Patient Story

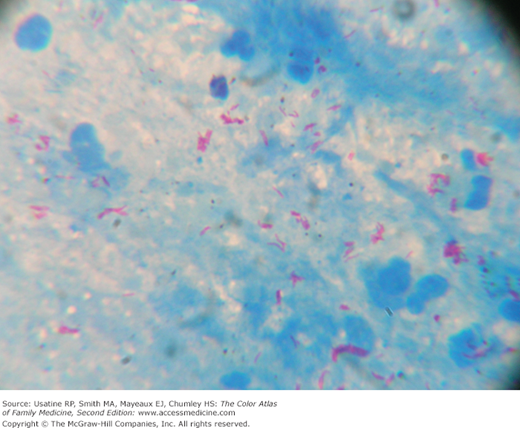

A 20-year-old man from Mexico presents to the emergency room in a South Texas hospital with a persistent cough for 3 weeks, low-grade fever, and night sweats. His chest x-ray shows mediastinal and right hilar lymphadenopathy and right upper lobe consolidation concerning for primary tuberculosis (Figure 54-1). Upon review of the radiograph, the emergency room staff admits the patient to a single room with negative pressure. The patient is placed in respiratory isolation, sputum is sent for acid-fast bacillus (AFB) stain and cultures, and the results show acid-fast bacilli consistent with Mycobacterium spp. (Figure 54-2). While culture results are pending, the patient is started on 4 antituberculosis drugs. Fortunately, the sputum culture result shows pan susceptible Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and his treatment continues with directly observed therapy through the local city health department.

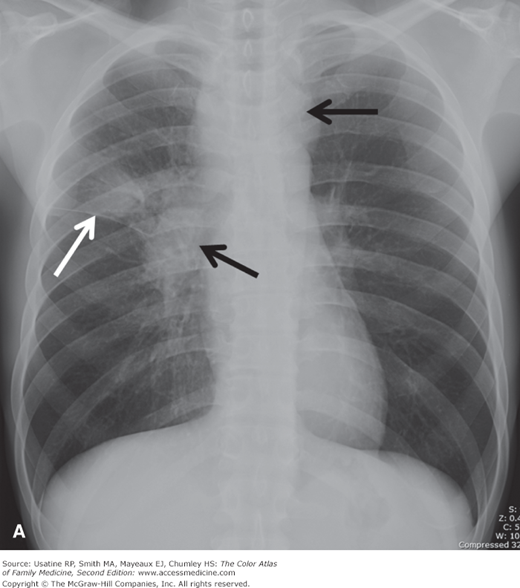

Figure 54-1

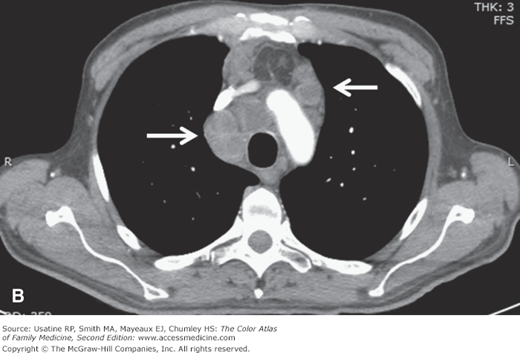

Typical presentation of a primary pulmonary tuberculosis infection in a 20-year-old man. A. Frontal chest radiograph shows mediastinal and right hilar lymphadenopathy (black arrows) and right upper lobe consolidation (white arrow). B. Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates low-density enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes with rim peripheral enhancement consistent with necrotizing lymphadenopathy (arrows). (Courtesy of Carlos Santiago Restrepo, MD.)

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a bacterial infection caused by M. tuberculosis, an obligate intracellular pathogen that is aerobic, acid fast, and nonencapsulated. TB primarily involves the lungs, although other organs are involved in one-third of cases. Improvements in diagnostics, drugs, vaccines, and understanding of biomarkers of disease activity are expected to change future management of this devastating worldwide disease.

Epidemiology

- More than 8 million cases occur annually around the world, with nearly 2 million TB-related deaths1; 95% of TB deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries.

- A total of 11,182 TB cases (3.6 per 100,000 persons) were reported in the United States in 2010. This represents the lowest incidence rate since recording began in 1953.2 An estimated 2 billion people worldwide have latent TB.3

- The multiple-drug resistant (MDR) TB rate in the United States was 1.2% (88 cases) in 2010; a rate that remains relatively stable in the United States.1 MDR TB rates are highest in India, China, the Russian federation, South Africa, and Bangladesh.3

- Based on the 2010 data, 60% of reported U.S. cases of M. tuberculosis occurred in foreign-born individuals (case rate 11 times higher than U.S.-born individuals).1

- There were 547 reported deaths from TB in the United States in 2009 (a 7% decrease from 2008).1

- Prophylactic treatment of those with latent TB (infection without active disease—diagnosed by tuberculin skin test conversion from negative to positive or by an interferon gamma release assay performed on blood) can reduce the risk of active TB by 90% or more.4 SOR A

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Infection is transmitted by aerosolized respiratory droplet nuclei.

- Approximately 10% of those infected develop active TB, usually within 1 to 2 years of exposure; risk factors for the development of active TB are listed below.

- There are 3 host responses to infection—Immediate nonspecific macrophage and likely neutrophil ingestion of those bacilli reaching the alveoli, later tissue-damaging response (delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction), and specific macrophage activating and potentially neutrophil-related response, the latter, if effective, walling off infection into granulomas. Recent evidence suggests that mycobacteria themselves may promote granuloma formation and these granulomas are dynamic, blurring distinctions between latent and active TB.3

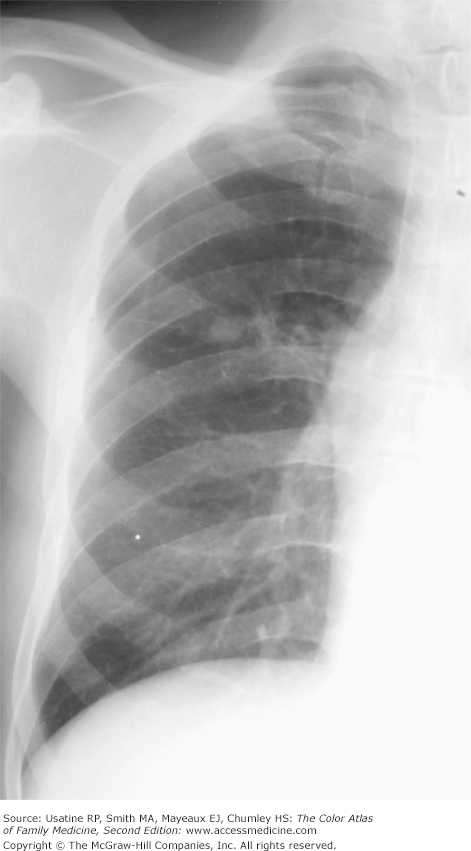

- In areas of high prevalence, TB is often seen in children. The disease process usually localizes to the middle and upper lung zones accompanied by hilar and paratracheal lymphadenopathy (as the tubercle bacilli spread from lung to lymphatic vessels). The primary focus usually heals spontaneously and may disappear entirely or, if encapsulated by fibroblasts and collagen fibers, be visible as a calcified lung nodule (Ghon complex) (Figure 54-3).

Risk Factors

- Minority and foreign-born populations (subject to overcrowding and malnutrition).

- HIV (relative risk [RR] for progression to active TB 100) and other immunocompromised states (e.g., cancer, treatment with tumor necrosis factor antagonists) (RR [progression to active TB] 10). As a result of the high susceptibility of HIV-infected patients, 12% of worldwide TB cases are HIV-associated with sub-Saharan Africa accounting for 4 of every 5 of these cases.3

- Chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus (RR 3) or chronic renal failure/hemodialysis (RR [infection and progression to active TB] 10 to 25 for renal failure).

- Malignancy.

- Genetic susceptibility.

- Bariatric surgery or jejunoileal bypass (RR [progression to active TB] 30 to 60) recipients.

- Injection drug users (RR [progression to active TB] 10 to 30).

- Smoking (RR 2 for progression and infection).

- Personnel who work or live in high-risk settings (e.g., prisons, long-term care facilities, and hospitals).

- Adult women (ratio 2:1 adult man).

- Older age (both infection and progression).

- Children younger than 4 years of age who are exposed to high-risk individuals.

- Recent infection (<1 year) (RR [progression to active TB] 12.9 vs. old infection).

- Fibrotic lung lesions (spontaneously healed) (RR [progression to active TB] 2 to 20).

- Silicosis (RR [infection] 3 and RR [progression to active TB] 30).

- Malnutrition (RR [progression to active TB] 2).

- In a study of hospital personnel, only the percentage of low-income persons within the employee’s residential postal zone was independently associated with conversion (odds ratio [OR] 1.39, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09 to 1.78).5

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of active TB requires a high index of suspicion. In addition, targeted testing for latent TB in vulnerable populations that would benefit from treatment (recent [<5 years] immigrants, immunosuppressed patients, patients with diabetes mellitus and/or chronic renal disease, recent TB or close contact with someone with TB such as household members and healthcare workers) is suggested.6 Manifestations of active TB can be classified as pulmonary or extrapulmonary. TB can affect any organ system.

The disease may be asymptomatic (1 in 4 culture-confirmed cases from active case finding in Asia).3

Pulmonary:

- Early nonspecific signs and symptoms: fever, night sweats, fatigue, anorexia, weight loss.

- Later nonproductive cough (lasting 2 to 3 weeks) or cough with purulent sputum.

- Patients with extensive disease may develop dyspnea or acute respiratory distress syndrome.

- Physical examination findings also nonspecific with crackles or rhonchi.

Extrapulmonary TB, caused by hematogenous spread, occurs in the following order of frequency4:

- Lymph nodes: painless swelling of cervical and supraclavicular nodes (scrofula) (Figure 54-4).

- Pleura: pleural effusion with exudates.

- Genitourinary tract: may cause urethral stricture, kidney damage or infertility (in women, affects the fallopian tubes and endometrium).

- Bones and joints: pain in the spine (Pott disease, Figure 54-5), hips, or knees.

- Other less common sites are meninges, peritoneum, intestines, skin, eye, ear, and pericardium.

- TB of the skin (scrofuloderma) shows ulcerations of the skin (Figures 54-4 and 54-6) in the inguinal or cervical region along with lymphadenopathy.

Positive results on either a tuberculin skin test (TST) or an interferon-γ release assay (IGRA) in the absence of active TB establish a diagnosis of latent TB infection.

- TST with purified protein derivative (PPD) is not useful in diagnosing active TB but is used to detect latent infection in exposed or high-risk individuals. A positive test is 10 mm induration at the inoculation site or 5 mm induration in a patient who is immunocompromised; evaluated in 48 to 72 hours after test placement.

- Two commercially produced IGRAs are licensed for use in the United States and in many other countries: QuantiFERON-TB Gold (QFT-G, Cellestis Limited, Carnegie, Victoria, Australia) and TSPOT.TB (Oxford Immunotec, Inc; Oxford, England) as an aid for diagnosing M. tuberculosis infection.3

- IGRAs detect the release of interferon-γ in fresh heparinized whole blood from sensitized persons when it is incubated with mixtures of synthetic peptides using antigens present in M. tuberculosis. Advantages include no need for a return visit and greater specificity than skin testing. Disadvantages include cost, availability, and lack of supporting data that these tests improve patient outcomes.

- IGRAs have limited accuracy in diagnosing active TB in HIV-infected patients and should not be used alone to rule out or rule in disease.7 In one study of children investigated for TB in 6 U.K. pediatric centers, TST had a sensitivity of 82%, QuantiFERON-TB Gold in tube (QFT-IT) had a sensitivity of 78% and TSPOT.TB of 66%; combining TST and IGRA results increased sensitivity for both tests (ability to rule out TB).8 In practice, IGRA have become standard of care for M. tuberculosis screening in some HIV clinics.

- Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) on sputum specimens are under investigation and are being used to confirm diagnosis in some institutions.3

- Nonspecific findings include mild anemia and leukocytosis.

- Urinalysis may show “sterile” pyuria and hematuria with urinary tract involvement.

- Acid-fast bacilli may be seen on acid-fast staining from sputum or pleural or peritoneal fluid (Figure 54-2). They may also be seen upon staining tissue from fine-needle aspiration or biopsy of lymph nodes or other tissues as above. Sputum processing with bleach or sodium hydroxide and centrifugation and use of fluorescent microscopy is associated with increased sensitivity of smear microscopy.3

- Definitive diagnosis is based on culture of sputum (3 sets of samples collected 8 to 24 hours apart), urine (3 morning specimens—positive in 90% with urinary tract infection), or from tissue or bone biopsy using automated liquid culture systems. M. tuberculosis is slow growing and may take 4 to 8 weeks to identify. Authors of a recent review note that one specimen should be tested with NAAT.9 Once identified, testing for drug sensitivity should be performed.

- Obtaining baseline liver enzymes is recommended for patients older than age 35 years, or for those with a history of liver disease, HIV infection, pregnancy (or within 3 months postdelivery), concomitant hepatotoxic therapy, or regular alcohol use.

- Testing vision, including color vision, is suggested prior to initiating and throughout treatment with ethambutol, which can cause irreversible cumulative toxicity to the optic nerve.

- Biomarkers of disease activity are an area of active investigation; however, a simple, inexpensive point-of-care test is still not available.

- Chest x-ray (CXR) is the diagnostic test of choice and classically shows upper lobe infiltrates with cavitation and/or lymphadenopathy (Figures 54-1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree