Patient Story

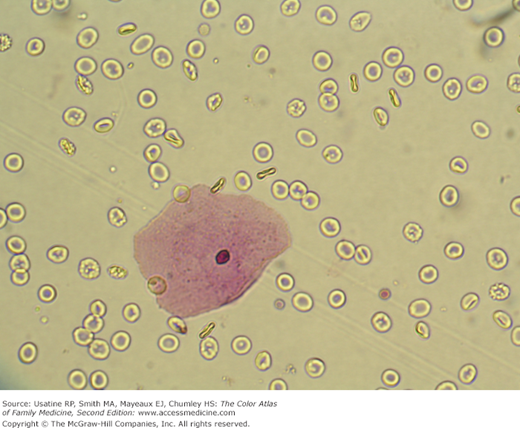

A 47-year-old woman presents to the office with severe right flank pain that does not radiate. Dipstick urinalysis shows hematuria, and microscopic examination confirms the presence of many red blood cells per high-power field (Figure 67-1). There is no pyuria or bacteriuria. The physician gives her some pain medication and sends her to get a CT urogram. The CT urogram shows a stone in the right ureter and some mild hydronephrosis. Fortunately for the patient, she passes the stone when urinating after the imaging study is complete.

Introduction

Examination of the urinary sediment is a test frequently done for evaluation of patients with suspected genetic/intrinsic (e.g., systemic lupus nephritis, renal sarcoidosis, sickle cell disease, glomerulonephritis, interstitial nephritis), anatomic (e.g., arteriovenous malformation), obstructive (e.g., kidney or bladder stones, benign prostatic hypertrophy), infectious, metabolic (e.g., coagulopathy), traumatic, or neoplastic disease of the urinary tract. Potential findings of red or white blood cells, casts, bacteria, or neoplastic cells help in directing further evaluation of a patient’s problem.

Epidemiology

- A finding of hematuria (2 to 5 red blood cells [RBCs]/high-power field [HPF]) on a single urinalysis in an asymptomatic person is common and most often a result of menses, allergy, exercise, viral illness, or mild trauma.1

- One study of servicemen, conducted for a period of 10 years, found an incidence of 38%.1

- In one UK population study, first episode of hematuria resulted in a noncancer or cancer diagnosis within 90 days in 17.5% of women (95% confidence interval [CI], 16.4% to 18.6%) and 18.3% of men (95% CI, 17.4% to 19.3%).2

- Persistent (>3 RBCs/HPF over 3 specimens) and significant hematuria (>100 RBCs/HPF or gross hematuria) was associated with significant lesions in 9.1% of more than 1000 patients.1

- In a review of hematuria, approximately 5% of patients with significant microscopic hematuria (>3 RBCs/HPF on 2 of 3 properly collected specimens during a 2- to 3-week period)3 and up to 40% of patients with gross hematuria have a neoplasm.4

- Isolated pyuria (>2 to 10 white blood cells per high-power field [WBCs/HPF]) is uncommon, as inflammatory processes in the urinary tract are usually associated with hematuria.1

- In a laboratory study from 88 institutions, 62.5% of urinalysis tests received a manual microscopic evaluation of the urinary sediment, usually triggered by an abnormal urinalysis. New information was obtained 65% of the time as a result of the manual examination.5

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Hematuria (Figure 67-1) has many causes including:1

- Idiopathic (increasing incidence in the young).

- Stones.

- Neoplasms (increasing incidence with increase in age).

- Trauma.

- Infection/inflammation including acute cystitis, urethritis, pyelonephritis, and prostatitis.

- Benign prostatic hypertrophy.

- Metabolic abnormalities, including hypercalcemia and hyperuricemia.

- Glomerular diseases such as immunoglobulin (Ig) A nephropathy, hereditary nephritis, and thin basement membrane disease.

- Idiopathic (increasing incidence in the young).

- Hematuria with dysmorphic RBCs or RBC casts (Figure 67-2) and excess protein excretion (>500 mg/dL) indicates glomerulonephritis.

- Gross hematuria suggests a postrenal source in the collecting system.

- Pyuria (Figure 67-3) is often the result of urinary tract infection.

- The presence of bacteria (>102 organisms per mL or >105 using a midstream urine specimen) suggests infection. A urinalysis with 10 bacteria per HPF is highly suggestive (specificity 99%) of infection (positive likelihood ratio [LR+] 85).2

- Asymptomatic bacteruria is found in 4% to 15% of pregnant women, usually Escherichia coli.

- The presence of WBC casts (Figure 67-4) with bacteria indicates pyelonephritis.

- The presence of bacteria (>102 organisms per mL or >105 using a midstream urine specimen) suggests infection. A urinalysis with 10 bacteria per HPF is highly suggestive (specificity 99%) of infection (positive likelihood ratio [LR+] 85).2

- WBCs and/or WBC casts can be seen in tubulointerstitial processes like interstitial nephritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or transplant rejection.

- Urinary casts are formed only in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT) or in the collecting duct (distal nephron).

- Hyaline casts are formed from mucoprotein secreted by the tubular epithelial cells within the nephrons. These translucent casts are the most common type of cast and can be seen in normal persons after vigorous exercise or with dehydration. Low urine flow and concentrated urine from dehydration can contribute to the formation of hyaline casts (Figure 67-5).

- Granular casts are the second most common type of cast seen (Figure 67-6). These casts can result from the breakdown of cellular casts or the inclusion of aggregates of albumin or immunoglobulin light chains. They can be classified as fine or coarse based on the size of the inclusions. There is no diagnostic significance to the classification of fine or coarse.