OUTLINE

I. COLORS

A. Technically, a color additive is any dye, pigment, or substance that can impart color when added or applied to a food, drug, or cosmetic or to the human body.

B. Colors are substances added to drug products and preparations solely for imparting color.

1. They must be nontoxic and inactive pharmacologically.

2. Color additives that are permitted for general use may not be used in the area of the eye or in injections unless such use is specified in the color additive listing regulation. (1,2).

3. The use of colors must follow FDA regulations (1).

4. They should not be employed to disguise poor product quality.

C. Colors are added to improve patient acceptance of a product or preparation.

1. The color added to an oral dosage form is usually selected to coincide with or complement the flavor given to the preparation. For example, cherry-flavored preparations are usually colored red, orange-flavored preparations are colored orange, and mint-flavored preparations may be green or white.

2. Flesh-toned colors may be added to topical preparations so that the preparation blends with the color of the skin and is less visible.

3. Color matters because it is functional and subliminally and overtly communicates information and provides many other operational benefits. Viagra, a diamond-shaped blue pill, was introduced in 1997 and immediately became an overnight sensation. In 2002, the marketing groups of a rival product, Levitra, brainstormed the issue of color for their brand. Extensive market research found that consumers thought that the blue color was too cool and was equated with being sick. For this reason, Levitra’s manufacturers made Levitra’s color orange, an extremely vibrant and energetic color.

D. The colors used in pharmaceutical dosage forms are either natural colors or synthetic dyes.

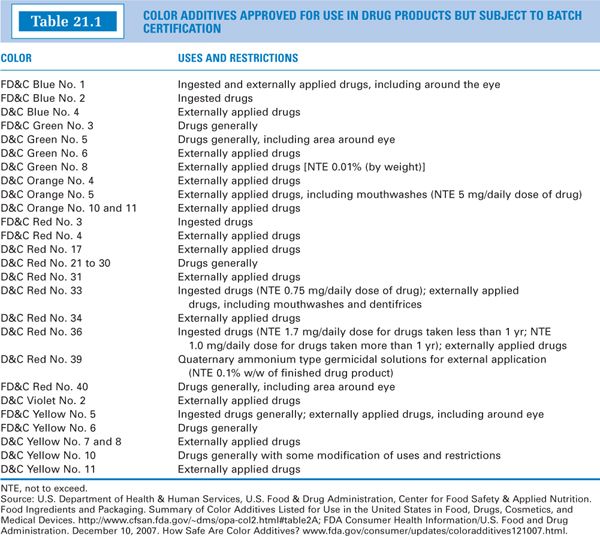

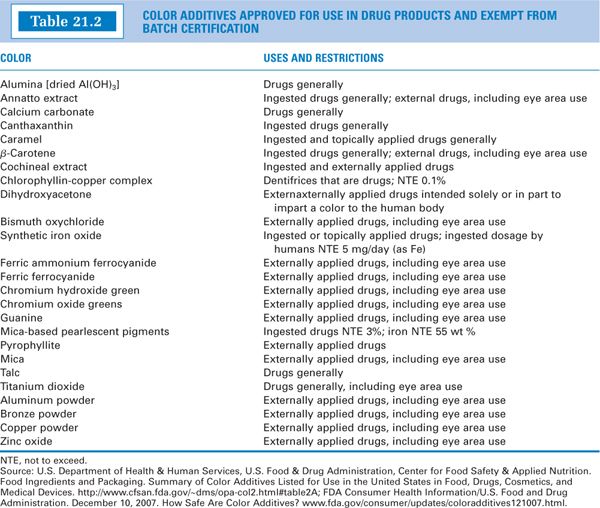

1. Two main categories make up the FDA’s list of permitted color additives (2). Certifiable color additives are human-made, derived primarily from petroleum and coal sources. Examples are listed in Table 21.1. Other color additives are “exempt” from batch certification. These are obtained largely from plant, animal, or mineral sources. Examples such as caramel color and grape color extract are listed in Table 21.2.

2. Approval of a color additive for one intended use does not mean approval for other uses. For example, no color additives have been approved for injection (2).

3. Natural colors that are used in drug products and preparations fall into two classes: mineral pigments and plant pigments.

a. Examples of mineral pigments include red ferric oxide, titanium oxide, and carbon black. Red ferric oxide is the red component that, when added to white zinc oxide powder, gives the pink-colored powder calamine. Titanium oxide is a white pigment that is often added to oral or topical preparations and cosmetics. It is also used in tablet coatings and in capsule shells to render them opaque.

b. Plant pigments include colors such as indigo, saffron, and beta-carotene.

4. Synthetic dyes

a. As their name indicates, synthetic dyes are chemically synthesized. The first dyes of this sort were synthesized from aniline; because aniline was extracted from coal tar, this whole class of colors is often referred to either as aniline dyes or coal tar dyes.

b. Synthetic dyes owe their colors to the presence of certain unsaturated groups called chromophores. Often conjugation of unsaturated systems is a requirement for color. The color of the dye or its intensity can be altered by the presence of other groups called auxochromes (3).

c. Dyes used in foods, drugs, and cosmetics must be certified by the FDA for such use, because the Federal Food, Drug, & Cosmetic (FD&C) Act of 1938 made food color additive certification mandatory and transferred the authority for its testing from the USDA to the FDA. To avoid confusing color additives used in food with those manufactured for other uses, three categories of certifiable color additives were created:

(1) Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C)—color additives with application in foods, drugs, or cosmetics;

(2) Drug and Cosmetic (D&C)—color additives with applications in drugs or cosmetics;

(3) External Drug and Cosmetic (External D&C)—color additives with applications in externally applied pharmaceutical dosage forms (e.g., ointments) and in externally applied cosmetics.

d. It is important to keep abreast of the current legal status of dyes used in drug products and preparations, because changes do occur. This is illustrated with the following examples.

(1) Amaranth, formerly certified FD&C Red #2, was at one time used extensively in processed food products and was the most frequently used dye in compounding pharmaceutical preparations. In 1976, it was banned from use in foods, drugs, and cosmetics.

(2) For prescription drugs for human use containing FD&C Yellow No. 5 that are administered orally, nasally, vaginally, or rectally, or for use in the area of the eye, the labeling shall bear the warning statement, “This product contains FD&C Yellow No. 5 (tartrazine), which may cause allergic-type reactions (including bronchial asthma) in certain susceptible persons. Although the overall incidence of FD&C Yellow No. 5 (tartrazine) sensitivity in the general population is low, it is frequently seen in patients who also have aspirin hypersensitivity” (4). This warning statement must appear in the precautions section of the labeling.

(3) The labeling for over-the-counter and prescription drug products intended for human use administered orally, nasally, rectally, or vaginally containing FD&C Yellow No. 6 shall specifically declare the presence of FD&C Yellow No. 6 by listing it using the name FD&C Yellow No. 6 (4).

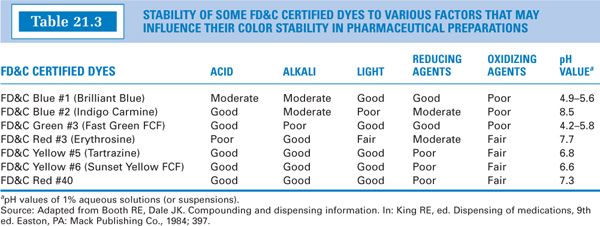

e. Dyes may be affected by changes in pH, and most are labile to either oxidation or reduction reactions. These changes may affect the dye’s solubility and its color or hue or may destroy its color all together. Table 21.3 lists several water-soluble FD&C certified dyes that are currently available from vendors of compounding drugs and chemicals. The table shows factors that affect the stability of each of these dyes (5). This information is helpful in selecting a particular dye for a dosage form being prepared.

5. Recommended dye concentrations for drug preparation

a. Appropriate concentrations of dye can best be determined by trial. The following general guidelines may be helpful.

b. Liquids

(1) The concentration of dye needed to impart a satisfactory color to a liquid drug preparation is so small that it is usually most convenient to make a stock solution of the dye and use a dropper or 1-mL syringe to measure the desired quantity.

(2) Color may develop with a concentration of 0.001% to 0.0005%; a tint may result with a concentration as low as 0.0001% (3).

(3) Rather than purchasing powdered dyes, some pharmacists find it more convenient to buy food coloring from the grocery store. These colors are FD&C approved and may be used for drug preparations. Their stability in the preparation, however, cannot be predicted unless the exact dye is specified on the label. Some labels do give this information.

c. Powders

A concentration of approximately 0.1% would give a pastel color to white powders (3). The dye should be incorporated using geometric dilution and trituration. Certifiable powder color additives are available as either “dyes” or “lakes.” Dyes dissolve in water and are manufactured as powders, granules, liquids, or other special-purpose forms. Lakes are the water-insoluble form of the dye. Lakes are more stable than dyes and are ideal for coloring preparations containing fats and oils or items lacking sufficient moisture to dissolve dyes.

II. FLAVORS AND SWEETENERS

A. Although intuitively we all know what flavor is, this characteristic is difficult to adequately define and quantify in precise terms. This is because flavor embodies a group of sensations including taste, smell, touch, sight, and even sound.

B. The human tongue has 10,000 taste buds. This means that even a single sensation such as taste is difficult to describe:Although the four primary tastes are sweet, sour, salty, and bitter, even a combination of these taste types could never be expected to describe the taste of a ripe strawberry or a frosty glass of root beer.

C. Flavors and sweeteners are added to oral dosage forms to improve patient acceptance of the preparation. Selecting a desirable flavor for a compounded drug preparation is important because patient compliance with a medication regimen may depend on the flavor of the drug preparation. This is especially true with children.

1. Flavors may be added to improve the palatability of a bland preparation or to mask the unpleasant taste of an active ingredient. Bitter is the most objectionable taste to patients and is, unfortunately, the most common taste for drugs.

2. As with coloring, determining the type and amount of flavor and sweetener is best done by trial.

3. When possible, selection of flavoring for a drug preparation should be done in consultation with the patient.

a. Flavor preference is somewhat age-related. Children tend to prefer sweet, fruity, and bubblegum-type flavors, whereas adults often favor such flavors as chocolate, coffee, licorice, maple, or butterscotch.

b. Flavors are also a matter of personal preference; for example, some patients love the taste of chocolate, whereas others dislike it. Although a certain flavor may do the best job of masking a particular drug taste, it is not useful if the intended patient dislikes that flavor.

c. Be aware that some patients associate bitter taste with drug potency and effectiveness.

d. Always check with patients for possible allergy to specific flavors.

4. Flavors are also often used to make medicines tasty for animals. For example, for birds, grape, molasses, orange, pina colada, and tutti-frutti are considered the best. For cats, beef, butterscotch, cheese, chicken, liver, molasses, peanut butter, salmon, sardine, and tuna seem most appropriate. Dogs prefer beef, cheese, chicken, liver, marshmallow, molasses, peanut butter, raspberry, and strawberry. Horses like alfalfa-, apple-, blue grass-, caramel-, cherry-, molasses-, and clover-flavored medications. Many exotic pets also prefer specific flavors. Ferrets like foods that taste like fish, fruits, and molasses, while gerbils, iguanas, and rabbits prefer fruit- or vegetable-flavored items (6).

D.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree