36

CHAPTER OUTLINE

■ SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM IN OLDER ADULTHOOD

■ BROAD-BASED ASSESSMENT OF SUBSTANCE USE PROBLEMS

■ BRIEF INTERVENTION CONTENT AND STEPS

■ FORMAL SUBSTANCE ABUSE TREATMENT IN OLDER ADULTHOOD

The increase in illnesses in later life can lead to higher utilization of health care among older adults (1–4). Many of the medical and psychiatric disorders experienced in aging are influenced by lifestyle choices such as drinking alcohol and use or misuse of medications/drugs. Older adults are more vulnerable to the effects of alcohol and medications and, combined with their increased risk for comorbid diseases, may seek health care for a variety of conditions that are not immediately associated with alcohol or medication use/misuse. These include greater risk for harmful drug interactions, injury, depression, memory problems, liver disease, cardiovascular disease, cognitive changes, and sleep problems (5–7).

Older adults with alcohol problems are a special and vulnerable population who require elder-specific screening and intervention procedures. At-risk drinking and problem drinking are the largest classes of substance use problems seen in older adults.

Illicit drug use and dependence are more common in cohorts born after World War II (8,9). These findings indicate that the “baby boom” cohort, with the leading edge at age 66, may need more intervention and treatment options than those have been available for the current elderly population. With the aging of the baby boom generation, clinicians are likely to see a greater use of alcohol, psychoactive prescription medication misuse, and illicit drug use (10,11).

Recent results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (12) showed that lifetime rates of nonmedical prescription drug use disorders for the oldest age group (65+) were relatively low (<1% with odds ratios of 1) and that younger age groups were most likely to abuse sedatives, tranquilizers, opioids, or amphetamines. Of note is the 45- to 64-year age group who had somewhat higher rates of nonmedical prescription drug abuse than today’s elderly (sedatives: 1.3%, OR = 19.4; tranquilizers: 1.0%, OR = 7.9; opioids: 1.3%, OR = 8.6; amphetamines: 2.1%, OR = 19.0). Illicit drug use and dependence are more common in cohorts born after World War II (8,9).

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM IN OLDER ADULTHOOD

Alcohol

Despite significant advances over the last two decades in the understanding of the aging process, little attention has been paid to the intersection of the fields of gerontology/ geriatrics and alcohol studies. Although studies in this area remain limited, prevalence estimates and typical characteristics of older problem drinkers now are being reported (13–15). Specific treatment and intervention strategies for older adults who are alcohol-dependent or hazardous drinkers are beginning to be disseminated. It can be important to distinguish older adults who have had a history of problems with alcohol (early-onset problems) compared to those who do not develop problems related to alcohol until later in life (late-onset problems) due to stressors that develop with aging (e.g., retirement, loss of income, loss of partner). The majority of older adults experiencing alcohol abuse and/or dependence in later life have had problems with alcohol at various periods earlier in life. However, it is important for clinicians to ask their older patients about alcohol use even if they have no history of problems because problems can arise with stressors in older adulthood (6).

Over a number of years, community surveys have estimated the prevalence of at-risk or problem drinking among older adults to range from 1% to 16% (5,16–18). These rates vary widely depending on the definitions of older adults, at-risk and problem drinking, alcohol abuse/dependence, and the methodology used in obtaining samples. At-risk drinking increases the potential for developing problems and complications. Generally, problem drinking is defined as drinking that has caused some social, emotional, or physical health consequences (see chapter section titled, Alcohol Use Guidelines for Older Adults for specifics). The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH, 2002–2003) found that, for individuals aged 50+, 12.2% were heavy drinkers, 3.2% were binge drinkers (more than four drinks on a drinking occasion), and 1.8% used illicit drugs (12,19). The 2005–2006 NSDUH showed a significant level of binge drinking among those aged 50 to 64 (20). They also found that 19% of men and 13% of women had two or more drinks a day, considered at-risk drinking. The survey also found binge drinking in those over 65, with 14% of men and 3% of women engaging in binge drinking.

Estimates of alcohol problems are even higher among health care–seeking populations, because problem drinkers are more likely to seek medical care (21). Early studies in primary care settings found 10% to 15% of older patients met the criteria for at-risk or problem drinking (22,23). In a large primary care study of 5,065 patients over age 60, Adams et al. (13) found that 15% of the men and 12% of the women sampled regularly drank in excess of the National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA) guidelines (see Alcohol Use Guidelines for Older Adults later in text).

Because patients with a previous history of problems with alcohol or other drugs are at risk for an exacerbation of problems with additional stressors, establishing a history of use can provide important clues for future problems and can provide the opportunity to provide prevention messages and encouragement to individuals who are maintaining abstinence or very low use. Although it is generally assumed that life events such as bereavement and serious illnesses can put the most stress on individuals, any changes in life events (e.g., retirement, change in income) can produce stress that can, in turn, affect alcohol use patterns.

Two studies in nursing homes reported that 29% to 49% of residents had a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence, with 10% to 18% reporting active dependence symptoms in the past year (24,25). In 2002, over 616,000 adults aged 55 and older reported alcohol dependence in the past year: 1.8% of those aged 55 to 59, 1.5% of those aged 60 to 64, and 0.5% of those aged 65 or older (26).

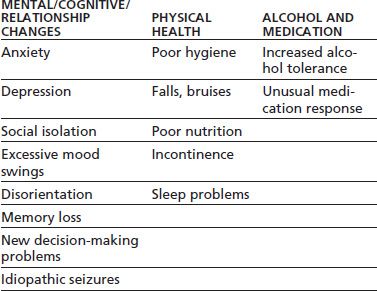

Despite the high prevalence of alcohol problems, most elderly patients with alcohol problems go unidentified by health care personnel. Signs and symptoms of problems related to alcohol use in older adults are shown in Table 36-1. Few elderly patients with alcohol problems seek help in specialized addiction treatment settings. Given the high utilization of general medical services by the elderly, primary care physicians and other health care professionals are essential for identifying those in need of treatment (27).

TABLE 36-1 SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF POTENTIAL ALCOHOL PROBLEMS IN OLDER ADULTS: TIME TO ASK QUESTIONS

Adapted from Barry KL, Oslin D, Blow FC. Alcohol problems in older adults: prevention and management. New York: Springer Publishing, 2001.

Psychoactive Prescription Medication Misuse

Adults aged 65 years and older comprise 13% of the population but account for 36% of all prescription medications used in the United States (28–30). A 2006 study found that 25% of older adults use prescription psychoactive medications that have abuse potential (31). There are over 2 million aggregate serious adverse drug reactions yearly with 100,000 deaths per year. Adverse drug reactions can affect individuals regardless of age, because older adults generally use more prescription drugs that have interaction potential with other drugs and with alcohol, making them a particularly vulnerable group susceptible to adverse drug reactions.

The medications of most concern with older adults are psychoactive prescription medications. A psychoactive medication, psychopharmaceutical, or psychotropic is a chemical substance that crosses the blood–brain barrier and acts primarily upon the central nervous system, where it affects brain function, resulting in changes in perception, pain, mood, consciousness, cognition, and behavior. This includes legal drugs—prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medications—as well as illicit drugs such as marijuana, cocaine, and methamphetamine.

Of greatest concern are the opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines used to treat anxiety and insomnia. These two classes of medications are an important focus because they are frequently prescribed to older adults, have a high dependence and abuse potential, and interact with alcohol, leading to many negative outcomes.

The existing literature on this topic, while scant, indicates that psychoactive medication misuse affects a small but significant minority of the elderly population (32). A survey of social services agencies indicated that medication misuse affects 18% to 41% of the older clients served, depending on the agency (33) and on how “misuse” is defined. Misuse and abuse of prescription drugs by older adults is not typically done to “get high” (34). Although there are individuals who use prescription drugs to get high, many become problematic users unintentionally due to pain, increased anxiety, and inability to sleep (31), and the most abused medications are obtained by prescription.

Most research conducted on substance use and misuse in older adults has focused on drinking and alcohol abuse. The rates of illegal drug abuse in the current elderly cohort are poorly documented but are thought to be very low (6). Simoni-Wastila et al. (31) found that an estimated 11% of older women (age 50+ in their review) misuse prescription drugs and they estimated that nonmedical use of prescription drugs will increase for this age group to 2.7 million by 2020. Being female, social isolation, a history of substance abuse or mental health disorders, and medical exposure to prescription drugs with abuse potential were associated with psychoactive drug misuse/abuse.

Nicotine

Nicotine dependence remains prevalent across age groups. In an analysis of the 2006 National Health Survey, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated the percentages of current smokers by age group (35). Approximately 24% of adults aged 18 to 44 smoke, whereas 10.2% of those aged 65+ are current smokers. Although nicotine dependence is common among older adults and interventions to reduce smoking have tremendous benefits, smoking cessation is reviewed in Chapter 59.

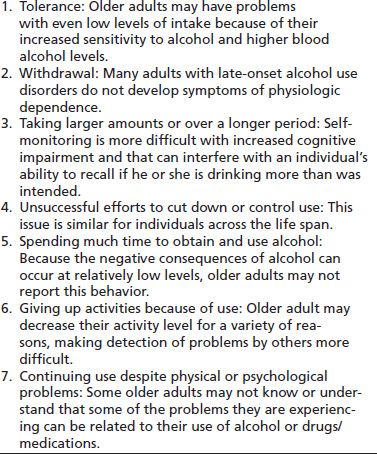

Substance Abuse/Dependence Diagnostic Classification for Older Adults

Clinicians often rely on the criteria published in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Revised (DSM-IV-R), for classifying alcohol-related problems (36). Problems in classifying older adults remain a concern in DSM-5. The criteria may not apply to older adults with substance use problems because older adults may not experience some of the legal, social, or psychological consequences specified in the criteria and often seen in younger adults. “A failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, home, or school” may no longer be as applicable to individuals who are retired and have fewer familial and work obligations (6) (see Table 36-2 for the relationship between DSM criteria for substance abuse/dependence and issues of older adulthood). The criteria related to physical and emotional consequences of alcohol use, however, remain important.

TABLE 36-2 SUBSTANCE ABUSE/DEPENDENCE CRITERIA CONSIDERATIONS IN DIAGNOSING OLDER ADULTS

Modified from Barry KL, Oslin D, Blow FC. Alcohol problems in older adults: prevention and management. New York: Springer Publishing, 2001; Blow FC. Substance abuse among older adults. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment; Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, 1998.

Issues Unique to Older Adults

Older individuals may have unique drinking and medication misuse patterns, substance-related consequences, social issues, and treatment needs (37). Most older adults who are experiencing problems related to their alcohol consumption technically do not meet the DSM criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence (6,38). However, drinking even small amounts of alcohol can increase risks for problems, particularly when combined with the use of some OTC or prescription medications (23,39).

The use of nonjudgmental, motivational approaches can be a key to successfully engage these patients in care. Older adults also present challenges in applying brief intervention strategies for reducing use. Because of stigma, older adults who drink at at-risk levels often find it particularly difficult to acknowledge their own risky drinking. In addition, chronic medical conditions may make it more difficult for clinicians to recognize the role of alcohol, in particular, in decreased functioning and quality of life. These issues present recognition barriers for both clinicians and older adult adults in identifying the need for change. In working with resistant patients who do not recognize a problematic level of alcohol or drug use, clinicians can begin by teaching about changes in metabolism with aging, the interactions between alcohol and specific medications (especially sedatives), the potential for falls, and the relationship between alcohol and some medical problems (e.g., hypertension).

Co-occurring Disorders in Older Adulthood

Psychiatric comorbidities complicate interventions, treatments, and relapse prevention. It is important to note that alcohol and other drugs can affect emotional health long before psychiatric diagnoses are made and early interventions can be the key to maintain emotional and physical health functioning. Studies of older adults with substance use disorders indicate the high rates of co-occurring psychiatric illnesses, ranging from 21% to 66% (40–43). Illnesses, bereavement, job loss, and retirement can all be issues that can worsen depressive responses and alcohol use. Chronic pain, difficulty sleeping, and anxiety are other factors that can increase misuse of psychoactive medications.

Depression and alcohol use are the most commonly cited co-occurring disorders in older adults. For example, nearly half of community-dwelling older adults with a history of alcohol abuse have co-occurring depressive symptoms (42). Approximately 29% of older veterans receiving treatment for alcohol use disorders have a co-occurring psychiatric disorder (44), most commonly an affective disorder (45). Among a population of older adults receiving in-home services, 9.6% had an alcohol abuse problem, and two-thirds of those individuals (6% of the overall sample) had a comorbid psychiatric illness such as depression or dementia (46). Depression and co-occurring risk drinking in older adults are associated with increased suicidality (both suicide ideation and completed suicides) and greater inpatient and outpatient service utilization (47–51). It is important to note that not all suicide attempts require an intervening state of depression—when alcohol is involved, carelessness, despair, disinhibition, and unexpected drug interactions (e.g., alcohol and potent opioid analgesics or sleep medications) can be factors.

Among older adults with a recognized substance abuse disorder attending a substance abuse rehabilitation treatment program, 23% had dementia, and 12% had affective disorders (43). Finally, psychiatric comorbidity was prevalent among older persons (age 65+) hospitalized for prescription drug dependence, with indications that 32% had a mood disorder and 12% had an anxiety disorder (52).

Research has indicated that at-risk and problem drinking can aggravate affective disorders, such as depression, among elders (44,53–55). Even low and moderate levels of drinking among older adults with psychiatric problems can influence treatment outcomes for a variety of psychiatric diagnoses. There is a small body of literature addressing comorbid alcohol abuse/dependence and affective disorders in older adults. Research has shown a strong association between depression and alcohol use disorders across age cohorts; this linkage continues in later life. In a national study of persons aged 65 and older, 13.3% of those with major lifetime depression also met criteria for a lifetime alcohol use disorder, whereas only 4.5% had a lifetime alcohol use disorder without a history of depression (55).

Studies of treatment populations have demonstrated the prevalence of comorbid affective disorders and alcohol abuse among older adults. Blixen et al. (56) found 38% of older adults admitted to a psychiatric hospital had both a substance abuse disorder and another psychiatric disorder, most often depressive symptoms or major depressive disorder. Blow et al. (40) found major depression among 8% to 12% of older alcohol-dependent patients in treatment and dysthymic disorder among 5% to 8% of the same population.

At-risk drinking and problem drinking among the elderly are likely to exacerbate existing depressive disorders (53,57). Associations have been shown between current alcohol consumption and depression scores on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale in persons aged 65 and older (55) and past alcohol consumption and current depressive disorders in older men.

Subsyndromal depression may be aggravated by drinking leading to a major depressive disorder. This is exemplified in grief-associated depressive symptoms or late-life adjustment disorders with depressed mood (53) that may increase to levels indicative of a major depressive disorder. For example, a recently widowed person may be depressed and use alcohol in an attempt to mitigate these feelings.

Comorbid depressive symptoms are not only common in late life but are also an important factor in the course and prognosis of psychiatric disorders. Depressed alcohol-dependent patients have been shown to have a more complicated clinical course of depression with an increased risk of suicide and more social dysfunction than nondepressed alcohol-dependent patients (37,38). Moreover, they have been shown to seek treatment more often. Relapse rates for those who were alcohol dependent, however, did not appear to be influenced by the presence of depression. Alcohol use before late life has also been shown to influence treatment of late-life depression. Studies have found that a prior history of alcohol abuse predicted a more severe and chronic course for depression (58,59).

Alcohol Use Guidelines for Older Adults

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) on older adults recommend that persons, male or female, aged 65 and older consume no more than 1 standard drink/day or 7 standard drinks/week (20,53). In addition, older males should consume no more than four standard drinks on any drinking day. These drinking limit recommendations are consistent with data regarding the relationship between the level of consumption and alcohol-related problems (6,60,61). Drinking guidelines also highlight an important distinction between problem drinking or at-risk drinking and alcohol dependence. A clarification of alcohol problem levels includes the following:

■ At-risk drinking: Use that increases the chances that an individual will develop problems and complications. Persons older than age 65 who drink more than 7 drinks/ week—one per day—are in this category.

■ Problem drinking: Older adults engaging in problem use are drinking at a level that has already resulted in adverse medical, psychological, or social consequences. Potential consequences can include injuries, medication interaction problems, and family problems, among others. Because of aging-related physiologic changes, some older adults who drink even small amounts of alcohol can experience alcohol-related problems.

■ Abuse/dependence: The terms alcohol abuse and dependence are defined in the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria.

Screening and Detection of Alcohol and Psychoactive Medication Misuse in Older Adults

The overall model and approach to the process of screening and intervening with individuals who may have at-risk or problem use of alcohol is called SBIRT—Screening, Brief Interventions, and Referral to Treatment. Clinicians should screen for alcohol use (frequency and quantity), drinking consequences, use of psychoactive prescription medications, levels of use, and alcohol/medication interactions. Screening can be done as part of routine mental and physical health care and updated annually, before the older adult begins taking any new medications or in response to problems that may be alcohol or medication related. The SAMHSA CSAT TIP #26 expert panel (23) recommended screening all adults aged 60+ on a yearly basis and when there are changes that warrant additional screening (e.g., major life events—retirement, loss of partner/spouse, chances in health). Clinicians can obtain more accurate histories by asking questions about the recent past, embedding the alcohol use questions in the context of other health behaviors (i.e., exercise, weight, smoking, alcohol use) and asking straightforward questions in a nonjudgmental manner.

The “brown bag approach”—where the clinician asks the patient to bring in all medications, OTC preparations, and herbs in a brown paper bag to the next clinical visit—is one potential means of getting more reliable information. Many states allow physicians or pharmacists to query a state database of controlled substance prescriptions without a patient’s consent. This can reveal multiple prescribers for controlled substances, such as opioid analgesics. Used together, these two strategies allow the provider to determine what the patient is taking and what, if any, interaction effect these medications, OTCs, and herbs may have with each other and with alcohol. OTC use often remains unevaluated in clinical settings, and the use of some OTC preparations (particularly anticholinergic agents) can be problematic in combinations with alcohol or prescriptions.

Screening questions can be asked by verbal interview, by paper-and-pencil questionnaire, or by computerized questionnaire. All three methods are reliable and valid (62). Any positive responses can lead to further questions. To successfully incorporate alcohol, psychoactive prescription medication, and other drug screening into clinical practice with older adults, one needs simple and consistent routines used along with other screening procedures already in place (63).

Before asking any screening questions, the following conditions are helpful: The interviewer needs to be empathetic and nonthreatening; the purpose of the questions should be clearly related to health status, the information must be confidential; and the questions need to be easy to understand. In some settings (such as waiting rooms), screening instruments are administered as self-report questionnaires with instructions for patients to discuss the meaning of the results with their health care providers. However, paper instruments need larger typefaces to accommodate patients with visual problems.

The following interview guidelines can be used. For patients requiring emergency treatment or for those who are temporarily impaired, it is best to wait until their condition has stabilized. However, assessing the current condition of the patient can be done at any point; signs of alcohol or drug intoxication should be noted. Patients who have alcohol on their breath or appear intoxicated may give incomplete responses, so consideration should be given to following up the initial interview when the level of intoxication is not a factor. If the alcohol questions are embedded in a longer health interview, a transitional statement is needed to move into the alcohol-related questions. The best way to introduce alcohol questions is to give the patient a general idea of the content of the questions, their purpose, and the need for accurate answers (62). This statement should be followed by a description of the types of alcoholic beverages typically consumed. If necessary, clinicians may include a description of beverages that may not be considered (e.g., cider, low alcohol beer). Determinations of consumption are based on “standard drinks.” A standard drink is a 12-ounce bottle of beer, a 5-ounce glass of wine, or 1.5 ounces (a shot) of liquor (e.g., vodka, gin, whiskey).

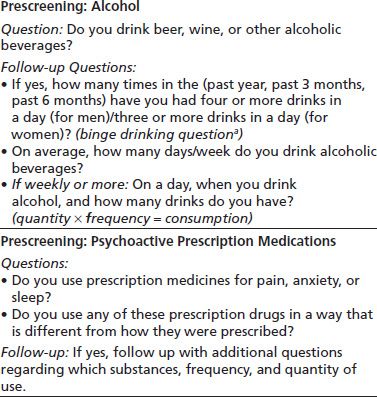

Screening Process

The first step in screening can be called prescreening. This is simply asking a few questions to rule out the majority of individuals who do not need more systematic screening to determine the extent of the problem (64). Prescreening generally identifies at-risk and harmful substance use, while more extensive screening measures the severity of the substance use, problems and consequences associated with use, factors that may be contributing to substance abuse, and other characteristics of the problem. The prescreening and screening process should help determine if a patient’s substance use is appropriate for brief intervention or warrants a different approach. Because prescreening questionnaires can be quickly and easily administered as part of standard health screening in many clinical settings, they are an efficient method to determine who needs additional screening questions and who does not. For example, the questions in Tables 36-3 and 36-4 make an easy-to-use prescreening instrument. The prescreening questions for psychoactive prescription medications simply ascertain if the older adult is using any of the targeted medications.

TABLE 36-3 PRESCREENING QUESTIONS ADAPTED FROM THE AUDIT

aAn older adult who reports either binge drinking or drinking above NIAAA guidelines can complete follow-up screening questionnaires.

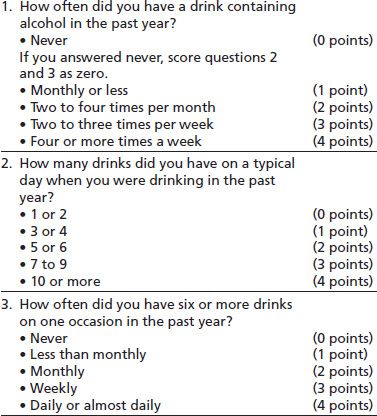

TABLE 36-4 AUDIT-C ALCOHOL SCREENING

The AUDIT-C is scored on a scale of 0 to 12 (scores of 0 reflect no alcohol use). A score of 3 or more in older adults is considered positive and suggests the need for further evaluation. Generally, the higher the AUDIT-C score, the more likely it is that the patient’s drinking is affecting his/her health and safety.

(From Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson S, et al. Effectiveness of the derived Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) in screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the U.S. general population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005;29(5):844–854.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree