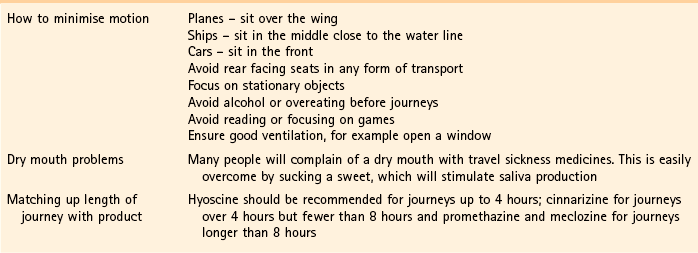

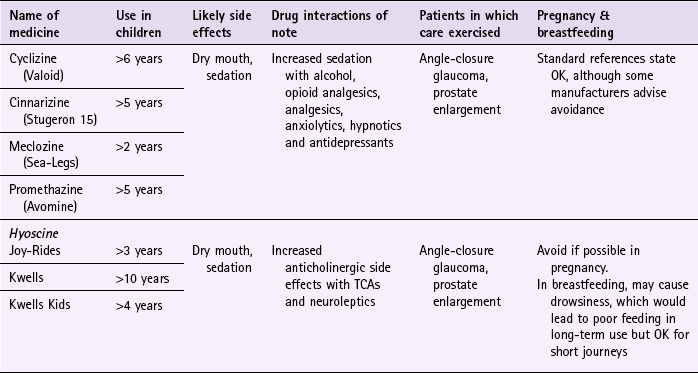

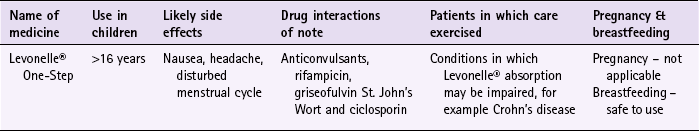

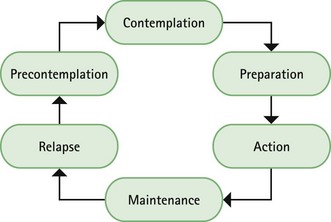

Chapter 10 Background First generation antihistamines (cyclizine, cinnarizine, meclozine and promethazine) and anticholinergics (hyoscine and scopolamine) are routinely recommended to prevent motion sickness. All have shown various degrees of effectiveness. A Cochrane review of scopolamine identified 14 studies (n = 1025) and found scopolamine to be superior to placebo and some other treatments (metoclopramide), and as good as antihistamines (Spinks et al 2011). Ginger has long been advocated for use as an anti-emetic. A review by Chrubasik and colleagues (2005) identified four exploratory studies of ginger in the prevention of motion sickness. The results of these studies suggested ginger was better than placebo, and similar in efficacy to other pharmacological agents. However, the studies were often in small numbers of patients, and of uncertain quality; the authors of the review concluded that further studies are required to confirm the effectiveness of ginger for motion sickness. Non-pharmacological approaches to the prevention of motion sickness using acupressure are also available OTC. Bruce et al (1990) investigated the use of Sea Band acupressure bands versus hyoscine and placebo. Eighteen healthy volunteers were subjected to simulated conditions to induce motion sickness. The findings showed that whilst hyoscine exerted a preventative effect, Sea Bands were no more effective than placebo. Further trials have confirmed these findings, although 1 small trial by Stern et al (2001) reported positive findings. However, accurate placement of the Sea Band seems to be important, and further trials are needed as acupressure has shown positive effects for nausea and vomiting associated with pregnancy. Prescribing information relating to medicines for motion sickness reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 10.1. They are most effective when given prior to exposure and products should be selected based on matching the length of the journey with the duration of action of each medicine (see Hints and Tips Box 10.1). Antihistamines used in products for motion sickness are first generation H1 antagonists and are associated with sedation. They therefore have the same side effects, interactions and precautions in use as other first generation antihistamines used in cough and cold remedies. For further information see page 8. Joy-Rides: Joy rides can be given from age 3 upwards. Children aged between 3 and 4 years should take half a tablet (75 µg) and no more than 1 tablet (150 µg) in 24 hours. Children between the age of 4 and 7 should take one tablet (150 µg) with a maximum of 2 tablets (300 µg) in 24 hours and children aged between 7 and 12 should take one to two tablets. Kwells: Kwells can only be given to children aged 10 and over. Children over 10 should take Kwells Kids: Kwells Kids contain half the amount of hyoscine (150 µg) than Kwells and are marketed at children under the age of 10, although older children can take them. Children aged between 4 and 10 should take half to one tablet. Like Kwells, the dose can be repeated every 6 hours when needed and be taken 30 minutes before travel. Bruce, DG, Golding, JF, Hockenhull, N, et al. Acupressure and motion sickness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1990;61:361–365. Chrubasik, S, Pittler, M, Roufogalis, B. Zingiberis rhizoma: a comprehensive review on the ginger effect and efficacy profiles. Phytomedicine. 2005;12:684–701. Spinks, A, Wasiak, J. Scopolamine (hyoscine) for preventing and treating motion sickness. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011. [Issue 6. Art. No.: CD002851. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002851.pub4]. Stern, RM, Jokerst, MD, Muth, ER, et al. Acupressure relieves the symptoms of motion sickness and reduces abnormal gastric activity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2001;7:91–94. Dahl, E, Offer-Ohlsen, D, Lillevold, PE, et al. Transdermal scopolamine, oral meclizine and placebo in motion sickness. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984;36:116–120. Klocker, N, Hanschke, W, Toussaint, S, et al. Scopolamine nasal spray in motion sickness: a randomised, controlled and crossover study for the comparison of two scopolamine nasal sprays with oral dimenhydrinate and placebo. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2001;13:227–232. Pingree, BJ, Pethybridge, RJ. A comparison of the efficacy of cinnarizine with scopolamine in the treatment of seasickness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1994;65:597–605. Emergency hormonal contraception Some concerns have been raised about women abusing the EHC because of its greater accessibility. However, a review of international experience with pharmacy supply of EHC found only a small proportion of women use EHC repeatedly (6.8% using it twice in 6 months, and 4.1% using it three times) (Anderson & Blenkinsopp 2006). Further, the review found improved access of the EHC through pharmacies resulted in fewer visits to Accident and Emergency, and did not result in increased transmission of sexually transmitted diseases or risky sexual behaviours. Prescribing information relating to EHC is discussed and summarised in Table 10.2. • First, has the patient had unprotected sex, contraceptive failure or missed taking contraceptive pills in the last 72 hours? EHC can only be given to patients who present within 72 hours. If more than 72 hours have elapsed but less than 120 hours (5 days) then the patient can have an intrauterine device fitted or be prescribed ulipristal. • Is the patient already pregnant? Details about the patient’s last period should be sought. Is the period late, and if so how many days late? Was the nature of the period different or unusual. If pregnancy is suspected a pregnancy test could be offered. • What method of contraception is normally used? Patients who take combined oral contraceptives might not need EHC. Guidelines from the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (2011) state: 1998. Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Lancet. 1998;352:428–433. Piaggio, G, von Hertzen, H, Grimes, DA, et al. Timing of emergency contraception with levonorgestrel or the Yuzpe regimen. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Lancet. 1999;353:721. Nicotine replacement therapy Recent legislation changes to ban smoking in public places (the first country was the Republic of Ireland in 2004, and others now include England, Scotland, Finland, Italy, Australia, New Zealand, Norway, France and Malta) has been championed as having potential positive impact on smoking rates; for example, by decreasing exposure to passive smoking and increasing quit rates. To establish any effect will take time but statistical data from Ireland has shown a fall in cigarette sales and surveys in Italy show a decrease in tobacco consumption. A study in England that compared smoking prevalence a year after legislation was passed (2007) found no significant difference in the level of smoking (http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications/003_Health_Lifestyles/Statistics%20on%20Smoking%202011/Statistics_on_Smoking_2011.pdf; accessed 22 November 2012). • tar-based products, which have carcinogenic properties • carbon monoxide, which reduces the oxygen-carrying capacity of the red blood cells • nicotine, which produces dependence by activation of dopaminergic systems. Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) has established itself as an effective treatment option. A 2008 Cochrane review (Stead et al 2008) found 111 trials (n > 40 000) comparing NRT to placebo or non-NRT treatments, and the results indicated that NRT increases rates of quitting smoking by 50-70%. It is not possible to say if one delivery system is better than another because comparative trials between delivery systems have not been conducted. Personal choice will therefore be the determining factor in which is chosen as being most suitable. In addition, the effectiveness of NRT is also affected by the level of additional support provided to the smoker and many smoking cessation services are offered through pharmacy as part of their contractual arrangements with local commissioners. Numerous intervention strategies have been used involving NRT. These include nurse-led services, workplace interventions, GP services and pharmacy-based services. A Cochrane review (Sinclair et al 2004) of pharmacy intervention assessed two trials that met the authors’ inclusion criteria. Findings suggested that trained community pharmacists, providing a counselling and record keeping support programme may have a positive effect on smoking cessation rates. A 2012 review, which included the Cochrane review, reported that there was good evidence that community pharmacists can deliver effective smoking cessation campaigns, and that structured interventions and counselling were better than opportunistic intervention (Brown et al 2012). Prescribing information relating to medicines for NRT reviewed in the section ‘Evidence base for over-the-counter medication’ is discussed and summarised in Table 10.3. Practical prescribing: Summary of medicines used as nicotine replacement therapy *Note: some formulations are only licensed for people over 18 years of age, for example Nicotinell and NiQuitin lozenges. Prior to instigation of any treatment it is important that the patient does want to stop smoking. Work has shown that motivation is a major determinant for successful smoking cessation and interventions based on the transtheoretical model of change put forward by Prochaska and colleagues have proved effective (Fig. 10.1). The model identifies six stages, progress through which is cyclical, and patients need varying types of support and advice at each stage. Gum: Nicorette gum is available as either fruit or mint flavours (unflavoured gum leaves a bitter taste in the mouth). The strength of gum used will depend on how many cigarettes are smoked each day. In general, if the patient smokes less than 20 then the 2 mg gum should be used. If more than 20 cigarettes per day, then the 4 mg strength may be needed. A maximum of 15 pieces of gum can be chewed in any 24-hour period. Inhalation cartridge: The inhalator can be particularly helpful to those smokers who still feel they need to continue the hand-to-mouth movement. Each cartridge is inserted into the inhalator and air is drawn into the mouth through the mouthpiece. Inhalators can be used to either reduce the number of cigarettes smoked or as part of a quit attempt. For the 10 mg inhalator a maximum of 12 cartridges per day can be used. Each cartridge can be used for approximately four sessions, with each cartridge lasting approximately 20 minutes of intense use. For the 15 mg inhalator a maximum of six cartridges can be used. Each cartridge can be used for approximately eight 5-minute sessions, with each cartridge lasting approximately 40 minutes of intense use.

Specific product requests

Motion sickness

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Practical prescribing and product selection

Antihistamines

Hyoscine

to 1 tablet. For adults the dose is one tablet. The dose can be repeated every 6 hours when needed. Tablets should be taken 30 min before travel.

to 1 tablet. For adults the dose is one tablet. The dose can be repeated every 6 hours when needed. Tablets should be taken 30 min before travel.

References

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Practical prescribing and product selection

Assessing patient suitability

Prevalence and epidemiology

Aetiology

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Practical prescribing and product selection

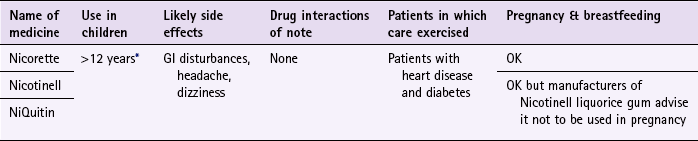

![]() Table 10.3

Table 10.3

Nicorette

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree