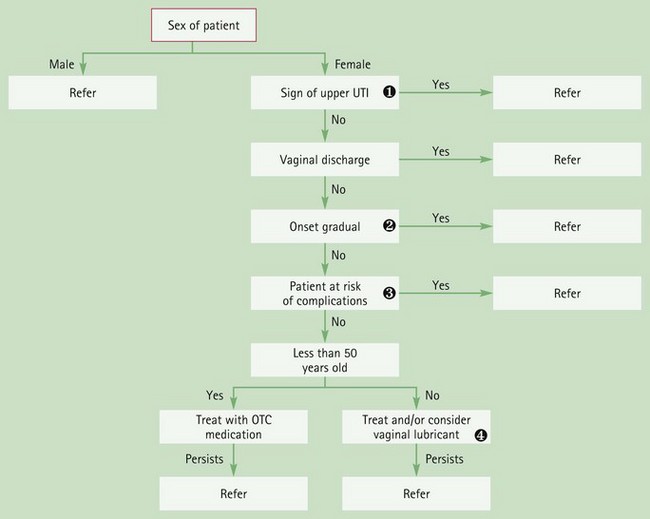

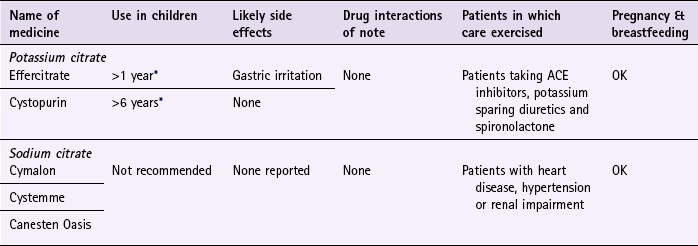

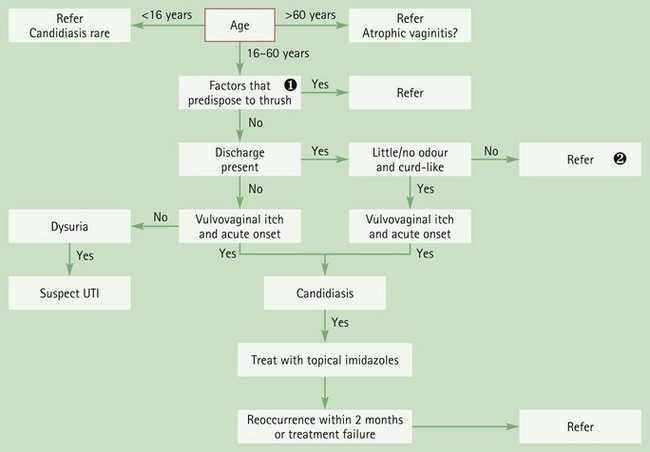

Chapter 5 Background Urinary tract infections (UTI) are one of most common infections treated in general medical practice and will affect up to 15% of women each year. Patients aged between 15 and 34 account for the majority of cases seen within a primary care setting and it is estimated that up to 50% of all women will experience at least one episode of cystitis in their lifetime; half of whom will have further attacks. Certain factors do increase the risk of a UTI: in young women, frequent or recent sexual activity and previous episodes of cystitis; the use of diaphragms or spermicidal agents; advancing age; and diabetes (can indicate poor diabetic control). Additionally, cystitis affects 1 to 4% of pregnant women (Le et al 2004). The majority of patients who present in the community pharmacy will have acute uncomplicated cystitis (Table 5.1). and accurately made a self-diagnosis. The pharmacist’s aims are therefore to confirm a patient self-diagnosis, rule out upper urinary tract infection (pyelonephritis) and identify patients who are at risk of complications as a result of cystitis. Asking symptom-specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine if referral is needed (Table 5.2). Table 5.1 Causes of cystitis symptoms and their relative incidence in community pharmacy Specific questions to ask the patient: Cystitis Pyelonephritis: The most frequent complication of cystitis is when the invading pathogen involves the ureter or kidney by ascending from the bladder to these higher anatomical structures. The patient will show signs of systemic infection such as fever, chills, flank or loin pain and possibly nausea and vomiting. Referral is needed to confirm the diagnosis, exclude pelvic inflammatory disease and issue appropriate treatment (7-day course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily). Sexually transmitted diseases: Sexually transmitted diseases can be caused by a number of pathogens, for example Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoea. Symptoms are similar to acute uncomplicated cystitis but they tend to be more gradual in onset and last for a longer period of time. In addition pyuria (pus in the urine) is usually present. Oestrogen deficiency (atrophic vaginitis): Postmenopausal women experience thinning of the endometrial lining as a result of a reduction in the levels of circulating oestrogen in the blood. This increases the likelihood of irritation or trauma leading to cystitis symptoms. If the symptoms are caused by intercourse, symptomatic relief can be gained with a lubricating product. Referral for possible topical oestrogen therapy would be appropriate if the symptoms recur. Medicine induced cystitis: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs; especially tiaprofenic acid), allopurinol, danazol and cyclophosphamide have been shown to cause cystitis. Vaginitis: Vaginitis exhibits similar symptoms to cystitis, in that dysuria, nocturia, and frequency are common. It can be caused by direct irritation (e.g. use of vaginal sprays and toiletries) All patients should be questioned about an associated vaginal discharge. The presence of vaginal discharge is highly suggestive of vaginitis and referral is needed. Figure 5.1 will aid the differentiation of cystitis from other conditions. Current OTC treatment is limited to products that contain alkalinising agents, namely sodium citrate, sodium bicarbonate and potassium citrate. (Applications to reclassify trimethoprim and nitrofurantoin in the UK have been made but were withdrawn due to pressure from medical groups.) Alkalinising agents are used to return the urine pH back to normal thus relieving symptoms of dysuria. However, they have dubious efficacy with little trial data to support their use. Only one trial by Spooner (1984) could be found to support their efficacy. Spooner concluded that, when treated with a 2-day course of Cymalon, 80% of patients with cystitis for whom there was no clear clinical evidence of bacterial infection did gain symptomatic relief. Cranberry juice is a popular alternative remedy to treat and prevent urinary tract infections, although few clinical trials have been performed to substantiate or refute its clinical effectiveness. A Cochrane review (Jepson & Craig 2012) identified 10 studies comparing cranberry juice or cranberry tablets to placebo. The review found cranberry products significantly reduced the incidence of UTIs at 12 months, particularly in women who suffer recurrent infections. However, drop out rates in the trials were high suggesting many patients may not be able to tolerate cranberry juice long term. The authors concluded that there was evidence that cranberry juice did offer some protection against recurrence of urinary tract infections in women that suffer symptomatic UTIs. However, it is still unclear what amount and concentration needs to be consumed, nor how long patients should take it for. Prescribing information relating to cystitis medicines reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 5.3 and useful tips relating to patients presenting with cystitis are given in Hints and Tips Box 5.1. Practical prescribing: Summary of medicines for cystitis ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme. *Children should not be treated for UTI by pharmacists as unusual in this age group. Jepson, RG, Williams, G, Craig, JC. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 10):2012. [Art. No.: CD001321. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001321.pub5]. Jepson, RG, Mihaljevic, L, Craig, JC. Cranberries for treating urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):1998. [Art. No.: CD001322. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001322]. Le, J, Briggs, GG, McKeown, A, et al. Urinary tract infections during pregnancy. An Pharmacother. 2004;38(10):1692–1701. Spooner, JB. Alkalinisation in the management of cystitis. J Int Med Res. 1984;12:30–34. Vaginal discharge Patients of any age can experience vaginal discharge. The three most common causes of vaginal discharge are bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis (thrush) and trichomoniasis (Table 5.4). As thrush is the only condition that can be treated OTC, the text concentrates on differentiating this from other conditions. Table 5.4 Causes of vaginal discharge and their relative incidence in community pharmacy Many patients will present with a self-diagnosis and the pharmacists’ role will often be to confirm a self-diagnosis of thrush. This is very important as studies have shown that misdiagnosis by patients is common (Ferris et al 2002) and can have important consequences because other conditions can lead to greater health concerns. For example, bacterial vaginosis has been linked with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and the preterm delivery of low-birth-weight infants and C. trachomatis can cause infertility. Symptoms of pruritus, burning and discharge are possible in all three common causes of vaginal discharge. Therefore no one symptom can be relied upon with 100% certainty to differentiate between thrush, bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis. However, certain symptom clusters are strongly suggestive of a particular diagnosis. Asking symptom specific questions will help the pharmacist to determine if referral is needed (Table 5.5). Specific questions to ask the patient: Vaginal discharge Trichomoniasis: Trichomoniasis, a protozoan infection is primarily transmitted through sexual intercourse. It is uncommon compared to bacterial vaginosis and thrush. Up to 50% of patients are asymptomatic. If symptoms are experienced a profuse, frothy, greenish-yellow and malodorous discharge accompanied by vulvar itching is typical. Other symptoms can include vaginal spotting, dysuria and urgency. Referral for metronidazole (400 mg bd for 5 to 7 days) is required. Cystitis: Dysuria can affect up to one in three women with vaginal infection. However, the patient will often be able to sense that it is an external discomfort, rather than an internal discomfort located in the urethra or bladder that occurs with urinary tract infections. Figure 5.2 will help in the differentiation of vaginal thrush from other conditions in which vaginal discharge is a major presenting complaint. Fig. 5.2 Primer for differential diagnosis of vaginal thrush. Imidazoles and triazoles have proven and comparable efficacy with clinical cure rates between 85 and 90%. Additionally, cure rates between single or multiple dose therapy and multiple day therapy show no differences (Nurbhai et al 2007, updated in 2009). Treatment choice will therefore be driven by patient acceptability and cost.

Women’s health

Cystitis

Prevalence and epidemiology

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Incidence

Cause

Most likely

Acute uncomplicated cystitis

Likely

Pyelonephritis

Unlikely

Sexually transmitted disease, oestrogen deficiency

Very unlikely

Medicine induced cystitis, vaginitis

![]() Table 5.2

Table 5.2

Question

Relevance

Duration

Symptoms that have lasted longer than 5 to 7 days should be referred because of the risk that the person might have developed pyelonephritis

Age of the patient

Cystitis is unusual in children and should be viewed with caution. This might be a sign of a structural urinary tract abnormality. Referral is needed

Elderly female patients (>70 years) have a higher rate of complications associated with cystitis and are therefore best referred

Presence of fever

Referral is needed if the person presents with fever associated with dysuria, frequency and urgency, as fever is a sensitive indicator of an upper urinary tract infection

Vaginal discharge

If a patient reports vaginal discharge then the likely diagnosis is not cystitis but a vaginal infection

Location of pain

Pain experienced in the loin area suggests an upper urinary tract infection

Conditions to eliminate

Unlikely causes

Very unlikely causes

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Cranberry juice

Practical prescribing and product selection

![]() Table 5.3

Table 5.3

References

Background

Incidence

Cause

Most likely

Bacterial vaginosis

Likely

Thrush, (medicine-induced thrush)

Unlikely

Trichomoniasis, atrophic vaginitis, cystitis

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

![]() Table 5.5

Table 5.5

Question

Relevance

Discharge

Any discharge with a strong odour should be referred. Bacterial vaginosis is associated with a white discharge that has a strong fishy odour and trichomoniasis is malodorous with a green-yellow discharge. By contrast, discharge associated with thrush is often described as ‘curd-like’ or ‘cottage cheese-like’ with little or no odour

Age

Thrush can occur in any age group, unlike bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis, which are rare in premenarchal girls. In addition, trichomoniasis is also rare in women aged over 60

Pruritus

Vaginal itching tends to be most prominent in thrush compared with bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis where itch is slight

Onset

In thrush, the onset of symptoms is sudden, whereas bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis onset tends to be less sudden

Conditions to eliminate

Unlikely causes

Recurrent thrush (four or more episodes per year)

![]() If the person is pregnant or has diabetes then referral is the most appropriate option. If the person is suffering from medicine-induced candidiasis the prescriber should be contacted to discuss suitable treatment options and, if appropriate, alternative therapy.

If the person is pregnant or has diabetes then referral is the most appropriate option. If the person is suffering from medicine-induced candidiasis the prescriber should be contacted to discuss suitable treatment options and, if appropriate, alternative therapy.![]() Discharge that has a strong odour and is not white and curd-like should be referred, as trichomoniasis or bacterial vaginosis are more likely causes.

Discharge that has a strong odour and is not white and curd-like should be referred, as trichomoniasis or bacterial vaginosis are more likely causes.

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Women’s health