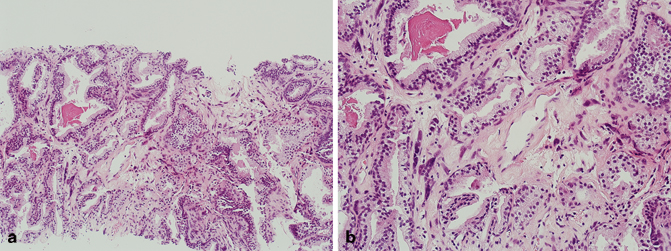

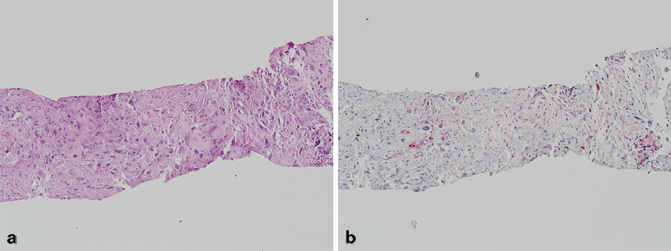

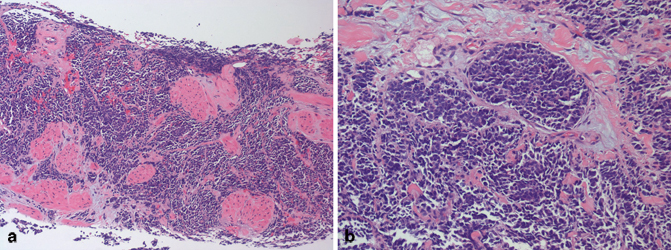

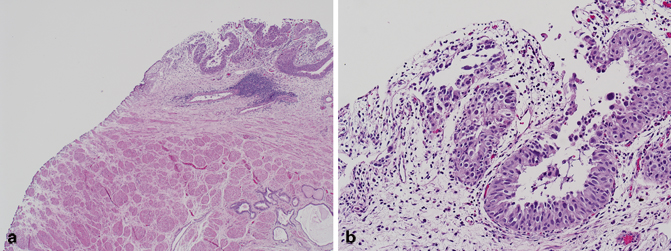

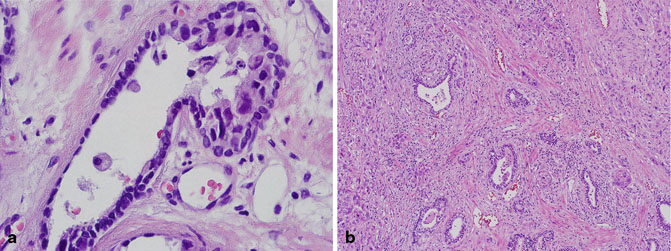

Fig. 5.1

a Radical prostatectomy, mucinous adenocarcinoma (low magnification). b Radical prostatectomy, mucinous adenocarcinoma (high magnification)

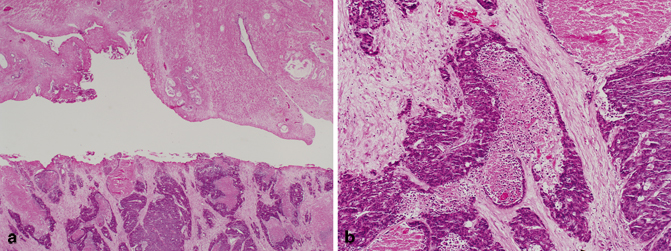

Prostatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

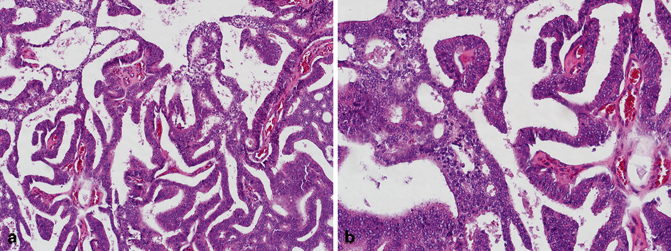

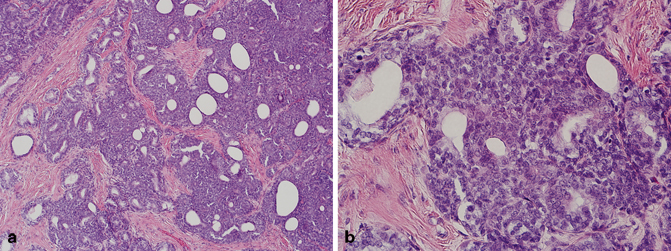

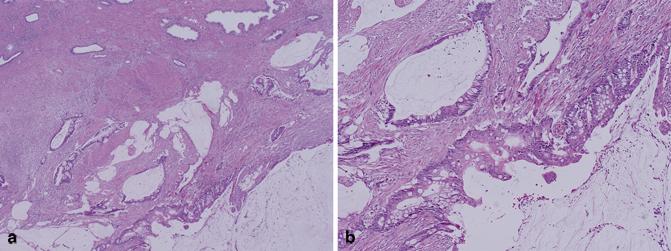

Prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma is a rare variant of prostate cancer that was previously referred to as endometrioid carcinoma, endometrial carcinoma, or papillary ductal carcinoma [8−11]. The incidence of the pure form of this variant is approximately 0.5–1.0 %; however, the incidence of the more common mixed prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma and conventional acinar adenocarcinoma is approximately 5 % [1, 2, 12]. These tumors are composed of papillary fronds lined by pseudostratified columnar epithelial cells with amphophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 5.2). Basal cells are typically absent, but may be present focally as demonstrated by basal cell markers in a patchy distribution. Prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma typically arises from the periurethral region but can extend to the peripheral zone and extraprostatic tissue including the bladder, confirming the aggressive nature of the majority of these tumors. A Gleason score of 4 + 4 = 8 is assigned to tumors composed entirely of classic prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma. If comedonecrosis is present, then the Gleason score has to be increased accordingly. It should also be noted that a Gleason score of 3 + 3 = 6 should be assigned to tumors composed entirely of the recently described “High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia-like ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate” [13, 14]. Although immunohistochemical stains are typically positive for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and prostatic acid phosphatase (PSAP), serum PSA level may occasionally be normal.

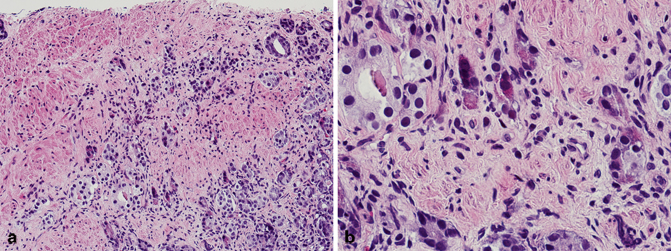

Fig. 5.2

a Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma (low magnification). b TURP, prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma (high magnification)

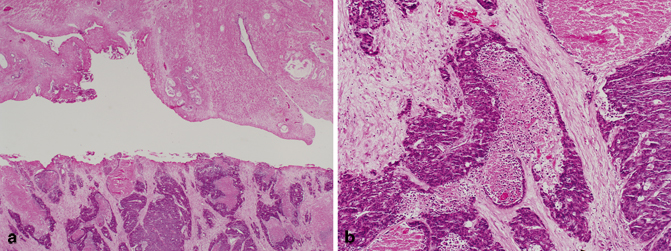

Intraductal Carcinoma of the Prostate

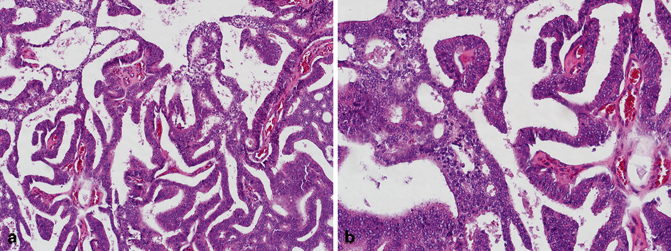

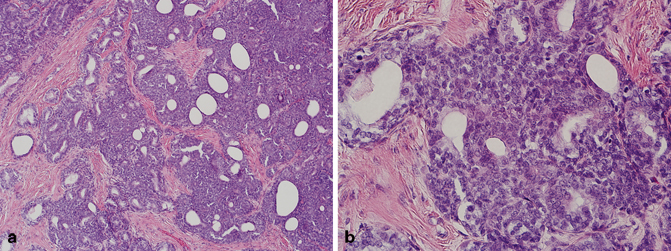

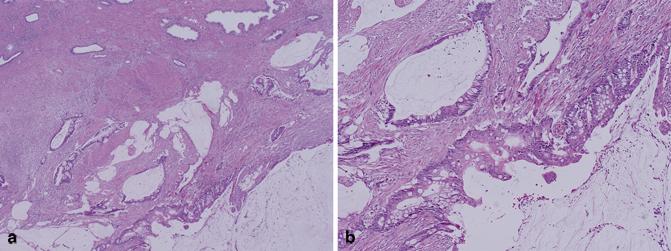

Although there are some similarities between prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma and intraductal carcinoma of the prostate (including bad prognosis) , they are somewhat distinct entities. Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate is composed of an expansile proliferation of malignant prostatic epithelial cells that spans the entire lumen of prostatic ducts or acini, while the normal architecture of ducts or acini are still maintained [15−19]. In contrast to prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma, in intraductal carcinoma of the prostate, basal cells are always present (Fig. 5.3) and distinguish this entity from conventional cribriform Gleason pattern/grade 4 cancer. Tumor cells are typically cuboidal, and may form cribriform structures with small rounded lumens and/or micropapillary tufts lacking fibrovascular cores. More importantly, intraductal carcinoma of the prostate should be distinguished from high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and urothelial carcinoma . Most cases of intraductal carcinoma of the prostate have a Gleason score of 4 + 4 = 8 or higher.

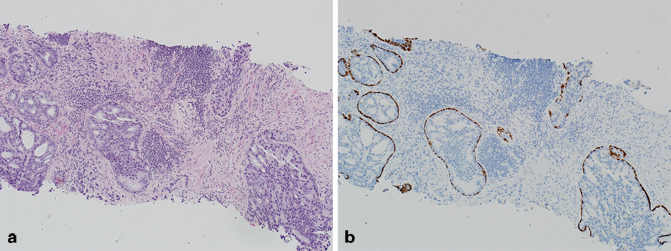

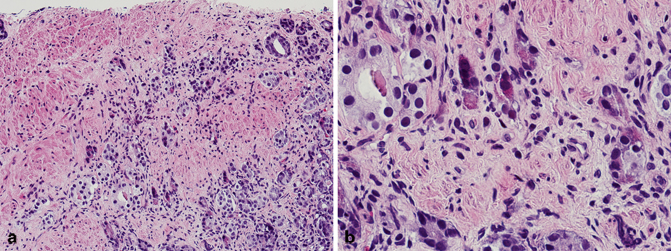

Fig. 5.3

a Needle core biopsy, intraductal carcinoma of the prostate (H & E). b Needle core biopsy, intraductal carcinoma of the prostate (p63/high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (HMWCK))

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

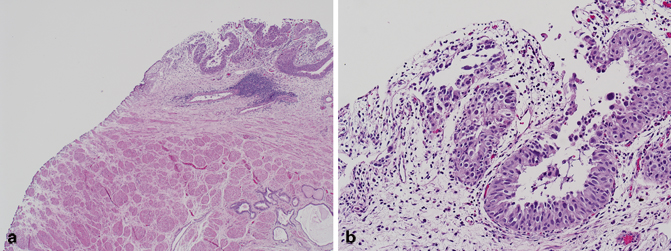

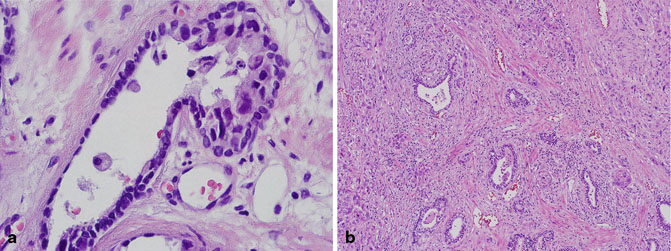

Squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate may occur in a pure form, or may be intimately admixed with prostatic adenocarcinoma (Fig. 5.4). The tumors may arise from the prostatic ducts and acini, but it is important to also realize that these tumors may also arise from the prostatic urethra. It is well established that most cases of squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate occur in the setting of prior radiation therapy and/or androgen deprivation therapy [20−24]. Similar to other variants, squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate is more aggressive than conventional low-grade acinar prostatic adenocarcinoma. Florid squamous metaplasia secondary to prostatic infarcts, inflammation, prior radiation therapy, and/or androgen deprivation therapy, may be a potential mimicker of squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate. The absence of frank malignant features in squamous metaplasia, should exclude the possibility of squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate. Secondary involvement of the prostate by squamous cell carcinoma or urothelial carcinoma with extensive squamous differentiation of bladder origin should also be excluded. This is especially important in needle core biopsies in which the true site of origin of the tumor may not be appreciated.

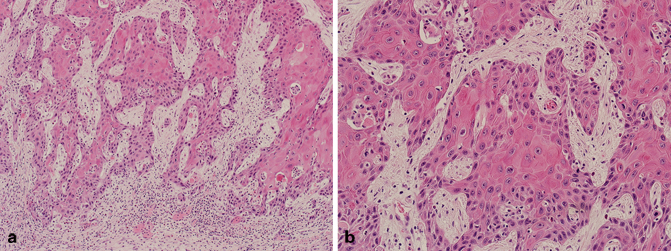

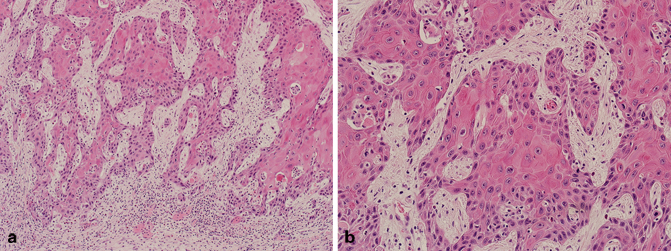

Fig. 5.4

a Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), squamous cell carcinoma (low magnification). b TURP, squamous cell carcinoma (high magnification)

Sarcomatoid Carcinoma

Sarcomatoid carcinoma (carcinosarcoma) is composed of both malignant epithelial (typically adenocarcinoma) and mesenchymal (typically sarcoma) elements (Fig. 5.5) [24−26]. Although there has been some debate regarding the origin of these tumors, both the epithelial and mesenchymal components are thought by most experts to be derived from a single cell of origin [27]. This variant of prostate cancer typically occurs in elderly patients, and may present with an expansile mass that may extend to the transition zone, subsequently resulting in obstructive symptomatology [26]. The sarcomatoid component may demonstrate a spectrum of histologic patterns, ranging from haphazardly arranged spindle cells with or without intimately admixed pleomorphic giant cells and numerous mitotic figures, to more distinct sarcomatous proliferations with heterologous elements, including osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and angiosarcoma [24]. In the largest study to date, the vast majority of men had a prior history of prostatic adenocarcinoma and had been treated with either radiation or hormonal therapy [28]. The authors, however, found no correlation between either the prior grade of conventional prostatic adenocarcinoma, or the time to progression to sarcomatoid carcinoma and patient survival [28]. The current consensus is that the sarcomatoid component of these tumors should be designated as Gleason pattern 5. Primary high-grade prostatic stromal sarcoma (which typically does not have a malignant epithelial component) should be excluded. The prognosis of sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate is poor.

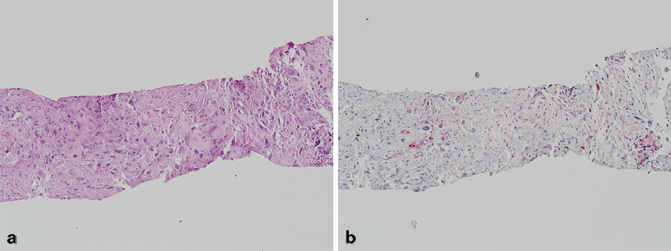

Fig. 5.5

a Needle core biopsy, sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate (H & E). b Needle core biopsy, intraductal carcinoma of the prostate (p63/high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (HMWCK)/P504S)

Prostatic Carcinoid Tumor and Prostatic Adenocarcinoma with Paneth Cell-Like Neuroendocrine Differentiation

True primary carcinoid tumors of the prostate are rare [29−32]. By definition, these tumors should be negative for PSA and PSAP, and must be characterized by typical morphologic and immunohistochemical profile of carcinoid tumor of any other site. What is more prevalent is the so-called prostatic adenocarcinoma with Paneth cell-like neuroendocrine differentiation (Fig. 5.6) [33]. Studies have shown that these tumors have a relatively good prognosis despite the fact that they may be composed predominantly of poorly formed glands or single cells [33]. It is therefore recommended that a Gleason score should not be assigned to these tumors. It is also important to note that high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia may also rarely have Paneth cell-like neuroendocrine differentiation.

Fig. 5.6

a Needle core biopsy, prostatic adenocarcinoma with Paneth cell-like neuroendocrine differentiation (low magnification). b Needle core biopsy, prostatic adenocarcinoma with Paneth cell-like neuroendocrine differentiation (high magnification)

Small Cell Carcinoma

Primary small cell carcinoma of the prostate is a rare and aggressive neoplasm with distinctive clinicopathologic characteristics, including disseminated metastasis [34−40]. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate was first described over three decades ago, and our understanding of the pathobiology of this aggressive tumor has improved over the years [41]. Small cell carcinomas irrespective of the site of origin have very similar morphologic features (Fig. 5.7). The determination of primary origin thus occasional poses a challenge in some cases, especially since immunohistochemical stains such as TTF-1, synaptophysin, chromogranin, and CD56 are positive in most small cell carcinomas irrespective of site of origin. A characteristic feature of pure primary small cell carcinoma of the prostate is the fact that patients typically have low serum PSA levels and a poor response to androgen deprivation therapy. Interestingly, a number of patients have developed small cell carcinoma of the prostate following androgen deprivation therapy for conventional prostatic adenocarcinoma [42−44]. One of the recent advances in our understanding of primary small cell carcinoma of the prostate, is the fact that gene fusions between members of the erythroblast transformation-specific (ETS)-related gene ( ERG) and transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2), have been identified in a significant number of these tumors, compared to small cell carcinoma from other sites [45−49]. This finding confirms the fact that primary small cell carcinoma of the prostate likely represents de-differentiation of conventional prostatic adenocarcinoma. There is also agreement amongst experts that a Gleason score should not be assigned to pure small cell carcinoma of the prostate.

Fig. 5.7

a Needle core biopsy, small cell carcinoma (low magnification). b Radical prostatectomy, small cell carcinoma (high magnification)

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Prostatic adenocarcinoma arises from the secretory cells of the prostatic glands and acini. In contrast, basaloid proliferations of the prostate including basal cell hyperplasia and basal cell carcinoma arise from basal cells of glands typically located in the transition zone, though in some cases peripheral zone involvement may be seen. The distinction between these two entities may occasionally be challenging [50−54]. Basal cell carcinoma is characterized by variably sized basaloid nests with anastomosing areas, eosinophilic luminal lining, and foci of necrosis. The nests typically have an infiltrative growth pattern, and may elicit a desmoplastic stromal response (Fig. 5.8). Cribriforming of the glands with adenoid cystic-like areas may also be seen. Immunohistochemical stains are positive for p63, high–molecular-weight cytokeratin (HMWCK), B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2), CD10, Ki-67 (increased expression), and negative for PSA and PSAP [54, 55]. A Gleason score should not be assigned to basal cell carcinoma.

Fig. 5.8

a Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), basal cell carcinoma with (low magnification). b TURP, basal cell carcinoma with (high magnification)

Urothelial Carcinoma

Primary urothelial carcinoma of the prostate is rare and typically arises from the prostatic urethra or prostatic ducts and acini (Fig. 5.9) [56−58]. Although a number of cases are composed of urothelial carcinoma in situ of the prostatic urethra or colonization of prostatic ducts and acini, a diligent search for possible foci of invasion into the periurethral soft tissue and prostatic stroma should be made. It is also important to note that prostatic stromal invasion due to primary urothelial carcinoma of the prostate and prostatic stromal invasion due to transmural invasion of a bladder primary are staged as pT2 and pT4a, respectively [59].

Fig. 5.9

a Radical prostatectomy, urothelial carcinoma of the prostatic urethra (low magnification). b Radical prostatectomy, urothelial carcinoma of the prostatic urethra (high magnification)

Mucin-Producing Urothelial-Type Adenocarcinoma (Prostatic Urethral Adenocarcinoma)

Rarely, in situ and invasive tumors analogous to mucinous adenocarcinoma of the urinary bladder may arise from the prostatic urethra. These tumors are referred to as mucin-producing urothelial-type adenocarcinoma or prostatic urethral adenocarcinoma (Fig. 5.10) [5, 60−62]. Mean patient age at diagnosis of this aggressive tumor is 72 years (range 58–93 years). In view of the fact that urothelial-type adenocarcinoma of the prostate is identical in its morphology and histogenesis to mucinous adenocarcinoma of the bladder, the latter must be excluded before this diagnosis is rendered. Other tumors that should be considered in the differential diagnosis and excluded include mucinous prostatic adenocarcinoma and mucinous colorectal adenocarcinoma involving the prostate [5, 6, 63]. Immunohistochemical stains are typically positive in the tumor cells for CK7 and negative for PSA, PSAP, b-catenin, and CDX2.

Fig. 5.10

a Radical prostatectomy, mucin-producing urothelial-type adenocarcinoma/prostatic urethral adenocarcinoma (low magnification). b Radical prostatectomy, mucin-producing urothelial-type adenocarcinoma/prostatic urethral adenocarcinoma (high magnification)

Other primary epithelial and epithelial-like tumors involving the prostate include but are not limited to squamous cell carcinoma, Wilms’ tumor, clear cell adenocarcinoma, neuroblastoma, and melanoma.

Secondary Epithelial Tumors

Secondary tumors involving the prostate excluding those from direct extension are rare. Metastasis from other sites to the prostate typically arise from the lung, gastrointestinal tract, skin (melanoma), kidney , testicle, and endocrine organs, with an incidence ranging from 0.1 to 6 % depending on the series [64−66]. In view of the proximity to the prostate, the most common secondary tumor involving the prostate through direct extension is from the urinary bladder . Colorectal tumors including colorectal adenocarcinoma may also occasionally involve the prostate.

Urothelial Carcinoma

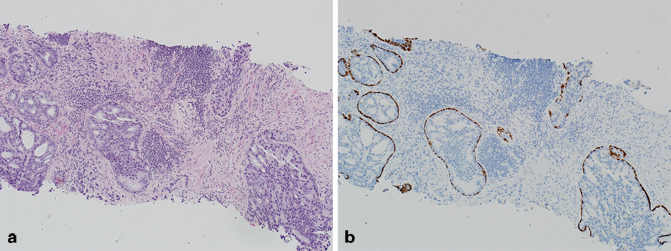

The incidence of prostatic involvement by urothelial carcinoma of the bladder in radical cystoprostatectomy specimens ranges from 12 to 48 % [67, 68]. Prostatic stromal invasion in this setting typically occurs by direct transmural extension of urothelial carcinoma from the bladder primary, and is designated as stage pT4a (Fig. 5.11) [59, 69]. The challenge occurs if the tumor is detected first on needle core biopsy or transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), in the absence of a known history of urothelial carcinoma. Making the distinction between urothelial carcinoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma is critical in view of the different therapeutic options and approaches for these tumors. In cases that are challenging on H & E, readily available immunohistochemical stains (PSA, PSAP, p63, HMWCK, uroplakin and thrombomodulin, GATA3) can aid in the distinction between these two entities in most cases. In the few cases in which the distinction can still not be made with the previous markers, additional immunohistochemical stains (P501S, PSMA, NKX3.1, and pPSA), which are typically positive even in advanced prostatic adenocarcinoma and negative in urothelial carcinoma , are useful [70].

Fig. 5.11

a Radical cystoprostatectomy, urothelial carcinoma with colonization of prostatic ducts. b Radical cystoprostatectomy, urothelial carcinoma with prostatic stromal invasion

Colorectal Adenocarcinoma

Despite the proximity of the colorectum to the prostate, involvement of the prostate from this site in clinical specimens is rare with only very few case reports and series in the literature (Fig. 5.12) [63]. Although most patients present with classic symptoms of colonic cancer, patients may present with obstructive uropathy due to involvement of the prostatic urethra, and may therefore be diagnosed for the first time following TURP [63]. Histologically, the two most common entities that are in the differential diagnosis of colorectal adenocarcinoma invading the prostate are prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the bladder . In addition, the various patterns of infiltrating colorectal adenocarcinoma, including mucinous, enteric, and signet-ring cell type, may also be seen in prostatic adenocarcinoma. Most colonic adenocarcinomas are positive for CDX2, villin, β-catenin, mucins (MUC1 and MUC3), CEA, and B72.3; and all are negative for prostate-specific markers.

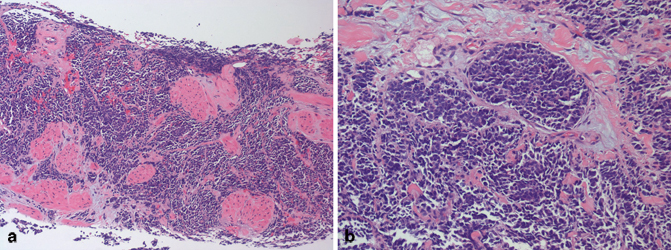

Fig. 5.12

a Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), colorectal adenocarcinoma with necrosis involving the prostate (low magnification). b TURP, colorectal adenocarcinoma with necrosis involving the prostate (high magnification)

Primary Mesenchymal Tumors of the Prostate

Benign or malignant mesenchymal neoplasms of the prostate are rare. Apart from smooth muscle tumors involving the prostate, another group of tumors which arise from the specialized prostatic stroma are also recognized as distinct entities. These tumors have been classified into prostatic stromal tumors of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP) and prostatic stromal sarcoma [71−73].

Stromal Tumors of Uncertain Malignant Potential (STUMP)

These tumors arise from the specialized hormonally responsive stroma of the prostate. There are at least four main histologic patterns of STUMP; hypercellular stroma with scattered atypical/degenerative cells, hypercellular stroma with bland stromal cells, myxoid pattern and “phyllodes”-like pattern, with the first two being the most common (Fig. 5.13). The various histologic patterns of STUMP may be confused with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). However, it should be noted that some cases of STUMP may have the potential to undergo malignant transformation, or may be intimately associated with stromal sarcoma, and thus should be recognized as a distinct entity from BPH. STUMP may be associated with various epithelial proliferations, and it is therefore thought that this may represent epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk [74]. Prostatic adenocarcinoma may also occasionally be identified in cases of STUMP.