Two groups: Hermaphrodites and schistosomes

For both groups, snails release motile cercariae in water

Schistosoma cercariae in water infect humans through skin

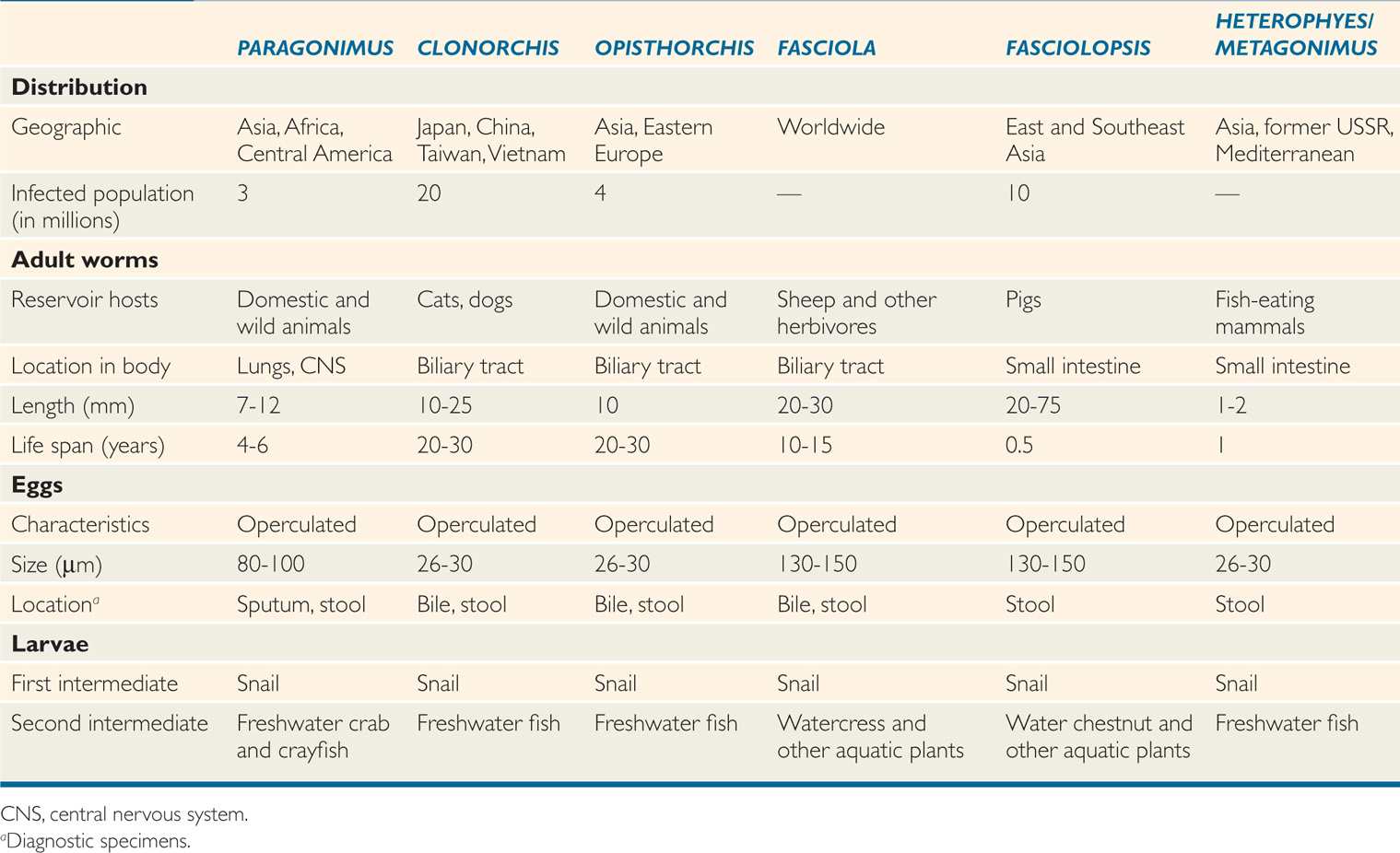

Of the many trematodes that infect humans, only the five of greatest medical importance are discussed here: The blood flukes, all of which are members of the genus Schistosoma (S mansoni, S haematobium, and S japonicum); and the lung (Paragonimus spp.) and liver (Clonorchis sinensis) flukes, which are hermaphroditic. Basic details of these and other hermaphroditic tissue and intestinal flukes are listed in Table 57–2.

TABLE 57–2 Hermaphroditic Trematodes

Hermaphroditic cercariae encyst on aquatic plant or animal before transforming into infectious metacercariae

PARAGONIMUS

![]() PARAGONIMUS SPECIES: PARASITOLOGY AND LIFE CYCLE

PARAGONIMUS SPECIES: PARASITOLOGY AND LIFE CYCLE

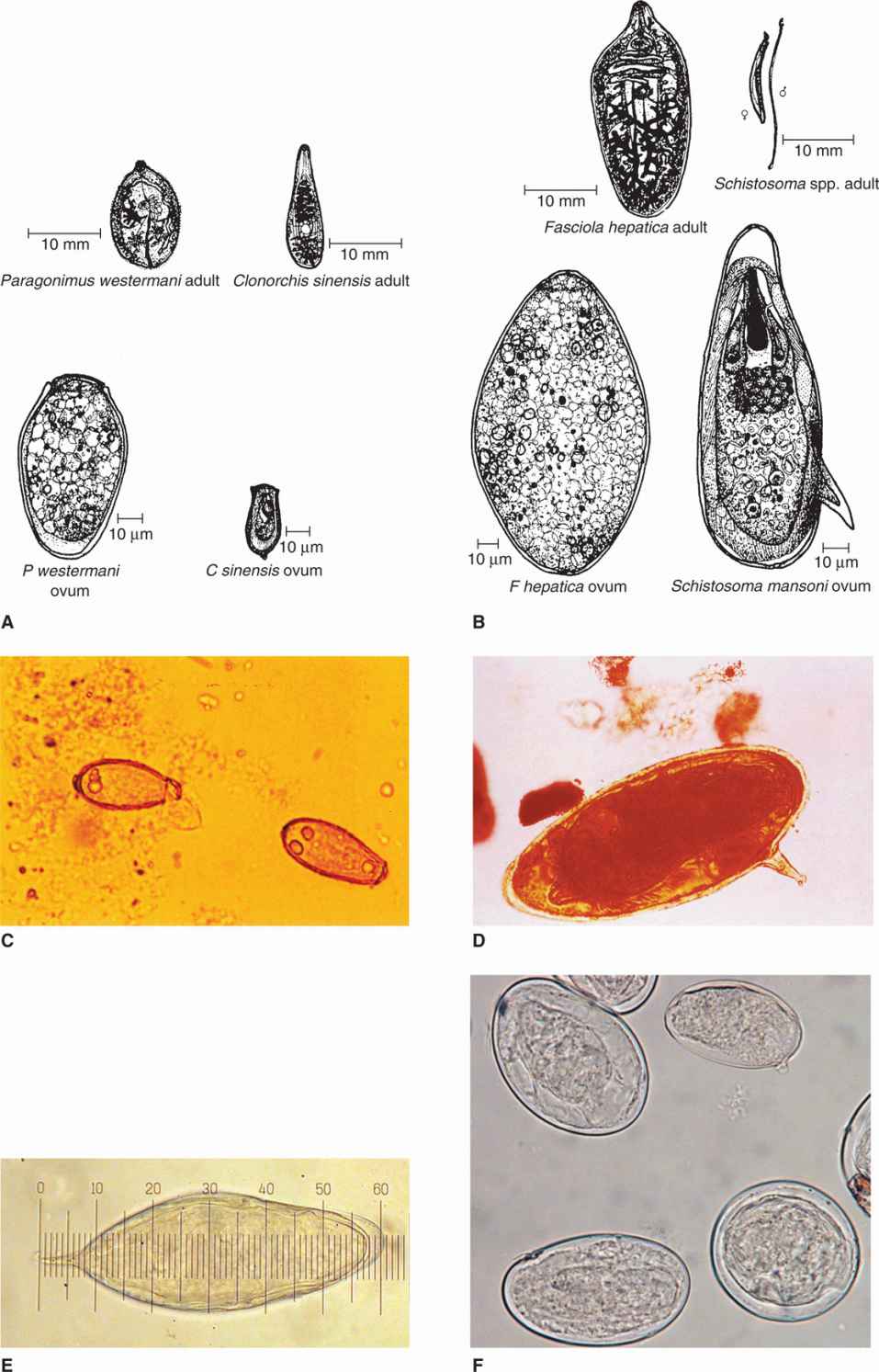

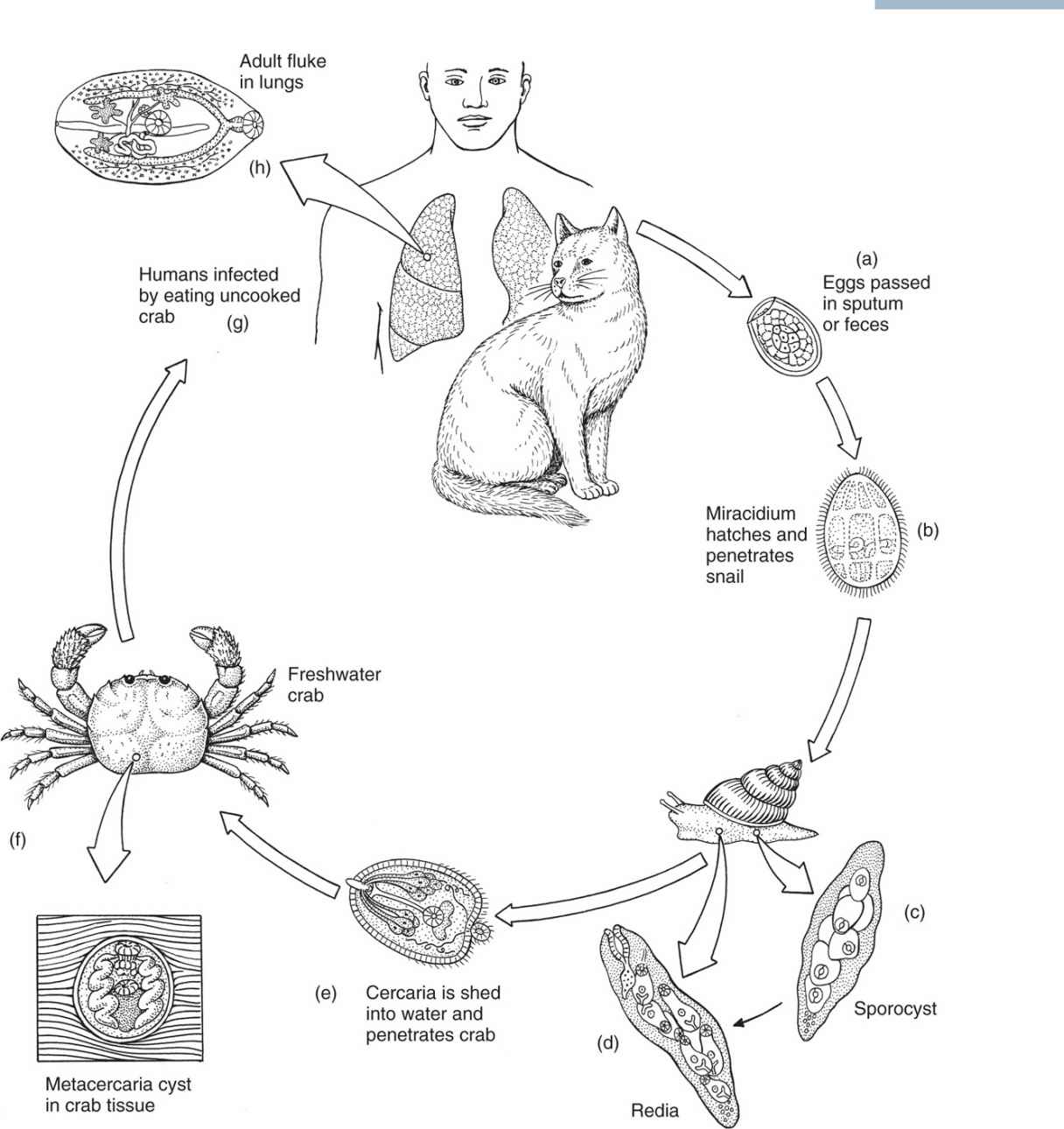

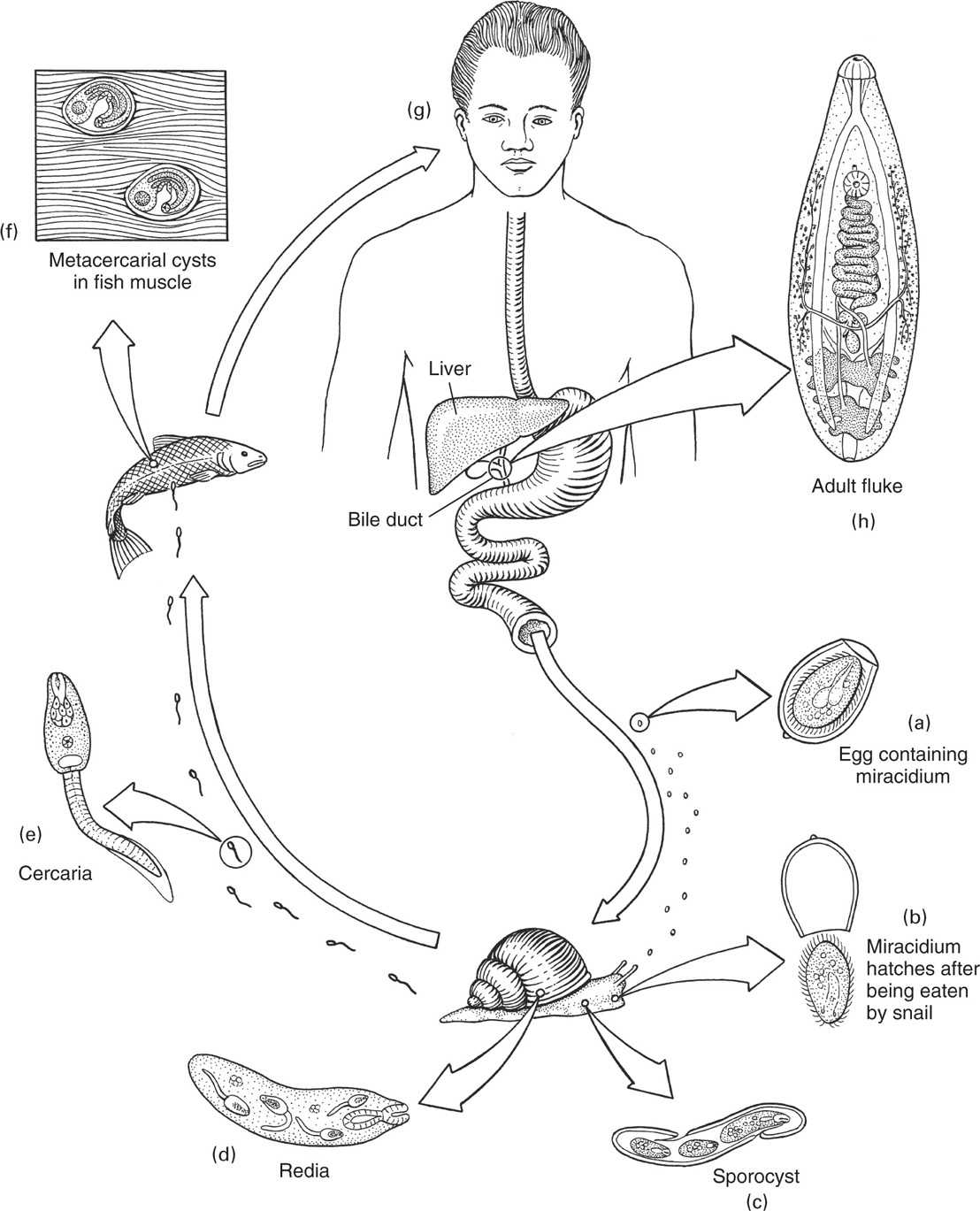

Several Paragonimus species may infect humans. Paragonimus westermani, which is widely distributed in East Asia, is the species most frequently involved. The short, plump (10 by 5 mm), reddish-brown adults are characteristically found encapsulated in the pulmonary parenchyma of their definitive host. The adults are often, but not always, found in pairs in these capsules, where they usually cross-fertilize each other. Here they deposit operculated, golden-brown eggs, which are distinguished from similar structures by their size (50 by 90 μm) and prominent periopercular shoulder (Figure 57–1). Eggs may be released into a bronchiole before the capsule of human fibrous tissue is complete, or when a capsule erodes into a bronchiole. The eggs are then coughed up and spat out or swallowed and passed in the stool. In either case, if they reach fresh water, they embryonate for several weeks before the ciliated miracidia emerge through the open opercula. After invasion of an appropriate snail host, 3 to 5 months pass before cercariae are released. These larval forms invade the gills, musculature, and viscera of certain crayfish or freshwater crabs; over 6 to 8 weeks, the cercariae transform into metacercariae. When the raw or undercooked flesh of the second intermediate host is ingested by humans, the meta-cercariae encyst in the duodenum and burrow through the gut wall into the peritoneal cavity. Most then continue their migration through the diaphragm and reach maturity in the lungs 5 to 6 weeks later (Figure 57–2). However, some are retained in the intestinal wall and mesentery or wander to other foci such as the liver, pancreas, kidney, skeletal muscle, or subcutaneous tissue. Young worms migrating through the neck and jugular foramen may encyst in the brain, the most common ectopic site. Paragonimiasis is a zoonosis: In addition to humans, other carnivores may serve as definitive hosts, including the rat, cat, dog, and pig. Immature ectopic adults in the striated muscles of the pig may infect humans after ingestion of undercooked pork.

FIGURE 57–1. Trematode eggs. A. Structure of Paragonimus and Clonorchis adults and ova. B. Structure of Fasciola and Schistosoma adults and ova. C. Two Clonorchis sinensis eggs in stool. The left egg has an open operculum to hatch a transparent miracidium. D. Mature S mansoni egg in stool with lateral spine. (C and D, Reproduced with permission from Connor DH, Chandler FW, Schwartz DQ, et al: Pathology of Infectious Diseases. Stamford CT: Appleton & Lange, 1997.) E. Mature S haematobium egg in urine with terminal spine. F. Mature S japonicum egg in stool with diminutive spine. (E and F provided by Paul Pottinger, M.D.)

FIGURE 57–2. Life cycle of Paragonimus westermani. (Reproduced with permission from Roberts RL, Janovy J, Nadler S: Foundations of Parasitology, 9th edition. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

Adults usually encapsulate in lung

Capsule erodes into bronchiole and eggs are coughed up; cycle continues if eggs reach water with susceptible snail

Crayfish and freshwater crabs are second intermediate hosts

Other carnivores are also definitive hosts

![]() PARAGONIMIASIS (LUNG FLUKE INFECTION)

PARAGONIMIASIS (LUNG FLUKE INFECTION)

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Although most of the 5 million human infections are concentrated in the Far East (eg, Korea, Japan, China, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Indonesia), paragonimiasis has been described in India, Africa (P africanus), and Latin America (P mexicanus). Paragonimus kellicotti, a parasite of mink, is widely distributed in eastern Canada and the United States but rarely produces human infection. Approximately 1% of recent Vietnamese immigrants to the United States were once found to be infected with P westermani. Infection of the snail host, which is typically found in small mountain streams located away from human habitation, is probably maintained by animal hosts other than humans. Human disease occurs when food shortages or local customs expose individuals to infected crabs. When these crustaceans are prepared for cooking, juice containing metacercariae may be left behind on the working surface and contaminate other foods subsequently prepared in the same area. Fresh crab juice, which has been used for the treatment of infertility in Cameroon and of measles in Korea, may also transmit the disease. In the Far East, crabs are frequently eaten after they have been lightly salted, pickled, or immersed briefly in wine (drunken crab), practices that are seldom lethal to the metacercariae. This has occurred in the United States as well. Children living in endemic areas may be infected while handling or ingesting crabs during the course of play.

Infected snails often found in mountain streams

Humans infected by ingesting undercooked infected crustaceans

PARAGONIMIASIS (LUNG FLUKE INFECTION): CLINICAL ASPECTS

PARAGONIMIASIS (LUNG FLUKE INFECTION): CLINICAL ASPECTS

MANIFESTATIONS

Adult worms in the lung elicit an eosinophilic inflammatory reaction and, eventually, the formation of a 1 to 2 cm fibrous capsule that surrounds and encloses one or more parasites. An infected patient may harbor more than 20 such lesions. With the onset of oviposition, the capsule swells and erodes into a bronchiole, resulting in expectoration of the brownish eggs, blood, and an inflammatory exudate. Secondary bacterial infection of the evacuated cysts is common, producing a clinical picture of chronic bronchitis or bronchiectasis. When cysts rupture into the pleural cavity, chest pain and effusion can result.

Multiple lung cysts may form

Early in infection, chest X-rays demonstrate small segmental infiltrates; these are gradually replaced by round nodules that may cavitate. Eventually, cystic rings, fibrosis, and calcification occur, producing a picture closely resembling that of pulmonary tuberculosis. This confusion is compounded by the frequent coexistence of the two diseases.

Secondary infection of ruptured cysts produces bronchitis

Adult flukes in the intestine and mesentery produce pain, bloody diarrhea, and occasionally palpable abdominal or cutaneous masses; the latter is more characteristic of a related Chinese fluke, P skrjabini. In approximately 1% of the cases of paragonimiasis in Southeast Asia, more commonly in children, parasites lodge in the brain and produce a variety of neurologic manifestations, including epilepsy, paralysis, homonymous hemianopsia, optic atrophy, and papilledema.

Chronic pulmonary abscess may resemble tuberculosis

DIAGNOSIS

Eggs are usually absent from the sputum during the first 3 months of overt infection; however, repeated examinations eventually demonstrate them in more than 75% of infected patients. When a pleural effusion is present, it should be checked for eggs. Stool examination is frequently helpful, particularly in children who swallow their expectorated sputum. Approximately 50% of patients with brain lesions demonstrate calcification on X-ray films of the skull. The cerebrospinal fluid in such cases shows elevated protein levels and eosinophilic leukocytosis. A diagnosis in these cases, however, often depends on the detection of circulating antibodies via immunoblot technique. Their presence usually correlates well with acute disease and eventually disappears with successful therapy.

Eggs difficult to find in sputum, pleural fluid, and feces

Serology to make diagnosis and monitor treatment response

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION

Lung fluke infection responds well to praziquantel or bithionol (not available in the United States) therapy. Brain lesions may require anti-seizure medications. Control requires adequate cooking of shellfish before ingestion.

CLONORCHIS

![]() CLONORCHIS SINENSIS: PARASITOLOGY AND LIFE CYCLE

CLONORCHIS SINENSIS: PARASITOLOGY AND LIFE CYCLE

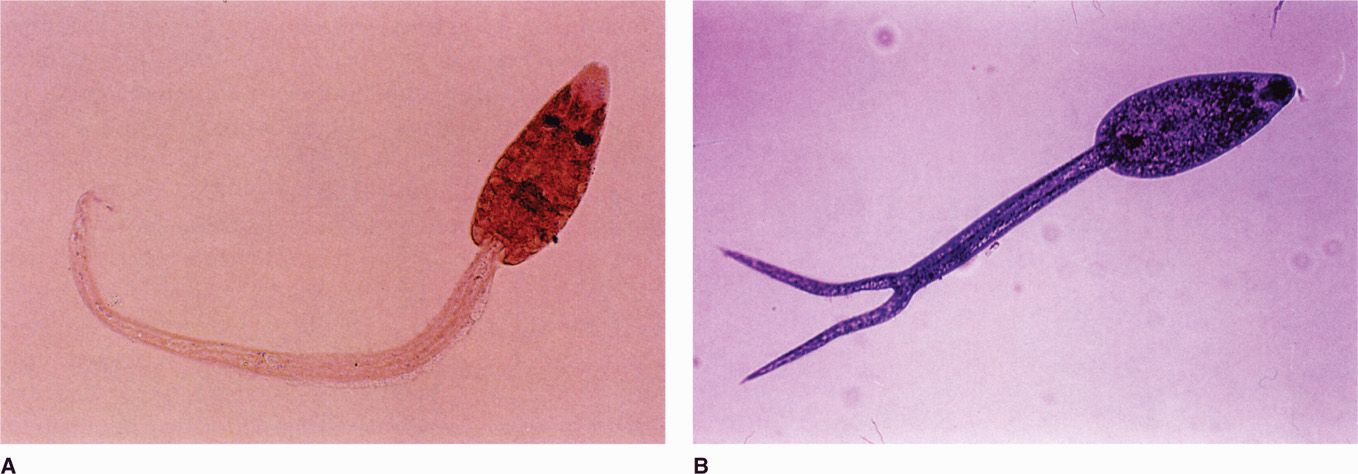

Flukes of the genera Fasciola, Opisthorchis, and Clonorchis all may infect the human biliary tract and at times produce manifestations of ductal obstruction (Table 57–2). Clonorchis sinensis, the Chinese liver fluke, is the most important and is discussed here. The small, slender (5 by 15 mm) adult survives up to 50 years in the biliary tract of its host by feasting on its rich mucosal secretions. A cone-shaped anterior pole, a large oral sucker, and a pair of deeply lobular testes arranged one behind the other in the posterior third of the worm distinguish it from other hepatic parasites (Figure 57–1A). Approximately 2000 tiny (15 by 30 μm) ovoid eggs are discharged daily and find their way down the bile duct and into the fecal stream. The urn-shaped eggshells have a discernible shoulder at their opercular rim and a tiny knob on the broader posterior pole (Figure 57–1A). On reaching fresh water, they are ingested by their intermediate snail host, where they transform into cercariae (Figure 57–3A). These cercariae are released into the water, where they swim until they penetrate the tissues of freshwater fish, in which they encyst to form metacercariae. If the latter host is ingested by a fish-eating mammal, the larvae are released in the duodenum, ascend the common bile duct, migrate to the second-order bile ducts, and mature to adulthood over 30 days (Figure 57–4).

FIGURE 57–3. Trematode cercarial larvae. A. Clonorchis sinensis. B. Schistosoma mansoni. (Reproduced with permission from Connor DH, Chandler FW, Schwartz DQ, et al: Pathology of Infectious Diseases. Stamford CT: Appleton & Lange, 1997.)

FIGURE 57–4. Life cycle of Clonorchis. (Reproduced with permission from Roberts RL, Janovy J, Nadler S: Foundations of Parasitology, 9th edition. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

Adults survive decades in biliary tract

Eggs discharged in bile ducts appear in feces

Snails are first intermediate host; fish the second

Metacercariae from ingested fish migrate to biliary system

In addition to humans, rats, cats, dogs, and pigs may serve as definitive hosts.

![]() CLONORCHIASIS (LIVER FLUKE INFECTION)

CLONORCHIASIS (LIVER FLUKE INFECTION)

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Clonorchiasis is endemic in Southeast Asia, particularly in Korea, Japan, Taiwan, the Red River Valley of Vietnam, the Southern Chinese province of Guandong, and Hong Kong. In previous years, parasite transmission was perpetuated by the practice of fertilizing commercial fish ponds with human feces. Recent improvements in the disposal of human waste have diminished acquisition of the disease in most areas. However, the extremely long life span of these worms is reflected in a much slower decrease in the overall infection prevalence. In some villages in southern China, virtually the entire adult population is infected. A survey of stool specimens from immigrants from Hong Kong to Canada showed an infection rate of more than 15% overall and 23% in adults between 30 and 50 years of age. Clonorchiasis is acquired by eating raw, frozen, dried, salted, smoked, or pickled fish. Commercial shipment of such products outside of the endemic area may result in the acquisition of worms far from their original source.

Endemic in Southeast Asia

Transmission to humans related to waste disposal

Ingestion of uncooked fish infects humans

CLONORCHIASIS (LIVER FLUKE INFECTION): CLINICAL ASPECTS

CLONORCHIASIS (LIVER FLUKE INFECTION): CLINICAL ASPECTS

MANIFESTATIONS

Migration of the larvae from the duodenum to the bile duct may produce fever, chills, mild jaundice, eosinophilia, and liver enlargement. The adult worm induces epithelial hyperplasia, adenoma formation, and periductal inflammation. In light infection, clinical disease seldom results. However, numerous reinfections may produce worm loads of 500 to 1000, resulting in the formation of bile stones and sometimes bile duct carcinoma in patients with severe, long-standing infections. Calculus formation is often accompanied by asymptomatic biliary carriage of Salmonella serovar Typhi. Dead worms may obstruct the common bile duct and induce secondary bacterial cholangitis, which may be accompanied by bac-teremia and endotoxic shock. Occasionally, adult worms are found in the pancreatic ducts, where they can produce ductal obstruction and acute pancreatitis.

Light infection usually asymptomatic

Severe hepatic and biliary manifestations from heavy worm loads, including cholangiocarcinoma

DIAGNOSIS

Definitive diagnosis of clonorchiasis requires the recovery and identification of the distinctive egg from the stool or duodenal aspirates. In mild infections, repeated examinations may be required. Because most patients are asymptomatic, any individual with clinical manifestations of disease in whom Clonorchis eggs are found should be evaluated for the presence of other causes of illness. In acute symptomatic clonorchiasis, there is usually leukocytosis, eosinophilia, elevation of alkaline phosphatase levels, and abnormal computed tomography and ultrasonographic liver scans. Cholangiograms may reveal dilatation of the intrahepatic ducts, small filling defects compatible with the presence of adult worms, and occasionally cholangiocarcinoma.

Distinctive eggs present in feces and duodenal aspirates

Eosinophilia common in acute disease

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION

Praziquantel and albendazole have proved to be effective therapeutic agents. Patients with acute obstructive cholangitis due to a worm or stone in the large collecting ducts should be managed as for any other cause of obstruction, including consideration of antibiotics for secondary infection and correction of the obstruction [eg, via endoscopic retrograde pancreatography cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)]. Prevention requires thorough cooking of freshwater fish and appropriate sanitary disposal of human feces.

SCHISTOSOMA

![]() SCHISTOSOMA SPECIES: PARASITOLOGY AND LIFE CYCLE

SCHISTOSOMA SPECIES: PARASITOLOGY AND LIFE CYCLE

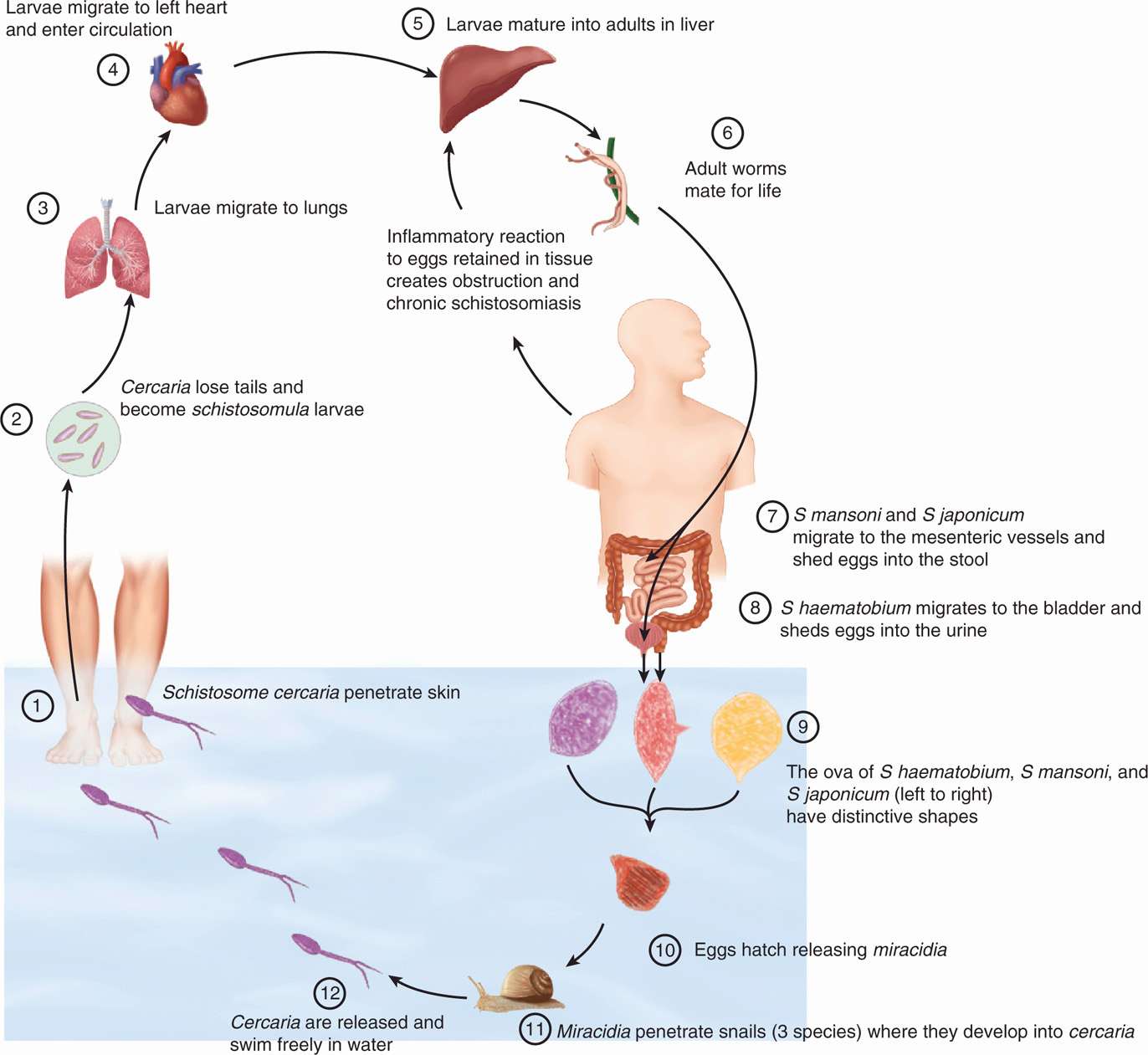

The schistosomes are a group of closely related flukes that inhabit the vascular system of a number of animals. Of the five species known to infect humans, S mansoni, S haematobium, and S japonicum are of primary importance. They infect 200 to 300 million persons in Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, and South America, and kill 1 million annually. The remaining two species are found in limited areas of West Africa (S intercalatum) and Southeast Asia (S mekongi), and are not discussed here in detail.

Adults inhabit portal vascular system

The adult worms can be distinguished from the hermaphroditic trematodes by the anterior location of their ventral sucker, by their cylindric bodies, and by their reproductive systems (ie, separate sexes). Adult specimens of different species are differentiated from one another only with difficulty. The 1 to 2 cm male possesses a deep ventral groove, or “schist.” Within this gynecophoral canal it carries the longer, more slender female in lifelong copulatory embrace. The schistosome life cycle (Figure 57–5) begins after mating in the hepato-portal circulation when the conjoined couple uses their suckers to ascend the mesenteric vessels against the flow of blood. Guided by unknown stimuli, S japonicum enters the superior mesenteric vein, eventually reaching the venous radicals of the small intestine and ascending colon; S mansoni and S haematobium are directed to the inferior mesenteric system. The destination of the former is the descending colon and rectum; the latter, however, passes through the hemorrhoidal plexus to the systemic venous system, ultimately coming to rest in the venous plexus of the bladder and other pelvic organs.

FIGURE 57–5. Life cycle of schistosomes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree