Figure 2.1 In following the “five + 1 rights” of medication administration, you always verify that the “right patient” is receiving the medication by using two identifiers, one of which is checking the patient’s identification bracelet.

Right Drug

Drug names can be confused, especially when the names sound similar or the spellings are similar. Hurriedly preparing a drug for administration or failing to look up questionable drugs can put you at increased risk for administering the wrong drug. Appendix B identifies examples of drugs that can easily be confused. An error in drug name or amount can be found when you compare the medication administration record (MAR): (1) with the container label, (2) as the item is removed from the cart, and (3) before the actual administration of the drug (Fig. 2.2).

Figure 2.2 Before administering the medication, compare the medication, the container label, and the medication record to ensure that the patient receives the “right drug” and the “right dose.”

Right Dose, Right Route, and Right Time

Written orders are obtained from a primary health care provider for the administration of all drugs. The primary health care provider’s order must include the patient’s name, the drug name, the dosage form and route, the dosage to be administered, and the frequency of administration. The primary health care provider’s signature must follow the drug order. In an emergency, you may administer a drug with a verbal order from the primary health care provider. However, the primary health care provider must write and sign the order as soon as the emergency is over.

If a verbal order is given over the telephone, write down the order, repeat back the information exactly as written, and then ask for a verbal confirmation that it is correct. Any order that is unclear should be questioned, particularly unclear directions for the administration of the drug, illegible handwriting on the primary health care provider’s order sheet, or a drug dose that is higher or lower than the dosages given in approved references.

Right Documentation

After the administration of any drug, record the process immediately (Fig. 2.3). Immediate documentation is particularly important when drugs are given on an as-needed (PRN) basis. For example, most analgesics require 20 to 30 minutes before the drug begins to relieve pain. A patient may forget that he or she received a drug for pain, may not understand that the administered drug was for pain, or may not know that pain relief is not immediate, and may ask another nurse for the drug again. If the administration of the analgesic was not recorded, the patient might receive a second dose of the analgesic shortly after the first dose. This kind of situation can be extremely serious, especially when opioids or other central nervous system depressants are administered. Immediate documentation prevents accidental administration of a drug by another individual. Proper documentation is essential to the process of administering drugs correctly.

Figure 2.3 Always document the medication immediately after the drug is administered.

General Principles of Drug Administration

Considerations in Drug Administration

You must have factual knowledge of each drug, the reasons for use of the drug, the drug’s general action, the more common adverse reactions associated with the drug, special precautions in administration (if any), and the normal dose ranges before you administer the drug to a patient.

When drugs are given frequently, you will become familiar with their pharmacologic information. Yet, when drugs are given less frequently or when a new drug is introduced, you should obtain information from reliable sources, such as the drug package insert, Internet sources, or the hospital department of pharmacy. It is important to check current and approved references for all drug information.

Take patient considerations, such as allergy history, previous adverse reactions, patient comments, and change in patient condition, into account before administering the drug. Before giving any drug for the first time, ask the patient about any known allergies and any family history of allergies. This includes allergies not only to drugs but also to food, pollen, animals, and so on. Patients with a personal or family history of allergies are more likely to experience additional allergies and must be monitored closely.

If the patient makes any statement about the drug or if there is any change in the patient, these situations are carefully considered before the drug is given. Examples of situations that require consideration before a drug is given include:

• Problems that may be associated with the drug, such as nausea, dizziness, ringing in the ears, and difficulty walking. Any comments made by the patient may indicate the occurrence of an adverse reaction. Withhold the drug until references are consulted and the primary caregiver contacted. The decision to withhold the drug must have a sound rationale and be based on knowledge of pharmacology.

• Patient or family comments stating that the drug looks different from the one previously received, that the drug was just given by another nurse, or that the patient thought the primary health care provider discontinued the drug therapy.

• A change in the patient’s condition, a change in one or more vital signs, or the appearance of new symptoms. Depending on the drug being administered and the patient’s diagnosis, these changes may indicate that the drug should be withheld and the primary health care provider contacted.

The Medication Order

Before a medication can be administered in a hospital or other agency, you must have a physician’s order. Medications are ordered by the primary health care provider, such as a physician, dentist, or, in some cases, an advanced nurse practitioner. Common orders include the standing order, the single order, the PRN order, and the STAT (to be done immediately) order. See Display 2.1 for an explanation of each.

Display 2.1 Types of Medication Orders

Standing Order: This type of order is pre-established and approved for use by nurses and other health care providers under specific conditions in the absence of a health care provider. They may be drug orders for presurgical/procedure or postsurgical/procedure nursing care. Example: Cefotetan 1 gram IV 30 minutes preoperatively

Single order: An order to administer the drug one time only. Example: Valium 10 mg IM at 10:00 a.m.

PRN order: An order to administer the drug as needed. Example: Percocet 1–2 tablets orally q 4 hr PRN for pain

STAT order: A one-time order given as soon as possible. Example: Morphine 10 mg IV STAT for cardiac pain

Preparing a Drug for Administration

When preparing a drug for administration, observe the following guidelines:

• Always check the health care provider’s written orders and verify any questions with the primary health care provider before preparing the medication.

• Be alert for drugs with similar names. Some drugs have names that sound alike but are very different (see Appendix B). To give one drug when another is ordered could have serious consequences.

• Perform hand hygiene immediately before preparing a drug for administration. Do not let your hands touch medication, especially topical preparations that you may absorb through the tissue of the hands.

• Always check and compare the label of the drug with the MAR three times: (1) when the drug is taken from its storage area, (2) immediately before removing the drug from the container, and (3) before administering the drug to the patient.

• Never remove a drug from an unlabeled container or from a package whose label is illegible. Do not remove the wrappings of the unit dose until the drug reaches the bedside of the patient who is to receive it. After administering the drug, document immediately on the MAR drug record.

• Never crush tablets or open capsules without first checking with the clinical pharmacist. Some tablets can be crushed or capsules can be opened and the contents added to water or a tube feeding when the patient cannot swallow a whole tablet or capsule. Some tablets have a special coating that delays the absorption of the drug. Crushing the tablet may destroy the drug’s properties and result in problems such as improper absorption of the drug or gastric irritation. Capsules are gelatin and dissolve on contact with a liquid. The contents of some capsules do not mix well with water and therefore are best left in the capsule. If the patient cannot take an oral tablet or capsule, consult the primary health care provider because the drug may be available in liquid form.

• Never give a drug that someone else has prepared. The individual preparing the drug must administer the drug.

• Place drugs requiring special storage in the storage area immediately after they are prepared for administration. This rule applies mainly to drugs that need refrigeration, but may also apply to drugs that must be protected from exposure to light or heat.

Preventing Medication Errors

Medication errors include any event or activity that can cause a patient to receive the wrong dose, the wrong drug, an incorrect dosage of the drug, a drug by the wrong route, or a drug given at the incorrect time. Errors may occur in transcribing medication orders, when the drug is dispensed, or in administration of the drug. As a nurse and the medication administrator, you serve as the last defense against medication errors. When a medication error occurs, report it immediately so that any necessary steps to counteract the action of the drug or any observation can be made as soon as possible. In most institutions, if you made the error or discovered the error you must complete an unusual occurrence report and notify the primary care provider. It is important to report errors even when the patient suffers no harm.

Medication errors occur when one or more of the five + 1 rights have not been followed. Each time a drug is prepared and administered, the five + 1 rights must be a part of the procedure. In addition to consistently practicing the five + 1 rights, you should adhere to the following precautions to help prevent drug errors:

• Confirm any questionable orders.

• When calculations are necessary, verify them with another nurse.

• Listen to the patient when he or she questions a drug, the dosage, or the drug regimen.

• Never administer the drug until the patient’s questions have been adequately researched.

• Avoid distractions and concentrate on only one task at a time.

A significant number of errors can be made during administration of a drug. Errors most commonly occur because of a failure to administer a drug that has been ordered, administration of the wrong dose or strength of a drug, or administration of a drug at the wrong time. Two drugs often associated with errors are insulin and heparin.

Innovative nurses are using various methods to study and reduce medication errors in cost-effective ways. Workplace distractions are one of the biggest issues being addressed by these nurses. Bright vests, mats on the floor, and “Do Not Disturb” signs are used to help lessen the number of people who interrupt the nurse as medications are being prepared and given to patients. An example is illustrated in Figure 2.4.

A number of agencies have instituted policies and practices to help in the reporting and reduction of errors. These practices (termed Just Culture) focus on finding the system problem, not punishing the person who made the error. Therefore, it is even more important for you and other nurses to report errors and omissions so problems can be discovered and changed.

Figure 2.4 Reducing interruptions by wearing “Do Not Disturb” apparel is a cost-effective way to reduce drug errors.

National Patient Safety Goals

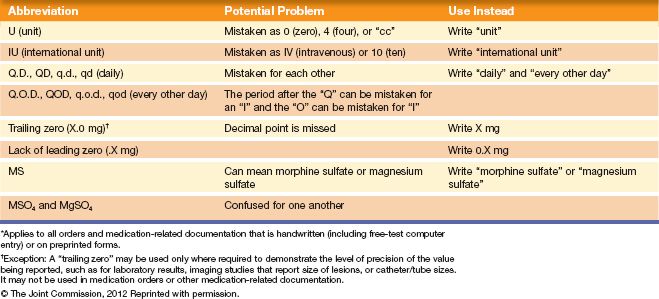

To evaluate the safety and quality of care provided by various accredited health care organizations, the Joint Commission establishes National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG) on a yearly basis. These goals are established to help accredited organizations address specific areas of concern with regard to patient safety. Several of these goals directly affect medication administration. For example, one of the first goals written that affects medication safety was the 2009 NPSG requiring improvement in the accuracy of patient identification. To meet this goal, institutions were required to use the two-identifier rule, where two methods must be used to identify the patient (other than the patient’s room number) when administering medication or blood products. Another important standard that institutions desiring accreditation must follow is to compile a list of abbreviations, symbols, and acronyms not to be used throughout the institution. The Joint Commission has developed its own list of abbreviations that may no longer be used in any written medical documents (e.g., care plans, medical orders, nurses’ notes). This list is referred to as the “minimum list.” See Table 2.1 for the official “Do Not Use” list. Facilities accredited by the Joint Commission are required to be in compliance with the National Patient Safety Standards. Current information on these standards can be found at the Joint Commission website (http://www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/npsgs.aspx).

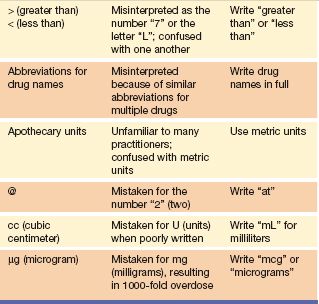

The list of error-prone abbreviations shown in Table 2.2 includes more abbreviations that are easily misinterpreted; therefore, providers are attempting to standardize terminology to reduce error.

Table 2.1 Joint Commission Official “Do Not Use” List*

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) is a nonprofit organization devoted to the study of medication errors and their prevention. In addition to offering safety and educational information, it contains a section called the Medication Errors Reporting Program. This program is designed to identify the number and type of drug errors occurring around the country. It is a program similar to the MedWatch program of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The goal of this voluntary reporting system is to collect data and disseminate information that will prevent such errors in the future. A link to the report form may be found online at http://www.ismp.org/. You are urged to participate in this important program as a means of protecting the public by identifying ways to make drug administration safer.

Table 2.2 Error-Prone Abbreviations

Drug Distribution Systems

Primary or specialty providers order drugs for administration. Pharmacists dispense the medications, and nurses carry out the actual administration. Several drug distribution systems are available to be used to carry out the process. A brief description of three methods follows.

Unit Dose System

The unit dose system is a method in which drug orders are filled and medications dispensed to fill each patient’s medication orders for a 24-hour period. The pharmacist dispenses each dose (unit) in a package that is typically labeled by the manufacturer and contains one tablet or capsule, a premeasured amount of a liquid drug, a prefilled syringe, or one suppository. Enough packaged drug for 1 day is placed in drawers in a special portable medication cart with a drawer for each patient. If the drug does not come individually packaged, a clinical pharmacist also may prepare unit doses. The pharmacy restocks the cart each day with the drugs needed for the next 24-hour period. If the cart is portable, you will take the drug cart to each patient’s room. Once every 24 hours, it goes back to the pharmacy to be refilled and for new drug orders to be placed.

Figure 2.5 Multiunit dose packs, frequently used for medication administration in long-term care settings.

In facilities where patients may stay for a long time, such as long-term care, the drug may be packaged using a multiunit dose method. With this system, individual doses are “bubble” packed onto a card that may hold up to 60 individual doses (Fig. 2.5). Cards are labeled for individual patients and may hold 1 to 2 months’ supply of a drug. These cards are then stored in slots for individual patients in a locked medication cart. When administering a drug, obtain the patient’s card and pop the individual dose out of the card, returning the card with its remaining doses to the medication cart.

Automated Medication Management System

Automated or computerized management systems (Fig. 2.6) are used in most hospitals or agencies distributing drugs. Drug orders are managed in the pharmacy from physician orders that are sent from the individual floors or units. Each floor or unit has a medication station in which medications are placed in specific drawers. Medications are individually packaged as in the unit dose system. The difference is that there is more drug in the tray if a number of patients are prescribed the same medication. Once the order is entered into the system, you may enter the patient’s name and the drug to be administered at the unit’s automated medication station. The drawer with the specific drug opens for you to remove the drug, and then using a computer touch screen, the dose is automatically recorded into the computerized system. Print out this information for individual patients as their MAR if the facility uses paper charting.

Figure 2.6 An automated medication system.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree