Clinical effects depend on whether humans are definitive hosts or intermediate hosts

Tissue cysts, not intestinal worms, cause serious disease

![]() PARASITOLOGY

PARASITOLOGY

MORPHOLOGY

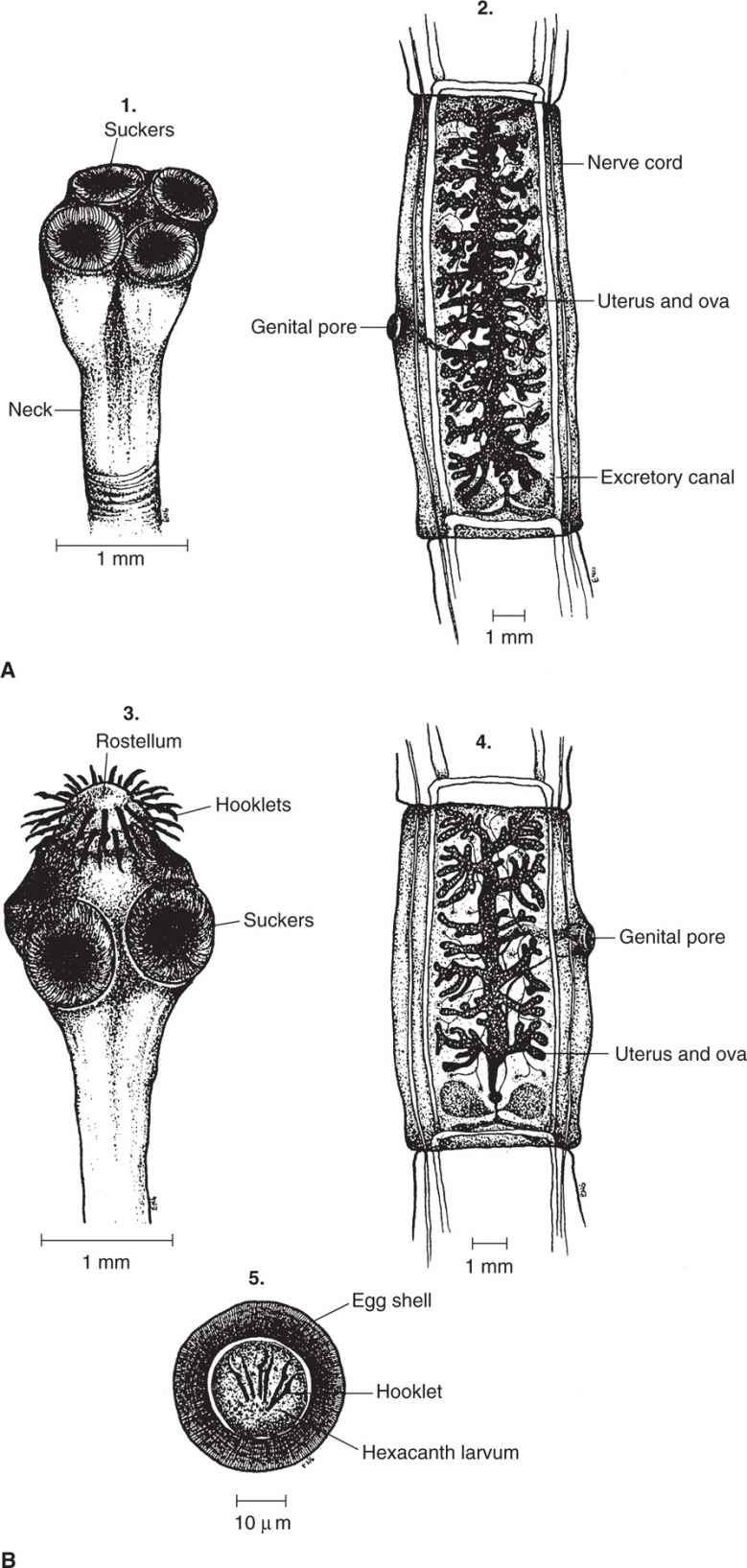

Like all helminths, tapeworms lack vascular and respiratory systems. In addition, they are devoid of both gut and body cavity. Food is absorbed across a complex cuticle, and the internal organs are embedded in solid parenchyma. The adult is divided into three distinct parts: The “head” or scolex; a generative “neck”; and a long, segmented body called the strobila. The scolex typically measures less than 2 mm in diameter and is equipped with four muscular sucking disks used to attach the worm to the intestinal mucosa of its host. (In one genus, Diphyllobothrium, the disks are replaced by two grooves called bothria.) As a further aid in attachment, the scolex of some species possesses a retractable protuberance, or rostellum, armed with a crown of chitinous hooks. Immediately posterior to the scolex is the neck from which individual segments, or proglottids, are generated one at a time to form the chain-like body. Each proglottid is a self-contained hermaphroditic reproductive unit joined to the remainder of the colony by a common cuticle, nerve trunks, and excretory canals. Its male and female gonads mature and self-fertilize as the segment is pushed farther and farther from the neck by the formation of new proglottids. When the segment reaches gravidity, it releases its eggs by rupturing, disintegrating, or passing them through its uterine pore.

No gut; food absorbed from host

Divided into scolex, neck, and segmented body parts

Each proglottid a hermaphroditic unit releasing eggs via rupture or through uterine pore

BEEF TAPEWORM

![]() TAENIA SAGINATA: PARASITOLOGY AND LIFE CYCLE

TAENIA SAGINATA: PARASITOLOGY AND LIFE CYCLE

Taenia saginata inhabits the human jejunum, where it may live for up to 25 years and grow to a maximum length of 10 m. Its 1 mm scolex lacks hooklets but possesses the four sucking disks typical of most cestodes (Figure 56–1A). The creamy white strobila consists of 1000 to 2000 individual proglottids. The terminal segments are longer (20 mm) than they are wide (5 mm), and contain a large uterus with 15 to 20 lateral branches; these characteristics are useful in differentiating them from those of the closely related pork tapeworm, T solium (see below). When fully gravid, strings of six to nine terminal proglottids, each containing approximately 100 000 eggs, break free from the remainder of the strobila. These muscular segments may crawl unassisted through the anal canal or be passed intact with the stool. Proglottids reaching the soil may remain motile for a short time, perhaps in order to move away from human feces and into fresh grass that will entice a cow during grazing. Eventually the proglottids disintegrate, releasing their distinctive eggs. These eggs are 30 to 40 μm in diameter, spherical, and possess a thick, radially striated shell (Figure 56–1B). In appropriate environments, the embryo may survive in the egg for months. If ingested by cattle or certain other herbivores, the embryo is released, penetrates the intestinal wall, and is carried by the vascular system to the striated muscles of the tongue, diaphragm, and hindquarters. Here it transforms into a white, ovoid (5 by 10 mm) cysticercus (Cysticercus bovis). When present in large numbers, cysticerci impart a spotted or “measly” appearance to the flesh. Humans are infected when they ingest inadequately cooked meat containing these larval forms, which evaginate into scolices, attach to the jejunal epithelium, and begin to grow into a full-sized adult tapeworm, thus completing the life cycle.

FIGURE 56–1. Tapeworm structures. A. Taenia saginata. B. Taenia solium. (1, 3) scolices; (2, 4) gravid proglottids; (5) ova (indistinguishable between species).

Taenia saginata inhabits human jejunum (humans definitive hosts)

Gravid proglottids passed in human stool

Eggs ingested by herbivore intermediates (cows intermediate hosts)

Eggs transform into cysticerci in striated muscle of cow

Humans infected by eating inadequately cooked infected meat

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In the United States, sanitary disposal of human feces and federal inspection of meat have nearly interrupted transmission of T saginata. At present, less than 1% of examined carcasses are infected. Nevertheless, bovine cysticercosis is still a significant problem in the southwestern area of the country, where cattle become infected in feedlots or while pastured on land irrigated with human sewage or worked by infected laborers who have insufficient access to sanitary facilities. Shipment of infected carcasses can result in human infection in other areas of the United States. In countries where sanitary facilities are less comprehensive and undercooked or raw beef is eaten, T saginata is highly prevalent. Examples include Kenya, Ethiopia, the Middle East, the former Yugoslavia, and parts of the former Soviet Union and South America.

Indigenously acquired disease rare in United States

BEEF TAPEWORM DISEASE: CLINICAL ASPECTS

BEEF TAPEWORM DISEASE: CLINICAL ASPECTS

MANIFESTATIONS

Most persons infected with beef tapeworm are asymptomatic and become aware of the infection only through the spontaneous passage of proglottids. The proglottids may be observed on the surface of the stool or appear in the underclothing or bedsheets of the alarmed host. Passage may occur very irregularly and can be precipitated by excessive alcohol consumption. Some patients report epigastric discomfort, nausea, irritability (particularly after passage of segments), diarrhea, and weight loss. Occasionally, the proglottids may obstruct the appendix, biliary duct, or pancreatic duct.

Clinical symptoms usually mild

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of beef tapeworm disease is made by finding eggs or proglottids in the stool. Eggs may also be distributed on the perianal area secondary to rupture of proglottids during anal passage. The adhesive cellophane tape technique described for pinworm can be used to recover the worms from this area. With this procedure, 85% to 95% of infections are detected, in contrast to only 50% to 75% by stool examination. Because the eggs of T solium and T saginata are morphologically identical, it is necessary to examine a proglottid to identify the species correctly. As discussed below, the implications and management of these two infections may be substantially different.

Adhesive cellophane tape technique and stool examination detect eggs and proglottids

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION

The drugs of choice are praziquantel or niclosamide (not available in the United States), which act directly on the worm. Both are highly effective in single-dose oral preparations, but to ensure cure, fecal specimens should be examined again approximately 3 months following treatment. Ultimately, control is best achieved through the sanitary disposal of human feces. Meat inspection is helpful; the cysticerci are readily visible. In areas where the infection is common, thorough cooking is the most practical method of control. Internal temperatures of 56°C or more for 5 minutes or longer destroy the cysticerci. Salting or freezing for 1 week at –15°C or below is also effective.

Sewage disposal, meat inspection, and adequate cooking

PORK TAPEWORM

![]() TAENIA SOLIUM: PARASITOLOGY AND LIFE CYCLE

TAENIA SOLIUM: PARASITOLOGY AND LIFE CYCLE

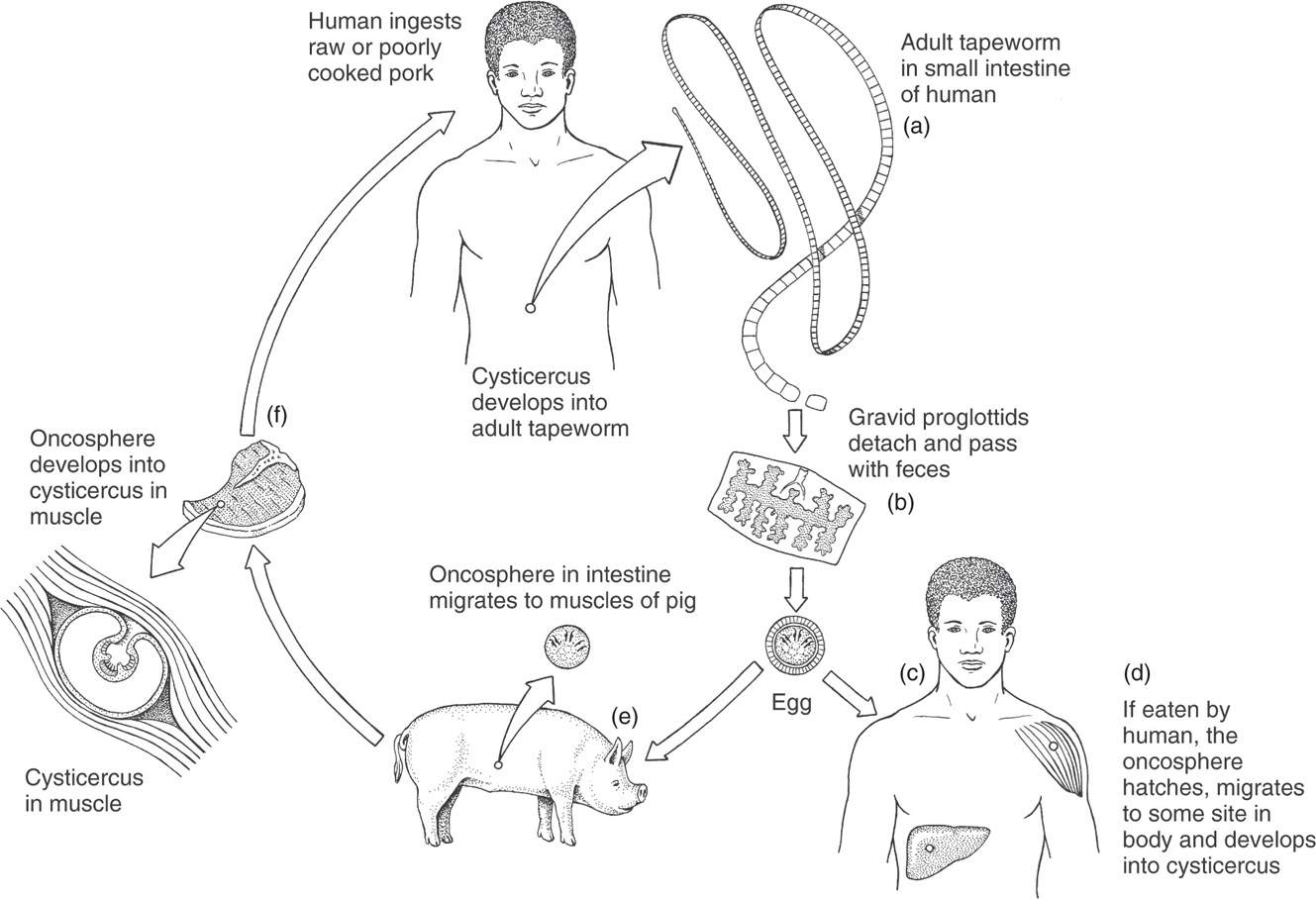

Like the beef tapeworm, which it closely resembles, T solium inhabits the human jejunum, where it may survive for decades. It can be distinguished from its close relative only by careful scrutiny of the scolex and proglottids; T solium possesses a rostellum armed with a double row of hooklets (Figure 56–1B3). The strobila is generally smaller than that of T saginata, seldom exceeding 5 m in length or containing more than 1000 proglottids. Gravid segments measure 6 by 12 mm and thus appear less elongated than those of the bovine parasite (Figure 56–1B4). Typically, the uterus has only 8 to 12 lateral branches. Although the eggs appear morphologically identical to those of T saginata, they are infective only to swine and—perhaps reflecting a genetic proximity we might prefer to overlook—humans. Both pigs and people may become intermediate hosts when they ingest food contaminated with viable eggs (Figure 56–2). Humans may be autoinfected when gravid proglottids are carried backward into the stomach during the act of vomiting, initiating the release of the contained eggs. However, autoinfection probably results more commonly from the transport of eggs from the perianal area to the mouth on contaminated fingers. The pork tapeworm life cycle is illustrated in Figure 56–2.

FIGURE 56–2. Pork tapeworm life cycle. (Reproduced with permission from Roberts RL, Janovy J, Nadler S: Foundations of Parasitology, 9th edition. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

Taenia solium strobila shorter than in T saginata

Humans infected by eating undercooked pork cysts (humans definitive hosts)

Added complexity: Eggs also infective to swine and to humans (humans are also intermediate hosts)

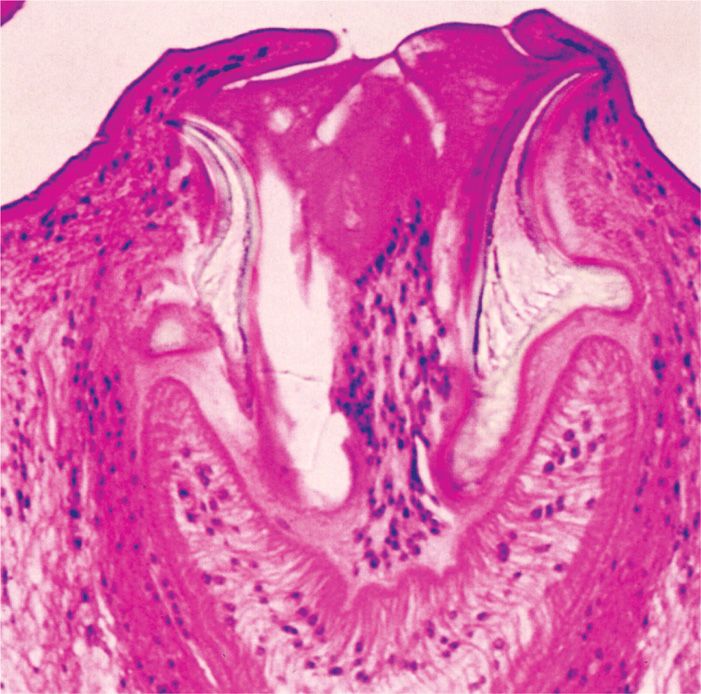

Regardless of the route of entry, an egg reaching the stomach of an appropriate intermediate host hatches, releasing an embryo called a “hexacanth,” because it has six hooklets. The embryo penetrates the intestinal wall and may be carried by the lymphohematogenous system to any tissue in the body. There it develops into a 1 cm, white, opalescent cysticercus over 3 to 4 months (Figure 56–3). The cysticercus may remain viable in pigs for up to 5 years, eventually infecting humans when they ingest undercooked “measly” flesh. The scolex everts, attaches to the mucosa, and develops into a new adult worm, thereby completing the cycle. In infected humans, the cysts fail to complete the life cycle; however, they may cause seizures if they form in the brain.

FIGURE 56–3. Cysticercosis of muscle. This section shows a cysticercus with the hooklets of a worm scolex. (Reproduced with permission from Connor DH, Chandler FW, Schwartz DQ, et al: Pathology of Infectious Diseases. Stamford CT: Appleton & Lange, 1997.)

Significant difference from beef tapeworm: Tissue cysticerci develop in swine and humans

In summary, patients will acquire pork tapeworms if they consume undercooked pork; they will acquire cysticercosis if they consume tapeworm eggs.

Mantra of T solium: “Eat a cyst, get a worm … Eat an egg, get a cyst”

![]() PORK TAPEWORM DISEASE

PORK TAPEWORM DISEASE

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Although infected swine are still occasionally found in the United States, most human disease is found in immigrants from endemic areas. Although pork tapeworm disease is widely distributed throughout the world, it is particularly common in South and Southeast Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe.

Taenia solium rarely found in U.S. domestic swine

PORK TAPEWORM DISEASE: CLINICAL ASPECTS

PORK TAPEWORM DISEASE: CLINICAL ASPECTS

MANIFESTATIONS

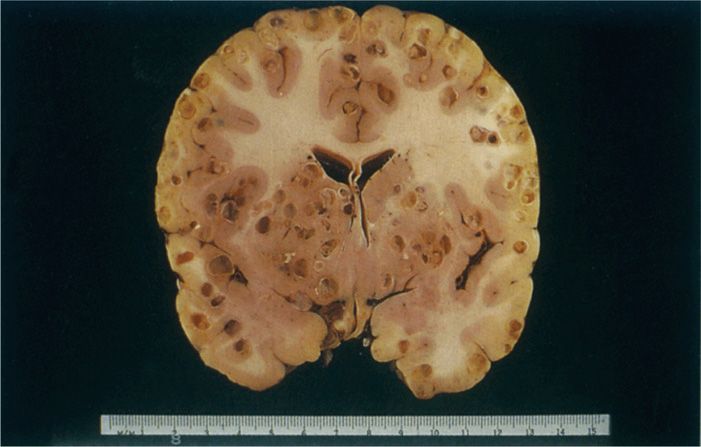

The signs and symptoms of infection with the adult worm are mild and similar to those of T saginata taeniasis. However, clinical manifestations are totally different when humans serve as intermediate hosts. Cysticerci develop in the subcutaneous tissues, muscles, heart, lungs, liver, eye, and brain (Figure 56–4). As long as the number is small and the cysticerci remain viable, tissue reaction is moderate and the patient is typically asymptomatic. The death of the larva, however, may lead to a marked inflammatory reaction, fever, muscle pains, and eosinophilia.

FIGURE 56–4. Cysticercosis of brain. This brain from a 16-year-old girl shows multiple cysticercal cysts primarily at the junction of white and gray matter. (Reproduced with permission from Connor DH, Chandler FW, Schwartz DQ, et al: Pathology of Infectious Diseases. Stamford CT: Appleton & Lange, 1997.)

Major clinical manifestations caused by reaction to cysticerci

The most important and dramatic clinical presentation of cysticercosis results from lesions in the central nervous system (CNS). During the acute invasive stage, patients may experience fever, headache, and eosinophilia. In heavy infections, a meningoencephalitic syndrome with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) eosinophilic pleocytosis may be present. Established cysts can be found in the cerebrum, ventricles, subarachnoid space, spinal cord, and eye. Cerebral cysts are usually small, often measuring 2 cm or less in diameter; racemose (clustered) lesions may be threefold larger. Parenchymal infections can induce focal neurologic abnormalities, personality changes, intellectual impairment and/or seizures; in many endemic areas, cysticercosis is the leading cause of epilepsy. Subarachnoid lesions and cysticerci located within the fourth ventricle may obstruct the flow of CSF, producing increased intracranial pressure with its associated headache, vomiting, visual disturbances, or psychiatric abnormalities. Multiple lesions have a predilection for the basal cisterns. Spinal involvement produces cord compression or meningeal inflammation. Eye lesions incite pain and visual disturbances.

Meningoencephalitic syndrome with eosinophilia produced by CNS invasion

Multiple small cysts formed

Focal neurologic signs and epilepsy related to cysts

DIAGNOSIS

Infection with the adult worm is diagnosed as described for T saginata. Cysticercosis is suspected when an individual who has been in an endemic area presents with neurologic manifestations or subcutaneous nodules. Radiographs of the soft tissues often reveal dead, calcified cysticerci. Viable lesions may be detected as low-density masses by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Brain cysticerci typically are 5 to 10 mm in diameter (Figure 56–4). Subarachnoid lesions are often larger, may be lobulated, and are often “isodense,” making them difficult to identify radiographically. The lesions may resemble brain malignancy, which is managed differently, and thus it is important to confirm the diagnosis. This can be done by demonstrating the larva in a biopsy sample of a subcutaneous nodule or by detecting specific antibodies in the circulating blood. Serum and CSF enzyme immunoassays and western blot testing for specific anticysticercal antibodies have a sensitivity of 80% to 95%. The presence of IgG antibodies alone may reflect the presence of past or inactive disease.

Adult worm diagnosed from proglottids or eggs in stool

Imaging, biopsy, or serology required to diagnose cysticercosis

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION

Infection with the adult worm is approached in the manner described for T saginata. Symptomatic neurocysticercosis requires a different approach. For patients who present with seizures, antiepileptic medications are the most important priority; treatment of brain parenchymal lesions can then be attempted with praziquantel or albendazole and corticosteroids (to help minimize the inflammatory response to dying cysticerci). However, seizure control is the first priority. Mechanical blockage of the brain’s ventricles is another feared complication. Intraventricular, subarachnoid, and eye lesions appear relatively refractory to chemotherapy; surgery, CSF shunts, and corticosteroids may help ameliorate symptoms. Tapeworm acquisition can be prevented by adequately cooking pork before ingestion. Egg ingestion can be prevented by proper hand hygiene among food service workers after using the toilet.

Antiepileptic medications mainstay of treatment, with or without antiparasitics and corticosteroids

Surgery occasionally needed for cysticercosis

FISH TAPEWORM

![]() DIPHYLLOBOTHRIUM LATUM: PARASITOLOGY AND LIFE CYCLE

DIPHYLLOBOTHRIUM LATUM: PARASITOLOGY AND LIFE CYCLE

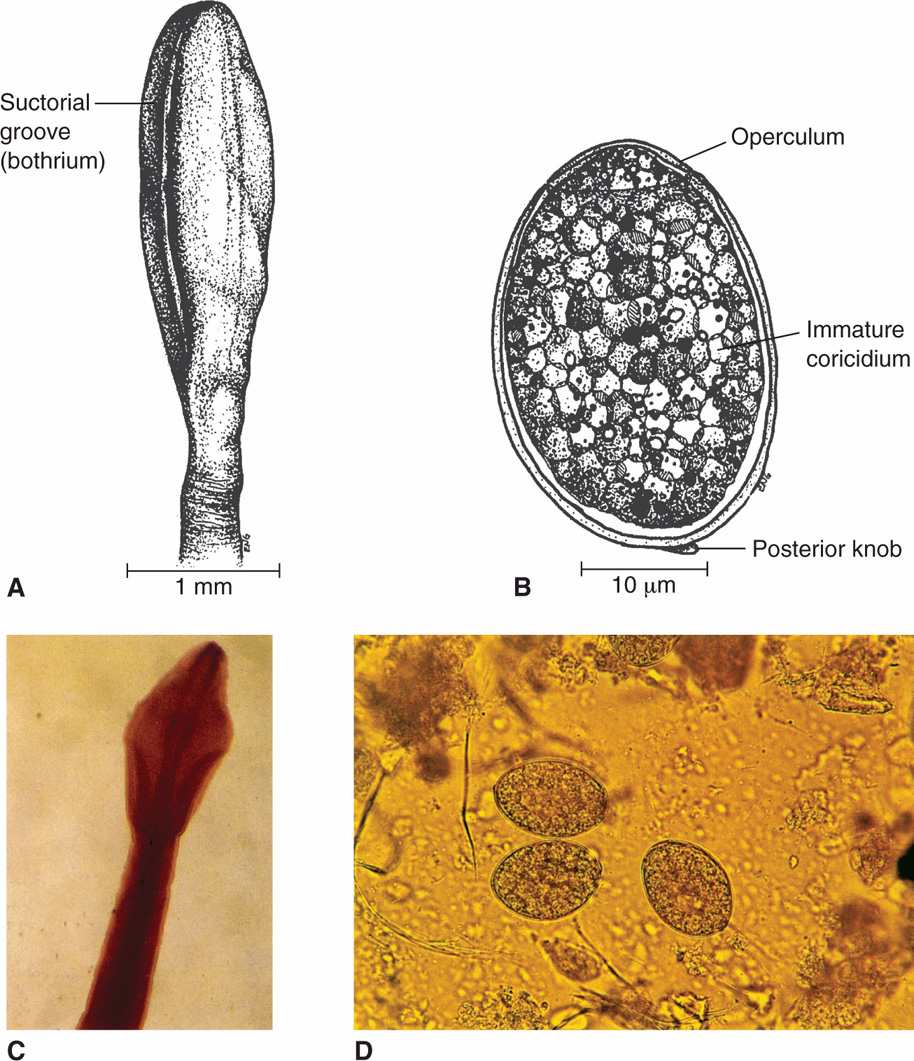

The adult D latum attaches to the human ileal mucosa with the aid of two sucking grooves (bothria) located in an elongated fusiform scolex (Figure 56–5). In life span and overall length, it resembles the Taenia species discussed previously. The 3000 to 4000 proglottids, however, are uniformly wider than they are long, accounting for this cestode’s species designation as well as one of its common names, the “broad tapeworm.” The gravid segments contain a centrally positioned, rosette-shaped uterus unique among the tapeworms of humans. Unlike those of the Taenia species, ova are released through the uterine pore. Over 1 million oval (55 by 75 μm) operculated eggs are released daily into the stool (Figure 56–5).

FIGURE 56–5. Diphyllobothrium latum. A. Structure of scolex. B. Structure of egg. C. Scolex from a human case. D. Ova in stool stained with iodine. (Reproduced with permission from Connor DH, Chandler FW, Schwartz DQ, et al: Pathology of Infectious Diseases. Stamford CT: Appleton & Lange, 1997.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree