Alterations in Male Genital and Reproductive Function

Marvin Van Every

Key Questions

• What are the common causes of and clinical findings in priapism?

• What are the common causes of primary and secondary impotence?

• How can benign prostatic hyperplasia be distinguished from prostate cancer?

• What clinical manifestations are indicative of prostatic enlargement?

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Copstead/

The male genital system is susceptible to numerous congenital, acquired, and infectious conditions and, to a lesser extent, neoplasms. These disorders may interrupt the normal functions of urinary excretion and sexual function and fertility and directly affect the quality of life. This chapter will identify and explain the most common conditions that come to the attention of practitioners.

Disorders of the Penis and Male Urethra

Congenital Anomalies

Micropenis

Micropenis is defined as a small, normally formed penis with a stretched length more than two standard deviations below the mean.1 The normal range in newborns is 2.0 to 3.5 cm, so micropenis may be defined as a stretched length of less than 1.9 cm.2

Etiology and pathogenesis

Penile development and growth are both testosterone dependent. Therefore, micropenis may result from defects in testosterone production or a deficiency that results in poor growth of the organs that are targets of this hormone.

Diagnoses and treatment

Patients with micropenis must be evaluated for endocrine abnormalities. To check for these, one should measure serum levels of testosterone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). Depending on the results of these measurements, the problem may be determined to involve the hypothalamic-pituitary axis (Prader-Willi and Kallmann syndromes) or to be some form of a testicular disorder (Klinefelter syndrome).3

Treatment depends on administering testosterone, either intramuscularly (IM) or topically, to stimulate penile growth. Such treatment requires caution because growth may be altered by premature closure of the epiphyseal growth plates in the long bones. In rare cases, when micropenis fails to respond to testosterone, a female sex assignment is indicated.3

Urethral Valves

The vast majority of urethral valves are posterior in location and occur in the distal prostatic urethra. They are the most common cause of urinary obstruction in male newborns and infants. These valves are mucosal folds that resemble thin membranes and cause obstruction when the child attempts to void (Figure 31-1).

Etiology

Many theories have been given to explain how valves develop. It has been suggested that several different processes may occur to form different posterior valves. Most commonly, posterior valves may result from abnormal insertion and persistence of the distal wolffian ducts. Less frequently, a persistent urogenital membrane may result in valves and obstruction.4

Clinical manifestations

Children with posterior valves may have variable degrees of obstruction. In the most severe cases, intrauterine renal failure may cause oligohydramnios (decreased amniotic fluid), pulmonary hypoplasia (incomplete lung development), and either stillbirth or extreme distress at the time of delivery. More frequently, inability to void is noted shortly after birth (normal voiding occurs within 48 hours after birth), or the infant has abdominal masses representing a thickened palpable bladder or hydronephrotic kidneys. Varying degrees of azotemia and renal failure occur with this scenario. Finally, urinary ascites (extravasated urine in the peritoneum) may result from a urinary leak that is usually difficult to localize. In an infant with abdominal distention, the diagnosis of urethral valves is confirmed by a plain abdominal radiograph showing the bowel “floating” in the center of the abdomen. Prenatal ultrasounds often suggest the diagnosis before birth so immediate evaluation and treatment can take place upon delivery.

Older infants with a urethral valve are less likely to have a palpable kidney or ascites. Rather, urinary tract infection, poor stream with straining to void, or occasionally hematuria may be present. Urethral valves in these older male infants may not produce much obstruction, thus making the diagnosis more difficult.5

Treatment

Management of posterior valves involves initial management of the metabolic abnormalities with appropriate fluid management and electrolyte replacement. In patients with a urinary tract infection, drainage of urine with a urethral or occasionally a suprapubic catheter is necessary. Finally, ablation of the valves with an endoscopic resectoscope should be performed. In infants, this step may be delayed and a cutaneous vesicostomy made to temporarily divert and drain the urine. This approach reduces the risk of traumatizing the infant’s delicate urethra, which may create urethral stricture disease.

Rarely, urethral valves are located anteriorly in the penile urethra. Valves in this location are a very rare congenital anomaly and most likely represent urethral dilation or a diverticulum proximal to the valve.6 Endoscopic resection will correct the problem.

Urethrorectal and Vesicourethral Fistulas

Etiology

Urethrorectal and vesicourethral fistulas are rare and almost always associated with an imperforate anus. Failure of the urorectal septum to develop completely leads to persistent communication between the rectum posteriorly and the urogenital tract anteriorly.

Clinical manifestations and treatment

Children with a urethrorectal or vesicourethral fistula may pass fecal material and gas through the urethra. If the anus has formed normally with an external opening, urine may drain through the rectum. The diagnosis is made with cystoscopy and contrast-enhanced radiography to delineate a blind rectal pouch or communication. Surgery is needed to resect the fistula and open the imperforate anus.

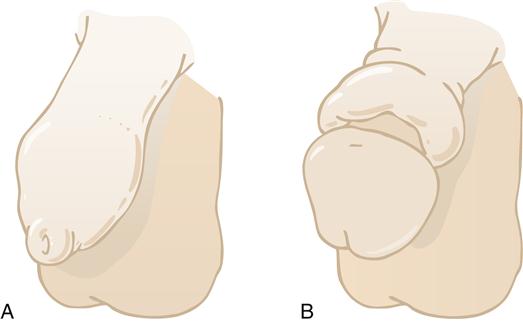

Hypospadias

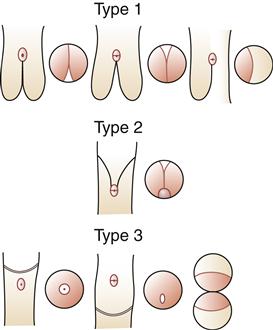

In hypospadias, the urethral meatus is located on the ventral undersurface of the penis or on the perineum (Figure 31-2). The condition may occur with varying degrees of severity. In the least severe cases, the meatus is located distally on the penis, either at the corona or on the undersurface of the glans. With increasing severity of the condition, the meatus assumes a more proximal location and is more often associated with chordee, or curvature of the penile shaft (Figure 31-3).

A, Glanular hypospadias. B, Subcoronal hypospadias. Note the dorsal hood of foreskin. C, Penoscrotal hypospadias with chordee. D, Perineal hypospadias with chordee and partial penoscrotal transposition. E, Megameatal variant of hypospadias diagnosed following circumcision; note absence of hooded foreskin. (From Kliegman RM et al: Nelson textbook of pediatrics, ed 19, Philadelphia, 2011, Saunders.)

Etiology and treatment

Hypospadias is the result of incomplete fusion of the urethral folds, so the meatus may be found anywhere along the phallus from the perineum to the glans. In the majority of cases hypospadias occurs distally, with about 85% of all cases involving the glans or corona.7 Because incomplete fusion of urethral folds may indicate insufficient masculinization, it is recommended that the more severe penoscrotal and perineal openings be evaluated for conditions of intersex.8

Management of hypospadias involves surgical repair. Many procedures are available, with several repairs indicated for each type of hypospadias. The goal of surgery is a good overall cosmetic appearance that will allow the patient to stand and direct his urinary stream and will also allow normal sexual function.

Epispadias

In epispadias, the urethra opens on the dorsal aspect of the penis at a point proximal to the glans (see Figure 31-2). Although much less common than hypospadias, it can be considerably more disabling.

Etiology and treatment

The embryogenesis of epispadias is related to another congenital condition, exstrophy of the bladder. In this condition, the abdominal wall fails to form below the level of the umbilicus. At birth, the back wall of the bladder is exposed to the external environment.9 The development of epispadias is simply a mild degree of exstrophy, with a deficiency of abdominal wall formation present inferiorly. Most commonly, the defect extends proximally to involve the urinary sphincter and results in urinary incontinence. Less commonly, the urethral meatus is located more distally along the dorsum of the penis and is accompanied by urinary continence because the sphincter is not affected (see Figure 31-3).

Management of exstrophy and proximal epispadias with incontinence is difficult and involves staged surgical procedures to reconstruct a continent bladder neck and a functional urethra. The less common distal epispadias is usually managed with tubular reconstruction procedures similar to those used for repair of hypospadias.

Acquired Disorders

Priapism

Priapism may be defined as a painful, persistent erection. The patient usually reports several hours of painful erection in which the corpora cavernosa are tense with congested blood. The corpus spongiosum and glans are characteristically soft and uninvolved.

Etiology and treatment

The causes of priapism are multiple. Most cases are idiopathic, with the next most common cause being sickle cell disease. Other etiologic factors include use of anticoagulant therapy, presence of diabetes mellitus or leukemia, and use of certain antidepressant medications.10 Recently, intracavernosal injection of vasoactive substances for the management of impotence has been noted to cause priapism. On a rare occasion, oral erectile dysfunction medications can cause priapism. Although multiple causes exist, the common abnormality is probably an obstruction of venous drainage resulting in the buildup of viscous, poorly oxygenated blood in the corpora.11 If the process is allowed to continue, fibrosis of the corpora cavernosa will eventually occur and may cause impotence.

Management of priapism may involve a combination of measures, depending on the cause and duration of the condition. Initial therapy for priapism secondary to sickle cell disease includes sedation and oxygen.12 For the management of priapism secondary to other causes, initial measures may include aspiration of blood from the corpora, as well as injection of α-adrenergic agents.13 If the priapism remains refractory to these initial measures, a surgical shunting procedure may be necessary in which a shunt is created between the erect corpora cavernosa and the detumesced corpus spongiosum.

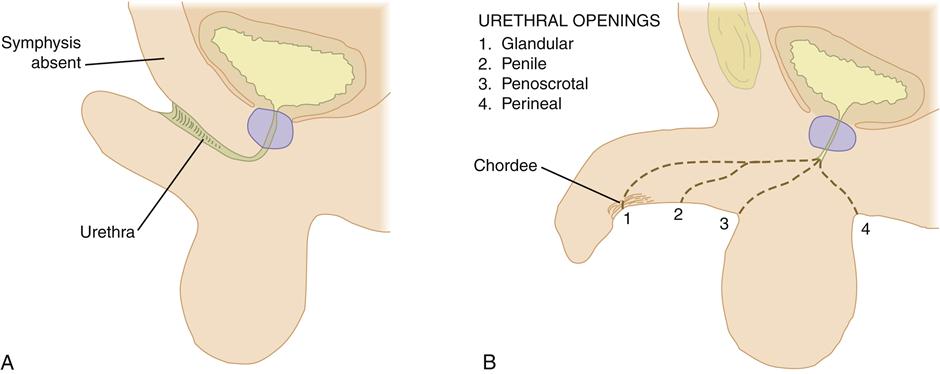

Phimosis and Paraphimosis

Etiology, clinical manifestations, and treatment

Phimosis occurs when the uncircumcised foreskin cannot be retracted over the glans of the penis (Figure 31-4, A). Phimosis is usually the result of chronic inflammation and infection from poor hygiene. Calculi and squamous cell carcinoma may occur, although it is usually the presence of erythema, tenderness of the phimotic foreskin, or a discharge that prompts the patient to seek medical attention.14 Management involves treating the infection with antifungal agents or antibiotics, followed by circumcision.

Paraphimosis, on the other hand, occurs when a foreskin that has been retracted over the glans up onto the shaft of the penis cannot be replaced in its normal position (see Figure 31-4, B). In this condition, which is usually secondary to chronic inflammation under the foreskin, a constricting ring of skin forms around the base of the retracted glans. The constriction causes venous congestion of the glans, with further swelling and edema making the condition worse. Treatment entails reducing the paraphimotic foreskin back over the glans, which can usually be accomplished by compressing the glans to reduce the edema. Occasionally, a slit or formal circumcision is needed to manage the problem.

Peyronie Disease

Etiology and treatment

Peyronie disease refers to the formation of palpable, fibrous plaque on the surface of the corpora cavernosa. This plaque subsequently causes curvature of the penis with painful, incomplete erections. No satisfactory treatment for this disease is available, although some cases may remit with time. Conservative therapies that have had limited success include the use of vitamin E or aminobenzoate potassium (Potaba), colchicine, and pentoxifylline (Trental). In addition, several operative procedures have been developed. These procedures involve excising the plaque and repairing the corporal defect with a graft or plicating the corporal bodies.15

Urethral Strictures

Etiology

Urethral strictures are fibrotic narrowings of the urethra and are usually composed of scar tissue. Most acquired strictures are due to a prior infection such as gonorrhea or trauma. Traumatic causes can be both iatrogenic, such as large urethral catheters and instrumentation, and noniatrogenic, such as straddle injuries.

Clinical manifestations and treatment

A decreased urinary stream is the most common complaint. Other common complaints include urethral discharge, infection, and urine retention. Urethral strictures are usually diagnosed by cystoscopy or retrograde urethrography, which would demonstrate a narrowing of the urethra. Management of urethral strictures involves procedures to dilate, incise, or reconstruct the urethra, depending on the extent and duration of the stricture.

Erectile Dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is the inability to achieve or maintain an erection sufficient for satisfactory sexual performance.17 It is highly prevalent in aging men, affecting approximately 50% of men older than 60 years of age.16 Its prevalence and incidence are highly connected with risk factors such as hypertension, elevated cholesterol level, presence of diabetes mellitus and/or metabolic syndrome, and lifestyle choices such as smoking, obesity, and lack of exercise.18

The physiologic process of penile erection is a complex interaction of the vascular, hormonal, and neurologic systems. Impotence may be primary or secondary. Primary impotence refers to the inability to attain an erection throughout life and is often related to deep-seated psychiatric problems of some duration. Occasionally, vascular trauma sustained during early childhood or adolescence may account for primary impotence.18

There are many causes of secondary ED ranging from psychogenic to traumatic. As our knowledge of the disease has advanced, we understand that most ED is due to physiologic changes in the vasculature of the corporal bodies of the penis. These changes may be due to surgery (e.g., radical prostatectomy or cystectomy), trauma (penile or neurologic), disease (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, pelvic irradiation, hyperlipidemia, hypogonadism), and aging.19

Etiology

Far more common than primary impotence is secondary impotence. An individual with secondary impotence is no longer able to achieve normal erections but did have normal erections in the past. The causes of secondary impotence are multiple and may be discovered by examining the patient’s medical history. Common causes of secondary impotence are peripheral vascular disease, the use of certain medications, endocrine problems, trauma, iatrogenic causes, and psychological causes. To differentiate organic causes from psychogenic impotence, one relies on the history, physical, and basic laboratory testing such as measurement of serum glucose and testosterone levels. Penile tumescence testing can also be utilized to make this distinction.

Arterial insufficiency of the penis may occur from obstruction of the arterial supply. Several processes may account for this obstructive arteriosclerosis. Stenosis of the arteries secondary to atheromatous plaque may be the most common etiologic factor. Diabetes mellitus not only may result in occlusion of arterial vessels but also may cause a neuropathy of the pudendal nerve that might result in erectile dysfunction.20 Most investigators have suggested that erectile dysfunction may result from excessive venous drainage from the penis. This occurs because the blood is not adequately trapped in the corpora.

The list of medications that may cause erectile dysfunction is long. Several antihypertensive agents, including propranolol, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and thiazides, have been associated with varying degrees of impotence. Other medications linked to erectile dysfunction include phenothiazines, antihistamines, and some antidepressants.21

Endocrinopathy accounts for a small percentage of impotence cases.22 Pituitary dysfunction resulting in decreased or no secretion of luteinizing hormone may result in decreased secretion of testosterone. Primary failure of the testes may also occur, resulting in decreased secretion of testosterone. Finally, excessive secretion of the hormone prolactin by the pituitary gland may result in low testosterone levels.

Trauma to the penis resulting in penile fractures and damage to penile erectile tissue may occasionally lead to partial or complete impotence. More common injuries include pelvic fractures with subsequent damage to the penile vascular and nervous supply. Iatrogenic trauma secondary to several commonly performed operations, including aortoiliac vascular surgery, and radical pelvic cancer operations may also result in impotence.

A newer concept in erectile dysfunction is the idea of vascular endothelial damage, which can be diffuse throughout the body. Some researchers believe impotence may be an indicator of coronary artery disease.

Finally, it must be remembered that successful sexual function depends not only on intact vascular, hormonal, and neurologic systems but also on intact psychological and social responses. Several psychological factors may be manifested as problems of low desire, erectile failure, or premature ejaculation. A discussion of the psychological contribution to impotence is beyond the scope of this book.

Treatment

Management of erectile dysfunction requires an initial evaluation to differentiate organic causes from psychogenic causes. Further evaluation to distinguish among the various organic causes may then be needed. Once a psychogenic cause has been ruled out, several therapeutic options exist. Surgical options include the insertion of an inflatable or semirigid prosthetic device into the corpora cavernosa. In the past few years, several investigators have discovered that intracavernous injection of various vasoactive substances can cause an erection. Several of these substances, including papaverine, phentolamine, and prostaglandin E1, are commonly used and afford a nonsurgical treatment option.

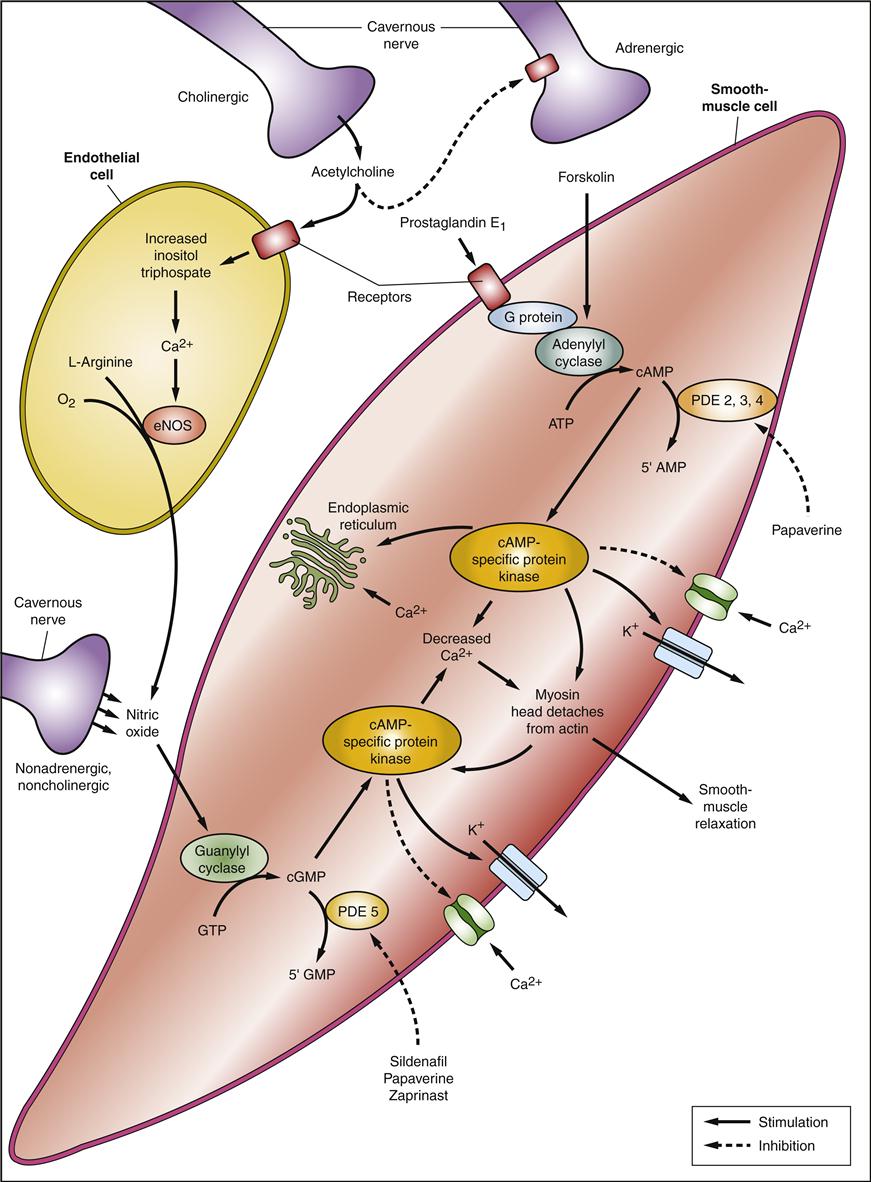

Viagra, the first oral therapy for erectile dysfunction, is the citrate salt of sildenafil, a selective inhibitor of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)–specific phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5). To understand its clinical pharmacology, a review of some of the physiologic mechanisms of erection follows. Briefly, erection of the penis involves release of nitric oxide in the corpus cavernosum during sexual stimulation. Nitric oxide then activates the enzyme guanylate cyclase, and the subsequently increased levels of cGMP produce smooth muscle relaxation in the corpus cavernosum and allow inflow of blood. Sildenafil has no direct relaxant effect on isolated human corpus cavernosum, but it enhances the effect of nitric oxide by inhibiting PDE5, which is responsible for degradation of cGMP in the corpus cavernosum. When sexual stimulation causes local release of nitric oxide, inhibition of PDE5 by sildenafil causes increased levels of cGMP in the corpus cavernosum, smooth muscle relaxation, and inflow of blood to the corpus cavernosum, which results in erection (Figure 31-5). Sildenafil citrate at the recommended doses appears to have no effect in the absence of sexual stimulation and affords another nonsurgical treatment option. Two newer agents for erectile dysfunction are Levitra and Cialis. In any particular patient, one of the three available oral medications may work better than the others. None of these agents should be used in conjunction with nitrate medications.

Smooth muscle relaxation in the corpus cavernosum is the underlying mechanism of erection. The principal neurotransmitter is NO acting through cGMP and G-protein. Pharmacologic agents that produce erection act through this pathway by regulation of the intracellular balance of Ca2+ and K+ concentrations. ATP, Adenosine triphosphate; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; GTP, guanosine triphosphate; NO, nitric oxide; eNOS, nitric oxide synthase; PDE5, phosphodiesterase type 5. (Redrawn from Lue TF: Erectile dysfunction, New Engl J Med 342:1802-1813, 2000.)

Another nonsurgical alternative entails the use of a vacuum device to sustain an erection. Finally, in very specific cases of erectile dysfunction, surgical procedures may be done to revascularize the arterial supply of the penis or ligate the penile venous drainage.

Premature Ejaculation

Premature ejaculation (PE) is the most common male sexual dysfunction and is present in up to 30% of all males. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines PE as “persistent or recurrent ejaculation with minimal stimulation before, on, or shortly after penetration and before the person wishes it, over which the sufferer has little or no voluntary control, which causes the sufferer and/or partner bother or distress.”23

Etiology and treatment

The etiology of PE is not well-defined but can be both biological and psychosocial. The diagnosis is achieved with a careful medical and sexual history and physical examination.

There are no FDA-approved medications for treatment but several are currently being used off label (Table 31-1). Further research will elucidate the causes and allow for better treatment in the future.

TABLE 31-1

MEDICAL THERAPY OPTIONS FOR THE TREATMENT OF PREMATURE EJACULATION∗

| ORAL THERAPIES | TRADE NAMES† | RECOMMENDED DOSE‡§ |

| Nonselective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors | ||

| Clomipramine | Anafranil | Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|