Alterations in Female Genital and Reproductive Function

Rosemary A. Jadack

Key Questions

• What are the differentiating factors of the common menstrual disorders?

• How can the pain of endometriosis be differentiated from that of dysmenorrhea?

• What is the rationale for routine Papanicolaou testing for cervical cancer?

• What factors contribute to the high mortality rate of ovarian cancer?

• How can benign and malignant breast lumps be clinically differentiated?

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Copstead/

The complex functioning of the female reproductive system described in Chapter 32 may be subject to alterations in structure and function throughout a woman’s life that can have far-reaching effects on her health and well-being. This chapter is a survey of these alterations and describes the pathophysiologic basis of the most common disorders of the female reproductive system. In addition, current therapeutics for these alterations, including pharmacologic therapy, will be summarized. The information presented here is an introduction to these complex areas, and the reader may wish to consult in-depth gynecology and obstetrics texts for more detailed information.

Perhaps no other function of the human body is so closely linked to psychological, social, and spiritual concerns as reproductive function. Any alteration in reproductive status (or the perceived threat of such an alteration) may have profound effects on an individual. Clinicians caring for women experiencing alterations in functioning of the reproductive system should bear in mind the profundity of such alterations for the individual woman and must also maintain an awareness of the context in which women seek help for such problems. A clinical approach in which information is freely shared between caregiver and client and in which mutual decision making is an integral part of the therapeutic environment is a necessary component of care for women seeking help for reproductive concerns. Previous clinical approaches in which women’s concerns were labeled as unimportant or merely psychogenic often resulted in anger, frustration with health care providers, and withdrawal from the health care delivery system. Women consumers of health care are now seeking active involvement in their own care, and clinicians who care for women experiencing the alterations described in this chapter need to approach women’s health concerns with sensitivity and openness.

Menstrual Disorders

Alterations in the normal functioning of the menstrual cycle include amenorrhea (no menses), abnormal uterine bleeding patterns, and dysmenorrhea (painful menstruation). Although many pathologic conditions can cause these alterations, an obvious cause is often not found.

Amenorrhea

Etiology and pathogenesis

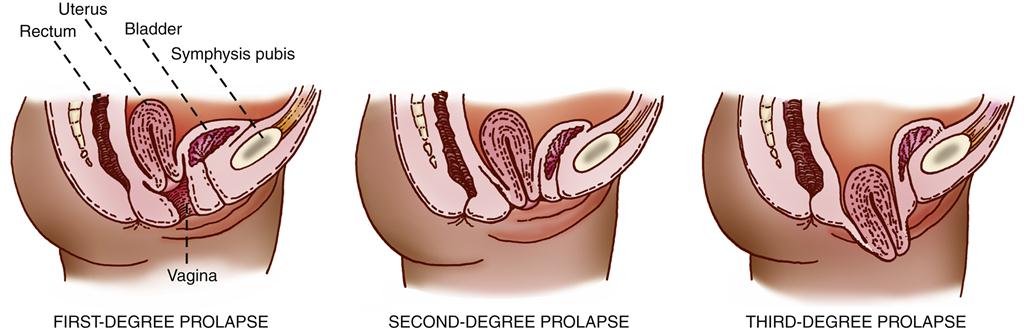

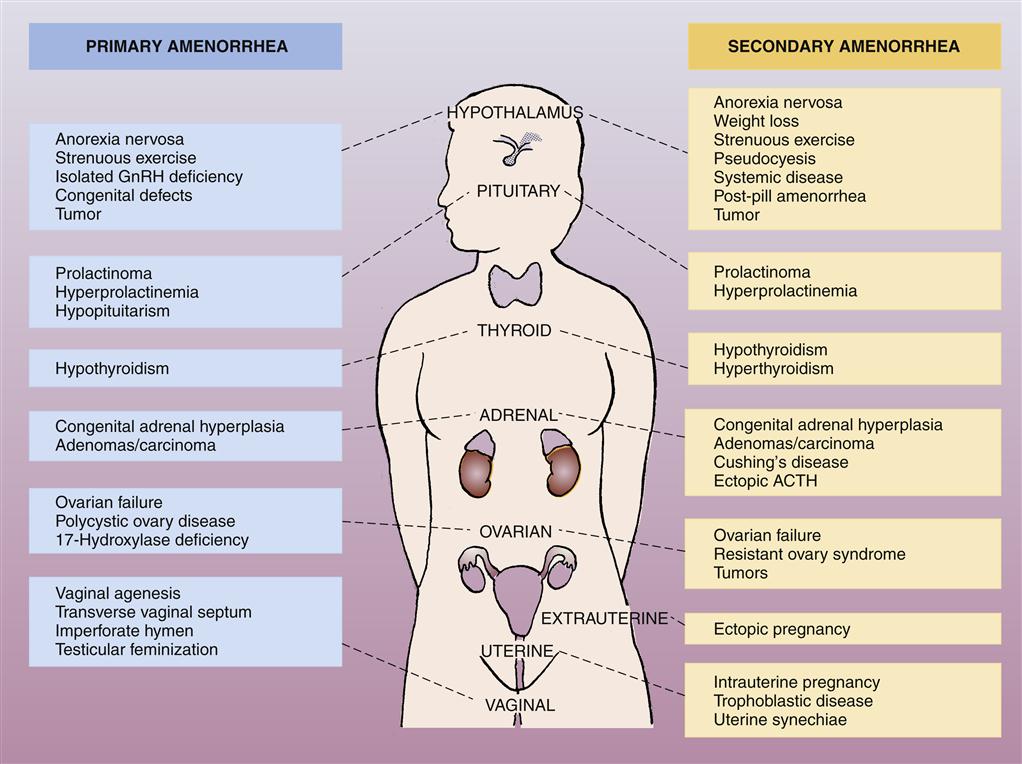

Amenorrhea is the absence or suppression of menstruation in a female age 16 years or older; it occurs if a woman misses three or more consecutive periods. Amenorrhea is categorized as either primary or secondary. Primary amenorrhea is the failure to begin menses by the age of 16 years. Secondary amenorrhea is the cessation of established, regular menstruation for 6 months or longer. Figure 33-1 shows causes of primary and secondary amenorrhea.

ACTH, Adrenocorticotropic hormone; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone. (From Black JM, Hawks JH: Medical-surgical nursing: clinical management for positive outcomes, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2009, Saunders, p 915.)

Amenorrhea is normal before menarche (the first menstrual period at the time of puberty), after menopause, and during pregnancy and lactation.1 At other times, it is considered pathologic and may result from a wide range of pathophysiologic causes (see Figure 33-1). In the majority of cases, amenorrhea is due to an abnormal pattern of hormonal functioning that interrupts the normal sequence of events in which the endometrial tissue lining the uterus proliferates and then is sloughed. The endometrial tissue must be stimulated and regulated by the correct quantity and sequence of the female sex hormones estrogen and progesterone and the gonadotropic hormones follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). As described in Chapter 32, the menstrual cycle is dependent on the sequential changes in estrogen and progesterone levels. The initial rise in LH and FSH levels in the menstrual cycle occurs in response to a decline in estrogen and progesterone levels; estrogen levels then rise again in response to actions of the gonadotropic hormones, and the endometrium proliferates again in response to estrogen secretion. Thus events that prevent estrogen production, interfere with the normal fluctuations in estrogen levels, or block the action of estrogen on the endometrium will result in abnormal or absent menstrual flow.2,3 Such events may include physical or emotional stress, which can interfere with normal production of the gonadotropic hormones and alter the pattern of estrogen functioning. In addition, ovarian, adrenal, or pituitary tumors may interfere with the normal production of female sex hormones or LH and FSH. Neoplasms of the ovaries or adrenal and pituitary glands may result in excess or deficient production of these hormones, with a consequent interruption in normal menstrual flow.

Treatment

Therapeutic strategies for amenorrhea are directed to correcting the cause of the interruption in hormonal functioning and may include the use of hormonal supplementation to reinstate a normal sequence of events in the menstrual cycle. If amenorrhea is the result of a neoplastic process, surgery may be indicated for tumor removal.

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Patterns

Irregular or excessive bleeding from the uterus is one of the most common alterations in the female reproductive system. Uterine bleeding that varies from a woman’s normal pattern either in quantity or in frequency may occur at any age and for a variety of reasons.

Etiology, clinical manifestations, and treatment

The most common alterations in uterine bleeding patterns and their causes are described here. Metrorrhagia, or bleeding between menstrual periods, usually results from slight physiologic bleeding from the endometrium during ovulation but may also result from other causes such as uterine malignancy, cervical erosions, and endometrial polyps or as a side effect of estrogen therapy.1 Hypomenorrhea, or a deficient amount of menstrual flow, results from endocrine or systemic disorders that may interfere with proper functioning of the hormones in the menstrual cycle, or it may be due to partial obstruction of menstrual flow by the hymen or a narrowing of the cervical os. Oligomenorrhea, or infrequent menstruation, usually reflects failure to ovulate because of an endocrine or systemic disorder with accompanying inappropriate hormonal function. Similarly, polymenorrhea, an increased frequency of menstruation, may be associated with ovulation and may be caused by endocrine or systemic factors. Menorrhagia, an often debilitating increase in the amount or duration of menstrual bleeding, usually results from lesions of the female reproductive organs such as uterine leiomyomas, endometrial polyps, and adenomyosis. It is often managed with surgery, oral contraceptives, and/or antiprostaglandins. More recently, a progestin-containing intrauterine device has shown promise in reducing menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, and anemia.4,5

The term dysfunctional uterine bleeding is used to describe abnormal endometrial bleeding not associated with tumor, inflammation, pregnancy, trauma, or hormonal effects. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is most common around the time of menarche and menopause and not as common in women before menopause.6 In adolescents, dysfunctional uterine bleeding is most often due to immaturity in functioning of the pituitary and ovary, which have not yet properly orchestrated their activities.7 Thus an imbalance may be present in the ratio of estrogen to progesterone. Absent or diminished levels of progesterone will result in a thick and extremely vascular endometrium that lacks structural support. As a result of this fragile structure, spontaneous and superficial hemorrhage occurs randomly throughout the endometrium. In addition, the blood vessels in the endometrium fail to constrict to limit the extent and duration of bleeding.7 Uterine bleeding that is abnormal in both quantity and frequency can therefore occur in a noncyclic pattern.

In perimenopausal women, dysfunctional uterine bleeding may be the result of progressive degeneration and failure of the ovary to produce estrogen. As the number of ovarian follicles diminishes, the production of estrogen by the ovary becomes unpredictable, and the secretion of LH and FSH may also assume an unpredictable pattern. As in adolescents with dysfunctional uterine bleeding, diminished or absent production of progesterone may result in unopposed stimulation of the endometrium by estrogen, with subsequent unpredictable bleeding from a fragile endometrium.6,7

Dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea is menstruation that is painful enough to limit normal activity or to cause a woman to seek health care. Dysmenorrhea is a widespread phenomenon that affects many women across the reproductive years, including girls of high school age through perimenopausal women. Although symptoms of dysmenorrhea tend to decrease with age, the traditional notion that childbirth permanently decreases symptoms is unfounded. In addition, the contention that women with dysmenorrhea tend to be neurotic has been refuted in well-designed psychiatric research studies.7 Recent research into the physiologic process of uterine contractions has enhanced our understanding of the causes of dysmenorrhea and has thus resulted in better treatment.

Etiology and clinical manifestations

Dysmenorrhea is usually classified as primary (not related to any identifiable pathologic condition) or secondary (related to an underlying pathologic condition). The cramps that occur with primary dysmenorrhea are usually located in the suprapubic region and are sharp in quality. The pain may radiate to the inner aspect of the thighs and lower sacral area and may be accompanied by nausea, diarrhea, and headache.2 Primary dysmenorrhea usually develops 1 or 2 years after menarche, when ovulatory cycles are established. Under the influence of progesterone, increased amounts of prostaglandins, potent hormone-like unsaturated fatty acids, are released from the endometrium. Prostaglandins have significant effects on smooth muscle and vasomotor tone; when released from the endometrium, prostaglandins promote uterine contractions and ischemia of the endometrial capillaries and thereby cause the cramping pain of dysmenorrhea.8,9

Secondary dysmenorrhea is characterized more often by dull pain that may increase with age. It is associated with pelvic disorders such as endometriosis, leiomyomas, or pelvic adhesions.8,9

Treatment

Recent therapeutic strategies for the management of primary dysmenorrhea have focused on the phenomenon of prostaglandin-induced enhanced uterine contractility. The use of prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors such as ibuprofen and naproxen, which inhibit the formation of prostaglandins, has been very effective in many women experiencing dysmenorrhea.10 Other approaches that use steroid hormones, such as progestins or combined high-progestin/low-estrogen oral contraceptives, have also been advocated. The rationale is that production of the high menstrual levels of prostaglandins needed to produce dysmenorrhea requires high levels of estrogen without progesterone in the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle. Progestin administration therefore inhibits the production of prostaglandins and relieves the symptoms of dysmenorrhea.7 However, the use of steroid hormones may involve significant risks, which the individual client must weigh against the benefits of such therapy.

Therapeutic strategies for secondary dysmenorrhea may involve diagnostic operative procedures such as laparoscopy, as well as medical and surgical therapy for the underlying condition.9

Alterations in Uterine Position and Pelvic Support

Alterations in uterine position and pelvic support may occur anytime during a woman’s reproductive years. The major support for the uterus and upper part of the vagina is provided by the thickenings of the endopelvic fascia known as the cardinal ligaments. Although tearing of the cardinal ligaments during labor and delivery is rare, they can be stretched abnormally during a difficult or prolonged delivery and subsequently fail to support the pelvic organs adequately.7 In addition, congenital defects in the muscles of the pelvic floor may promote alterations in position of the uterus and other pelvic structures. The two most common alterations in uterine position are uterine prolapse and retrodisplacement of the uterus. Other commonly occurring alterations resulting from a weakening of the vaginal and pelvic floor musculature are cystocele and rectocele.

Uterine Prolapse

Etiology

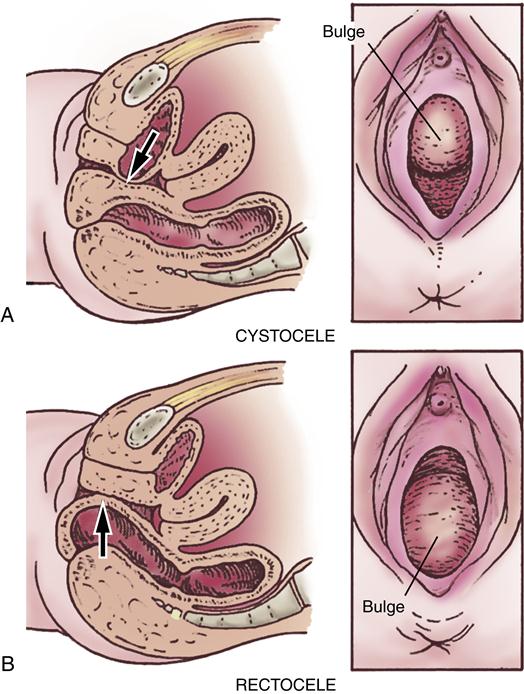

The axis of the uterus normally forms an acute angle with the axis of the vagina. This anatomic feature itself tends to prevent a prolapse, or sinking, of the uterus from its normal position. Descent of the uterus occurs when supporting structures, such as the uterosacral ligaments and the cardinal ligaments, relax and allow the relationship of the uterus to the vaginal axis to be altered. This relaxation permits the cervix to sag downward into the vagina. If the support of the vaginal wall is also compromised, the pressure of the abdominal organs on the uterus will gradually force it downward through the vagina into the introitus.11 Uterine prolapse may occur at any age. In female infants and in women who have never given birth, congenital defects in the basic integrity of the pelvic supporting structures are usually responsible. Trauma to the ligaments during childbirth is the cause of uterine prolapse in women who have given birth, particularly if multiple deliveries have occurred. Uterine prolapse is classified as first-degree, second-degree, or third-degree according to the level to which the uterus has descended (Figure 33-2). In first-degree prolapse, the uterus is approximately halfway between the vaginal introitus and the level of the ischial spines. In second-degree prolapse, the end of the cervix has begun to protrude through the introitus. In third-degree or complete prolapse, the body of the uterus is outside the vaginal introitus. Figure 33-3 shows a third-degree, or complete, uterine prolapse.

Clinical manifestations

The symptoms of uterine prolapse depend on the degree of severity of prolapse. The woman may become increasingly aware of a sensation of bearing down and discomfort in the vagina. If the prolapse has advanced to the second or third degree, she may note discomfort while walking or sitting and have difficulty urinating. In addition, as the end of the cervix begins to protrude outside the body, it may be subject to trauma from friction and ulceration. Bleeding and ulceration of the cervix may be present.

Treatment

Uterine prolapse is one of the most common reasons for hysterectomy, usually from the vaginal approach.12 In patients who are at poor risk for surgery or who choose not to have a hysterectomy, a pessary, which is a small supportive device, is inserted to hold the uterus in place.11

Retrodisplacement of the Uterus

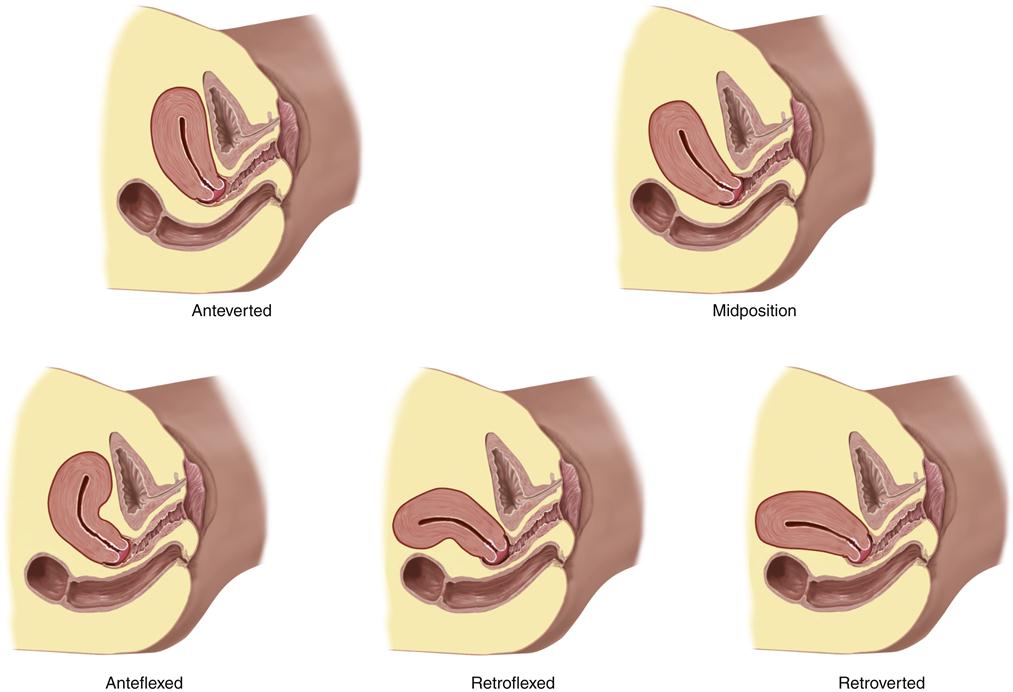

The term retrodisplacement refers to situations in which the body of the uterus is displaced from its usual location overlying the bladder to a position in the posterior of the pelvis.13 As shown in Figure 33-4, the uterus may be in one of five positions: anteverted, midposition, anteflexed, retroflexed, or retroverted.

Note that the classifications describe the position of the long axis of the uterus with respect to the long axis of the body. (From Jarvis C: Physical examination and health assessment, ed 6, St Louis, 2012, Elsevier, p 745.)

Etiology and clinical manifestations

Retrodisplacement can be detected in 20% to 30% of all women.14 It may be a normal variation and therefore be present throughout a woman’s entire life, or it may develop after childbirth when the supporting structures are injured.

In many women, no symptoms occur from uterine retrodisplacement. In some women, symptoms of pelvic pain or pressure, dysmenorrhea, and dyspareunia (painful intercourse) may be present. In addition, infertility has been associated with retrodisplacement.7

Treatment

If the woman has no symptoms, no treatment is indicated. The use of a pessary to support the uterus in a normal position may relieve the symptoms, but surgical correction is sometimes indicated when symptoms are severe.7 If surgery is indicated, less invasive, laparoscopic surgical procedures are often preferred.13,14

Cystocele

Etiology

A cystocele is a protrusion of a portion of the urinary bladder into the anterior of the vagina at a weakened part of the vaginal musculature (Figure 33-5, A). The defect in the vaginal wall is usually caused by injury during childbirth or surgery but may also result from the aging process or develop as an inherent weakness. Other predisposing factors include obesity and a history of lifting heavy objects. The pressure created by this protrusion causes the anterior vaginal wall to bulge in a downward direction.

Clinical manifestations and treatment

A wide range of symptoms may be present, depending on the degree of severity of the cystocele. A mild degree of protrusion of the bladder may result in no symptoms. In moderate to severe cases, a sensation of pressure can be felt in the vagina, along with dysuria, incontinence, and back pain. Fullness at the vaginal opening may be observed, as may a soft, reducible mucosal mass bulging into the anterior of the vaginal introitus.

Surgical repair of the vagina is done to correct the cystocele and reestablish support of the anterior vaginal wall. The bladder is restored to a normal position by reinforcement of the weakened portion of the anterior vaginal wall. Prosthetic mesh may also be inserted to further support the bladder during the repair of the cystocele.

Rectocele

Etiology

A rectocele (also called proctocele) is a protrusion of the anterior rectal wall into the posterior of the vagina at a weakened part of the vaginal musculature (see Figure 33-5, B). As for a cystocele, the defect in the vaginal wall is usually caused by injury during childbirth or surgery but may also occur with aging or arise as an inherent weakness. Other predisposing factors for a rectocele include multiparity, obesity, and postmenopausal status. The rectocele forms a bulging mass beneath the posterior vaginal mucosa and pushes downward into the lower vaginal canal. Gradually, the rectum may be torn from its fascial and muscular attachments to the pelvic wall. The levator ani muscles may also become stretched or torn.

Clinical manifestations and treatment

A wide range of symptoms may be present, depending on the degree of severity of the rectocele. The patient may report a history of difficulty in bowel evacuation and may have experienced chronic constipation with laxative and enema dependency. A feeling of pressure may also be reported, along with painful sexual intercourse. Physical examination reveals a mass bulging into the posterior of the vaginal introitus.5

Surgical repair of the vagina is done to correct the rectocele and reestablish support of the posterior vaginal wall. The rectum is restored to its normal location, and the levator ani muscles are realigned in proper position.

Inflammation and Infection of the Female Reproductive Tract

Inflammatory and infectious processes of the female reproductive tract may have effects that range from discomfort to life-threatening situations. Because the infectious agents responsible for inflammation and infection of the female genital tract may be sexually transmitted, some overlap in the discussion of these processes and sexually transmitted diseases is necessary. This chapter will describe the two principal inflammatory and infectious processes of the upper and lower female reproductive tract: pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and vulvovaginitis. The reader may wish to refer to Chapter 34 for additional information on sexually transmitted infections.

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

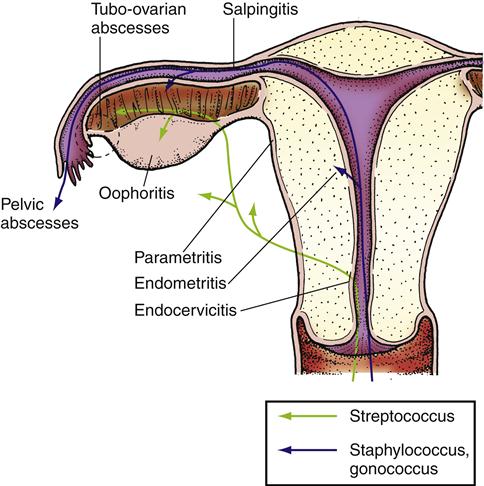

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is any acute, subacute, recurrent, or chronic infection of the oviducts and ovaries with involvement of the adjacent reproductive organs (Figure 33-6). It includes inflammation of the cervix (cervicitis), uterus (endometritis), oviducts (salpingitis), and ovaries (oophoritis). When the connective tissue underlying these structures between the broad ligaments is also involved, the condition is called parametritis.1

Hospitalizations for PID have declined between 2001 and 2009.15,16 The CDC reports approximately 113,000 initial physician visits for PID in 2010.15,16 Significant reproductive health problems may occur as a result of PID. A substantial number of women with a history of PID eventually experience one or more long-term health problems. Infertility is present in 10% to 15% of women who have experienced PID, and the incidence of ectopic pregnancy is increased six to ten times.17 Chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, pelvic adhesions, and chronic inflammation and abscesses of the oviducts and ovaries may all occur in women after PID.7

Etiology

Normally, cervical secretions provide protective and defensive functions for the reproductive organs. By providing a bacteriostatic barrier, cervical mucus prevents bacterial agents present in the cervix or vagina from ascending into the uterus. Therefore, conditions or surgical procedures that alter or destroy cervical mucus may impair this bacteriostatic mechanism. PID may follow the insertion of an intrauterine device, pelvic surgery, abortion procedures, and infection during or after pregnancy. Bacteria may also enter the uterine cavity through the bloodstream or from drainage from other foci of infection such as a pelvic abscess, ruptured appendix, or diverticulitis of the sigmoid colon.1

PID can result from infection with aerobic and anaerobic organisms. Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis are the most common causative agents because they readily penetrate the bacteriostatic barrier of cervical mucus. However, a variety of bacterial organisms may contribute to the development of PID, including staphylococci, streptococci, diphtheroids, and coliforms such as Pseudomonas and Escherichia coli. These bacteria are commonly found in cervical mucus, and PID can result from infection by one or several of these bacteria. In addition, PID may occur after multiplication of bacteria in the endometrium that are normally nonpathogenic. During parturition, the traumatized endometrium favors the multiplication of bacteria.1

Clinical manifestations

The associated signs and symptoms of PID vary with the affected part of the reproductive tract but generally include abdominal tenderness and tenderness or pain of the cervix or adnexa on palpation. In addition, the temperature may be elevated higher than 38° C and the white blood cell count elevated greater than 10,000/mm3. A pelvic abscess or inflammatory mass may be present on physical examination or ultrasound, and purulent vaginal discharge may be noted.1,7

Treatment

Early and aggressive use of antibiotic agents best suited for the causative organisms is essential in preventing the progression of PID. Various antibiotic regimens involving the use of multiple antimicrobial agents have been suggested by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for use in PID.18 Inpatient hospitalization may be indicated for patients with rapidly progressing PID and for those requiring surgical drainage of pelvic abscesses. Rupture of a pelvic abscess is a potentially life-threatening condition, and a total abdominal hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of both oviducts and ovaries) may be indicated in this situation.

Vulvovaginitis

Vulvovaginitis is an inflammation of the vulva (vulvitis) and vagina (vaginitis). Because the vulva and vagina are anatomically close to each other, inflammation of one location usually precipitates inflammation of the other. Vulvovaginitis may occur at any time during a girl’s or woman’s life and affects most females at some point in life.1

Etiology

Infection by Candida albicans (formerly called Monilia) accounts for approximately half of all reported cases of vulvovaginitis. (Infection by Candida is referred to as candidiasis.18) C. albicans is a fungus that requires glucose for growth; thus its growth may be promoted during the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle when glycogen levels increase in the vaginal environment. In addition, other conditions in which the glycogen content of the vagina is enhanced may favor candidiasis, such as diabetes, pregnancy, and the use of oral contraceptives. Other factors predisposing to the development of vulvovaginitis from Candida infection include the use of estrogen supplementation and antibiotics. Women using estrogen supplementation in the perimenopausal period may be at greater risk for candidal infection of the vagina inasmuch as the glycogen content of the vagina may increase with these therapies. The mechanism by which antibiotic use promotes candidiasis is presently unclear, but it is thought that destruction of the bacteria that normally exert the protective effect of consuming Candida results in overgrowth of the Candida population with subsequent infection.1,7

Other infectious agents that may result in vulvovaginitis include Trichomonas vaginalis, Haemophilus vaginalis, and N. gonorrhoeae. Viral agents that may cause vulvovaginitis include human papillomavirus (venereal warts, condylomata acuminata) or herpesvirus type 2. These organisms can be transmitted during sexual intercourse and are discussed in detail in Chapter 34.

In addition to infectious processes, vulvovaginitis may be promoted by conditions or agents that irritate the vulva and vagina. Chemical irritation or allergic reactions to detergents, feminine hygiene products, and toilet paper may be a causative factor. Trauma to the vulva or vagina or the atrophy of the vaginal wall that occurs postmenopausally may predispose to vulvovaginitis as well.1

Clinical manifestations

Vulvovaginitis from candidiasis results in a thick, white discharge and red, edematous mucous membranes with white flecks adhering to the vaginal wall. Intense itching (pruritus) usually accompanies this discharge. The vaginal pH is usually normal (less than 4.5), and fungal organisms are often seen on microscopic studies. Vulvovaginitis from other infectious agents may involve a malodorous, purulent discharge. Irritation and subsequent inflammation of the vulva and vagina may be manifested by red, swollen labia, pain on urination and intercourse, and itching.

Treatment

Appropriate medical therapy for the causative organisms is usually instituted, including local antifungal preparations for vaginal candidiasis and local and systemic antibiotic therapy for vulvovaginitis caused by bacterial agents. Cool compresses and sitz baths provide relief of itching and burning of inflamed tissues. Avoidance of factors that promote irritation of the vulva, such as drying soaps, nonabsorptive underwear, and tight clothing, is also of therapeutic benefit.1

Bartholinitis

Bartholinitis is an inflammation of the Bartholin glands, which are located on either side of the vaginal orifice and lubricate the vaginal introitus with a clear, viscous secretion. The location of Bartholin glands renders them susceptible to access by bacteria such as N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, and other organisms.

Clinical manifestations and treatment

Once bacteria are established, an abscess (also referred to as a Bartholin cyst) may form and cause tenderness and swelling at the site. Pus may be observed exuding from the duct orifice leading to the affected gland, and symptoms of fever and malaise are present in some individuals. Laboratory culture with proper diagnosis of the causative organism is performed, and appropriate antibiotic therapy is usually instituted. Surgical incision and drainage of the abscess may be necessary for effective management.