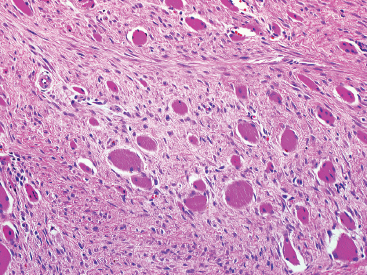

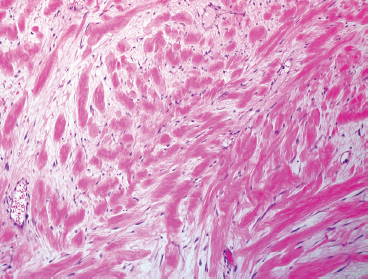

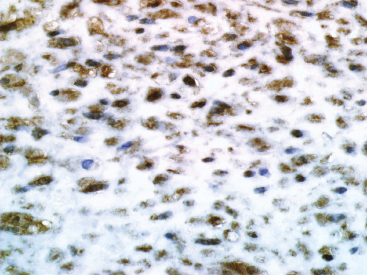

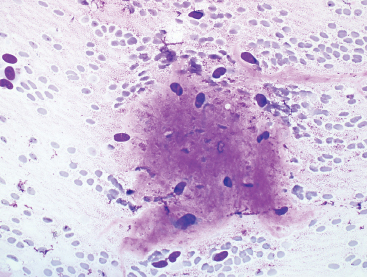

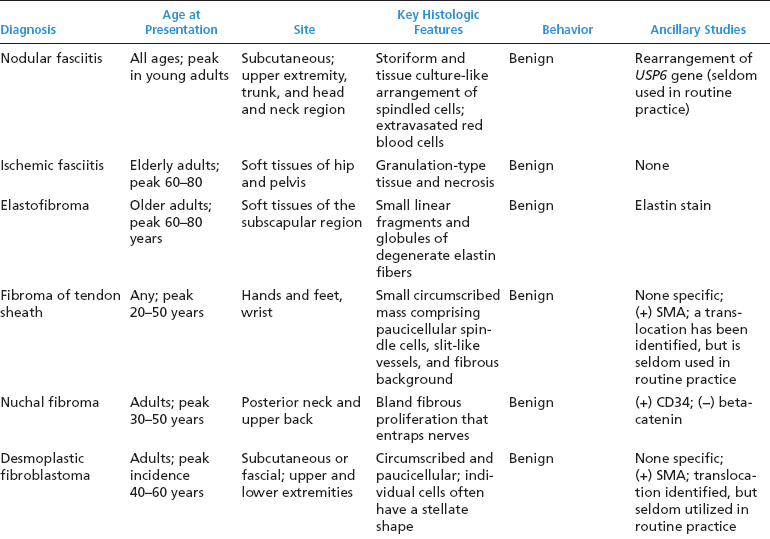

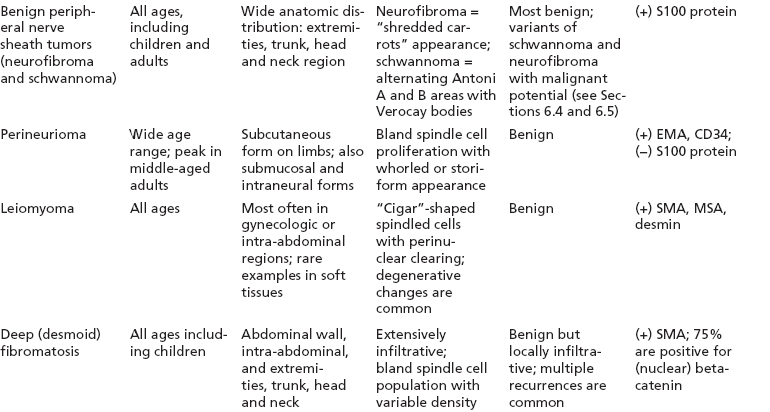

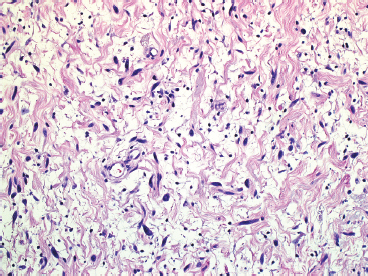

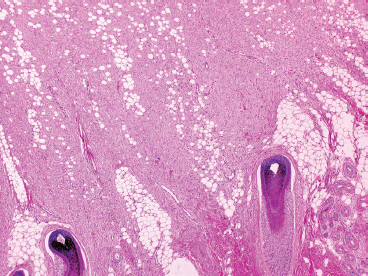

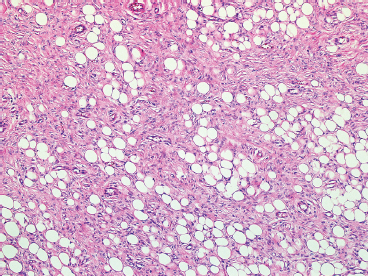

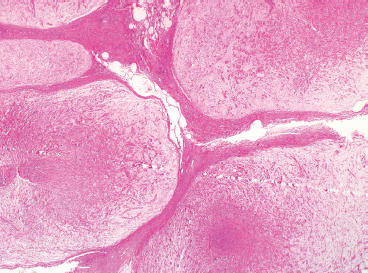

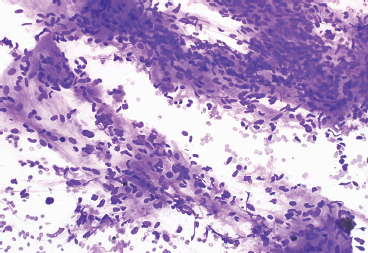

BENIGN AND LOW-GRADE SPINDLE CELL TUMORS 6.8 Additional Variants of Fasciitis 6.12 Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor 6.14 Myofibroma and Myofibromatosis 6.16 Low-Grade Fibromyxoid Sarcoma Fibromas represent a very diverse set of lesions that have a common histologic feature: the presence of bland fibrosis. They can be of pure fibroblastic, fibrohistiocytic, or myofibroblastic origin. In this section, some of the distinctive clinical subtypes of low-grade and benign fibrous lesions are described and illustrated together. Dermatofibromas are common benign lesions of fibrohistiocytic origin that tend to occur in the dermis and subcutaneous soft tissues. They occur most commonly in adults and present as raised, slow-growing nodules. Histologically, they are comprised of a poorly delineated dermal proliferation of spindled cells (Figure 6.1.1). They often extend focally into the adjacent soft tissues, but should not invade extensively or in an infiltrating manner (more characteristic of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans) (Figure 6.1.2). The spindled cells are arranged in short fascicles, usually with a vague storiform configuration (Figure 6.1.3). Variations on histology include the presence of Touton-type giant cells, extensive xanthomatous change, and stromal hyalinization. Dermatofibroma expresses Factor XIIIa immunohistochemically, but usually does not show diffuse positivity for CD34. Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma is a rare tumor with a predilection for children and adolescents. It occurs most commonly on the palmar surfaces of the hands as well as the plantar surfaces of the feet. Occasionally, it occurs on the wrist, fingers, or more proximal soft tissues of the extremity. It usually presents as a slow-growing, ill-defined mass associated with either a tendon or aponeurosis. Because this lesion is infiltrative, it may be difficult to remove completely, and there is a relatively high risk of local recurrence. Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma is one of a number of pediatric spindle cell tumors. The clinical, histologic, and diagnostic features of the spindle cell tumors of children are summarized in Table 6.1.1. Histologically, calcifying aponeurotic fibroma is characterized by a proliferation of fibrous tissue that tends to simulate fibromatosis (Figure 6.1.4). Depending on the age of the lesion, different secondary characteristics may be identified. Relatively immature lesions often have foci of chondroid metaplasia associated with giant cells and foci of small granular-type calcifications. As the lesion becomes more mature, the chondroid matrix becomes replaced with areas of amorphous type of calcification as well as hyalinization of the fibrous component (Figure 6.1.5). Nuchal fibroma is a rare, benign lesion with a strong predilection for the dermis and superficial subcutaneous tissues of the posterior neck or upper back. Patients tend to be middle-aged or older adults, and there is a strong association with diabetes mellitus. Nuchal-type fibromas are painless and can often reach a large size and tend to be infiltrative. They can occasionally recur after excision, but have not been reported to metastasize. The main differential diagnosis of nuchal fibroma is with Gardner fibroma (see the following). The distinction is important, as patients with Gardner fibroma often have a germline genetic defect, which predisposes them to other forms of malignancy. Histologically, nuchal-type fibromas are characterized by a dense, hypocellular collagneous proliferation throughout the superficial soft tissues. Fibroblasts are sparse and very bland in appearance. There may be entrapment of small nerve fibers or subcutaneous fat within a nuchal-type fibroma (Figure 6.1.6). This type of fibroma typically expresses CD34 and is negative for markers of smooth muscle differentiation such as smooth muscle actin (SMA) or desmin. Gardner fibromas are plaque-like dense masses, which tend to occur in the paraspinal soft tissues, trunk, abdomen, or extremities. The majority of individuals with Gardner-type fibroma have a history of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) caused by a defect in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene. Age at presentation for Garner fibroma (and other manifestations of FAP) are variable, but can begin as early as childhood and adolescence. The histology of Gardner fibroma is nonspecific. It consists of a bland proliferation of spindle cells set in a dense collagenized stroma (Figure 6.1.7). Gardner fibroma tends to show immunohistochemical expression of CD34 and in some instances, nuclear localization of beta-catenin. Fibrous hamartoma of infancy is a lesion that occurs in the first 2 years of life. It has a distinctive predilection for the axillary region, but occasionally can occur in other sites including upper arm and shoulder, thigh, groin, back, and forearm. Fibrous hamartoma is a benign lesion that is cured by excision. On histologic sections, fibrous hamartoma of infancy displays three distinct components: fibrous trabeculae in an intersecting pattern, islands of loosely arranged spindle cells, and mature fat (Figure 6.1.8). The fibrous component is often dense or collagenized, but comprises bland fibroblastic cells with elongated nuclei. The loose component is often arranged in small islands dispersed throughout the lesion (Figure 6.1.9). On high power, these appear more myxoid in character and tend to contain small primitive spindle cells with scant cytoplasm. The fat component may be interspersed throughout or, in more mature lesions, confined to the periphery. Fibroma of tendon sheath is a relatively uncommon lesion that occurs most often in association with the tendons of the fingers. It presents as a small, very firm, and usually painless nodule. It is usually very well circumscribed, and an attachment to a tendon is often noted at the time of excision (Figure 6.1.10). Histologically, fibroma of the tendon sheath is bland and paucicellular (Figure 6.1.11). There may be rare elongated vessels present throughout. Variations on the classic histologic appearance include focal myxoid or cystic degenerative change as well as osseous or cartilaginous metaplasia. Fibroma of tendon sheath is benign, but may recur if not completely excised. It displays evidence of myofibroblastic differentiation in that it displays positive immunohistochemical staining for SMA. Cytogenetic study of a single case has demonstrated a translocation t(2;11)(q31;q12) that is also present in desmoplastic fibroblastoma, raising the possibility that these may be closely related entities. The differential diagnosis of fibroma of tendon sheath would also include the so-called “giant cell-poor” variant of giant cell tumor of tendon sheath. Inclusion body fibromatosis represents a benign proliferation of fibroblasts that tends to occur on the digits of young children. This entity is also referred to as digital fibrous tumor of childhood and infantile digital fibroma. It is an extremely rare entity, but should be considered in an infant who develops one or more fibrous lesions of the distal digits of the hands or feet. Nodules of inclusion body fibromatosis tend to reach about 2 cm in size. They are centered in the soft tissues, but cause a dome-shaped mass, which produces tightness and redness of the overlying skin. Inclusion body fibromatosis is benign, but has a tendency to recur. Histologically, this lesion is composed of a moderately cellular proliferation of spindled cells arranged in interlacing fascicles. Unlike other forms of fibroma or fibromatosis, the lesional cells tend to be plump and ovoid in shape. The spindle cell proliferation infiltrates and entraps adjacent adnexal structures (Figure 6.1.12). The defining feature of inclusion body fibromatosis is the presence of small intracytoplasmic red inclusions. These may be difficult to see on routine hematoxylin and eosin, but are often highlighted by Masson’s trichrome stain or can be highlighted by immunohistochemical staining for SMA (Figure 6.1.13). Hyaline fibromatosis is an autosomal recessive disorder that tends to affect children very early in life. Nodules of densely hyalinized material begin to form in infancy (infantile form) in skin, soft tissue, and visceral organs. The juvenile form of the disease tends to present slightly later and be less severe with a more protracted clinical course. Both forms of this disease are associated with a mutation of the capillary morphogenesis protein 2 gene on chromosome 4. Histologically, these lesions are characterized by an abundance of thick, hyalinized material with rare intervening bland, small spindle cells (Figure 6.1.14). There is extensive histologic overlap with a number of other lesions in this age group. As such, diagnosis is dependent on the prominence of the hyaline material as well as demonstration of the genetic mutation associated with hyaline fibromatosis. Desmoplastic fibroblastoma, also commonly referred to as collagenous fibroma, is an extremely rare, benign entity of the superficial soft tissues. It occurs most commonly in adults, with a median patient age of around 50 years. Men are more frequently affected than women, with a 4 to 1 increased incidence in males. The most commonly affected sites include upper and lower extremities, hands and feet, upper back, and the abdominal wall (Figure 6.1.15). These are slow-growing lesions and because of their superficial location, tend to present while still relatively small (3 cm average size). Desmoplastic fibromas tend to be well-circumscribed but unencapsulated lesions (Figure 6.1.16). They are composed of dense, hypocellular fibrous tissue, occasionally with peripheral entrapment of fat or muscle. Individual cell nuclei are sparse and often very widely spaced. They tend to be spindled or occasionally stellate in shape (Figure 6.1.17). They also have fine, open chromatin and a prominent nucleolus. Lipofibromatosis is a benign pediatric tumor comprising a mixture of mature-appearing fat and a fibromatosis-like spindle cell proliferation. This lesion tends to occur in the hands and feet of children, with an age range of infancy to adolescence. Lipofibromatosis is commonly ill defined and infiltrative. There is a high incidence of local recurrence. Histologically, this lesion is composed of cellular fascicles of spindled cells admixed with mature-appearing fat (Figure 6.1.18). The fibroblastic component has a tendency to spread along septal planes. Nuclear atypia and mitotic activity should not be prominent. FIGURE 6.1.1 A dermatofibroma in the superficial dermis. These are poorly delineated lesions of fibrohistiocytic origin. The overlying epidermis is often hyperplastic. FIGURE 6.1.2 Deep extent of a dermatofibroma. There is often focal finger-like extension into the subcutaneous soft tissues. Extensive or diffuse infiltration should not be present. FIGURE 6.1.3 Dermatofibroma with a characteristic storiform proliferation of spindled cells surrounded by a collagen network. FIGURE 6.1.4 A low-power view of calcifying aponeurotic fibroma showing its fibromatosis-like infiltrating appearance. FIGURE 6.1.5 A focus of calcification of calcifying aponeurotic fibroma with a peripheral halo of more rounded epithelioid cells. The dense calcification indicates this is probably a more mature lesion. FIGURE 6.1.6 Nuchal fibroma is a poorly delineated proliferation of dense fibrous tissue. It frequently entraps normal fat and peripheral nerves. FIGURE 6.1.7 Dense fibrous tissue of Gardner fibroma. There is often a cracking artifact between the very dense and coarse bundles of fibrous tissue. FIGURE 6.1.8 Fibrous hamartoma of infancy composed of three elements: mature fat, fibrous tissue, and immature mesenchymal tissue. FIGURE 6.1.9 The immature element of fibrous hamartoma of infancy tends to be composed of slightly larger cells that often display a whorled or organoid appearance. FIGURE 6.1.10 A well-circumscribed fibroma of tendon sheath. FIGURE 6.1.11 Fibroma of tendon sheath is usually sclerotic and relatively paucicellular. FIGURE 6.1.12 Inclusion body fibromatosis showing entrapment of skin adnexal structures. FIGURE 6.1.13 Masson’s stain is helpful in highlighting the small intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies that are characteristic of this inclusion body fibromatosis. FIGURE 6.1.14 Juvenile hyaline fibrosis is characterized by an extensive sclerotic hyalinized matrix, which entraps small plump fibroblasts. FIGURE 6.1.15 Imaging of a desmoplastic fibroblastoma located in the superficial soft tissues of the foot. FIGURE 6.1.16 Desmoplastic fibroblastoma typically appears well demarcated, but microscopic extension into adjacent soft tissues is identified in a significant percentage of cases. FIGURE 6.1.17 Desmoplastic fibroblastoma with a hypocellular myxocollagenous background. FIGURE 6.1.18 Lipofibromatosis composed of fascicles of spindle cells associated with mature fat. TABLE 6.1.1 Differential Diagnosis of Pediatric Spindle Cell Lesions Elastofibroma is a benign lesion that arises almost exclusively in the soft tissues of the scapular region of elderly individuals (Figure 6.2.1). It is poorly delineated and presents as a slow-growing painless soft tissue mass. It is not unusual for the lesion to be present bilaterally. Elastofibroma may be partially induced by repetitive traumatic injury. Many affected individuals often have a history of manual labor or repetitive motion tasks (shoveling, pulling) that would involve the musculature of the upper back. Elastofibromas generally reach a relatively large size (5 to 10 cm) before patients seek medical attention. Although elastofibromas are usually painless, they may often cause some limitations in range of motion. Elastofibromas are probably more common than realized. They often present as incidental findings on imaging studies performed for an unrelated reason. Elastofibromas are completely benign. If they cause dysfunction, they can be removed surgically with a marginal or lesional excision without risk of recurrence. There is some suggestion that there may be a familial predisposition to the development of elastofibroma. Elastofibromas are very bland histologically. They comprise a mixture of normal fat and hypocellular fibrous tissue (Figure 6.2.2). The key feature for diagnosis is the presence of large, fragmented elastic fibers. On regular hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections, these are easily overlooked and may appear as very subtle pink strands or globules of pink material (Figures 6.2.3 and 6.2.4). Careful search reveals thick, deeply eosinophilic fragmented elastic fibers (Figures 6.2.5 and 6.2.6). Histochemical stains for elastin can be helpful in highlighting the degenerated fibers (Figure 6.2.6). These take the form of short thick strands or dots of degenerated elastin. Some histologic variations of elastofibroma include focal myxoid and cystic degenerative change. FIGURE 6.2.1 This location between the scapula and thoracic wall is classic for elastofibroma. FIGURE 6.2.2 Elastofibroma is poorly defined and often appears as fibrous tissue infiltrating normal fat. FIGURE 6.2.3 At first glance, the degenerated fibers of elastofibroma can be easily overlooked. The involved soft tissue has an overall degenerative, myxoid-appearing character. FIGURE 6.2.4 Longitudinal fragments of degenerating elastin are identified as coarse fibers. FIGURE 6.2.5 In the perpendicular plane, the elastin fibers appear as pink dots or large globules. FIGURE 6.2.6 An elastin stain highlights the abnormal elastic fibers. Fibromatosis encompasses both superficial and deep (desmoid fibromatosis) forms of lesions. Superficial fibromatoses frequently occur in the palms of the hands and the plantar surfaces of the feet. In the former location, they are frequently termed Dupuytren disease. The superficial fibromatoses are fairly common, affecting an estimated 20% of the population at some point in life. In these locations, they may cause bumps or even contractures, which are amenable to surgical correction. Deep fibromatosis, or desmoid tumor, represents a more difficult problem. It occurs most commonly in adults, although there is also a pediatric form of the lesion. This is a diffusely infiltrative process, which is linked to dysregulation of the Wnt signaling pathway. Fibromatosis may be difficult to completely eradicate, and many patients suffer from multiple recurrences and significant morbidity despite the nonmetastasizing nature of this lesion. Adult forms of fibromatosis can be simplistically divided into sites of involvement: abdominal wall (classic desmoid tumor) and intra-abdominal and extra-abdominal locations. In the abdominal wall, desmoid typically occurs in young women following pregnancy. This classic presentation has led to speculation that hormonal and/or traumatic stimuli may facilitate the growth of the lesion. In extra-abdominal locations, fibromatosis occurs in a multitude of sites, including the extremities, trunk, and head and neck regions (Figure 6.3.1). Growth is slow, insidious, and usually painless. Patients may eventually seek medical attention because of deformity or limitation of range of movement. In intra-abdominal sites, fibromatosis occurs commonly in the mesentery but may also arise in the retroperitoneum and pelvis. These lesions may become very large before noticed by the patient. Often the lesion may present when it encroaches on some other organ or vital structure. Of note, a significant number of patients with intra-abdominal fibromatosis have a prior history of surgery. This may somehow provide a stimulus to formation of the lesion in individuals who may be prone to forming desmoids. Fibromatoses or desmoid tumors occur sporadically and in patients with Gardner syndrome. The latter is also known as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. Patients have a germline mutation of the APC gene located on 5q21. In addition to multiple colonic adenomas, they also have an increased incidence of fibromas, osteomas, and skin lesions. Treatment of fibromatosis is largely surgical. Even with complete surgical excision and negative histologic margins, recurrences are very common. Alternative therapies, including radiation, tamoxifen, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors can augment the standard surgical approach in patients who experience multiple recurrences. The differential diagnosis of fibromatosis in adults includes a number of other benign and low-grade spindle cell neoplasms. These are summarized in Table 6.3.1. Desmoid tumors form firm mass lesions that may appear circumscribed on gross inspection, but are microscopically infiltrative. At the periphery of the lesion, the leading edge entraps fat, fibrous tissue, and fragments of skeletal muscle (Figure 6.3.2). The overall cellularity of desmoid tumors can be highly variable. Some lesions appear very fibrous or hyalinized, resembling scar tissue (Figure 6.3.3). Others are more cellular and are comprised of fascicles of plump myofibroblast-type cells arranged in herringbone and storiform patterns. Small vessels can be identified throughout the lesion; these are relatively inconspicuous and normal in shape and caliber. The individual cells have indistinct cytoplasmic boundaries and open, vesicular nuclei (Figure 6.3.4). In more cellular lesions, mitotic figures may be prominent. Necrosis and atypical mitoses should not be identified in fibromatoses. Because the lesional cell is a myofibroblast, desmoids can express muscle markers such as desmin and actin when subjected to immunohistochemistry. As such, these markers are not useful in separating desmoid from some of its closest histologic mimics such as leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, nodular fasciitis (NF), and myofibroblastic sarcoma. When desmoid is suspected or in the differential of a low-grade fibroblastic lesion, immunohistochemical detection of beta-catenin can be useful. An estimated 70% to 80% of fibromatoses show an abnormal nuclear localization of beta-catenin, a feature particularly helpful in making a diagnosis of fibromatoses on small biopsy material (Figure 6.3.5). Because of the dense, fibrous nature of fibromatosis, it often yields unsatisfactory specimens on needle aspiration biopsy. When material is obtained, it tends to be hypocellular and comprised of very dense fragments of fibrous material with associated small spindled cells (Figure 6.3.6). There is rarely a single-cell population in aspirates of fibromatosis. When present, single cells appear as stripped nuclei in the background. Cytologic findings of desmoid tumors are nonspecific. The features described in the preceding overlap those of a number of lesions including scar and normal fibrous tissue. Again, demonstration of abnormal nuclear accumulation of beta-catenin can be very helpful in making a specific diagnosis of fibromatosis on small biopsy materials. FIGURE 6.3.1 This fibromatosis within the musculature of the posterior calf is diffusely infiltrative. FIGURE 6.3.2 Diffuse or aggressive fibromatosis often entraps fat and individual fibers of adjacent skeletal muscle. FIGURE 6.3.3 Fibromatosis is variable in overall cellularity. This example is extensively hyalinized and sclerotic to the point that it almost resembles a keloid. FIGURE 6.3.4 A more cellular example of fibromatosis. The individual tumor cells have very indistinct cytoplasmic boundaries and elongated, sometimes wavy, nuclei. The nuclei tend to have light chromatin and a single nucleolus. FIGURE 6.3.5 Immunohistochemical staining for beta-catenin. Most cases of fibromatosis show intense nuclear positive staining for this marker. FIGURE 6.3.6 Aspirates of fibromatosis are almost always very hypocellular. Rare fragments of dense stroma and bland spindle cells may be present. TABLE 6.3.1 Differential Diagnosis of Adult Benign and Low-Grade Spindle Cell Neoplasms* Neurofibroma is the one of the major subtypes of benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors (the other being schwannoma). Neurofibromas occur sporadically and in association with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). NF1 is caused by a mutation in the NF1 gene located on chromosome band 17q11.2 that encodes for a tumor suppressor protein known as neurofibromin. The germline mutation is inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder, but de novo mutations are common as well. Signs and symptoms of NF1, as well as severity of disease, are notoriously variable. In addition, there are many different phenotypic abnormalities: café au lait spots, axillary freckles, optic glioma, and Lisch nodules in the iris, in addition to neurofibromas. The requirements for a clinical diagnosis of NF1 and NF2 are summarized in Table 6.4.1. Two subtypes of neurofibroma (diffuse and plexiform) are more clearly linked to NF1, but affected patients often have solitary neurofibromas as well. In addition, individuals with NF1 are at risk for malignant degeneration of a preexisting neuroibroma, whereas individuals who do not have a mutation of the NF1 gene are not at risk. Neurofibromas can occur in any site, both deep soft tissues and superficial cutaneous lesions. They are usually painless, but may form an unpleasant-appearing polypoid mass beneath the skin. They are often excised for cosmetic purposes. Individuals with NF1 may have multiple neurofibromas that need excision for functional purposes as well as to exclude the possibility of malignant transformation. The solitary or localized form of neurofibroma is the most common. These are usually round- or fusiform-shaped masses that may or may not have an associated peripheral nerve. The latter phenomenon is more likely to be seen in deep-seated tumors and very rarely identified in association with superficial neurofibroma. Neurofibromas vary in their overall cellularity, some with compact cellular stroma and others with a more myxoid type of background. Unlike schwannomas, cystic degeneration is not a common feature. Neurofibromas frequently display a cellular pattern referred to as “shredded carrots.” This corresponds to the haphazard arrangement of Schwann cells with wavy cytoplasmic extensions (Figure 6.4.1). In addition, neurofibromas are often infiltrated by inflammatory cells and histiocytes. Nuclear atypia may be identified, similar to the “ancient changes” of schwannoma. The atypia is largely manifest as enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei, often with a “smudged” appearance to nuclear chromatin (Figure 6.4.2). Mitoses are usually not readily identified in solitary (benign) neurofibroma. Neurofibromas demonstrate immunohistochemical staining for S100 protein, but not as diffusely or strongly as in schwannomas. In addition, they often display CD34-positive fibroblasts as well as focal positive staining for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). As mentioned in the schwannoma section (Section 6.5), “hybrid” types of lesions, with features of both schwannoma and neurofibroma, are not uncommon. The second form of neurofibroma is the diffuse subtype. This subtype most commonly occurs in the subcutaneous tissues of the trunk or head and neck regions of young adults (Figure 6.4.3). Again, this lesion is more closely linked to NF1 than the solitary subtype, but unlike the plexiform pattern of neurofibroma, it is not pathognomonic for NF1. Unlike solitary neurofibromas, these are ill defined and extremely infiltrative. They tend to infiltrate around the adnexal structures of the skin and can cause extensive thickening of the dermis. This type of neurofibroma also likes to travel along fascial planes and insinuates itself into subcutaneous fat in the same manner as fibromatosis or dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (Figure 6.4.4). In the diffuse form of neurofibroma, the tumor cells tend to be small and relatively homogeneous. The cytoplasmic processes are indistinct, and cell nuclei are small and spindled or ovoid. Histologic variations include the presence of small whorled arrangements that resemble tactile elements as well as pigmented dendritic cells. The third and final subtype of neurofibroma is the plexiform subtype. Unlike the previous variants, this lesion is very closely linked to NF1 and is pathognomonic of the disease. Grossly, it is often compared to a “bag of worms” because of the irregular growth pattern of numerous nerve small nerve fascicles. Examination of histologic sections reveals multiple nodules of neural tissue, corresponding to different tissue planes or sections of the tumor bundles (Figure 6.4.5). Individual bundles of plexiform neurofibroma may have a myxoid central portion, but usually have a thin fibrous capsule at the periphery. The tissue between the bundles may be fibrous, fat, or additional neurofibromatous tissue in a more diffuse pattern. The plexiform variant of neurofibroma should be examined very carefully for evidence of malignant transformation. Individuals with plexiform neurofibroma by definition have NF1 and are at a small, but significant risk of developing malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. This often first manifests as focal nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia within one of the bundles or whorls of a plexiform neurofibroma. The cytologic features of neurofibroma are indistinguishable from those of schwannoma. Aspirates are of variable overall cellularity with a predominance of cohesive small tissue fragments (Figure 6.4.6). Individual cells have an indistinct cytoplasm, which has a tendency to imperceptibly merge with the background fibrous tissue. Individual intact cells are relatively rare. It is more common to see stripped or bare nuclear fragments in the background of a cytologic preparation of a neurofibroma. As with apsirates of schwannoma, aspirates from neurofibroma may show significant nuclear atypia. This is a normal variant of neurofibroma and should not be misinterpreted as malignancy. FIGURE 6.4.1 Solitary neurofibromas are highly variable in their overall cellularity. Most display small nuclei with comma or hook shapes embedded in a fibrous network. Some refer to this as a “shredded carrots” type of pattern. FIGURE 6.4.2 Like schwannoma, neurofibroma often displays nuclear atypia in the form of increased nuclear size and dark smudgy chromatin. The absence of mitotic activity is reassuring that this is a benign process. FIGURE 6.4.3 Diffuse type of neurofibroma that infiltrates between the adnexal structures of the skin. FIGURE 6.4.4 Diffuse neurofibroma also penetrates the deeper subcutaneous fat in a manner similar to dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans or fibromatosis. FIGURE 6.4.5 Plexiform neurofibroma, when sectioned, shows several different planes of the tumor. The appearance of this lesion has also been compared to a “bag of worms.” FIGURE 6.4.6 Aspirates of neurofibroma tend to be relatively hypocellular. Material is usually present as dense cohesive fragments of fibrous tissue with spindled cells attached. Rare stripped nuclei are often identified in the background. TABLE 6.4.1 Criteria for Neurofibromatoses Types 1 and 2 Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) The presence of two or more of the following features (cardinal clinical features): • Six or more cafe au lait macules >5 mm in size* • Two or more neurofibromas or one plexiform neurofibroma • Axillary freckling (Crowe sign) or inguinal region freckling • Optic glioma • Two or more Lisch nodules (iris hamartomas) • Osseous lesions: kyphoscoliosis, sphenoid dysplasia, cortical bone thinning, and others • A first-degree relative with NF1

DERMATOFIBROMA

CALCIFYING APONEUROTIC FIBROMA

NUCHAL FIBROMA

GARDNER FIBROMA

FIBROUS HAMARTOMA OF INFANCY

FIBROMA OF TENDON SHEATH

INCLUSION BODY FIBROMATOSIS

JUVENILE AND INFANTILE HYALINE FIBROMATOSIS

DESMOPLASTIC FIBROBLASTOMA

LIPOFIBROMATOSIS

HISTOPATHOLOGY

HISTOPATHOLOGY

CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

HISTOPATHOLOGY

CYTOLOGIC FEATURES

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree