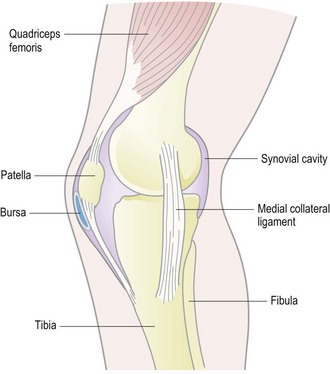

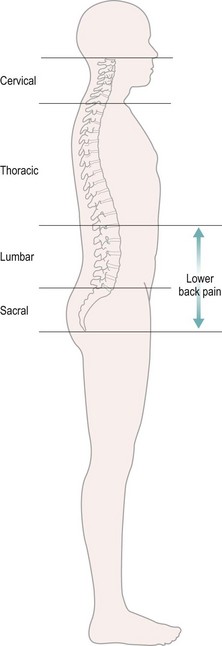

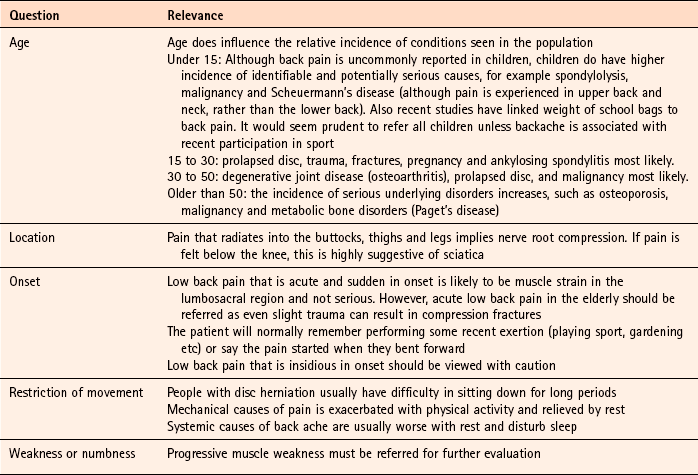

Chapter 8 Background • synovial joints: allow considerable movement (e.g. shoulder or knee) • fibrocartilaginous joints: are completely immoveable (e.g. the skull) or permit only limited motion (e.g. spinal vertebrae). Joints require additional stability and support. Strong bands of fibrous tissue known as ligaments bind together bones entering a joint to provide this additional support and stability. It is often the integrity of the connecting structures that are damaged in a musculoskeletal injury. The simplified diagram of the medial aspect of the knee joint in Fig. 8.1 illustrates the relationship of the connective structures to the skeleton and musculature. In the majority of cases an exact cause cannot be determined for the patient’s symptoms and is often referred to as simple, non-specific or uncomplicated low back pain. Pain originates from the lumbosacral region and is often mechanical in origin (Fig. 8.2) and includes problems caused by muscles, tendons, ligaments and discs. Contributory factors in the cause of low back pain are a general lack of fitness, occupational (as above) and psychosocial, for example anxiety and depression. Serious underlying pathology is very rare with infection and malignancy accounting for less than 1% of cases. The vast majority of patients (95%) who present in the pharmacy will have simple back pain that will, in time, resolve with conservative treatment. The remaining cases will have back pain with associated nerve root compression. It is extremely unlikely that a pharmacist will encounter a patient with serious spinal pathology, such as infection or malignancy. However, pharmacists should be mindful that age can affect the diagnosis. Table 8.1 highlights those conditions that can be encountered by community pharmacists and their relative incidence. Table 8.1 Causes of back pain and their relative incidence in community pharmacy Taking a thorough history is of key importance when evaluating a patient with low back pain. Begin questioning the patient with traditional questions regarding the pain: location, radiation, evidence of trauma, the effect pain has on mobility and factors which aggravate or relieve the pain. Asking a number of symptom-specific questions will aid differential diagnosis (Table 8.2). Sciatica: Sciatica typically occurs in the healthy middle-aged adult. Pain is acute in onset and radiates to the leg. Pain starts in the lower back and as it intensifies radiates into the lower extremity. Disc herniation usually involves those between L4 and L5 and L5–S1 vertebrae (Fig. 8.2), although most occur between L5 and S1. If disc herniation is minimal pain is characterised by being dull, deep and aching. It is usually felt in the upper part rather than the lower part of the leg and spreads from the lumbar spine. If the disc ruptures or herniates under strain then the pain is usually lancinating in quality, shooting down the leg like an electric shock. Valsalva movements, for example coughing, sneezing or straining at stool, often aggravate pain. Referral is needed for confirmation of the diagnosis. GPs can perform a straight-leg raising test whereby the pain of sciatica can be induced by elevating the leg of the patient when lying down. Prognosis is good, although improvement and recovery is often slower than in low back pain alone. Osteoarthritis: Patients in whom pain lasts longer than 12 weeks are said to suffer from chronic back pain. In the context of low back pain pharmacists should only manage acute problems; however patients will present with chronic symptoms and seek advice, especially on drug management. Degenerative joint disease is the most common cause of chronic low back pain in people older than fifty. It is associated with advancing age, and affects up to one-third of people aged over 65 and is twice as common in women. It can be localised to a single joint or involve multiple joints and most commonly affects the hands, knees, hips, neck, and low back. It is thought that an imbalance of synthesis and degradation of cartilage is responsible for the disease, which affects the whole joint. It is characterised by pain of insidious onset that progressively increases over months or years and is exacerbated by exertion and relieved by rest. Stiffness in the affected joint occurs typically in the morning and after prolonged rest but usually only lasts for 15 to 30 minutes. Infection (osteomyelitis): Symptoms of osteomyelitis include bone pain, general malaise and presence of high fever. There may be local swelling, redness and warmth at the site of the infection. Patients also usually exhibit a loss of range of motion to the affected body part. Ankylosing spondylitis: Spondylitis is characterised by thinning or loss of elasticity of the discs that cushion the vertebrae of the spine. It is three times more common in men and tends to run in families. Symptoms gradually worsen over a period of several months and experience periods of flare ups and remission. Patients commonly have marked stiffness on awakening and pain that alternates from side to side of the lumbar spine. Pain is worse at rest but improves with physical activity. Pain can be made worse by bending, lifting and prolonged sitting in one position (e.g. long car journeys). Up to 40% of patients may also show inflammation of the eye. Malignancy: Malignancy is very rare; it is more prevalent in patients over 50, although rates are still low – 0.14% in under 50 and 0.56% in patients over 50. A history of significant and unexplained weight loss, presence of anaemia, and failure of symptoms to improve over a 4-week period all warrant referral. Bed rest was once widely prescribed for patients with low back pain. However, systematic reviews have now proven that prolonged bed rest is counter-productive (Dahm et al 2010). The review found two trials (n = 401) that showed improvements in pain relief and functional status in patients with acute lower back pain (LBP) that were advised to stay active compared to bed rest. The authors conclude: Exercise programmes can help with acute back pain and have been shown to reduce recurrence. All systemic analgesics when prescribed as monotherapy have proven efficacy in pain relief at standard doses. However, the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for 7 to 10 days is widely advocated. A systematic review of NSAIDs in acute or chronic low back pain found treatment with an NSAID produced significant short-term improvement compared with placebo (Roelofs et al 2008). The review identified 65 trials, 28 of which were rated as ‘high quality’. The study failed to find any difference among the various NSAIDs. It also found that NSAIDs were no better than paracetamol for LBP. The authors did note that paracetamol had fewer side effects. Based on this observation, paracetamol may be the best first-line choice for most people. Patients must be advised to see their GP if symptoms fail to improve after 7 days. It has long been claimed that caffeine enhances analgesic efficacy and a number of proprietary products contain caffeine in doses ranging from 15 to 110 mg. A Cochrane review (Derry et al 2012) identified 19 studies (n = 7238), which involved mainly paracetamol or ibuprofen, with 100 to 130mg caffeine. Findings showed that there was a small but statistically significant benefit with caffeine used at doses of 100 mg or more, which was not dependent on the pain condition or type of analgesic. The authors concluded that the addition of caffeine (100 mg) to a standard dose of commonly used analgesics provides a small but important increase in the proportion of participants who experience a good level of pain relief. In light of this new data, if recommending caffeine-containing products, only those with 100 mg or more of caffeine should be given. Topical NSAIDs have been available OTC in the UK since ibuprofen was deregulated in 1988. Since then, a number of other NSAIDs have been deregulated from prescription only control. For NSAIDs to work they must penetrate the skin, be absorbed into tissues and be in sufficiently high concentration to inhibit COX enzymes. Experimental results suggest that NSAIDs do penetrate the skin but peak plasma concentrations are greatly lower than oral NSAIDs (approximately 5% of oral plasma levels). A recent systematic-review identified 47 studies comparing topical NSAIDs to placebo (Massey et al 2010). The review found topical NSAIDs to be significantly better than placebo, with achieving 50% pain relief with topical NSAIDs compared to 43% for placebo. The authors stated that there was insufficient data to reliably compare topical NSAIDs to each other, or to oral NSAIDs, but concluded that NSAIDs can provide good pain relief in acute musculoskeletal conditions, without the adverse events seen with oral NSAIDs. Rubefacients (also known as counter irritants) have been incorporated in topical formulations for decades. They cause vasodilation, producing a sensation of warmth that distracts the patient from experiencing pain. It has also been hypothesised that increased blood flow might help disperse chemical mediators of pain, although this in unsubstantiated. Numerous chemicals are listed as being rubefacients. Bandolier (http://www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/) have produced a detailed summary of topical analgesics, and within this document usefully reviewed what constituted a rubefacient. Their effect in controlling acute and chronic pain was reviewed by Matthews et al (2009). Seven studies (n = 697) for acute pain involved use of salicylates. Data showed there was no difference between topical salicylates and a topical placebo. A limited, but growing body of clinical evidence exists to assess whether complementary therapies are effective. In light of the growing public interest and the expanding volume of literature, four Cochrane reviews have been conducted on heat and cold therapy (French et al 2006), herbal remedies (Gagnier et al 2006), acupuncture (Furlan et al 2005) and massage (Furlan et al 2008) respectively. Herbal remedies: Several herbal medicines are promoted as treatments for various types of pain, some of which have been tested for the relief of symptoms of low back pain. A Cochrane review (Gagnier et al, 2006) reviewed three active constituents; Harpagophytum procumbens (Devil’s Claw), Salix alba (white willow bark), and Capsicum frutescens (cayenne). Devil’s Claw (standardised daily dose of 50 mg or 100 mg harpagoside) reduced pain more than placebo and a standardised daily dose of 60 mg was equally effective as 12.5 mg of rofecoxib (Vioxx, now withdrawn from the market). Similarly, Willow Bark (standardised daily dose of 120 mg and 240 mg of salicin) was also more effective than placebo and 240 mg of salicin was as effective as 12.5 mg of Vioxx. Cayenne (as a plaster) reduced pain more than placebo. It therefore appears that these products can be used as viable alternatives to conventional medicine.

Musculoskeletal conditions

General overview of musculoskeletal anatomy

Acute low back pain

Aetiology

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

Incidence

Cause

Most likely

Simple back pain (usually associated with physical activity)

Likely

Nerve root compression (e.g. sciatica), pregnancy, (osteoarthritis)

Unlikely

Osteomyelitis, ankylosing spondylitis

Very unlikely

Malignancy

Conditions to eliminate

Unlikely causes

Very unlikely causes

Evidence base for over-the-counter medication

Conservative treatment

Analgesics (paracetamol, aspirin, NSAIDs, e.g. ibuprofen, diclofenac)

Caffeine

Topical NSAIDs

Rubefacients

Complementary therapies

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree