VIROLOGY

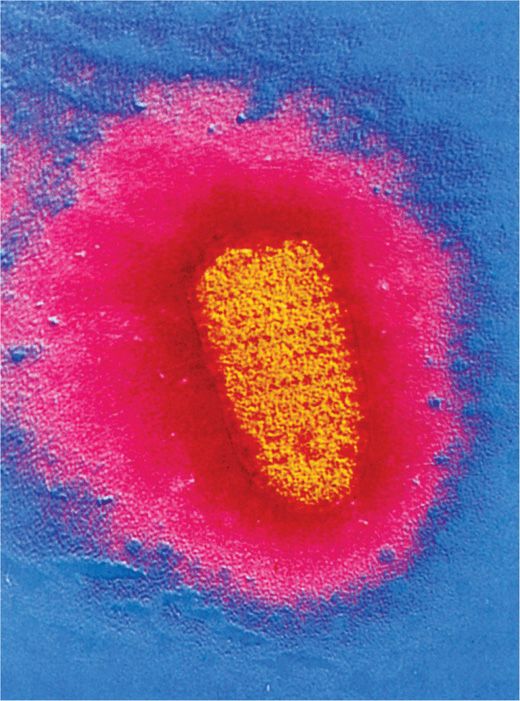

The rabies virus is a rhabdovirus, which is a bullet-shaped, enveloped, RNA virus, 70 nm in diameter × 180 nm in length, of the Lyssavirus genus and Rhabdoviridae family (Figure 17–1). The helical nucleocapsid (N) is composed of a single-stranded, negative-sense RNA genome and an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase enclosed in a matrix (M) protein covered by a lipid bilayer envelope containing knob-like glycoprotein (G). The knob-like glycoprotein excrescences, which elicit neutralizing and hemagglutination-inhibiting antibodies, cover the surface of the virion. In the past, a single antigenically homogeneous virus was believed to be responsible for all rabies; however, differences in cell culture growth characteristics of isolates from different animal sources (bats, cats, dogs, foxes, skunks), some differences in virulence for experimental animals, and antigenic differences in surface glycoproteins have indicated strain heterogeneity among rabies virus isolates. These studies may help to explain some of the biologic differences as well as the occasional case of “vaccine failure.” Other pathogens in the rhabdovirus group include vesicular stomatitis virus, which is an animal virus but may also occasionally infect humans (see Chapter 16).

FIGURE 17–1. Electron micrograph of the rabies virus (yellow) (×36,700). Note the bullet shape. The external surface of the virus contains spike-like glycoprotein projections that bind specifically to cellular receptors. (Reproduced with permission from Willey J, Sherwood L, Woolverton C (eds). Prescott’s Principles of Microbiology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008.)

Enveloped RNA virus is bullet shaped

Knob-like envelope glycoproteins elicit neutralizing and hemagglutination antibodies

Strains from different sources (animals) are antigenically heterogeneous

Rabies virus is transmitted from the bite of an animal (usually a rabid dog or wild animal) and multiplies initially at the site of entry in muscle cells, and then the virus travels to the CNS to replicate in the brain cells. Rabies virus G protein binds to the acetylcholine or neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) receptor present on the cell surface. The virus is internalized followed by fusion of the viral envelope with the endosomal membrane and uncoating and release of the nucleocapsid in the cytoplasm. Because rabies virus is a negative-sense RNA virus, virion-associated RNA-dependent RNA polymerase transcribes the genome to make several mRNAs in the cytoplasm. These mRNAs are translated into various proteins, including nucleocapsid, matrix, RNA polymerase, and G glycoproteins. The G glycoproteins are expressed on the infected cell surface membranes. After replication of viral RNA genomes directed by the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, the progeny virions are assembled in the cytoplasm. The nucleocapsid protein binds the RNA genome and packages the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. This nucleocapsid complex associates with the matrix protein, and the lipid bilayer envelope containing G protein is acquired as the progeny virions bud through the plasma membrane.

G protein binds to the acetylcholine or NCAM receptor on target cells

Negative sense RNA virus replicates in the cytoplasm

G protein-containing lipoprotein envelope acquired from plasma membrane

![]() RABIES

RABIES

EPIDEMIOLOGY

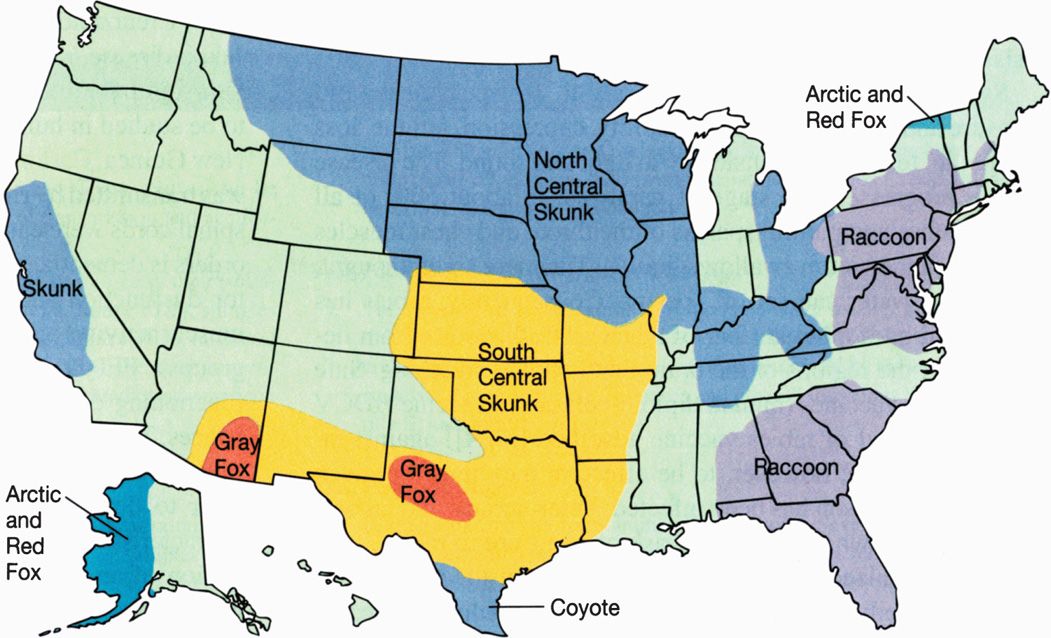

Rabies exists in two epizootic forms, urban and sylvatic. The urban form is associated with unimmunized dogs or cats, and the sylvatic form occurs in wild skunks, foxes, wolves, raccoons, and bats, but not rodents or rabbits. Introduction of an infected animal into a different geographic area can lead to infection of many new members of that species (Figure 17–2). For example, raccoon hunters apparently are to blame for the sudden appearance of raccoon rabies in West Virginia and Virginia in 1977. Before that time, the nearest cases of raccoon rabies were found several hundred miles away in South Carolina. The hunters are believed to have imported infected raccoons from another state. Since 1977, raccoon rabies has spread from West Virginia and Virginia to 12 northeastern states.

FIGURE 17–2. In the United States, rabies is found in terrestrial animals in 10 distinct geographic areas. In each area, a particular species is the reservoir, and one of five antigenic variants of the virus predominates as illustrated by the five different colors.

Two epizootic forms of rabies: urban (unimmunized dogs and cats) and sylvatic (wild bats, foxes, raccoons, skunks, wolves)

Human infection, or the much more common infection of cattle, is incidental, is blind ended, and does not contribute to maintenance or transmission of the disease. In the United States, more than 75% of reported cases of rabies in animals occur among wildlife. Human exposures may be from wild animals or from unimmunized dogs or cats. In recent years, there has been a decrease in US cases to less than two per year, and bat exposure has been the source in almost all cases despite a resurgence of rabies in skunks and raccoons. An occasional case has resulted from aerosol exposure (eg, bat caves and no bite). Domestic animal bites are very important sources of rabies in developing countries because of lack of enforcement of animal immunization. Infection in domestic animals usually represents a spillover from infection in wildlife reservoirs. Human infection tends to occur where animal rabies is common and where there is a large population of unimmunized domestic animals. Worldwide, the occurrence of human rabies is estimated to be more than 55 000 fatal cases per year mostly in Asia and Africa, with the highest attack rates in Southeast Asia, the Philippines, and the Indian subcontinent. Almost all of these cases result from dog bites. Human-to-human transmission of rabies has been documented via transplanted corneas and solid-organ transplantation. In theory, infected humans could potentially transmit rabies to uninfected humans via bite or nonbite, but such cases have not been reported.

Risks to humans in the United States are from bites of wild animals (bats, coyotes, foxes, raccoons, skunks, wolves, etc)

Aerosol spread from exposure in bat caves

More than 55 000 deaths mostly in Asia and Africa

Highest attack rates in Southeast Asia and Indian subcontinent, mostly from dog bites

Transmission from transplanted cornea and solid organ documented

PATHOGENESIS

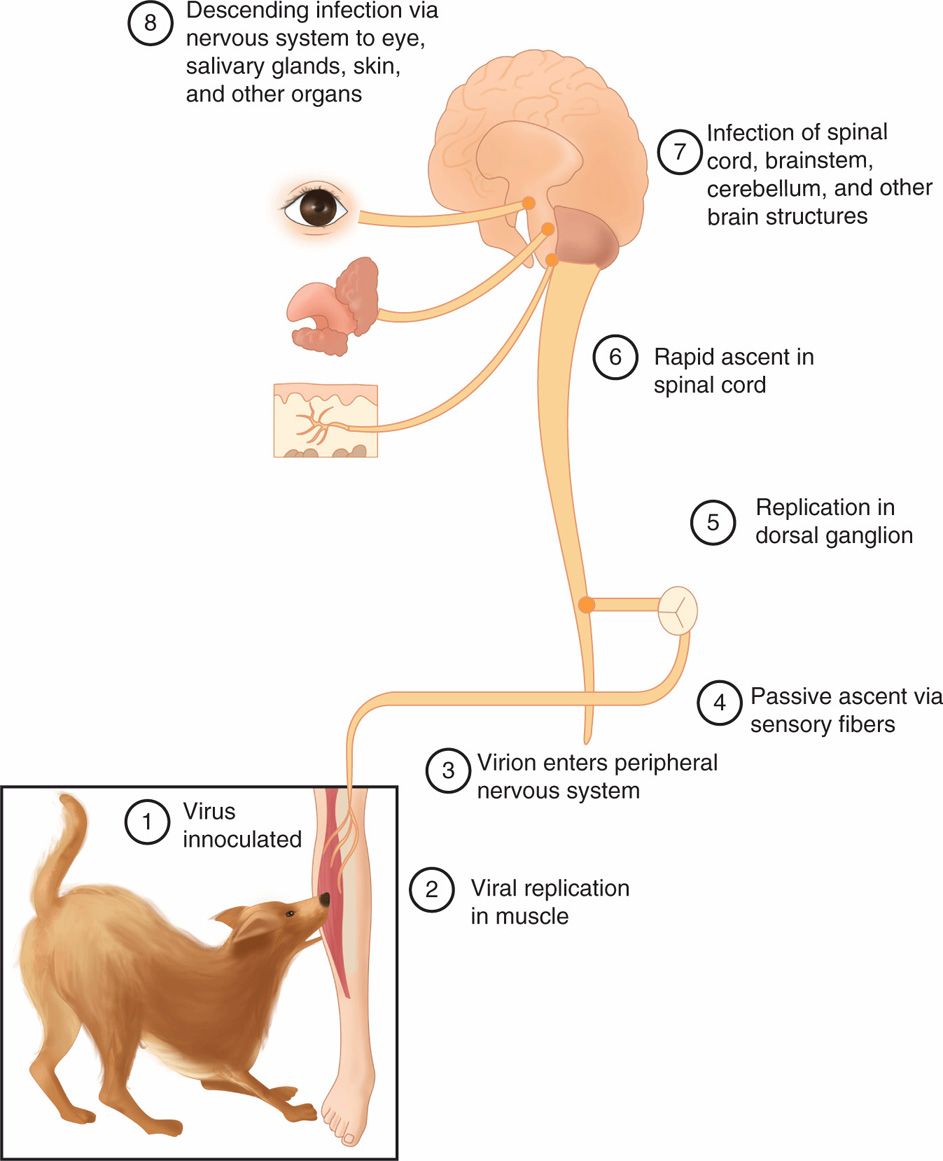

The sequence of events of the pathogenesis of rabies virus infection is depicted in Figure 17–3. The essential first event in human or animal rabies infection is the inoculation of virus through the epidermis, usually as a result of an animal bite. Inhalation of heavily contaminated material, such as bat droppings, can also cause infection. The incubation period is between 10 days and 1 year (average 20-90 days). Rabies virus first replicates in striated muscle tissue at the site of inoculation. Immunization at this time is presumed to prevent migration of the virus into neural tissues. In the absence of immunity, the virus then enters the peripheral nervous system at the neuromuscular junctions and spreads to the CNS, where it replicates exclusively within the gray matter. It then passes centrifugally along autonomic nerves to reach other tissues, including the salivary glands, adrenal medulla, kidneys, and lungs. Passage into the salivary glands in animals facilitates further transmission of the disease by infected saliva. The neuropathology of rabies resembles that of other viral diseases of the CNS, with infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells into CNS tissue and nerve cell destruction. The pathognomonic lesion is the Negri body (Figure 17–4), an eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusion distributed throughout the brain, particularly in the hippocampus, cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and dorsal spinal ganglia.

FIGURE 17–3. Sequential steps (1-8) in the pathogenesis of rabies virus infection are shown in the diagram.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree