Were objectives of this research initiative specified in general and more specific terms as well?

Let us remember that a distinction should be made between general objectives, that is, points in the larger frame of efforts to solve the problem of which the study is a part and specific goals to be reached by the study itself.

Was the research hypothesis explicit enough allowing its acceptance or rejection in view of the present study?

The research hypothesis is a proposition to be accepted or rejected by the study itself. Hypothesis components are based on operational and measurable definitions and accompanied by clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, wherever possible and needed. The hypothesis is discussed in the context of such rules.

What are the elements of the research question that require discussion in terms of research methodology, data collection, data analysis, presentation and evaluation of findings? What are their strengths and weaknesses?

In the study of cause–effect relationships, useful components of a research question include (target) population such as the type of patients, intervention such as treatment, surgery or any other type of care or prevention, control group(s) if comparisons are involved, outcome(s) of treatment or care such as survival, changes in the severity of disease, occurrence of adverse effects and alike, time frame for the treatment intervention itself and period of time over which outcomes are studied, as well as setting, that is, clinical environment with its practices, institutional habits, culture and rules in which the health problem under study evolves. The acronym PCICOST (population, condition of interest, intervention, controls, outcomes, setting, time-frame) summarises the research question components and makes them more specific with regard to the space, time and individuals concerned. If the study is not etiological in nature, other types of research questions are used.

If the study is focused on a cause–effect relationship like a clinical trial on the effectiveness of a procedure or an observational analytical study on the adverse effects of drugs or other medical interventions, what are the causal criteria that were confirmed, understood better or rejected by the study?

What is the main contribution of this study as seen by the authors themselves?

What is missing and what should be done next?

In this spirit, the ‘discussion’ section is perhaps intellectually the most challenging part of any research study. The other challenge is identifying the problem initially.

Hence, the ‘discussion’ section should further clarify objectives, hypothesis, research question and answers brought forward by the research study. It is meaningful mostly if it is conducted in light of stated research objectives, hypothesis and question. Several chapters in this book examine in more details these cornerstones of any research initiative.

What should a discussion section NOT be? It should not be a repository or dumping ground or patchwork of any information that does not fit in the ‘introduction’, ‘material and methods’ or ‘results’ sections of a medical article. When the author of this chapter was writing his first research paper a long time ago, he was told : ‘… You don’t know where to put this information? Put it in the ‘discussion’, of course!…’ This is no longer acceptable.

Formally, the ‘discussion’ section of any research report is an exercise in informal logic and argumentation. It must be seen, understood and written in this general spirit.

Informal Logic and Critical Thinking in a Medical Article

Discussing medical articles in the context of logic and thinking first requires some basic definitions of these terms.2,3 By informal logic, we mean the evaluation of reasoning as it happens in natural language used in everyday life. Informal logic is an important part of critical thinking which itself is reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe and/or do. An argument means a set of statements (propositions) offered as reasons for another statement, a conclusion. Argumentation then is a process of discussing and advancing arguments: proposing, defining, explaining and valuing considerations (statements, propositions, premises) designed to support and justify some claim (conclusion). Equipped with those definitions, how can we understand medical articles?

Critical thinking today takes into account not only classical ways of reasoning (Aristotelian categorical syllogisms or ancient Nyaya Indian school of argumentation) but also enriches them tremendously through Toulmin’s modern argument and argumentation.4,5 It is now offered for consideration and applications in medicine.2,3 Argumentation as a vehicle of critical thinking is now seen in a framework of the abovementioned basic vocabulary as a process of making assertions (claims) and providing support and justification for these claims using data, facts and evidence.4–6 A medical article is the embodiment of such a process.

IMRAD Medical Article

The Introduction—(Material and) Methods—Results—And—Discussion (cum conclusions) format is used not only in medical writing but in other sciences as well. Its structured message is now enhanced by an equally structured abstract7 and better-defined research question(s).7,8

The IMRAD contains in its sections answers to the following important questions9,10:

This chapter is about the last point mentioned above, that is, the Discussion.

Within the IMRAD format, the author must present all necessary evidence and elements of an argument to explain to the reader what are the strengths and weaknesses of conclusions as a final product of an argumentation path.

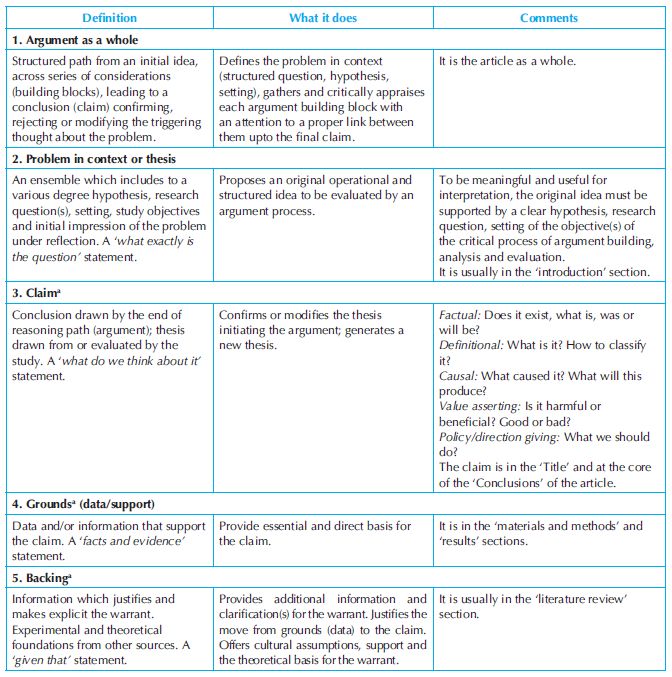

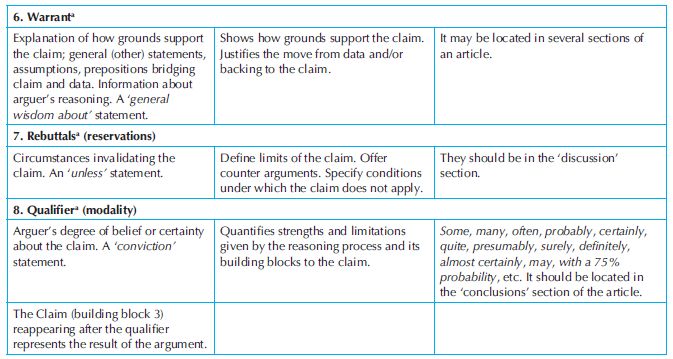

The modern argument proposed by Toulmin4 in the 1950s consists of a reasoning path from first-hand evidence (grounds) to an ensuing claim, a resulting proposal and statement. It links six components or ‘building blocks’ that have been defined, explained and commented upon in Table 27.1.

Adapted from Jenicek, 2006.1

aToulmin’s argument components.4

Such essential building blocks already exist, but are somehow ‘hidden’ in various medical articles. As might be expected, thesis may be found in the ‘Introduction’, grounds in ‘materials and methods’ and ‘results’ sections, backing and warrant in the ‘Review of the literature’ and ‘Discussion’, rebuttals in ‘Discussion’ as well and claim often appears in the ‘Title’ itself and ‘Conclusions’ of the article.1 Table 27.1, therefore, presents an overview of Toulmin’s original argument building blocks (‘organs within a living system of argument’ as he calls them) and indicates a possible location of these building blocks in a medical article. While reading the literature, we may quickly notice that there is no formal rule where they should be found. Usually, they are scattered in bits and pieces across the IMRAD sections. However, it is worthy to review them in an organised and systematic way in the ‘discussion’ section of a medical article. Statements in natural language, listed in italics below (Adapted from Jenicek1), are and should be supported by argument building blocks. Consider to state, explain and support the following:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree