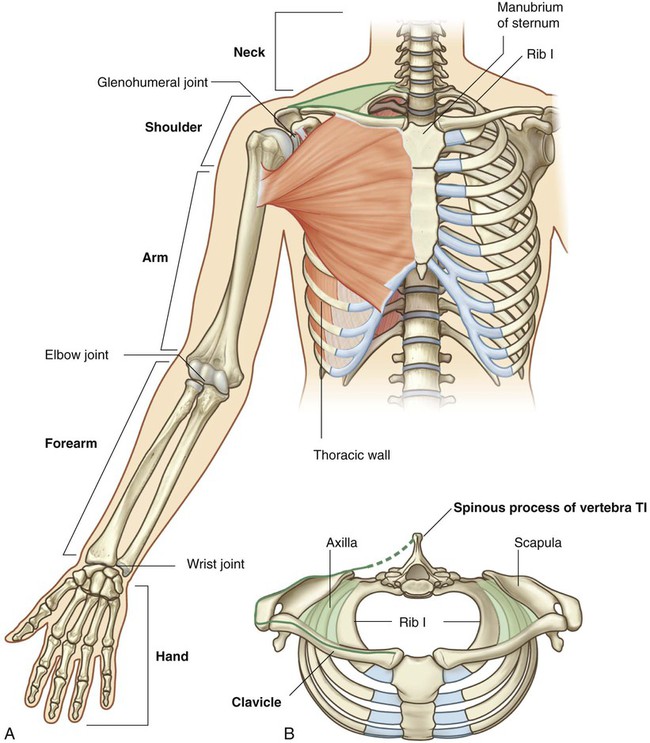

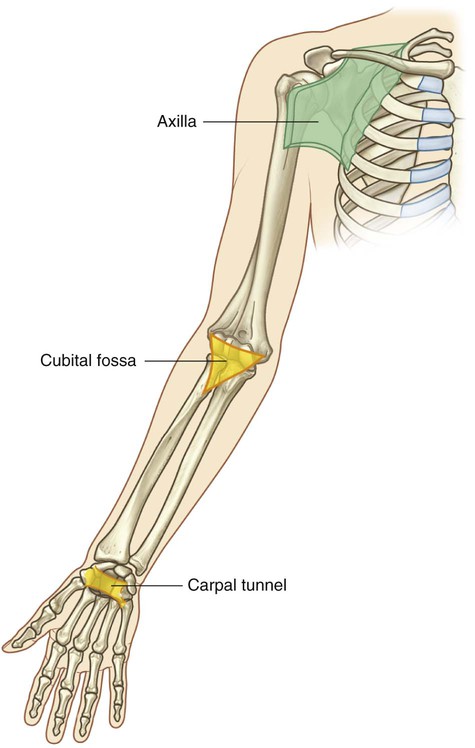

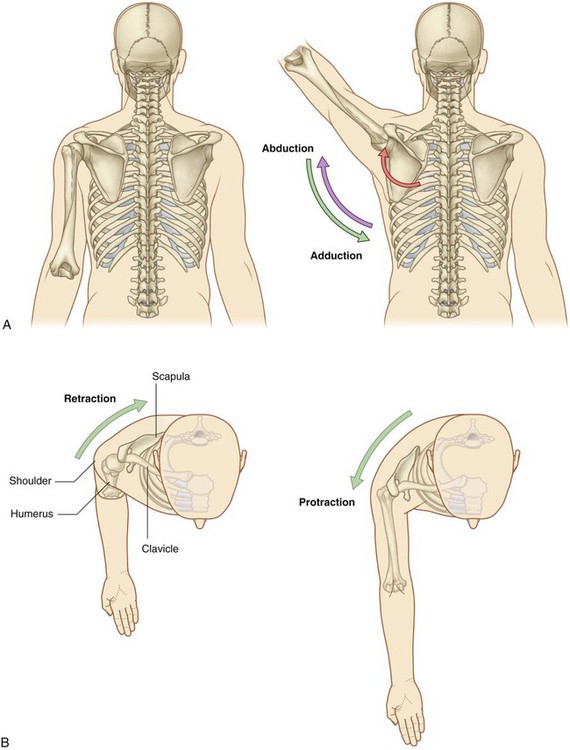

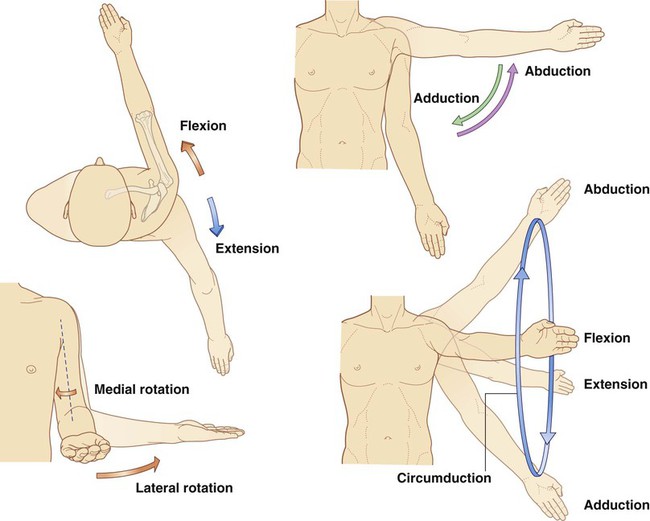

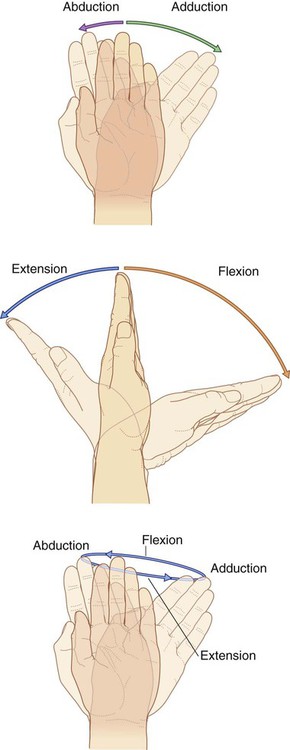

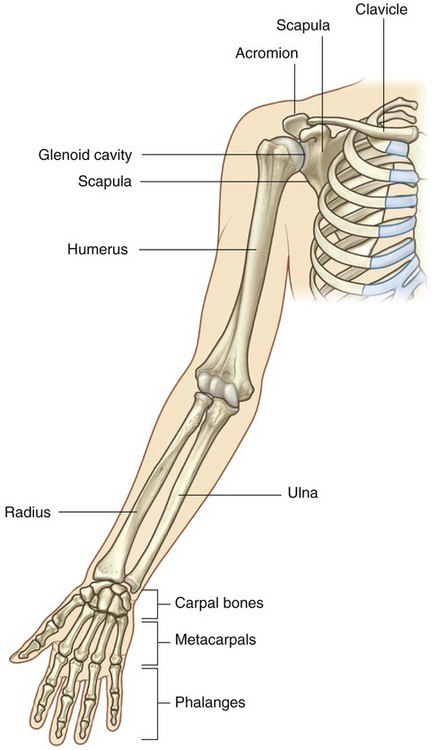

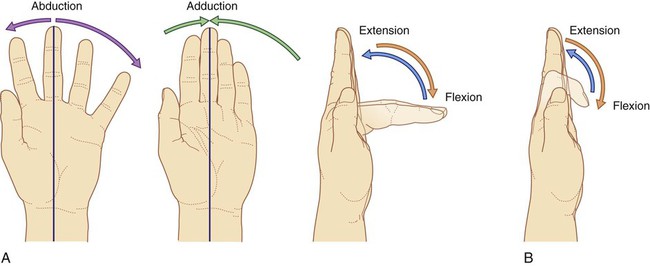

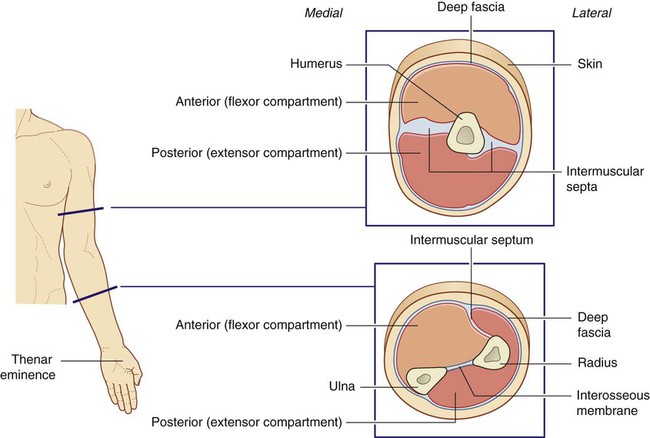

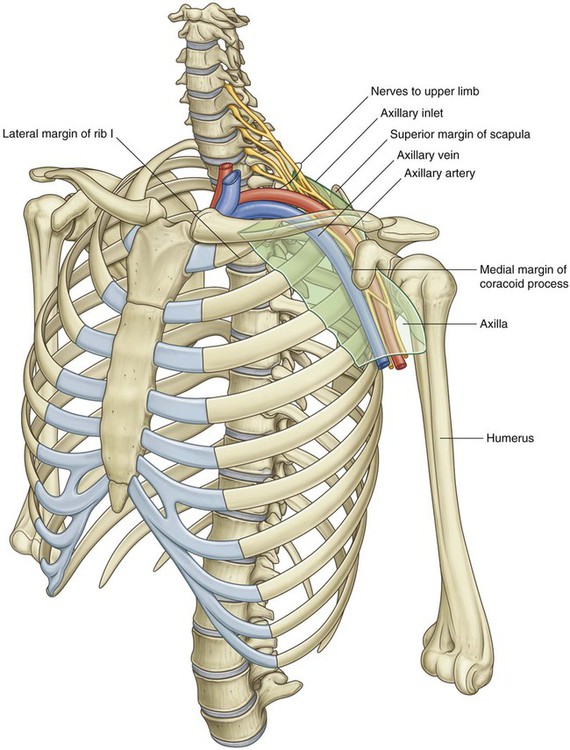

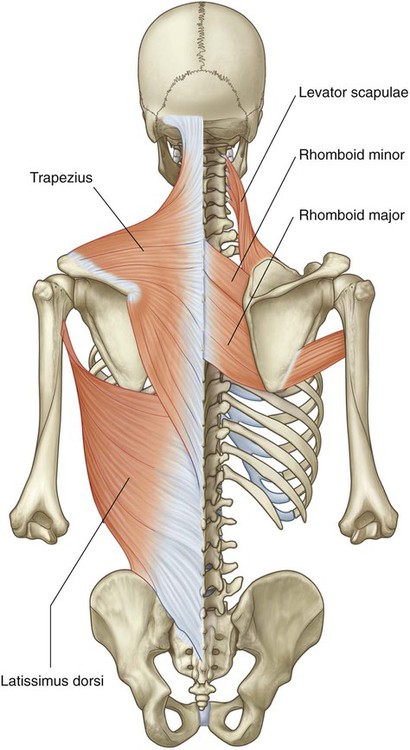

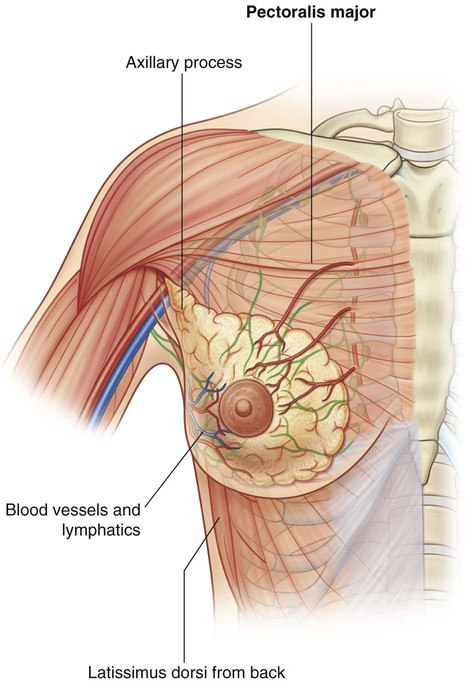

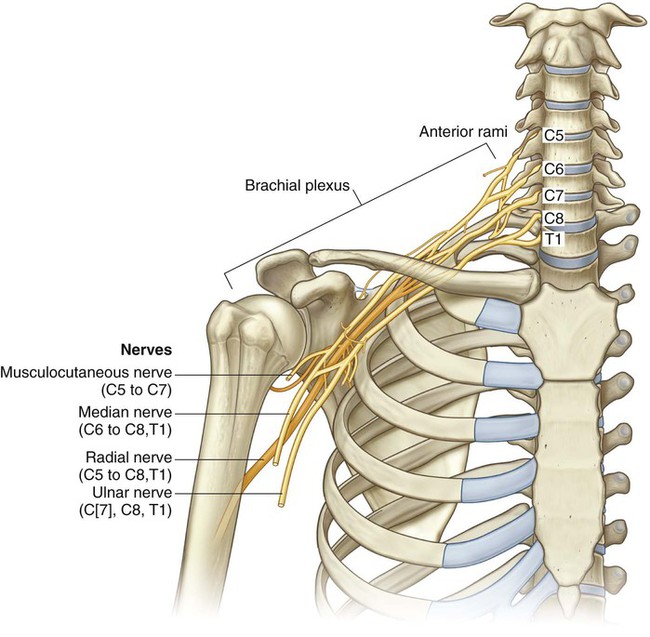

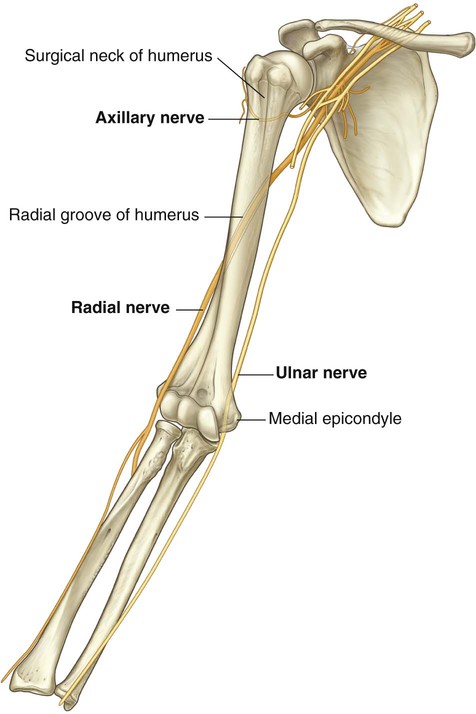

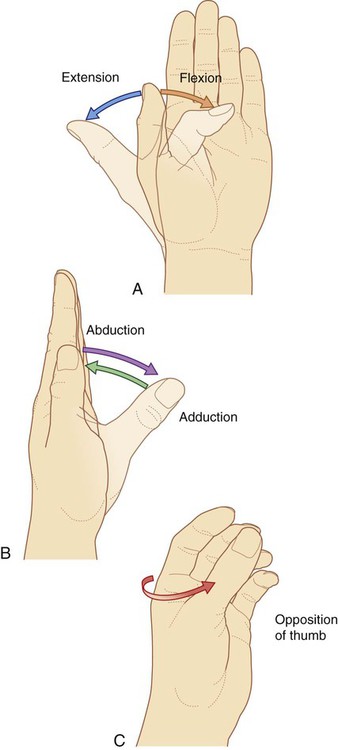

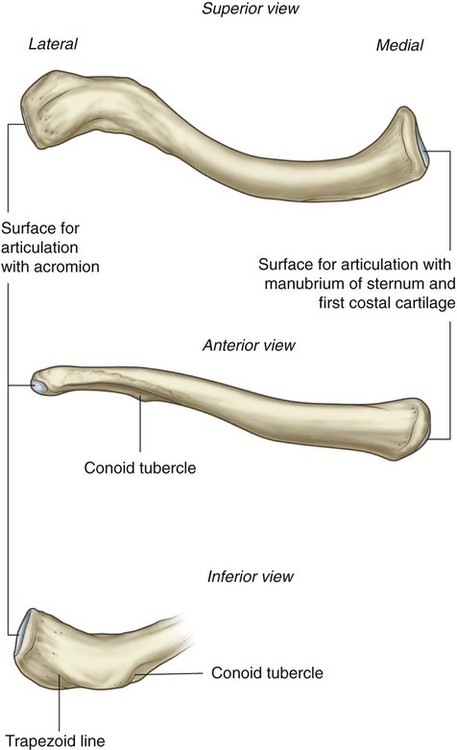

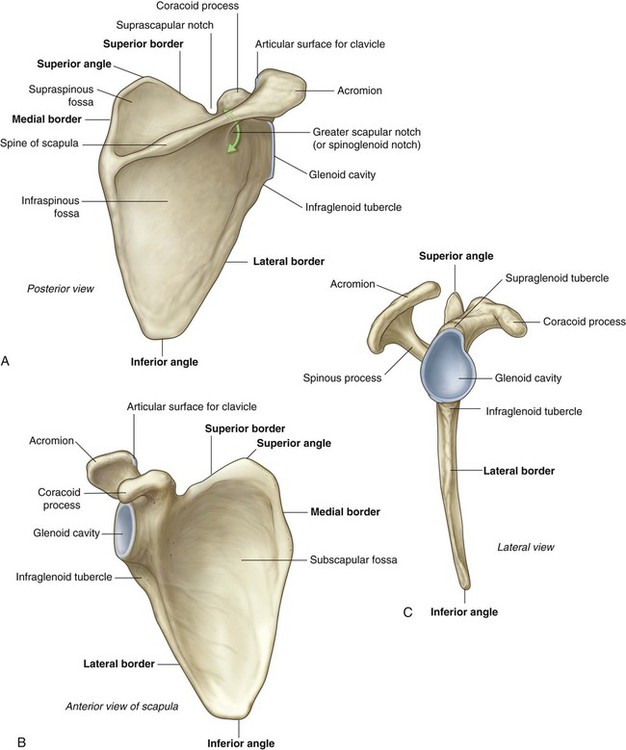

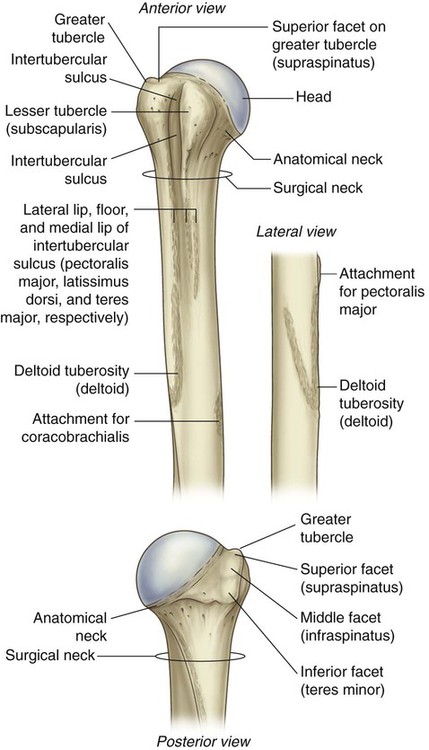

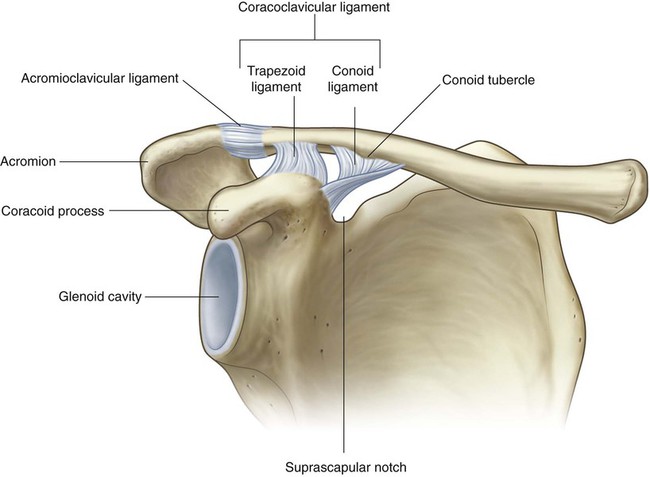

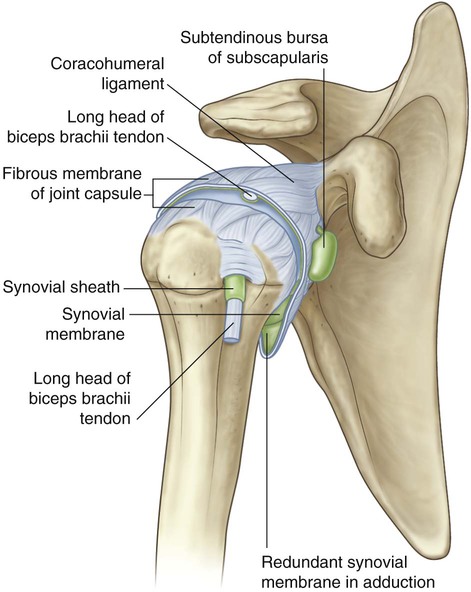

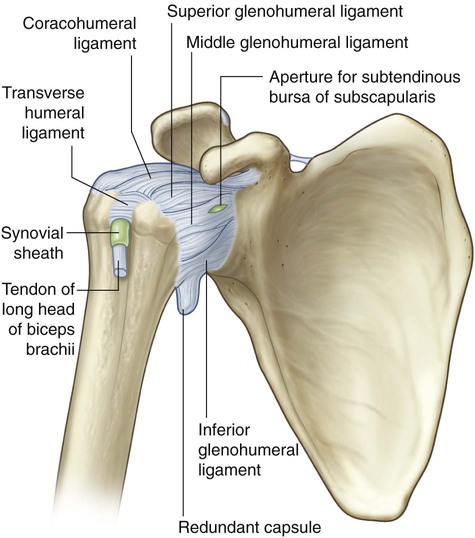

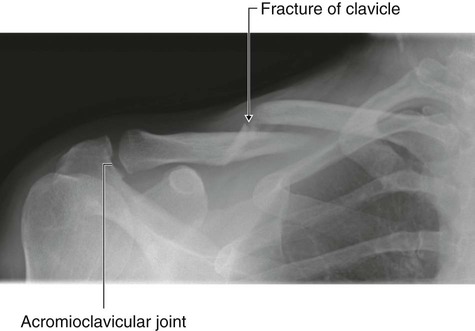

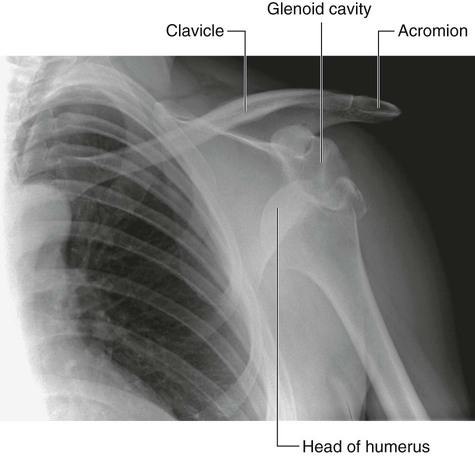

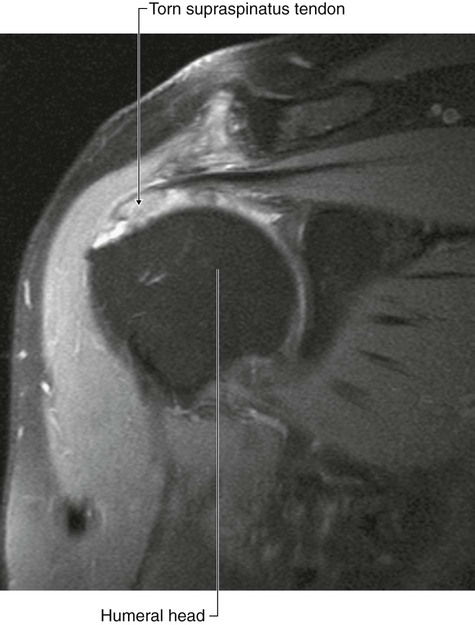

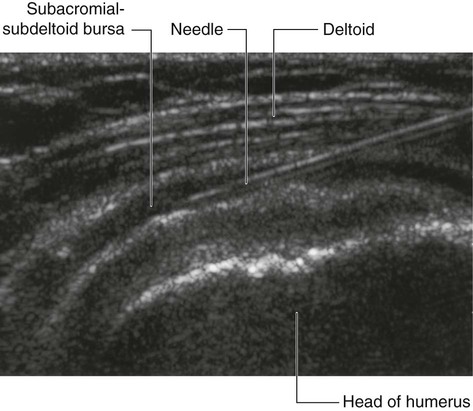

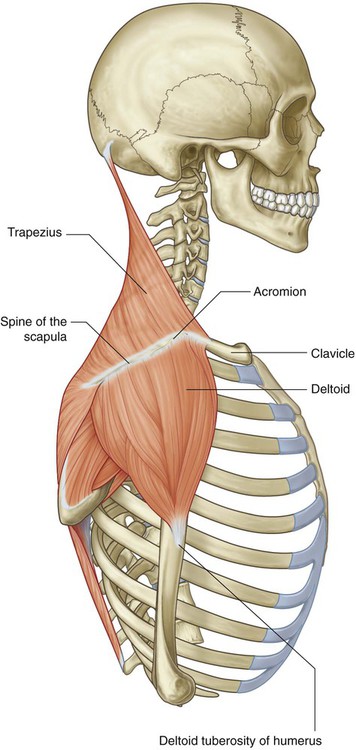

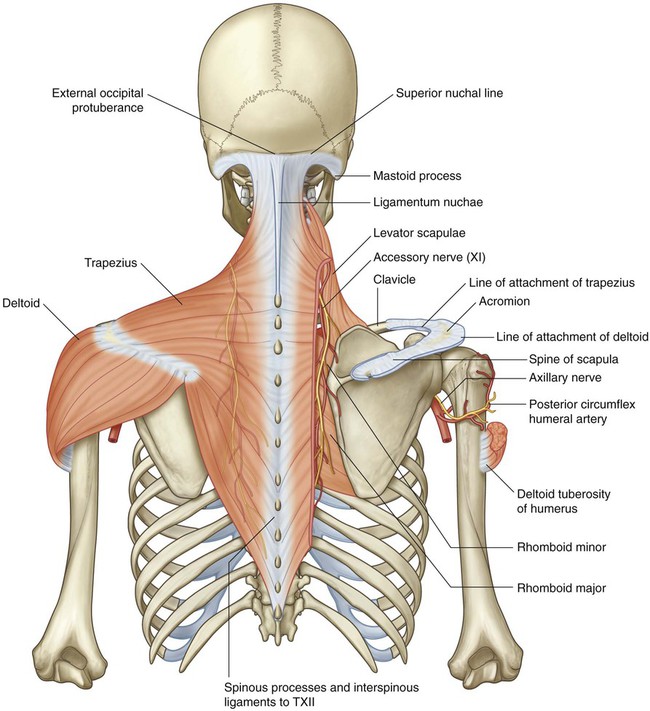

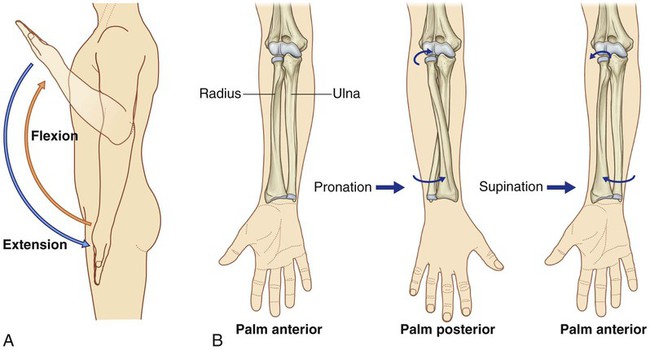

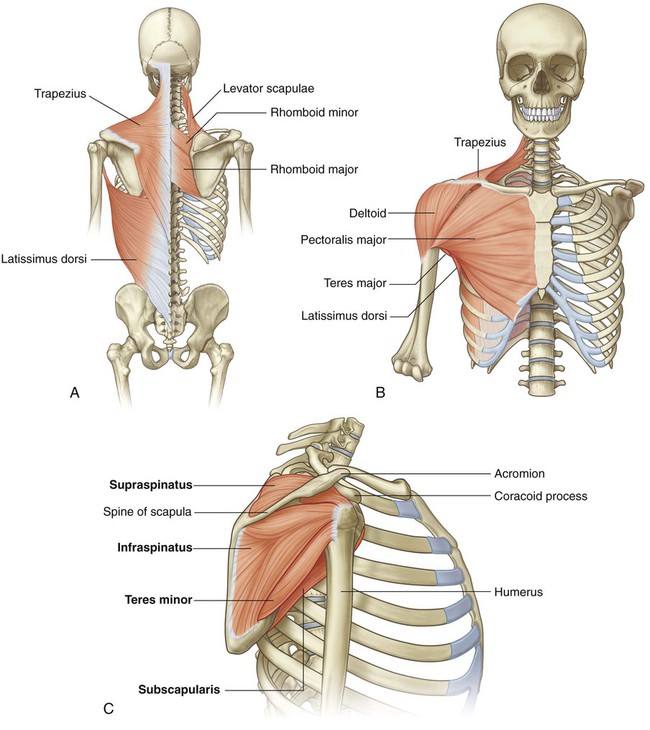

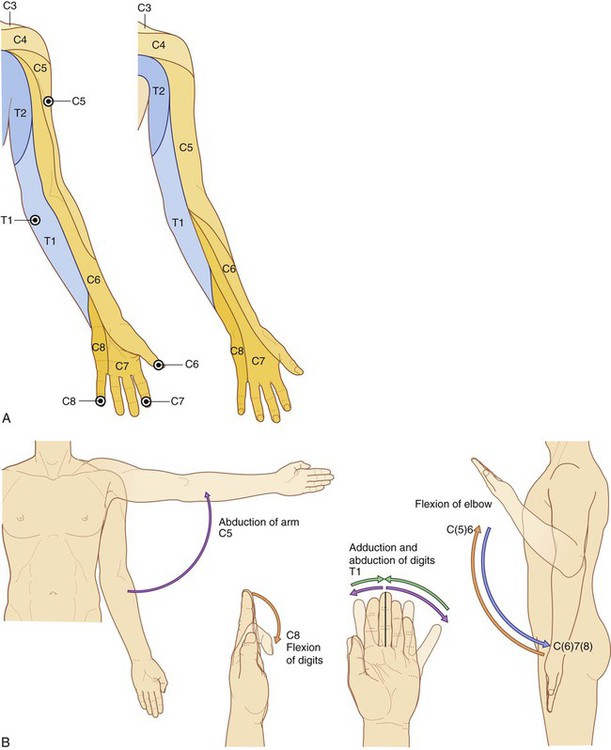

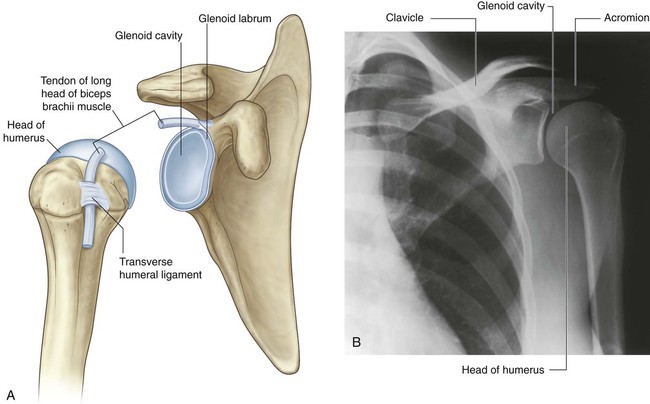

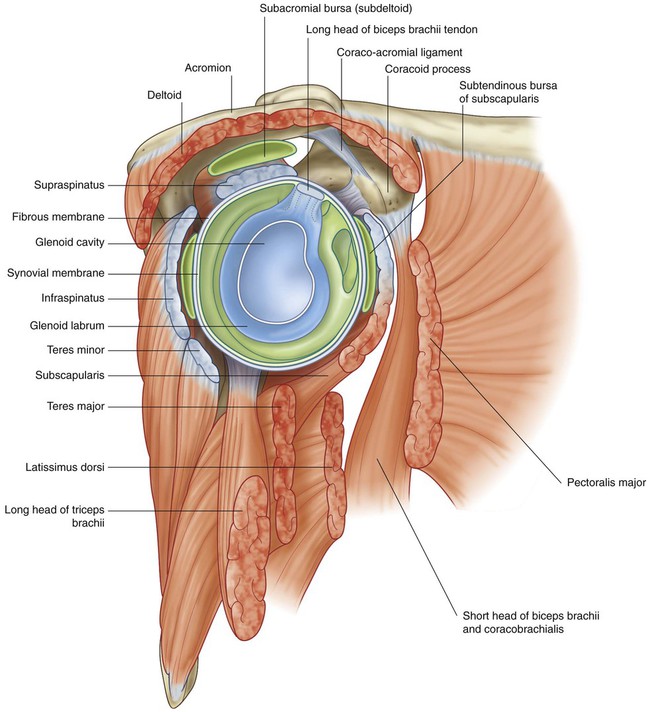

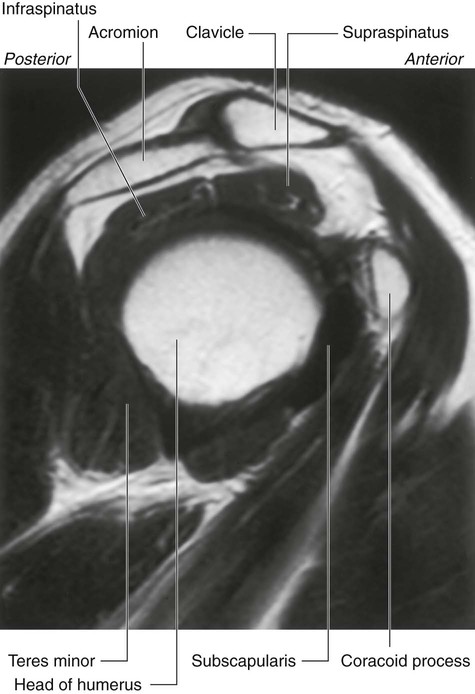

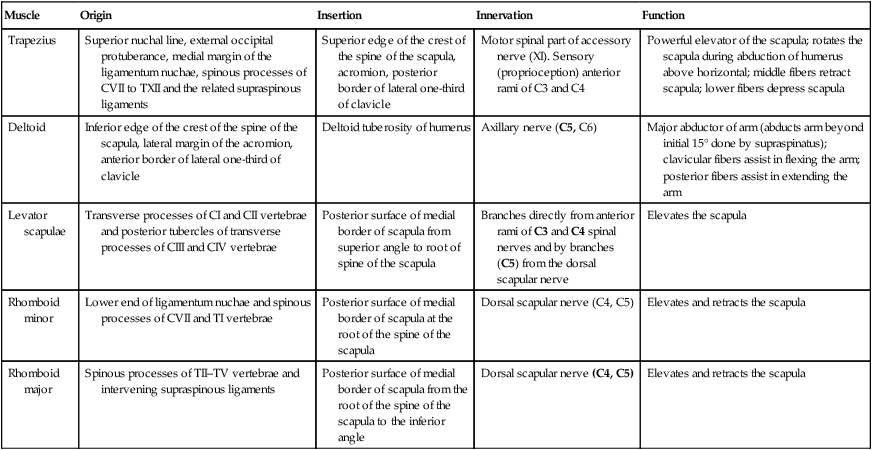

7 ADDITIONAL LEARNING RESOURCES for Chapter 7, Upper Limb, on STUDENT CONSULT (www.studentconsult.com): The upper limb is associated with the lateral aspect of the lower portion of the neck and with the thoracic wall. It is suspended from the trunk by muscles and a small skeletal articulation between the clavicle and the sternum—the sternoclavicular joint. Based on the position of its major joints and component bones, the upper limb is divided into shoulder, arm, forearm, and hand (Fig. 7.1A). The shoulder is the area of upper limb attachment to the trunk (Fig. 7.1B). The axilla, cubital fossa, and carpal tunnel are significant areas of transition between the different parts of the limb (Fig. 7.2). Important structures pass through, or are related to, each of these areas. The shoulder is suspended from the trunk predominantly by muscles and can therefore be moved relative to the body. Sliding (protraction and retraction) and rotating the scapula on the thoracic wall changes the position of the glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint) and extends the reach of the hand (Fig. 7.3). The glenohumeral joint allows the arm to move around three axes with a wide range of motion. Movements of the arm at this joint are flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, medial rotation (internal rotation), lateral rotation (external rotation), and circumduction (Fig. 7.4). The major movements at the elbow joint are flexion and extension of the forearm (Fig. 7.5A). At the other end of the forearm, the distal end of the lateral bone, the radius, can be flipped over the adjacent head of the medial bone, the ulna. Because the hand is articulated with the radius, it can be efficiently moved from a palm-anterior position to a palm-posterior position simply by crossing the distal end of the radius over the ulna (Fig. 7.5B). This movement, termed pronation, occurs solely in the forearm. Supination returns the hand to the anatomical position. At the wrist joint, the hand can be abducted, adducted, flexed, extended, and circumducted (Fig. 7.6). These movements, combined with those of the shoulder, arm, and forearm, enable the hand to be placed in a wide range of positions relative to the body. The bones of the shoulder consist of the scapula, clavicle, and proximal end of the humerus (Fig. 7.7). The humerus is the bone of the arm (Fig. 7.7). The distal end of the humerus articulates with the bones of the forearm at the elbow joint, which is a hinge joint that allows flexion and extension of the forearm. The forearm contains two bones: The bones of the hand consist of the carpal bones, the metacarpals, and the phalanges (Fig. 7.7). The five digits in the hand are the thumb and the index, middle, ring, and little fingers. The five metacarpals, one for each digit, are the primary skeletal foundation of the palm (Fig. 7.7). The bones of the digits are the phalanges (Fig. 7.7). The thumb has two phalanges, while each of the other digits has three. The metacarpophalangeal joints are biaxial condylar joints (ellipsoid joints) that allow abduction, adduction, flexion, extension, and circumduction (Fig. 7.8). Abduction and adduction of the fingers is defined in reference to an axis passing through the center of the middle finger in the anatomical position. The middle finger can therefore abduct both medially and laterally and adduct back to the central axis from either side. The interphalangeal joints are primarily hinge joints that allow only flexion and extension. Some muscles of the shoulder, such as the trapezius, levator scapulae, and rhomboids, connect the scapula and clavicle to the trunk. Other muscles connect the clavicle, scapula, and body wall to the proximal end of the humerus. These include the pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, latissimus dorsi, teres major, and deltoid (Fig. 7.9A,B). The most important of these muscles are the four rotator cuff muscles—the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor muscles—which connect the scapula to the humerus and provide support for the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 7.9C). Muscles in the arm and forearm are separated into anterior (flexor) and posterior (extensor) compartments by layers of fascia, bones, and ligaments (Fig. 7.10). In the forearm, the anterior and posterior compartments are separated by a lateral intermuscular septum, the radius, the ulna, and an interosseous membrane, which joins adjacent sides of the radius and ulna (Fig. 7.10). Muscles that attach the bones of the shoulder to the trunk are associated with the back and the thoracic wall and include the trapezius, levator scapulae, rhomboid major, rhomboid minor, and latissimus dorsi (Fig. 7.12). The breast on the anterior thoracic wall has a number of significant relationships with the axilla and upper limb. It overlies the pectoralis major muscle, which forms most of the anterior wall of the axilla and attaches the humerus to the chest wall (Fig. 7.13). Often, part of the breast known as the axillary process extends around the lateral margin of the pectoralis major into the axilla. Innervation of the upper limb is by the brachial plexus, which is formed by the anterior rami of cervical spinal nerves C5 to C8, and T1 (Fig. 7.14). This plexus is initially formed in the neck and then continues through the axillary inlet into the axilla. Major nerves that ultimately innervate the arm, forearm, and hand originate from the brachial plexus in the axilla. Dermatomes of the upper limb (Fig. 7.15A) are often tested for sensation. Areas where overlap of dermatomes is minimal include the: Selected joint movements are used to test myotomes (Fig. 7.15B): Each of the major muscle compartments in the arm and forearm and each of the intrinsic muscles of the hand is innervated predominantly by one of the major nerves that originate from the brachial plexus in the axilla (Fig. 7.16A): In addition to innervating major muscle groups, each of the major peripheral nerves originating from the brachial plexus carries somatic sensory information from patches of skin quite different from dermatomes (Fig. 7.16B). Sensation in these areas can be used to test for peripheral nerve lesions: Three important nerves are directly related to parts of the humerus (Fig. 7.17): Fractures of the humerus in any one of these three regions can endanger the related nerve. Large veins embedded in the superficial fascia of the upper limb are often used to access a patient’s vascular system and to withdraw blood. The most significant of these veins are the cephalic, basilic, and median cubital veins (Fig. 7.18). The cephalic and basilic veins originate from the dorsal venous network on the back of the hand. The thumb is positioned at right angles to the orientation of the index, middle, ring, and little fingers (Fig. 7.19). As a result, movements of the thumb occur at right angles to those of the other digits. For example, flexion brings the thumb across the palm, whereas abduction moves it away from the fingers at right angles to the palm. The shoulder is the region of upper limb attachment to the trunk. The bone framework of the shoulder consists of: The clavicle is the only bony attachment between the trunk and the upper limb. It is palpable along its entire length and has a gentle S-shaped contour, with the forward-facing convex part medial and the forward-facing concave part lateral. The acromial (lateral) end of the clavicle is flat, whereas the sternal (medial) end is more robust and somewhat quadrangular in shape (Fig. 7.20). The scapula is a large, flat triangular bone with: The lateral angle of the scapula is marked by a shallow, somewhat comma-shaped glenoid cavity, which articulates with the head of the humerus to form the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 7.21B,C). A prominent spine subdivides the posterior surface of the scapula into a small, superior supraspinous fossa and a much larger, inferior infraspinous fossa (Fig. 7.21A). Unlike the posterior surface, the costal surface of the scapula is unremarkable, being characterized by a shallow concave subscapular fossa over much of its extent (Fig. 7.21B). The costal surface and margins provide for muscle attachment, and the costal surface, together with its related muscle (subscapularis), moves freely over the underlying thoracic wall. The superior border is marked on its lateral end by: The proximal end of the humerus consists of the head, the anatomical neck, the greater and lesser tubercles, the surgical neck, and the superior half of the shaft of the humerus (Fig. 7.22). A deep intertubercular sulcus (bicipital groove) separates the lesser and greater tubercles and continues inferiorly onto the proximal shaft of the humerus (Fig. 7.22). The tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii passes through this sulcus. The lateral lip of the intertubercular sulcus is continuous inferiorly with a large V-shaped deltoid tuberosity on the lateral surface of the humerus midway along its length (Fig. 7.22), which is where the deltoid muscle inserts onto the humerus. One of the most important features of the proximal end of the humerus is the surgical neck (Fig. 7.22). This region is oriented in the horizontal plane between the expanded proximal part of the humerus (head, anatomical neck, and tubercles) and the narrower shaft. The axillary nerve and the posterior circumflex humeral artery, which pass into the deltoid region from the axilla, do so immediately posterior to the surgical neck. Because the surgical neck is weaker than more proximal regions of the bone, it is one of the sites where the humerus commonly fractures. The associated nerve (axillary) and artery (posterior circumflex humeral) can be damaged by fractures in this region. The sternoclavicular joint occurs between the proximal end of the clavicle and the clavicular notch of the manubrium of the sternum together with a small part of the first costal cartilage (Fig. 7.23). It is synovial and saddle shaped. The articular cavity is completely separated into two compartments by an articular disc. The sternoclavicular joint allows movement of the clavicle, predominantly in the anteroposterior and vertical planes, although some rotation also occurs. The sternoclavicular joint is surrounded by a joint capsule and is reinforced by four ligaments: The acromioclavicular joint is a small synovial joint between an oval facet on the medial surface of the acromion and a similar facet on the acromial end of the clavicle (Fig. 7.24, also see Fig. 7.31). It allows movement in the anteroposterior and vertical planes together with some axial rotation. The acromioclavicular joint is surrounded by a joint capsule and is reinforced by: The glenohumeral joint is a synovial ball and socket articulation between the head of the humerus and the glenoid cavity of the scapula (Fig. 7.25). It is multiaxial with a wide range of movements provided at the cost of skeletal stability. Joint stability is provided, instead, by the rotator cuff muscles, the long head of the biceps brachii muscle, related bony processes, and extracapsular ligaments. Movements at the joint include flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, medial rotation, lateral rotation, and circumduction. The articular surfaces of the glenohumeral joint are the large spherical head of the humerus and the small glenoid cavity of the scapula (Fig. 7.25). Each of the surfaces is covered by hyaline cartilage. The synovial membrane attaches to the margins of the articular surfaces and lines the fibrous membrane of the joint capsule (Fig. 7.26). The synovial membrane is loose inferiorly. This redundant region of synovial membrane and related fibrous membrane accommodates abduction of the arm. The fibrous membrane of the joint capsule attaches to the margin of the glenoid cavity, outside the attachment of the glenoid labrum and the long head of the biceps brachii muscle, and to the anatomical neck of the humerus (Fig. 7.27). The fibrous membrane of the joint capsule is thickened: Joint stability is provided by surrounding muscle tendons and a skeletal arch formed superiorly by the coracoid process and acromion and the coraco-acromial ligament (Fig. 7.28). Tendons of the rotator cuff muscles (the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis muscles) blend with the joint capsule and form a musculotendinous collar that surrounds the posterior, superior, and anterior aspects of the glenohumeral joint (Figs. 7.28 and 7.29). This cuff of muscles stabilizes and holds the head of the humerus in the glenoid cavity of the scapula without compromising the arm’s flexibility and range of motion. The tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii muscle passes superiorly through the joint and restricts upward movement of the humeral head on the glenoid cavity. The two most superficial muscles of the shoulder are the trapezius and deltoid muscles (Fig. 7.35 and Table 7.1). Together, they provide the characteristic contour of the shoulder: Table 7.1 Muscles of the shoulder (spinal segments in bold are the major segments innervating the muscle) The trapezius muscle has an extensive origin from the axial skeleton, which includes sites on the skull and the vertebrae, from CI to TXII (Fig. 7.36). From CI to CVII, the muscle attaches to the vertebrae through the ligamentum nuchae. The muscle inserts onto the skeletal framework of the shoulder along the inner margins of a continuous U-shaped line of attachment oriented in the horizontal plane, with the bottom of the U directed laterally. Together, the left and right trapezius muscles form a diamond or trapezoid shape, from which the name is derived.

Upper Limb

Conceptual overview

General description

Functions

Positioning the hand

Component parts

Bones and joints

Muscles

Relationship to other regions

Neck

the posterior surface of the clavicle,

the posterior surface of the clavicle,

the superior margin of the scapula, and

the superior margin of the scapula, and

the medial surface of the coracoid process of the scapula (Fig. 7.11).

the medial surface of the coracoid process of the scapula (Fig. 7.11).

Back and thoracic wall

Key points

Innervation by cervical and upper thoracic nerves

upper lateral region of the arm for spinal cord level C5,

upper lateral region of the arm for spinal cord level C5,

palmar pad of the thumb for spinal cord level C6,

palmar pad of the thumb for spinal cord level C6,

pad of the index finger for spinal cord level C7,

pad of the index finger for spinal cord level C7,

pad of the little finger for spinal cord level C8, and

pad of the little finger for spinal cord level C8, and

skin on the medial aspect of the elbow for spinal cord level T1.

skin on the medial aspect of the elbow for spinal cord level T1.

Abduction of the arm at the glenohumeral joint is controlled predominantly by C5.

Abduction of the arm at the glenohumeral joint is controlled predominantly by C5.

Flexion of the forearm at the elbow joint is controlled primarily by C6.

Flexion of the forearm at the elbow joint is controlled primarily by C6.

Extension of the forearm at the elbow joint is controlled mainly by C7.

Extension of the forearm at the elbow joint is controlled mainly by C7.

Flexion of the fingers is controlled mainly by C8.

Flexion of the fingers is controlled mainly by C8.

Abduction and adduction of the index, middle, and ring fingers is controlled predominantly by T1.

Abduction and adduction of the index, middle, and ring fingers is controlled predominantly by T1.

A tap on the tendon of the biceps in the cubital fossa tests mainly for spinal cord level C6.

A tap on the tendon of the biceps in the cubital fossa tests mainly for spinal cord level C6.

A tap on the tendon of the triceps posterior to the elbow tests mainly for C7.

A tap on the tendon of the triceps posterior to the elbow tests mainly for C7.

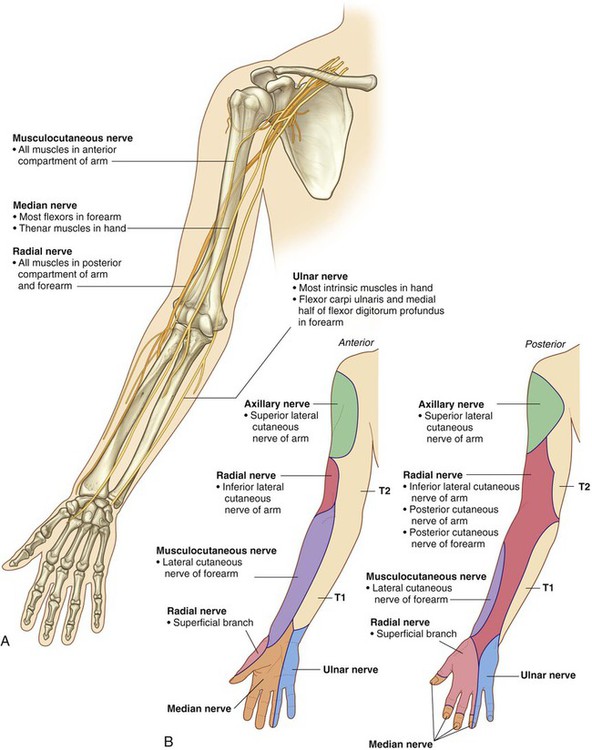

All muscles in the anterior compartment of the arm are innervated by the musculocutaneous nerve.

All muscles in the anterior compartment of the arm are innervated by the musculocutaneous nerve.

The median nerve innervates the muscles in the anterior compartment of the forearm, with two exceptions—one flexor of the wrist (the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle) and part of one flexor of the fingers (the medial half of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle) are innervated by the ulnar nerve.

The median nerve innervates the muscles in the anterior compartment of the forearm, with two exceptions—one flexor of the wrist (the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle) and part of one flexor of the fingers (the medial half of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle) are innervated by the ulnar nerve.

Most intrinsic muscles of the hand are innervated by the ulnar nerve, except for the thenar muscles and two lateral lumbrical muscles, which are innervated by the median nerve.

Most intrinsic muscles of the hand are innervated by the ulnar nerve, except for the thenar muscles and two lateral lumbrical muscles, which are innervated by the median nerve.

All muscles in the posterior compartments of the arm and forearm are innervated by the radial nerve.

All muscles in the posterior compartments of the arm and forearm are innervated by the radial nerve.

The musculocutaneous nerve innervates skin on the anterolateral side of the forearm.

The musculocutaneous nerve innervates skin on the anterolateral side of the forearm.

The median nerve innervates the palmar surface of the lateral three and one-half digits, and the ulnar nerve innervates the medial one and one-half digits.

The median nerve innervates the palmar surface of the lateral three and one-half digits, and the ulnar nerve innervates the medial one and one-half digits.

The radial nerve supplies skin on the posterior surface of the forearm and the dorsolateral surface of the hand.

The radial nerve supplies skin on the posterior surface of the forearm and the dorsolateral surface of the hand.

Nerves related to bone

The axillary nerve, which supplies the deltoid muscle, a major abductor of the humerus at the glenohumeral joint, passes around the posterior aspect of the upper part of the humerus (the surgical neck).

The axillary nerve, which supplies the deltoid muscle, a major abductor of the humerus at the glenohumeral joint, passes around the posterior aspect of the upper part of the humerus (the surgical neck).

The radial nerve, which supplies all of the extensor muscles of the upper limb, passes diagonally around the posterior surface of the middle of the humerus in the radial groove.

The radial nerve, which supplies all of the extensor muscles of the upper limb, passes diagonally around the posterior surface of the middle of the humerus in the radial groove.

The ulnar nerve, which is ultimately destined for the hand, passes posteriorly to a bony protrusion, the medial epicondyle, on the medial side of the distal end of the humerus.

The ulnar nerve, which is ultimately destined for the hand, passes posteriorly to a bony protrusion, the medial epicondyle, on the medial side of the distal end of the humerus.

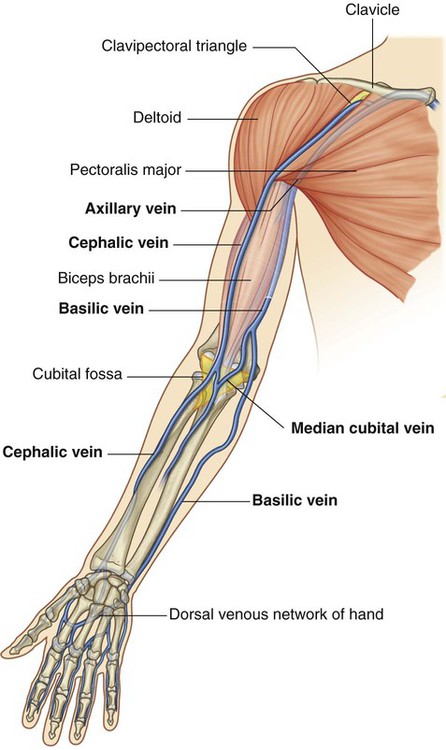

Superficial veins

Orientation of the thumb

Regional anatomy

Shoulder

Bones

Clavicle

Scapula

three angles (lateral, superior, and inferior),

three angles (lateral, superior, and inferior),

three borders (superior, lateral, and medial),

three borders (superior, lateral, and medial),

two surfaces (costal and posterior), and

two surfaces (costal and posterior), and

three processes (acromion, spine, and coracoid process) (Fig. 7.21).

three processes (acromion, spine, and coracoid process) (Fig. 7.21).

the coracoid process, a hook-like structure that projects anterolaterally and is positioned directly inferior to the lateral part of the clavicle; and

the coracoid process, a hook-like structure that projects anterolaterally and is positioned directly inferior to the lateral part of the clavicle; and

the small but distinct suprascapular notch, which lies immediately medial to the root of the coracoid process.

the small but distinct suprascapular notch, which lies immediately medial to the root of the coracoid process.

Proximal humerus

Greater and lesser tubercles

The superior facet is for attachment of the supraspinatus muscle.

The superior facet is for attachment of the supraspinatus muscle.

The middle facet is for attachment of the infraspinatus.

The middle facet is for attachment of the infraspinatus.

Surgical neck

Joints

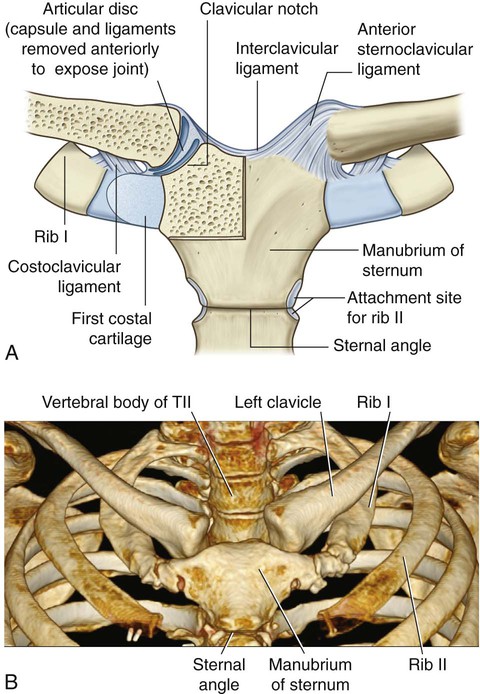

Sternoclavicular joint

The anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments are anterior and posterior, respectively, to the joint.

The anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments are anterior and posterior, respectively, to the joint.

An interclavicular ligament links the ends of the two clavicles to each other and to the superior surface of the manubrium of the sternum.

An interclavicular ligament links the ends of the two clavicles to each other and to the superior surface of the manubrium of the sternum.

The costoclavicular ligament is positioned laterally to the joint and links the proximal end of the clavicle to the first rib and related costal cartilage.

The costoclavicular ligament is positioned laterally to the joint and links the proximal end of the clavicle to the first rib and related costal cartilage.

Acromioclavicular joint

a small acromioclavicular ligament superior to the joint and passing between adjacent regions of the clavicle and acromion, and

a small acromioclavicular ligament superior to the joint and passing between adjacent regions of the clavicle and acromion, and

a much larger coracoclavicular ligament, which is not directly related to the joint, but is an important strong accessory ligament, providing much of the weight-bearing support for the upper limb on the clavicle and maintaining the position of the clavicle on the acromion—it spans the distance between the coracoid process of the scapula and the inferior surface of the acromial end of the clavicle and comprises an anterior trapezoid ligament (which attaches to the trapezoid line on the clavicle) and a posterior conoid ligament (which attaches to the related conoid tubercle).

a much larger coracoclavicular ligament, which is not directly related to the joint, but is an important strong accessory ligament, providing much of the weight-bearing support for the upper limb on the clavicle and maintaining the position of the clavicle on the acromion—it spans the distance between the coracoid process of the scapula and the inferior surface of the acromial end of the clavicle and comprises an anterior trapezoid ligament (which attaches to the trapezoid line on the clavicle) and a posterior conoid ligament (which attaches to the related conoid tubercle).

Glenohumeral joint

between the acromion (or deltoid muscle) and supraspinatus muscle (or joint capsule) (the subacromial or subdeltoid bursa),

between the acromion (or deltoid muscle) and supraspinatus muscle (or joint capsule) (the subacromial or subdeltoid bursa),

between the acromion and skin,

between the acromion and skin,

between the coracoid process and the joint capsule, and

between the coracoid process and the joint capsule, and

in relationship to tendons of muscles around the joint (coracobrachialis, teres major, long head of triceps brachii, and latissimus dorsi muscles).

in relationship to tendons of muscles around the joint (coracobrachialis, teres major, long head of triceps brachii, and latissimus dorsi muscles).

anterosuperiorly in three locations to form superior, middle, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments, which pass from the superomedial margin of the glenoid cavity to the lesser tubercle and inferiorly related anatomical neck of the humerus (Fig. 7.27);

anterosuperiorly in three locations to form superior, middle, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments, which pass from the superomedial margin of the glenoid cavity to the lesser tubercle and inferiorly related anatomical neck of the humerus (Fig. 7.27);

superiorly between the base of the coracoid process and the greater tubercle of the humerus (the coracohumeral ligament); and

superiorly between the base of the coracoid process and the greater tubercle of the humerus (the coracohumeral ligament); and

between the greater and lesser tubercles of the humerus (transverse humeral ligament)—this holds the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii muscle in the intertubercular sulcus (Fig. 7.27).

between the greater and lesser tubercles of the humerus (transverse humeral ligament)—this holds the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii muscle in the intertubercular sulcus (Fig. 7.27).

Muscles

Muscle

Origin

Insertion

Innervation

Function

Trapezius

Superior nuchal line, external occipital protuberance, medial margin of the ligamentum nuchae, spinous processes of CVII to TXII and the related supraspinous ligaments

Superior edge of the crest of the spine of the scapula, acromion, posterior border of lateral one-third of clavicle

Motor spinal part of accessory nerve (XI). Sensory (proprioception) anterior rami of C3 and C4

Powerful elevator of the scapula; rotates the scapula during abduction of humerus above horizontal; middle fibers retract scapula; lower fibers depress scapula

Deltoid

Inferior edge of the crest of the spine of the scapula, lateral margin of the acromion, anterior border of lateral one-third of clavicle

Deltoid tuberosity of humerus

Axillary nerve (C5, C6)

Major abductor of arm (abducts arm beyond initial 15° done by supraspinatus); clavicular fibers assist in flexing the arm; posterior fibers assist in extending the arm

Levator scapulae

Transverse processes of CI and CII vertebrae and posterior tubercles of transverse processes of CIII and CIV vertebrae

Posterior surface of medial border of scapula from superior angle to root of spine of the scapula

Branches directly from anterior rami of C3 and C4 spinal nerves and by branches (C5) from the dorsal scapular nerve

Elevates the scapula

Rhomboid minor

Lower end of ligamentum nuchae and spinous processes of CVII and TI vertebrae

Posterior surface of medial border of scapula at the root of the spine of the scapula

Dorsal scapular nerve (C4, C5)

Elevates and retracts the scapula

Rhomboid major

Spinous processes of TII–TV vertebrae and intervening supraspinous ligaments

Posterior surface of medial border of scapula from the root of the spine of the scapula to the inferior angle

Dorsal scapular nerve (C4, C5)

Elevates and retracts the scapula

The trapezius attaches the scapula and clavicle to the trunk.

The trapezius attaches the scapula and clavicle to the trunk.

The deltoid attaches the scapula and clavicle to the humerus.

The deltoid attaches the scapula and clavicle to the humerus.

Trapezius

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Upper Limb