Chapter 35

Alterations of Pulmonary Function

Valentina L. Brashers and Sue E. Huether

Clinical Manifestations of Pulmonary Alterations

Signs and Symptoms of Pulmonary Disease

Dyspnea

Dyspnea is a subjective experience of breathing discomfort that is comprised of qualitatively distinct sensations that vary in intensity. The experience derives from interactions among multiple physiologic, psychologic, social, and environmental factors, and it may induce secondary physiologic and behavioral responses. It is often described as breathlessness, air hunger, shortness of breath, increased work of breathing, chest tightness, and preoccupation with breathing.1 Dyspnea may be the result of pulmonary disease or many other conditions, such as pain, heart disease, trauma, and anxiety.

The severity of the experience of dyspnea may not directly correlate with the severity of underlying disease.2,3 Either diffuse or focal disturbances of ventilation, gas exchange, or ventilation-perfusion relationships can cause dyspnea, as can increased work of breathing or diseases that damage lung tissue (lung parenchyma). One proposed mechanism involves an impaired sense of effort where the perceived work of breathing is greater than the actual motor response generated. Stimulation of many receptors can contribute to the sensation of dyspnea including mechanoreceptors (the stretch receptors, irritant receptors, and J-receptors), upper airway receptors, and central and peripheral chemoreceptors that interact with the sensory and motor cortex.4,5

The more severe signs of dyspnea include flaring of the nostrils, use of accessory muscles of respiration, and retraction (pulling back) of the intercostal spaces. In dyspnea caused by parenchymal disease (e.g., pneumonia), retractions of tissue between the ribs (subcostal and intercostal retractions) are observed more often than supercostal retractions (retractions of tissues above the ribs), which predominate in upper airway obstruction. Retractions of any type are more commonly seen in children or in adults who are thin and have poorly developed thoracic musculature. Dyspnea can be quantified by the use of ordinal rating scales or visual analog scales.3

Cough

Cough is a protective reflex that helps clear the airways by an explosive expiration. Inhaled particles, accumulated mucus, inflammation, or the presence of a foreign body initiates the cough reflex by stimulating irritant receptors in the airway. There are few such receptors in the most distal bronchi and the alveoli; thus it is possible for significant amounts of secretions to accumulate in the distal respiratory tree without cough being initiated. The cough reflex consists of inspiration, closure of the glottis and vocal cords, contraction of the expiratory muscles, and reopening of the glottis, causing a sudden, forceful expiration that removes the offending matter. The effectiveness of the cough depends on the depth of the inspiration and the degree to which the airways narrow, increasing the velocity of expiratory gas flow. Stimulation of cough receptors is transmitted centrally through the vagus nerve, and central modulation of the cough reflex can be influenced by opiates and serotonergic agents.6,7 Cough occurs frequently in healthy individuals; however, those with an inability to cough effectively are at greater risk for pneumonia.

Acute cough is cough that resolves within 2 to 3 weeks of the onset of illness or resolves with treatment of the underlying condition. It is most commonly the result of upper respiratory tract infections, allergic rhinitis, acute bronchitis, pneumonia, congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolus, or aspiration. Chronic cough is defined as cough that has persisted for more than 3 weeks, although some researchers have suggested that 7 or 8 weeks is a more appropriate timeframe because acute cough and bronchial hyperreactivity can be prolonged in some cases of viral infection. In nonsmokers, chronic cough is commonly caused by postnasal drainage syndrome, nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis, asthma, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or heightened cough reflex sensitivity.8 In smokers, chronic bronchitis is the most common cause of chronic cough, although lung cancer must always be considered. Individuals taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for hypertension may develop chronic cough that resolves with discontinuation of the drug.

Abnormal Sputum

Hemoptysis usually indicates infection or inflammation that damages the bronchi (bronchitis, bronchiectasis) or the lung parenchyma (pneumonia, tuberculosis, lung abscess). Other causes include cancer and pulmonary infarction. The amount and duration of bleeding provide important clues about its source. Bronchoscopy, combined with chest computed tomography (CT), is used to confirm the site of bleeding.9

Abnormal Breathing Patterns

Cheyne-Stokes respirations are characterized by alternating periods of deep and shallow breathing. Apnea lasting 15 to 60 seconds is followed by ventilations that increase in volume until a peak is reached, after which ventilation (tidal volume) decreases again to apnea. Cheyne-Stokes respirations result from any condition that slows the blood flow to the brainstem, which in turn slows impulses sending information to the respiratory centers of the brainstem. Neurologic impairment above the brainstem is also a contributing factor (see Table 17-4 and Figure 17-1).

Hypoventilation and Hyperventilation

Hypoventilation is inadequate alveolar ventilation in relation to metabolic demands. It is caused by alterations in pulmonary mechanics or in the neurologic control of breathing such that minute volume (tidal volume × respiratory rate) is reduced. When alveolar ventilation is normal, carbon dioxide (CO2) is removed from the lungs at the same rate at which it is produced by cellular metabolism. This maintains arterial CO2 pressure (Paco2) at normal levels (40 mmHg). With hypoventilation, CO2 removal does not keep up with CO2 production and Paco2 increases, causing hypercapnia (Paco2 greater than 44 mmHg). (Table 34-2 contains the definition of gas partial pressure and other pulmonary abbreviations.) This results in an increase in hydrogen ion in the blood, termed respiratory acidosis, which can affect the function of many tissues throughout the body.

Hypoventilation is often overlooked until it is severe because breathing pattern and ventilatory rate may appear normal. Blood gas analysis (i.e., measurement of the Paco2 of arterial blood) reveals the hypercapnia. Pronounced hypoventilation can cause somnolence or disorientation. In addition, alveolar hypoventilation with hypercapnia results in secondary hypoxemia because the accumulation of alveolar CO2 displaces oxygen (see Hypercapnia, p. 1251).

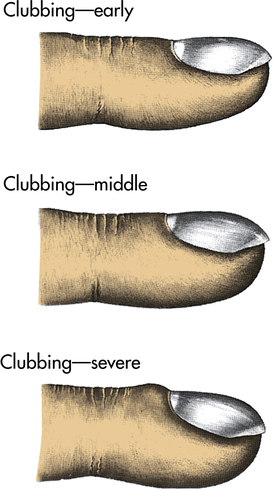

Clubbing

Clubbing is the selective bulbous enlargement of the end (distal segment) of a digit (finger or toe) (Figure 35-1) whose severity can be graded from 1 to 5 based on the extent of nail bed hypertrophy and the amount of changes in the nails themselves. It is usually painless. Clubbing is commonly associated with diseases that interfere with oxygenation, such as bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, pulmonary fibrosis, lung abscess, and congenital heart disease. It is rarely reversible with treatment of the underlying pulmonary condition. It can sometimes be seen in individuals with lung cancer even without hypoxemia, because of the effects of inflammatory cytokines and growth factors (hypertrophic osteoarthropathy).10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree