Fig. 1.1

Sagittal plane view of the prostate gland. (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2014, all rights reserved)

Coronal sections along the course of the ejaculatory ducts and distal (apex to mid-gland) urethral segment demonstrate the anatomic relationships between the two major glandular zones of the prostate, the peripheral and central zones [1]. The peripheral zone (PZ) comprises about 65 % of glandular prostatic mass and its ducts exit bilaterally from the posterior urethral wall at the verumontanum to the prostate apex with branches that curve anteriorly and posteriorly. The central zone (CZ) comprises about 30 % of the glandular prostate , with ducts branching from the verumontanum (mid-gland) and fanning out toward the base, in a flattened conical arrangement, to surround the ejaculatory duct orifices. Oblique coronal sections along the proximal (mid to base) prostatic urethra from verumontanum to bladder neck best define the transition zone (TZ), which normally encompasses about 5 % of the prostatic glandular tissue [2]. This zone is formed by two small lobes whose ducts leave the posterolateral urethral wall and curve anteromedially. The main nonglandular tissue of the prostate is the anterior fibromuscular stroma, which overlies the urethra in the anteromedial prostate. Its bulk and consistency vary considerably from apex to base. McNeal considered this stroma as a wedge-shaped stromal barrier, shielding the prostatic urethra and glandular zones from overlying structures [4].

As McNeal’s dissections in various planes were conducted in autopsy specimens, they likely reflect the cone-shaped organ seen in vivo. In contrast, radical prostatectomy specimens are typically spherical, owing to surgical manipulation, tissue contraction at removal and subsequent processing. Sectioning from apex to base in the anterior-posterior fashion common in surgical pathology practice yields topography that varies from McNeal’s descriptions. Recent studies of whole mounted, serially sectioned and totally embedded radical prostatectomy specimens have highlighted underappreciated histopathologic features of glandular and stromal prostatic anatomy [5, 6].

Anatomy of the Prostate Gland in Surgical Pathology Specimens: Histologic Variation by Anatomic Region

Apical One Third of the Prostate (Apex)

In a surgical pathology specimen sectioned from anterior to posterior, the apical (distal) urethra is located near the center of the section (Fig. 1.2). Tissue shrinkage due to formalin fixation and processing artifactually shortens the distance from prostatic apex to verumontanum and everts the posterior peri-urethral tissue into the urethral space. These effects create an artificial “promontory” in the apical portions of the gland. The urethra is immediately surrounded by a thin stroma and variable number of peri-urethral glands, which intermingle anteriorly with a semicircular band (“sphincter”) of compactly arranged and vertically oriented muscle fibers. This semicircular band is incomplete posterior to the urethra, appearing as a densely eosinophilic, aglandular, muscular column extending posteriorly from the urethra and serving as an important histopathologic landmark for apical prostatic tissue.

Fig. 1.2

Whole mount section from apex of prostate. The urethra and promontory (P) are central and proceeding anteriorly, the semicircular sphincter (SCS) and anterior fibromuscular stroma (AFMS) are visualized. The posterior, lateral, and anterolateral portions of the apex are composed of peripheral zone (PZ) tissue. Most anteriorly, the anterior extraprostatic space (AEPS) contains vascular and adipose remnants of the dorsal vascular complex

Further anterior to the semicircular muscle, the anterior fibromuscular stroma , intertwined at the apex with skeletal muscle fibers of the urogenital diaphragm, traverses horizontally and laterally and extends to the anterior- and apical-most aspects of the prostate. Unlike in the posterior and posterolateral prostate , the “prostatic capsule” is incomplete at the prostatic apex, anterior and anterolaterally, lacking a definitive border. Hence, the task of separating prostatic from extraprostatic tissue can be challenging in these regions of the gland. While heightened intraprostatic pressure may cause bulging of hypertrophic TZ acini, no normal TZ tissue is located in the prostatic apex. The bilateral PZ, which composes essentially all of the glandular tissue at the apex, occupies the posterior, lateral, and anterolateral prostate, abuts the anterior fibromuscular stroma medially and forms a nearly complete ring [5].

Middle One Third of the Prostate (Mid-Gland)

The key anatomic landmark in the mid-gland is the verumontanum, the exaggerated area of glandular-stromal tissue, located subjacent to the posterior urethral wall, into which the ejaculatory ducts insert and from which the glandular zones arise [4]. The verumontanum was identified by McNeal as the point of a 35° angulation, which divides the urethra into proximal (toward the base) and distal (toward the apex) segments. At mid-gland, the TZ emerges as bilateral lobes in the anteromedial region. In whole mount sections, the TZ ducts can be identified coursing anterolaterally from the posterior urethra to serve as a boundary between transition and PZs . In prostates without significant benign prostatic hypertrophy, the PZ still composes the posterior, lateral, and the majority of anterolateral tissue at the mid-gland (Fig. 1.3a). When benign processes including hypertrophy and adenosis prominently involve the TZ, the anterolateral “horns” of the PZ may be significantly compressed toward the lateral-most portions of the gland (Fig. 1.3b). In the mid-prostate, the anterior fibromuscular stroma may be fused with skeletal muscle fibers (of levator ani origin) as well, but may be less evident due to increased glandular density and the effects of organ contraction [5, 6].

Fig. 1.3

a Whole mount section from mid-prostate at the level of the verumontanum (V). Note the bilobed transition zone (TZ) arising from elongated ducts (D), which course anteromedially. The peripheral zone (PZ) still occupies the posterior, lateral, and anterolateral portions of the gland, with a cancer nodule (CA) evident in the right anterior peripheral zone. In the mid-prostate, the anterior fibromuscular stroma (AFMS) is much condensed and the anterior extraprostatic space (AEPS) largely retains its apical content. b Whole mount section from mid-prostate at the level of the verumontanum (V) in a gland with extensive benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH). Anterolateral “horns” of the peripheral zone (PZ) are compressed laterally by the expanded transition zone tissue and the anterior fibromuscular stroma (AFMS) is diminished in extent

Basal One Third of the Prostate (Base)

From mid-gland to base, the urethra is progressively invested by a thick layer of short smooth muscle fibers, constituting the “preprostatic sphincter,” thought to function during ejaculation to prevent retrograde flow of seminal fluid and to maintain resting tone that ensures closure of the proximal urethral segment [2]. At the base, TZ glands gradually recede and few remaining PZ acini once again comprise the anterior glandular tissue. Unlike at the apex, PZ glands rarely extend anteromedially due to the vast stroma in this region. This stroma appears as an expansive swath of tissue comprised of both preprostatic sphincter and anterior fibromuscular stroma , with the latter often merging anteriorly with large smooth muscle bundles located in the anterior extraprostatic space (Fig. 1.4). With increasing angulation, the prostatic urethra is identified further anteriorly in histologic sections, eventually breaching the anterior-most border of tissue sections at the level of the bladder neck , a region which also contains no clear “capsule.” Posterior to the urethra, the ejaculatory ducts emerge and are immediately encircled by a sheath of fibrous tissue with abundant lymphovascular spaces. Posterolaterally, central zone glands surround the ejaculatory duct sheath. In the most basal portions of the gland, the distinct muscular coat at the base of the seminal vesicles forms and separates from the bulk of the prostatic tissue creating a fibroadipose tissue septum. The last vestiges of the central zone are present at the most lateral aspects of the emerging seminal vesicles [5, 6].

Fig. 1.4

Whole mount section from base of prostate. The preprostatic sphincter (PPS) is evident as a pale area surrounding the proximal urethra. The transition zone (TZ) shows abortive small acini and is covered anteriorly by a vast anterior fibromuscular stroma (AFMS), which merges with smooth muscle bundles in the anterior extraprostatic space (AEPS). Posteriorly, the expansive central zone (CZ) surrounds the ejaculatory duct complex (EJD), while some peripheral zone (PZ) is still apparent laterally

Extraprostatic Tissue

In vivo, the tissue immediately anterior to the prostate is the dorsal venous or vascular complex, a series of veins and arteries set in fibroadipose tissue that runs over the anterior prostate and continues distally to supply/drain the penis. At radical prostatectomy , the complex is ligated and divided, with a portion of the blood vessels and fibroadipose tissue adhering to the prostate specimen. These are identified in the anterior extraprostatic tissue from apex through mid-gland (Fig. 1.3a, 1.3b), while the most proximal (basal) 2–3 sections reveal medium- to large-sized smooth muscles’ bundles admixed with adipose tissue [5, 6]. These fibers are morphologically identical to those of the muscularis propria (detrusor muscle) of the bladder and probably represent a detrusor muscle extension over the prostatic base to mid-gland (Fig. 1.4).

Over the medial half of the posterior surface of the prostate, the “capsule” is thickened by its fusion to Denonvilliers’ fascia, a thin collagenous membrane whose smooth posterior surface rests directly against the muscle of the rectal wall. The prostatic “capsule” is fused to the fascia with an interposed adipose layer containing a variable number of smooth muscle fibers. These smooth muscle fibers may cause confusion in determining the presence of extraprostatic extension as they complicate assessment of the outer border of the prostate [6].

Clinical and Diagnostic Significance of Prostatic Anatomy and Histomorphology

Clinicopathologic Features and Pathologic Outcomes of Anterior Prostate Cancers

Since the late 1980s, a number of authors have argued that TZ tumors could be identified using distinctive histomorphologic criteria [7]. McNeal and colleagues described “clear cell” histology [8] as discrete glands of variable size and contour, composed of tall cuboidal to columnar cells with clear-to-pale pink cytoplasm, basally oriented nuclei, and occasional eosinophilic luminal secretions (Fig. 1.5). In a small series, McNeal et al. demonstrated that this morphology predominated in up to two thirds of TZ-dominant cancers and nearly 75 % of incidental small TZ tumors diagnosed on transurethral resection specimens and was associated with a high percentage of Gleason pattern 1–2 cancer foci. It was concluded that this “clear cell” appearance was a marker of TZ tumors and more globally, of low-grade lesions [8].

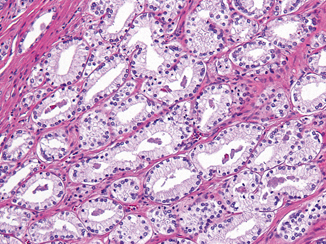

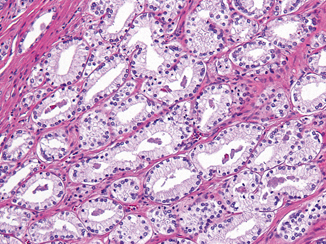

Fig. 1.5

Clear cell histology with variably shaped glands displaying pale cytoplasm and basally oriented nuclei

Nearly two decades later, Garcia et al. studied dominant prostatic lesions from both the peripheral and TZs and confirmed that this tumor appearance is present to some extent in the majority of TZ tumors and was more commonly the predominant morphology in TZ tumors than in PZ tumors (ratio > 5:1). However, they also found that “clear cell” histology is the predominant morphology in only 50 % of TZ-dominant tumors [9]. A careful look at McNeal’s original work reveals that 51 % of PZ-dominant tumors exhibited some “clear cell” histology, with 21 % of these showing ≥ 20 % [8]. Garcia et al. similarly found that 43 % of PZ-dominant tumors displayed some “clear cell” histology and that 35 % of these showed > 25 % [9].

The finding of nonfocal “clear cell” morphology in peripheral-zone dominant prostate cancers is relevant to assignment of zonal origin for prostate cancer. The significant degree of variability in anterior prostatic anatomy described earlier—specifically, the proportions of PZ and TZ tissues in this region from apex to base—may engender difficulty in assessing zone of origin. In such cases with anatomic complexity, finding 25–50 % (nonfocal) “clear cell” histology in an anterior tumor will not help establishing its zonal origin. It has also been shown that the presence or absence of “clear cell” histology in needle biopsy specimens does not correlate with the presence of TZ tumor at radical prostatectomy [10].

Most studies that have compared tumors of TZ and PZ origin have ascribed a more indolent course, higher cure rate, and overall more favorable prognosis for TZ tumors when compared with PZ tumors [7, 11–13]. Although larger volumes and higher serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) values have been described for TZ tumors, most reports have maintained that TZ tumors show significantly lower Gleason scores . However, classification of TZ cancers was often founded upon recognizing “clear cell” histology and these TZ tumors were compared with posterior PZ cancers. Until recently, few studies have compared TZ tumors with those arising in the anterior PZ, the predominant glandular tissue of the apical prostate.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree