55

Trematodes

CHAPTER CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

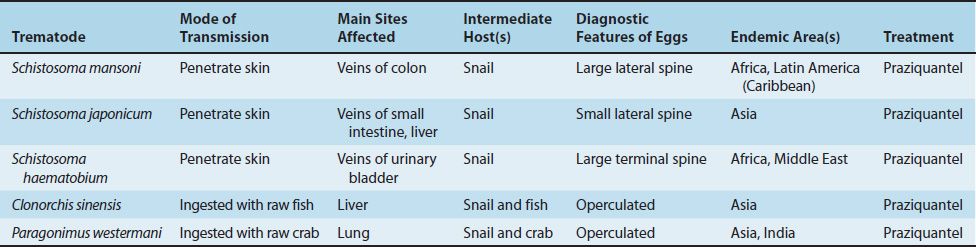

Trematoda (flukes) and Cestoda (tapeworms) are the two large classes of parasites in the phylum Platyhelminthes. The most important trematodes are Schistosoma species (blood flukes), Clonorchis sinensis (liver fluke), and Paragonimus westermani (lung fluke). Schistosomes have by far the greatest impact in terms of the number of people infected, morbidity, and mortality. Features of the medically important trematodes are summarized in Table 55–1, and the medically important stages in the life cycle of these organisms are described in Table 55–2. Three trematodes of lesser importance, Fasciola hepatica, Fasciolopsis buski, and Heterophyes heterophyes, are described at the end of this chapter.

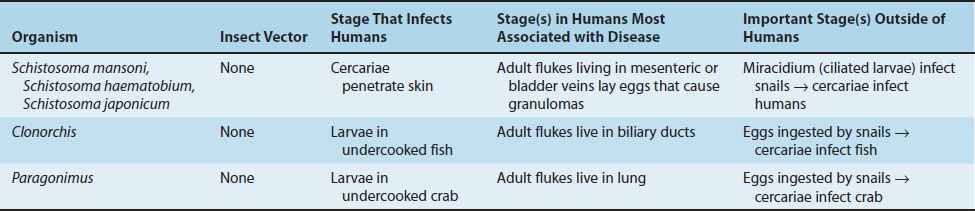

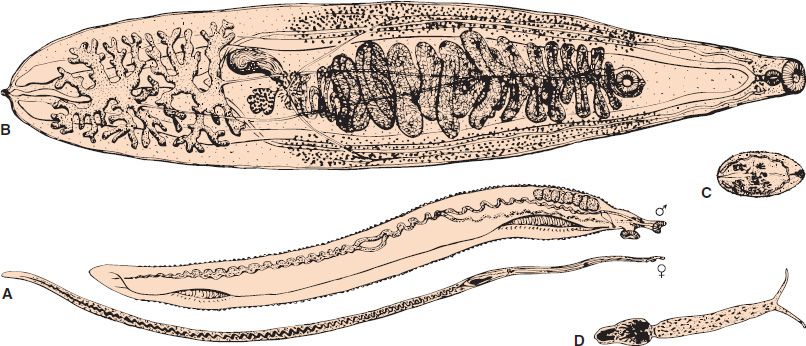

The life cycle of the medically important trematodes involves a sexual cycle in humans (definitive host) and asexual reproduction in freshwater snails (intermediate hosts) (Figure 55–1). Transmission to humans takes place either via penetration of the skin by the free-swimming cercariae of the schistosomes (Figures 55–2D and 55–3) or via ingestion of cysts in undercooked (raw) fish or crabs in Clonorchis and Paragonimus infection, respectively.

FIGURE 55–1 Schistosoma species. Life cycle. Right side of figure describes the stages within the human (blue arrows). Humans are infected at step 2 when free-swimming cercariae penetrate human skin. Cercariae differentiate into adult worms (two sexes) that migrate to the mesenteric veins (Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum) or the venous plexus of the urinary bladder (Schistosoma haematobium). The adult worms lay eggs, which appear in the stool (S. mansoni and S. japonicum) or the urine (S. haematobium). The eggs pass into fresh water, where the miracidia stage infects snails, which produce cercariae. Left side of figure describes the stages in fresh water and in the snail (red arrows). (Provider: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Dr. Alexander J. da Silva and Melanie Moser.)

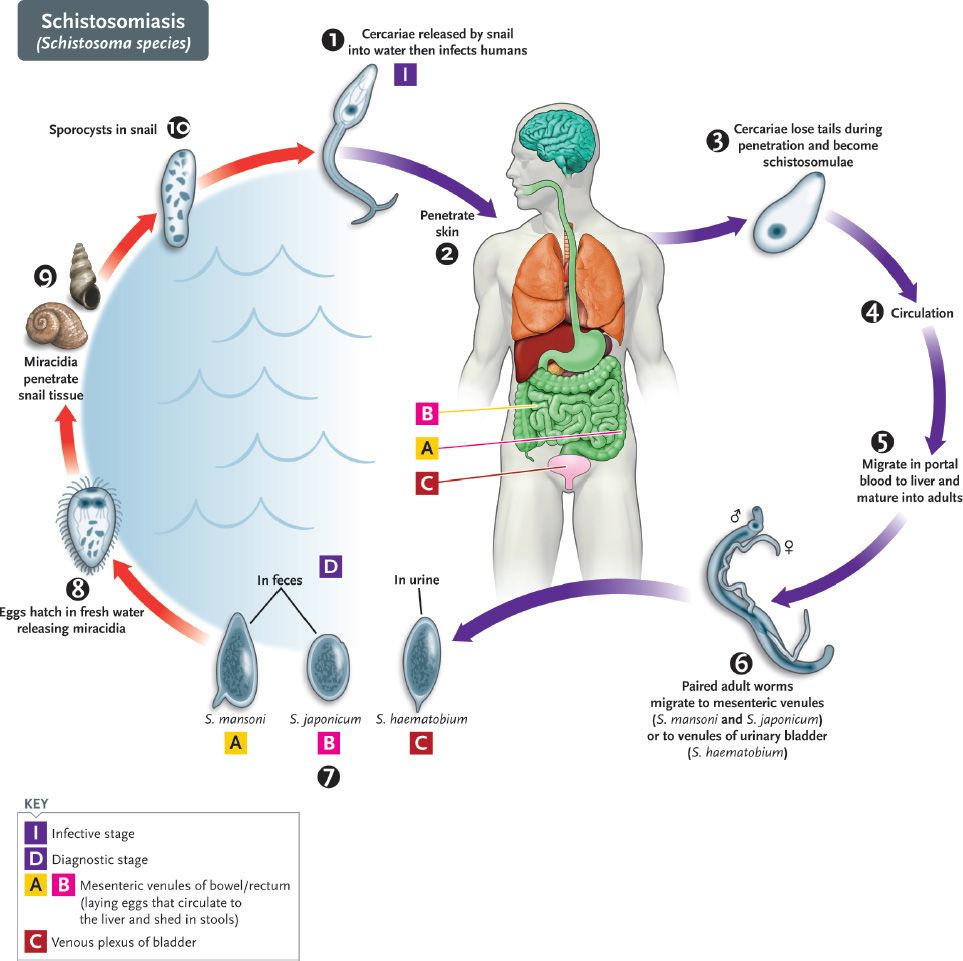

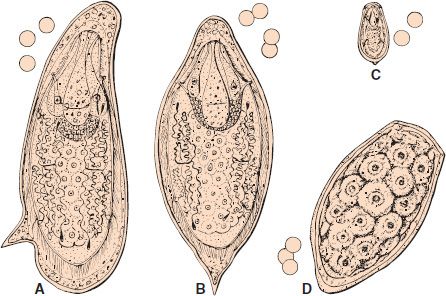

FIGURE 55–2 A: Male and female Schistosoma mansoni adults. The female lives in the male’s schist (shown as a ventral opening) (6×). B: Clonorchis sinensis adult (6×). C: Paragonimus westermani adult (0.6×). D: S. mansoni cercaria (300×).

FIGURE 55–3 Schistosoma—cercaria. Arrow points to a cercaria of Schistosoma. Note the typical forked tail on the left side of the image. (Figure courtesy of Minnesota Department of Health, R.N. Barr Library; Librarians M. Rethlefson and M. Jones; Prof. W.Wiley, Public Health Image Library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Trematodes that cause human disease are not endemic in the United States. However, immigrants from tropical areas, especially Southeast Asia, are frequently infected.

SCHISTOSOMA

Disease

Schistosoma causes schistosomiasis. Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum affect the gastrointestinal tract,1 whereas Schistosoma haematobium affects the urinary tract.

Important Properties

The life cycle of Schistosoma species is shown in Figure 55–1. In contrast to the other trematodes, which are hermaphrodites, adult schistosomes exist as separate sexes but live attached to each other. The female resides in a groove in the male, the gynecophoric canal (“schist”), where he continuously fertilizes her eggs (Figure 55–2A). The three species can be distinguished by the appearance of their eggs in the microscope: S. mansoni eggs have a prominent lateral spine, whereas S. japonicum eggs have a very small lateral spine and S. haematobium eggs have a terminal spine (Figures 55–4A and B, 55–5, and 55–6). S. mansoni and S. japonicum adults live in the mesenteric veins, whereas S. haematobium lives in the veins draining the urinary bladder. Schistosomes are therefore known as blood flukes.

FIGURE 55–4 A: Schistosoma mansoni egg with lateral spine. B: Schistosoma haematobium egg with terminal spine. C: Clonorchis sinensis egg with operculum. D: Paragonimus westermani egg with operculum (300×). (Circles represent red blood cells.)

FIGURE 55–5 Schistosoma mansoni—egg. Long arrow points to an egg of S. mansoni. Short arrow points to its large lateral spine. (Figure courtesy of Public Health Image Library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

FIGURE 55–6 Schistosoma haematobium—egg. Long arrow points to an egg of S. haematobium. Short arrow points to its terminal spine. (Figure courtesy of Public Health Image Library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree