Figure 30.1. General flow of manuscripts in peer-reviewed journals. Grey boxes represent actions by authors and green boxes represent actions by the editor and/or publication manager.

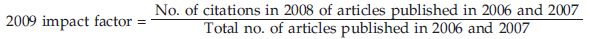

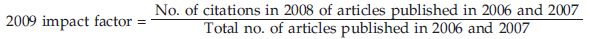

Therefore, if the journal published 100 articles in 2006 and 2007 (denominator), and those articles were cited 200 times in 2008 (numerator), the impact factor of the journal would be 200/100 = 2. In other words, every article published in 2006 and 2007 was, on average, cited twice in 2008 (average citations per document). The impact factor is the most commonly used measure of the quality of a journal (used by researchers to submit papers by librarians to manage subscriptions and by publishers as a marketing tool) and it is often used in assessing the quality of publications for awarding grants and academic positions/promotions. However, it must be borne in mind that the impact factor has many limitations and is by no means a measure of the quality of a particular paper or researcher.

3. The journal should be indexed on major biomedical databases (e.g. MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE/Excerpta Medica) and readily accessible across the globe (available online, either as free content or as ‘pay-per-view’).

4. The target journal has a built-in readership (e.g. sponsoring society members).

5. The journal has access to good public relations services, as publication of research in these journals is often accompanied by press releases in the general media.

Type of Publication

1. General journals tend to have higher ISI impact factors than subspecialty journals. However, subspecialty journals are likely to have a more focused audience.

2. It is worthwhile to check the types of articles published in the target journal, that is, some journals do not publish case reports while others may not publish original research or review articles.

Editorial Office Standards and Efficiency

1. How is the journal funded and governed? Independently funded, subscription-based journals with an editorial board comprising recognised leaders in the field have more credibility with readers than privately funded journals without an editorial board.

2. Does the editorial office have a personal interface? In this age of online publishing, it is preferable to have a responsive ‘person’ who can be contacted to sort out any issues that may arise during the editorial processing of a manuscript, for example need for permission to reproduce a figure or a table.

3. Are the ‘instructions to authors’ accessible and clear? Different journals have different formatting requirements and it is essential to carefully read the specific ‘instructions to authors’ of the target journal before writing a paper.

4. Does the journal offer an electronic submission and tracking system? Although not essential, it is definitely useful for authors to be able to track the progress of their manuscript through the publication process using an online system.

5. Does the target journal use referees with established expertise? The editorial board of the target journal gives some idea of the type of expertise available to the journal. In addition, it is helpful to check the last issues of the journal from previous years to become familiar with the quality of peer reviewers used by the target journal.

6. Have colleagues received helpful and constructive criticism from the editorial office in the past? The quality of feedback received from peer reviewers is extremely important in revising and refining the manuscript, and the past experience of colleagues working in your area can be a useful measure of the journal’s calibre.

7. What time frames does the journal follow, that is, what are the delays between submission and initial decision and between acceptance and publication? Most top-tier journals receive a huge volume of content and there can often be a delay of between 3 and 7 months between submission and publication. Sometimes, researchers may opt for a lower tier journal that offers quicker publication over waiting for a longer period of time in a higher tier journal. Researchers should ascertain the time frames of target journals and balance the high profile of the higher impact factor journal with the urgency for publication. Of course, most established journals would provide an option to prioritise exceptional content. Some journals also offer ‘early online’ publication ahead of the print issue.

8. Does the target journal offer the option of ‘fast tracking’ for publication? Occasionally, researchers may wish their work to be published ahead of or during an important meeting or congress, but not all journals may provide the option of ‘fast-track’ publication. Therefore, in some cases a lower tier journal with option for fast-track publication may be preferred over a higher tier journal that does not offer this option.

Cost

It is always advisable to confirm any submission fee, acceptance fee, per-page fee and whether there is a cost associated with the publication of colour figures when selecting a journal. Open access journals charge authors for publication and subscription-based journals generate revenue from subscriptions and ‘pay per view’ streams. Some publishers of subscription-based journals charge authors for the inclusion of coloured figures while others do not. Lastly, some publishers also charge for incorporating lengthy changes at the page proof stage. Therefore, researchers should do a thorough check of the target journal before submitting their work.

Principles for Choosing the most Appropriate Journal

1. Assess the content of the manuscript (basic science versus clinical and general versus specific). Look at previous issues of the intended journal and see what kinds of papers they publish. Does your paper fit the type of content the journal seems to prefer? Will the paper add to work they have already published?

2. Aim for the highest possible journal in terms of visibility and quality.

3. Balance the use of top-tier journals with the need for rapid publication in possibly lower tier journals.

4. Read instructions to authors and ensure they meet your requirements.

5. Look at recent issues of the journal and make sure you understand the journal style.

6. Consult your peers and mentors for advice.

Cover Letter

Many editors are experts in their fields, but they are not necessarily familiar with the entire breadth and depth of their speciality. Editors have a critical approach to the literature and are always open to reason. First and foremost, editors look for ‘novelty’ in the submitted biomedical research work. The cover letter should, therefore, clearly outline the novelty of the research.

For the purpose of scientific communications, novelty can be defined as follows:

- First report on the subject, that is, nothing similar exists at the time of submission.

- Research that provides definitive data in a previously reported subject, where controversy exists.

- Work that extends previous findings.

- Largest study of the research question.

The cover letter should also delineate the clinical or investigational relevance of the research. The most important/relevant research will have direct implications for management of disease, for example lead to a change in the treatment guidelines or alter current practice of treating a disease. A lesser degree of importance is attached to studies that develop or validate a method to establish a diagnosis or quantify severity of disease. These results are likely to mean that currently undertreated or untreated patients could qualify for treatment. A third level of relevance is attached to studies that establish mechanism of the disease or define prognosis, as these data can lead to the investigation of agents with new mechanisms of action and they help physicians in understanding the natural progression of the diseases. At the very least, the submitted work should be able to generate a hypothesis and stimulate interest in further testing of the research question.

The cover letter should also state that the submission represents original work that is not being considered for publication in any other journal, and that all the listed authors meet the authorship criteria used by the journal (most commonly, the criteria of the ICMJE in the Uniform Requirements for Submission to Biomedical Journals).

Peer Review

What Is Peer Review?

Peer review is the process of subjecting research or ideas, be they journal manuscripts or grant applications, to scrutiny by experts in the field. Peer-reviewed journals rely heavily on members of their honorary Editorial Boards (listed on the journal masthead) to provide expert feedback on submitted manuscripts. However, most journals also require the help of additional experts to assess the high volume of submissions and the contribution of these experts is often acknowledged in the last issue of the year or on the journal website. The peer-review process is coordinated by the journal’s editors or publication managers.

Common questions asked at the peer review stage (for submitted original research and review articles) are listed in the Appendix. In addition, there is often scope for ‘confidential comments to the editor’ and additional free text ‘comments to the author’.

Why Is Peer Review Important?

Peer review comments are used by journal editors to screen and select submitted manuscripts. The input from external experts ensures that the journal content is balanced and provides complete coverage of the relevant information (as opposed to selective/biased citation of favourable papers in a review article). For original research articles, peer review ensures that the study design is appropriate, the right statistical analyses have been used and that the conclusions are supported by the results.

The peer review process is critical to establishing a credible body of knowledge for others to build upon. Peer review gives a stamp of credibility to the contents of the manuscript because it assures readers that experts in the field have approved the contents. Manuscripts that have not been peer reviewed tend to be viewed with suspicion and a certain degree of scepticism.

Types of Peer Review