OUTLINE

Standards and Standard-Setting Agencies

General Principles for Weighing and Measuring

Recommended Weighing Procedures

Recommendations for Using Volumetric Devices

I. STANDARDS AND STANDARD-SETTING AGENCIES

A. Because balances, weights, and volumetric measuring devices are essential tools in the practice of pharmacy, pharmacists need to know how to select and properly use this equipment. In order to access, understand, and use the accepted standards for this equipment, it is necessary to know the organizations and agencies that have responsibility for these areas. In the United States, this is a complex affair. Unlike many other countries, in which authority for weights and measures is centralized in their federal governments, in the United States, this function is decentralized in a patchwork of state and federal agencies and not-for-profit organizations.

1. National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST): This agency, which was formerly called the National Bureau of Standards (NBS), is a nonregulatory agency in the Department of Commerce. It was established by Congress in 1901 to “serve as a national scientific laboratory in the physical sciences, and to provide fundamental measurement standards for science and industry” (1). It is charged with working with the states to develop laws, codes, and procedures to secure uniformity of weights and measures and methods of inspection. Since 1949, NIST has published the guidebook known as Handbook 44. This book contains specifications, tolerances, and other technical requirements for weighing and measuring devices for everything from livestock scales to taximeters to jewelry scales, and it includes standards for prescription balances and volumetric devices used in pharmacies (1). Internet site: www.nist.gov.

2. National Conference on Weights and Measures (NCWM): Though it is not a government agency, the NCWM works with the Office of Weights and Measures of NIST in creating weights and measures standards. The standards in Handbook 44 are reviewed, revised, amended, and adopted each year at the Annual Meeting of the NCWM (1). Also, in cooperation with the NIST, state government weights and measures officials, and private sector individuals, the NCWM operates the National Type Evaluation Program (NTEP) to evaluate and certify weighing and measuring devices such as electronic balances (2). Internet site: www.ncwm.net.

3. American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM): Now called ASTM International, this not-forprofit organization develops and publishes voluntary standards for materials, products, systems, and services. The “Standard Specifications for Laboratory Weights and Precision Mass Standards” (E 617 – 97), which specifies our classes of weights, is a publication of ASTM. Internet site: www.astm.org.

4. American National Standards Institute (ANSI): This is also a not-for-profit, nongovernmental organization. It does not develop standards, but it serves as the U.S. representative to international standard-setting organizations, such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ANSI also accredits national organizations, such as ASTM, that develop standards. Internet site: www.ansi.org.

5. United States Pharmacopeial Convention (USP): Since 1820, USP, another not-for-profit, nongovernmental organization, has been setting standards for drugs and medications in the United States. USP publishes the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) and the National Formulary (NF), two separate compendia that are now published in a combined volume that is commonly referred to simply as the USP. This book of standards contains drug and dosage form monographs that specify the standards for strength, quality, and purity for each monograph entity. USP also contains general chapters that describe tests, assays, and practice standards for drug manufacturing and compounding. USP Chapter 〈1176〉 Prescription Balances and Volumetric Apparatus sets standards for weighing and measuring equipment used in pharmacies (3). Internet site: www.usp.org.

B. With this information in mind, it is important to remember the following:

1. Standards, such as those in Handbook 44, ASTM E 617–97, or USP, have been developed by government or private agencies for use by the state and federal governments in regulating commerce and protecting public health and safety. Though they are written as voluntary standards, they become legally enforceable if they are written into federal laws (such as the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act) or state statutes or administrative codes.

2. Because requirements for weighing and measuring equipment in pharmacies are primarily regulated by state statutes, it is important for pharmacists to be informed about the applicable state codes for pharmacy equipment for their practice sites. For example, if a state statute states that pharmacies must use graduates that conform to the standards in Handbook 44, the graduate specifications in that document would be legally enforceable in the pharmacies of that state.

3. Even when nationally recognized standards are not codified in state statutes and federal laws, these standards provide invaluable guidance to pharmacists in selecting and using appropriate weighing and measuring equipment and apparatus.

II. GENERAL PRINCIPLES FOR WEIGHING AND MEASURING

To prepare accurate dosage forms, the pharmacist and pharmacy technician must use weighing and measuring apparatus with care and understanding and must be conscious of the following general principles:

A. Select weighing equipment and measuring devices appropriate for the intended purpose.

B. Use the devices and operate the equipment with recommended techniques that ensure accuracy of measurement.

C. Maintain the equipment so that it is clean and free of chemical contamination and retains the prescribed tolerances.

III. BALANCES AND WEIGHTS

A. Definitions: In selecting a balance for purchase or for use in compounding, the pharmacist and pharmacy technician need to be familiar with the following terms:

1. Capacity: the maximum weight, including containers and tares, that can be placed on a balance pan

2. Sensitivity: also referred to as Sensitivity Requirement or Sensitivity Reciprocal, the smallest weight that gives a perceptible change in the indicating element (e.g., one subdivision deflection of the indicator pointer on the index plate of a double-pan balance; one number change on the digital display of an electronic balance)

3. Readability: for electronic balances, the smallest weight increment that can be read on the digital display of the balance (e.g., 0.001 g). On a double-pan balance, the smallest weight increment is determined by the value of a hash-mark on the graduated dial or weighbeam (e.g., on the metric scale of the dial, each mark stands for 0.01 g, and on the apothecaries’ scale of the dial, each mark stands for 0.2 grains).

4. Precision: the reproducibility of the weighing measurement as expressed by a standard deviation. A similar term, repeatability, is sometimes used in specifications for electronic balances.

5. Accuracy: the closeness of the displayed weight, as measured by the balance, to the true weight, as known by the use of a calibration weight or weights

B. Prescription balances

There are two types of balances used for prescription compounding: double-pan torsion balances and single-pan electronic balances.

1. Double-pan torsion balances

DOUBLE-PAN TORSION BALANCE

a. Specifications for prescription balances are given in Section 2.20 Scales in Handbook 44. In general, these balances meet the specifications for NIST Class III scales (formerly designated Class A); however, Handbook 44 gives some design elements and tolerance specifications that are specific for prescription balances (1).

b. USP Chapter 〈1176〉 specifies that a Class A (that is, Class III) prescription balance be used for all weighing operations required in prescription compounding (3). (However, see 2.a., which follows, concerning allowance for balances giving equivalent or better accuracy.)

c. Sensitivity:These balances meet or exceed a sensitivity requirement of 6 mg with no load and with a load of 10 g on each pan (1,3).

d. Capacity:The maximum load capacity should be stated in the manufacturer’s specifications for that particular balance. Though a balance may have a capacity such as 60 or 120 g, it is usually impractical to weigh amounts >15 to 30 g on a double-pan balance because the volume occupied by larger weights of most powders and dry ingredients is difficult to contain on weighing papers, boats, or dishes without spilling.

e. Because Handbook 44 is written to describe nearly all types of weighing devices, it is a rather extensive document and is written in technical language. Therefore, for the pharmacist selecting a torsion prescription balance, the most practical procedure is to buy a balance that is certified to meet or exceed the specifications for a NIST Class III prescription balance.

2. Electronic single-pan balances

a. Though the USP Chapter 〈1176〉 specifies that Class A (now Class III) prescription balances be used for all weighing operations required in prescription compounding, a note at the beginning of that chapter states that other balances may be used, provided they give equivalent or better accuracy (3).

b. Sensitivity: It is important to pick an electronic balance that has a sensitivity that is at least equivalent to the 6-mg standard for Class III prescription balances. Electronic, single-pan balances with readability and repeatability of 1 mg are available, and these would exceed this Class III balance sensitivity specification.

c. Capacity: Capacities vary with the brand, model, and price. Often as the capacity goes up, the sensitivity or readability goes down. Some electronic balances come with dual modes:

ELECTRONIC BALANCE

one mode for low capacity and high sensitivity and a second mode with larger capacity but lower sensitivity. When using such a balance, it is important to be operating in the proper mode for the weighing task.

d. Electronic balances with an official NTEP rating have been tested and evaluated by the NCWM and are certified to meet applicable U.S. weight and measure standards (2).

e. Most individuals who have used electronic balances find them easier to use and more accurate than a traditional double-pan torsion balance. Though appropriately selected electronic balances meet or exceed the requirements for prescription balances as stated in Handbook 44 and the USP, before purchasing an electronic balance, the pharmacist should consult with his or her state board of pharmacy to determine whether a given balance meets the applicable state statutes or codes for pharmacy equipment.

3. Minimum or least weighable quantity.

It is extremely important to distinguish between the minimum quantity that is possible to detect or weigh on a balance (i.e., the balance’s sensitivity) and the minimum quantity that may be weighed if you wish to ensure a desired level of accuracy. The least or minimum weighable quantity (MWQ) allowed for prescription compounding is 20 times the sensitivity or sensitivity requirement as illustrated here.

a. A maximum 5% error is the generally accepted standard for weighing operations used in compounding (3).

b. To avoid errors of 5% or more when weighing on a balance, calculate the MWQ by equating 5% × MWQ with the sensitivity requirement (SR) of the balance. This is because that balance cannot detect differences in weight smaller than the SR; therefore, any smaller amounts could be in error. The general equation is:

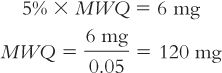

For example, on a Class III balance with a measured sensitivity requirement of 6 mg, the MWQ is calculated to be 120 mg:

c. A more sensitive balance could obviously use a smaller MWQ. For example, a balance with a sensitivity requirement of 1 mg would have a MWQ of 20 mg (checking by percent: 5% × 20 mg = 1 mg).

d. If an amount of drug or chemical is needed that is less than the MWQ determined for that balance, an aliquot method of measurement should be used. Methods of calculating aliquot amounts are presented in Chapter 10, Aliquot Calculations.

4. Balance testing

a. USP general guidelines

(1) Chapter 〈1176〉 states, “All balances should be calibrated and tested frequently using appropriate test weights, both singly and in combination” (3).

(2) Chapter 〈795〉 Pharmaceutical Compounding—Nonsterile states, “Equipment and accessories used in compounding are to be inspected, maintained, cleaned, and validated at appropriate intervals to ensure the accuracy and reliability of their performance” (4).

b. Frequency of testing: As can be seen from the foregoing statements, the frequency of balance testing is not explicitly stated and is therefore a matter of professional judgment and experience with a particular balance and practice patterns with that instrument. It is important to have a written plan for scheduled frequency of testing.

c. Records of testing:A balance-testing record should be maintained by the pharmacy; the record should include the date, the type of testing and calibration procedures performed, the results, and the name or initials of the person who performed the procedures. A sample standard operating procedure (SOP) for testing a Class III torsion balance is given in Chapter 12 Figure 12.3, and a sample testing record sheet used in conjunction with the SOP is shown in Figure 14.1.

d. Testing procedures for electronic balances

(1) Testing and calibration procedures for electronic balances are given in the use and maintenance manual provided by the balance manufacturer.

(2) The usual procedure involves the use of special test calibration weights that may be provided with the balance or purchased separately. Usually ASTM Class 1 (NBS Class S) weights are required.

e. Testing procedures for Class III torsion balances

(1) Test weights:ASTM Class 4 (NBS Class P) or better weights are recommended for testing Class III prescription balances. This weight set should be reserved for testing the balance and for checking weights that are routinely used for compounding (3). The graduated dial or rider on a double-pan torsion balance may not be used to calibrate the balance because an internal mechanism does not constitute a valid standard for testing an instrument.

(2) USP Chapter 〈1176〉 specifies the following tests to be performed on torsion prescription balances. As stated earlier, a sample testing procedure with the details of these tests is shown in Figure 14.1.

(a) Sensitivity requirement

(b) Arm ratio test

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree