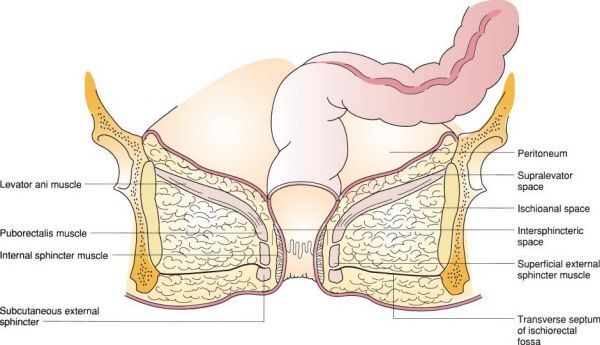

Anatomy of the anal canal. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Anatomy of the Anus

•The anal canal is a muscular tube

•Begins at the anorectal ring (the insertion of the levatorani muscles)

•Ends at the anal verge (the junction of the anoderm and the perianal skin)

•Cell types of the anal canal and anal transition zone include squamous, cuboidal, columnar epithelial cells, endocrine, and melanin-containing cells

•Does not have “transitional” cells

•The dentate line in the anal canal is approximately 2 cm from the anal verge

•Separates the proximal columnar epithelium from the distal squamous epithelium lining the anal mucosa

•At the dentate line, the anal glands drain their secretions into the anal canal

•Anoderm refers to the hairless squamous epithelium between the dentate line and the hair-bearing perianal skin (anal margin)

•The anoderm and perianal skin have somatic innervation and thus are sensitive to painful stimulation

•The external anal sphincter (EAS) is composed of skeletal muscle

•The striated skeletal muscle has three parts: Deep, superficial, and subcutaneous

•All layers are innervated by somatic sensory fibers from the pudendal nerve

•Is under voluntary control

•The internal anal sphincter is a continuation of the circular smooth muscle layer of the rectum

•Innervated with visceral sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers from presacral nerves

•Is constitutively contracted

A 54-year-old man has a complaint of daily bright red blood per rectum and protrusion from the anus after defecation that requires manual reduction. He uses fiber supplements but still strains with defecation. What is the diagnosis and treatment for this problem?

Hemorrhoidal disease manifests with the passage of bright red blood per rectum, protrusions from the anus, mucus drainage, pruritus, and/or anal discomfort.

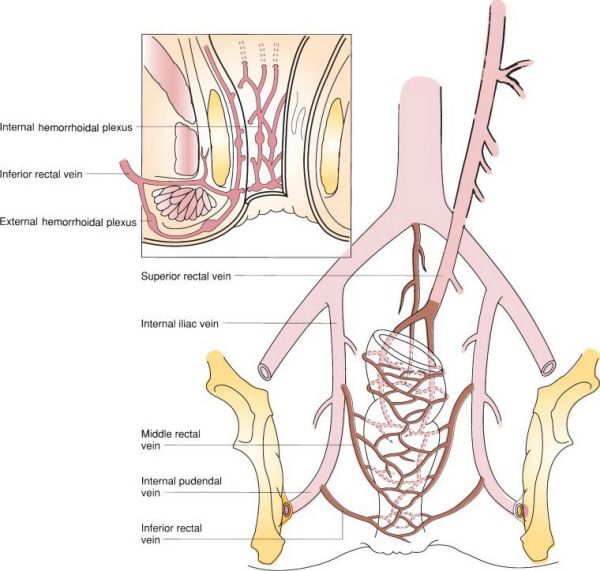

Venous drainage of the rectum and anal canal. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

•Hemorrhoids are tufts of vascular and connective tissue (vascular cushions) that are normally present in the anal canal

•There are two types of hemorrhoids: Internal and external

•Internal hemorrhoids are located proximal to the dentate line and have visceral innervation, therefore rarely cause anal pain

•Internal hemorrhoid disease is graded in the following manner:

•Grade 1: Bleeding without prolapse

•Grade 2: Prolapse with spontaneous reduction ± bleeding

•Grade 3: Prolapse requiring manual reduction ± bleeding

•Grade 4: Prolapse that is not reducible

•Grading is done by interpretation of the patients symptoms

•Treatment of internal hemorrhoid disease is directed by the grade of the disease

•Grade 1: Dietary fiber supplementation (e.g., psyllium, methylcellulose) and avoidance of straining; rubber-band ligation (RBL)

•Grade 2: As with Grade 1 but RBL required more frequently

•Grade 3/4: Hemorrhoidectomy (stapled or excisional)—resect down to the internal sphincter

•External hemorrhoids (skin tags)

•Located distal to the dentate line

•Are innervated with somatic fibers, thus usually cause pain if thrombosed

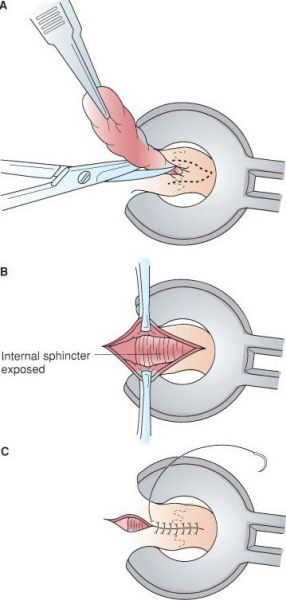

Excisional hemorrhoidectomy. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

•The vast majority of patients with grade 1 to 3 hemorrhoids do not seek treatment

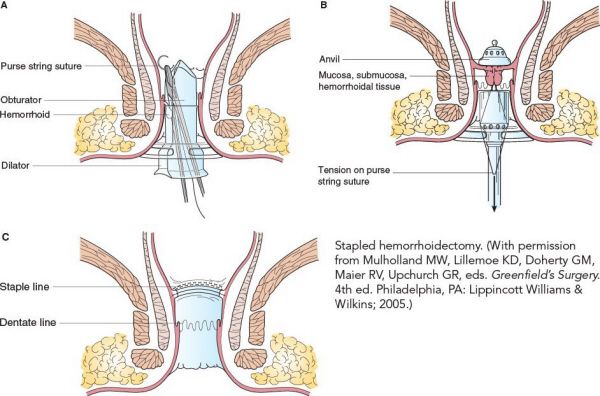

•Excisional and stapled hemorrhoidectomy procedures(for prolapsing hemorrhoids or PPH) have similar long-term efficacy

•The stapled technique is associated with decreased post-operative pain but can be complicated by, in rare incidences, severe persistent anal pain

Stapled hemorrhoidectomy. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Internal hemorrhoids usually present as painless bright red blood on the toilet tissue, and rarely are the cause of anal pain.

Thrombosed Hemorrhoid

•A blood clot in an external hemorrhoid causing acute pain

•If diagnosed within 1 to 2 days of pain onset, treat with incision and evacuation of the thrombus, or excision of the entire thrombosed skin tag

•When diagnosis is delayed 2 to 4 days after pain onset, treatment with warm soaks (“sitz baths”) and pain medications alone are effective

•In this case, the pain caused by excising the clot is generally greater than the pain from the resolving hemorrhoid so intervention should be avoided

A 49-year-old man has a complaint of 2 months of severe anal pain that occurs during a bowel movement and after wiping he notices bright red blood on the toilet tissue. What is the diagnosis and treatment for this problem?

An anal fissure is most likely the result of the passage of hard stool that tears the lining of the anal canal as it passes. The treatment is based on decreasing muscle tension.

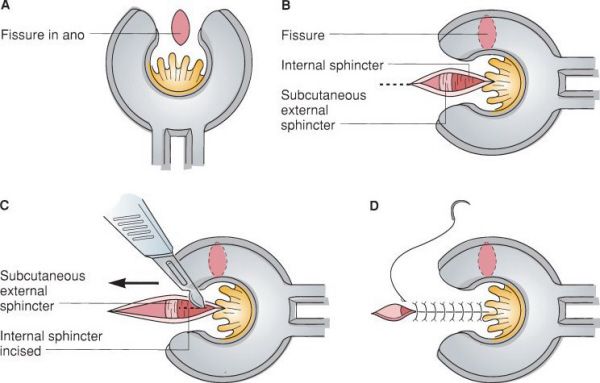

Lateral internal sphincterotomy. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Anal Fissure

•A painful ulceration in the anoderm from local trauma in the anal canal below the dentate line

•90% occur along the posterior midline

•With lateral or recurrent fissures, IBD should be considered

•Treatment begins with warm soaks (sitz bath), stool bulking agents (e.g., methylcellulose), nifedipine ointment (to relax increased sphincter tone), and topical anesthetics (e.g., lidocaine jelly)

•The next treatment option is topical nitroglycerine or nifedipine ointment

•Goal is to relax the sphincter muscle to increase blood supply to the mucosa to improve healing

•Nitroglycerine treatment is more likely to be successful with an acute fissure (<2 months) rather than a chronic fissure

•Botulinum toxin injection is an option for treating chronic anal fissures

•Lateral internal sphincterotomy is the surgical treatment of choice for anal fissures refractory to “conservative” management

•To decrease the risk of incontinence, the fistulotomy should be tailored to the size of the fissure

•Fissures secondary to IBD should NOT undergo surgical treatment. In general this type of fissure is not as painful as a non-IBD related fissure.

•If a fissure fails to heal or looks atypical, biopsy should be considered to rule out malignancy

The most common reason for persistent anal pain following a left internal sphincterotomy is that the sphincterotomy was inadequate.

A 34-year-old man presents with 3 days of perianal pain and swelling. Examination reveals a tender, cellulitic lesion involving the skin adjacent to the anus. What is the diagnosis and treatment?

An anoperineal abscess occurs when anal gland drainage is occluded, resulting in an infection of the gland and abscess formation. Antibiotics are reserved for those patients with an increased risk for an infectious complication.

Anatomy of perianorectal spaces. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Anoperineal Abscess

•The abscess is labeled according to its location around the anus or rectum

•Perianal abscess: In the soft-tissue overlying the sphincter complex

•Intersphincteric abscess: Between the internal and external sphincters

•Ischioanal abscess: In the ischioanal space

•Supralevator abscess: Between the levators and the overlying peritoneum

•Treatment is incision and drainage (I&D) of the abscess. Patients should NOT be treated with antibiotics alone.

•Adequate drainage can be achieved via a small “stab” incision and insertion of a mushroom-type drain into the abscess cavity

•The incision should be made as close to the anal verge as possible to prevent formation of a long-track fistula-in-ano (FIA)

•The drain is left for 7 to 10 days

•Large or deep abscesses may require I&D under general anesthesia

•Antibiotics are indicated for individuals with immunosuppression, diabetes, prosthetic implants, as well as valvular or developmental cardiac defects

•Patients should be counseled that they could develop a subsequent perianal fistula

A FIA and a recurrent abscess are the main complications following an I&D procedure.

A 34-year-old man presents 3 months after incision and drainage of an ischioanal abscess complaining of discharge from a fleshy lump near his anus. What is his diagnosis and how is this treated?

A FIA is often managed with seton placement or a fistulotomy procedure.

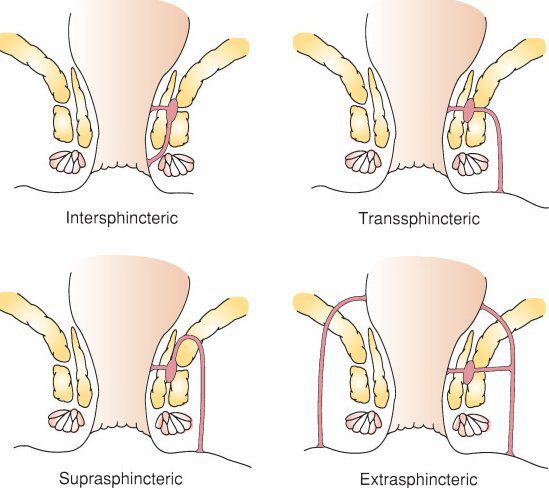

Types of fistula-in-ano. (With permission from Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR, eds. Greenfield’s Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Fistula-in-ano

•An abnormal connection between the lumen of the anus (or rectum) and the perianal skin

•Most often, the internal opening of the FIA is at the dentate line

•Presents with drainage of mucus or flatus from a skin opening (external opening)

•The external opening often corresponds with the drainage site of a previous abscess

•May be associated with an abscess, prior anal surgery, Crohn’s disease, radiation, or cancer

•An examination under anesthesia (EUA) may be necessary to identify the anatomy

•The “Parks classification” defines FIA by their relationship to the anal sphincters

•Intersphincteric FIA: Tracks between the internal anal sphincter (IAS) and EAS

•

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree