27

CHAPTER OUTLINE

The ASAM Criteria for the treatment of addictive, substance-related, and co-occurring conditions have its roots in the mid-1980s. The developers of two sets of placement criteria that were gaining some national attention at the time joined with the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) to lead and advocate for one national set of criteria that would unify the addiction treatment field. The National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers (NAATP) joined with ASAM to create the criteria by integrating and revising the Cleveland Criteria of the Northern Ohio Chemical Dependency Treatment Directors Association (NOCDTDA) (1) with the NAATP Criteria (2). Both NOCDTDA and NAATP agreed to allow a third set of national criteria to supersede their organizations’ documents, despite considerable investments of time, effort, and financial resources in developing the separate criteria.

ASAM was entrusted to lead this advocacy and in 1991 published the Patient Placement Criteria for the Treatment of Psychoactive Substance Use Disorders (3). Multidisciplinary groups of addiction treatment specialists, involving counselors, psychologists, social workers, and physicians, worked to develop one national set of consensus criteria to promote a common language and placement guidelines for the treatment of addiction disorders. The ASAM Criteria were designed to help clinicians, payers, and regulators use and fund levels of care in a rational and individualized treatment manner. This moved the addiction treatment field away from fixed programs to an assessment-based, clinically driven, outcome-oriented continuum of care.

The continuing development and refinement of the criteria represent a shift from

1. One-dimensional to multidimensional assessment—from treatment based on diagnosis to treatment that is holistic addressing multiple needs

2. Program-driven to clinically and outcome-driven treatment—from placement in a program often with fixed lengths of stay to person-centered, individualized treatment responsive to specific needs and progress and outcome in treatment

3. Fixed length of service to a variable length of service, based on patient needs and outcomes

4. A limited number of discrete levels of care to a broad and flexible continuum of care

The ASAM Criteria describe six assessment dimensions that are used to differentiate patient needs for services across levels of care. A second edition was developed in 1996, ASAM PPC-2 (4), and in 2001, a revision of PPC-2 was published, ASAM PPC-2R (5). A further revision, The ASAM Criteria, (6), published in October 2013, contains information to expand application of the criteria to special populations of older adults, parents with children, people in safety-sensitive occupations, and criminal justice populations. There are also sections on tobacco use disorder and gambling disorder, which have never been included in the ASAM Criteria before. What continues is a goal to promote assessment and treatment that is individualized, person centered, and outcome driven rather than program driven and placement centered (7–9).

There are separate criteria sets for adults and adolescents. A survey of all 50 US state authorities conducted for the National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors found that 43 states (84%) required the use of standard Patient Placement Criteria (10). Among the states that require Patient Placement Criteria, approximately two-thirds require providers to use the ASAM Criteria, and this percentage is growing. The U.S. Department of Defense has endorsed the ASAM Criteria, and a national survey of the Veterans Healthcare Administration addiction program leaders reported that 48% were very familiar with the ASAM Criteria (11). A wide variety of public and private managed care companies and payers use the ASAM Criteria for decisions on authorizing addiction treatment.

SELECTING APPROPRIATE SERVICES

Evolving Approaches to Treatment Matching

The process of matching patients to treatment services has evolved through at least four approaches, each with a fundamentally different philosophy (12,13).

Complication-driven treatment gives only cursory attention to the diagnosis of a substance use disorder. In this approach, rather than actively treating the primary alcohol or other drug disorder that is causing the patient’s symptoms, only the secondary complications or sequelae are addressed. The gastritis or bleeding esophageal varices are controlled, the depression is medicated, fractures are splinted or pinned, but care for the addiction disorder is superficial or nonexistent.

In contrast, diagnosis, program-driven treatment recognizes the primacy of the substance use disorder, but the diagnosis alone drives the treatment plan, level of care, and length of stay (LOS), rather than the specific assessed needs of the patient. For example, even before a comprehensive assessment is completed, patients are assigned to a fixed LOS outpatient or residential program. In such program-driven services, patients who ask “How long do I have to be in the program?” are told a specific number of sessions, weeks or months. Often, the focus is on compliance with program rules and graduation from the program. For some patients, services in program-driven treatment is in response to a mandated referral, policy guidelines, or available funding or benefit structures rather than placement based on a multidimensional assessment, which defines the next approach.

In individualized, assessment-driven treatment, service priorities are identified in the context of the patient’s severity of illness and level of function. Treatment services are matched to the patient’s needs over a continuum of care (14). Ongoing assessment of progress and treatment response influences further service recommendations and length of treatment. This continuous quality improvement cycle—assessment, treatment matching, level of care placement, and progress evaluation through multidimensional assessment—represents an approach to care that much of the addiction treatment field still struggles to fully implement (13).

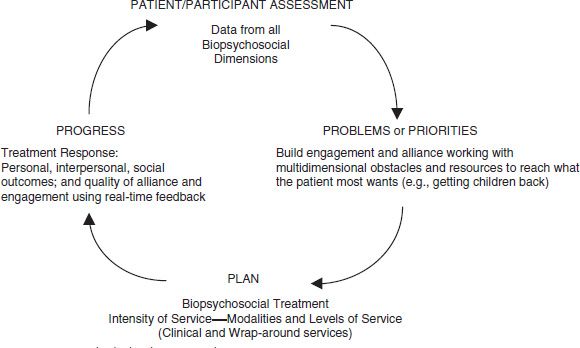

Outcome-driven treatment, the most recent approach, adds the element of measurement of outcomes in real time, so that progress and treatment response is more explicit and influential. The focus on “during treatment” feedback on both outcomes and patient engagement and therapeutic alliance allows real-time modification of the treatment plan. Here, decisions about which problems are prioritized and what changes are made in strategies and level of care are informed by tracking the most salient outcomes and measures of alliance and patient engagement (15) (Fig. 27-1).

FIGURE 27-1 Individualized, outcome-driven treatment.

Uses of Placement Criteria

Placement criteria are irrelevant to the first two approaches to patient placement (complication-driven and program-driven treatment). In the latter two approaches, the ASAM Criteria play an integral role by providing a multidimensional assessment structure, initially to generate a service plan that leads to appropriate placement and then a formal treatment plan that meets the patient’s assessed needs and improves the prospects for a positive outcome once in treatment. The ASAM Criteria also provide a nomenclature and guidelines to describe an expanded set of treatment options and to promote the use of a wider continuum of services. The ASAM Criteria thus are intended to increase access to care, enhance the efficient use of limited resources, and improve outcomes through individualized, assessment-driven treatment and the flexible use of a broad continuum of care.

Increasingly, however, treatment must be driven not only by the assessment but more importantly by the outcome of treatment measured in real time. No single treatment is appropriate for all individuals at all times (16). Therefore, matching treatment settings, interventions, and services to each individual’s particular problems and needs is critical to his or her ultimate success in returning to productive functioning in the family, workplace, and society. Measurement during treatment that tracks real-time outcomes and the quality of the patient’s engagement and therapeutic alliance allows for modification of the strategies and level of care, depending on patient progress or lack thereof (17,18).

The Concept of “Unbundling”

At present, most addiction treatment services are “bundled,” meaning that a number of different services are packaged together and paid for as a unit. However, there has been recognition for some time that clinical services can be and often are provided separately from recovery environment supports (19). Unbundling is a practice that allows any type of clinical service (such as psychiatric consultation) to be delivered in any setting (such as a residential program) or, for example, partial hospitalization combined with supportive living instead of residential care for those patients who are not in imminent danger. With unbundling, the type and intensity of treatment are based on the patient’s needs and not on limitations imposed by the treatment setting. The unbundling concept thus is designed to maximize individualized care, to reduce costs, and to encourage the delivery of necessary treatment in any clinically feasible setting.

A transition to unbundled treatment would require systems change in state program licensure and reimbursement. In terms of treatment, there would no longer be “programs” but rather a constellation of services to meet the needs of each patient. The systems currently in use for program licensure or accreditation, billing, reimbursement, and funding would not support unbundled treatment. However, the ASAM Criteria encourage exploration of unbundling by suggesting ways to match risk and severity of needs with specific services and intensity of treatment.

To assist clinicians and programs to advance this approach, the ASAM Criteria include the Matrix for Matching Severity and Level of Function with Type and Intensity of Services, which provides benchmarks to determine the level of risk in each dimension on a scale of 0 to 4, the needed services, and the relevant intensity and level of care. The Matrix format has been applied to Dimensions 1 and 5, acute intoxication and/or withdrawal potential and relapse, continued use, or continued problem potential, respectively, to guide pharmacotherapies for alcohol use disorders (20).

UNDERSTANDING THE ASAM CRITERIA

Four features characterize the ASAM Criteria: (a) comprehensive, individualized treatment planning, (b) ready access to services, (c) attention to multiple treatment needs, and (d) ongoing reassessment and modification of the plan.

Functionally, the criteria are used to match services, interventions, and treatment settings to each individual’s particular problems and (often-changing) treatment needs as well as his or her strengths, skills, and resources. The ASAM Criteria advocate for individualized, assessment-driven treatment and the flexible use of services across a broad continuum of care.

The criteria also advocate for a system in which treatment is readily available, because patients are lost when the treatment they need is not immediately available and readily accessible. By expanding the criteria to incorporate more use of outpatient care, especially for those in early stages of readiness to change; expanding to five levels of withdrawal management; and encouraging flexible lengths of stay, the ASAM Criteria are designed to assist in reducing waiting lists for residential treatment and thus improve access to care.

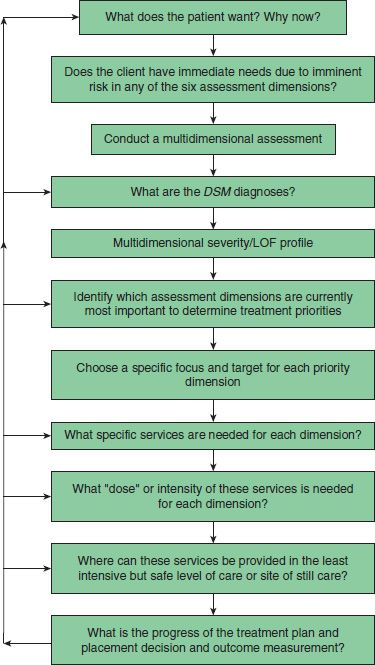

The criteria are based on a philosophy that effective treatment attends to multiple needs of each individual, not just his or her alcohol or other drug use. To be effective, treatment must address any associated medical, psychological, social, vocational, legal, and recovery environment problems. Through its six assessment dimensions, the ASAM Criteria underscore the importance of multidimensional assessment and treatment. To engage the patient in a collaborative therapeutic alliance, the assessment is in the service of what the patient wants; for example, “Get my children back.” It serves to identify obstacles and resources and liabilities and strengths within each of the assessment dimensions (Fig. 27-2).

FIGURE 27-2 Decision tree to match assessment and treatment/placement assignment. DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, American Psychiatric Association; LOF, level of function.

Objectivity

The criteria are as objective, measurable, and quantifiable as possible. Certain aspects of the criteria require subjective interpretation. In this regard, the assessment and treatment of addictive and substance-related disorders are no different from biomedical or psychiatric conditions in which diagnosis or assessment and treatment are a mix of objectively measured criteria and experientially based professional judgments.

Principles Guiding the Criteria

Several important principles have guided development of the ASAM Criteria.

Goals of Treatment

The goals of intervention and treatment (including safe and comfortable withdrawal management, motivational enhancement to accept the need for recovery, the attainment of skills to achieve abstinence) determine the methods, intensity, frequency, and types of services provided. The health care professional’s decision to prescribe a type of service and subsequent discharge of a patient from a level of care are based on how that treatment and its duration will help resolve dysfunction and positively alter the prognosis for the patient’s long-term outcome.

Thus, in addiction treatment, the treatment may extend beyond simple resolution of observable signs and symptoms to the achievement of overall healthier functioning, the difference between abstinence alone and recovery. The patient demonstrates a response to treatment through new insights, attitudes, and behaviors. Addiction treatment programs have as their goal not simply stabilizing the patient’s condition but altering the course of the patient’s disease.

Individualized Treatment Plan

Treatment should be tailored to the needs of the individual and guided by an individualized treatment plan that is developed in collaboration with the patient. Such a plan should be based on the patient’s goals for treatment and a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment of the patient and, when possible, a comprehensive evaluation of the family as well.

The plan should list problems prioritized by obstacles to treatment and risks and to be arranged according to severity (such as obstacles to recovery, knowledge or skill deficits, dysfunction, or loss), strengths (such as peer refusal skills, a positive social support system, and a strong connection to a source of spiritual support), goals (a statement to guide realistic, achievable, short-term resolution of problems or attainment of positive outcomes), objectives, methods or strategies (what the patient will do, the treatment services to be provided, the site of those services, the staff responsible for delivering treatment), and a timetable for follow-through with the treatment plan that promotes accountability.

The plan should be written to facilitate measurement of progress. As with other disease processes, length of service should be linked directly to the patient’s response to treatment (e.g., attainment of the treatment goals and degree of resolution of the identified clinical problems) rather than a predetermined time frame based on the length of the treatment program or available reimbursement.

Choice of Treatment Levels

Referral to a specific level of care must be based on a careful assessment of the patient. The goal that underlies the criteria is the placement of the patient in the most appropriate level of care. For both clinical and financial reasons, the preferred level of care is the least intensive level that meets treatment objectives, while providing safety and security for the patient. Moreover, while the levels of care are presented as discrete levels, in reality, they represent benchmarks or points along a continuum of treatment services that could be used in a variety of ways, depending on a patient’s needs and response. A patient could begin at a more intensive level and move to a more or less intensive level of care, depending on his or her individual needs and progress in treatment. For patients who have been previously treated and have relapsed, the choice of the current level of care should be based on an assessment of the patient’s history and current functioning, not automatic placement in a more intensive level of care. Such placement by policy assumes that relapse after treatment indicates that the previous level of care was of insufficient intensity. In fact, poorly matched services may have been the problem, for example, recovery and relapse prevention services for a patient at an early stage of change who needs “discovery” motivational enhancement services.

Continuum of Care

In order to provide the most clinically appropriate and cost-effective treatment system, a continuum of care must be available. Such a continuum may be offered by a single provider or multiple providers. For the continuum to work most effectively, it is best distinguished by three characteristics: (a) seamless transfer between levels of care, (b) philosophical congruence among the various providers of care, and (c) timely arrival of the patient’s clinical record at the next provider. It is most helpful if providers envision admitting the patient into the continuum through their program rather than admitting the patient to their program.

Many providers of treatment services offer only one of the many levels of care described. In such situations, movement between levels might mean referring the patient out of the provider’s own network of care. While lack of reimbursement for some levels of care or lack of availability of other levels of care may render this impossible at present, the goal of these criteria is to stimulate the development of efficient and effective services with attendant funding or reimbursement that can be made available to all patients.

Progress through the Levels of Care

As a patient moves through treatment in any level of care, his or her progress in all six dimensions should be continually assessed. Such multidimensional assessment ensures comprehensive treatment. In the process of patient assessment, certain problems and priorities are identified as justifying admission to a particular level of care. The resolution of those problems and priorities determines when a patient can be transferred to a different level of care or discharged from treatment. The appearance of new problems may require services that can be effectively provided at the same level of care or that require a more or less intensive level of care.

Each time the patient’s response to treatment is assessed including when a decision is reached to transfer the patient to another level of care or different type of treatment or for maintenance care, new priorities for recovery are identified. The intensity of the strategies incorporated in the treatment plan helps to determine the most efficient and effective level of care that can safely provide the care articulated in the individualized treatment plan. Patients may, however, worsen or fail to improve in a given level of care or with a given type of program. When this happens, changes in the level of care or program should be based on a reassessment of the treatment plan, with modifications to achieve a better therapeutic response.

Should a patient drink or use drugs during treatment, the immediate response should be to revise the treatment plan rather than automatically change the level of care or administratively discharge the patient. Additionally, some benefit managers require that a patient be “motivated for sobriety” as a requirement for admission to a program. Given the characteristic signs of ambivalence and lack of readiness to change of addiction disorders, the only requirement should be that the patient is willing to enter treatment. Clinicians then facilitate the patient’s self-change process along the stages of change.

Length of Stay

The LOS or service is determined by the patient’s progress toward achieving his or her treatment plan goals and objectives. Fixed LOS or program-driven treatment is not individualized and does not respond to the particular problems of a given patient. While fixed LOS programs are more convenient and predictable for the provider, they may be less effective for individuals (16).

Clinical Versus Reimbursement Considerations

The ASAM Criteria describe a wide range of levels and types of care. Not all of these services are available in all locations, nor do all payers cover them. Clinicians who make placement decisions are expected to supplement the criteria with their own clinical judgment, their knowledge of the patient, and their knowledge of the available resources. The ASAM Criteria are not intended as a reimbursement guideline, but rather as a clinical guideline for making the most appropriate placement recommendation for an individual patient with a specific set of symptoms and behaviors. If the criteria only covered the levels of care commonly reimbursable by private insurance carriers, they would not address many of the resources of the public sector and, thus, would tacitly endorse limitations on a complete continuum of care.

Treatment Failure

Two incorrect assumptions are associated with the concept of “treatment failure.” The first is that the disorder is acute rather than chronic, so that the only criterion for success is total and complete cure and elimination of the problem. Such expectations are recognized as inappropriate in the treatment of other chronic disorders, such as diabetes, asthma, or hypertension. No one expects that simply because a patient has been treated on one occasion for asthma, there will never be another episode. The same recognition of chronicity should be applied to the treatment of addiction disorders, for which appropriate criteria would involve reductions in the intensity or severity of symptoms, the duration of symptoms, and the frequency of symptoms.

The second assumption is that responsibility for treatment “failure” always rests with the patient (as in, “the patient was not ready”). However, poor treatment outcomes also may be related to a provider’s failure to provide services tailored to the patient’s needs.

Finally, there is a concern that some benefit managers require that a patient “fail” at one level of care as a prerequisite for approving admission to a more intensive level of care (e.g., “failure” in outpatient treatment as a prerequisite for admission to inpatient treatment). In fact, such a requirement is no more rational than treating every patient in an inpatient program or using a fixed LOS for all. Such a strategy potentially puts the patient at risk because it delays care at a more appropriate level of treatment, and potentially increases health care costs if restricting the appropriate level of treatment allows the addiction disorder to progress.

The ASAM Criteria and State Licensure or Certification

The ASAM Criteria contain descriptions of treatment programs at each level of care, including the setting, staffing, support systems, therapies, assessments, documentation, and treatment plan reviews typically found at that level. This information should be useful to providers who are preparing to serve a particular group of patients, as well as to clinicians who are making placement decisions. Nevertheless, the descriptions are not requirements and are not intended to replace or supersede the relevant statutes, licensure, or certification requirements of any state.

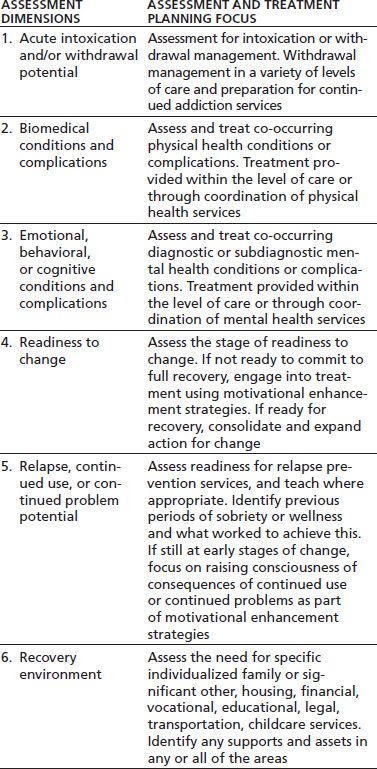

The ASAM Criteria identify six assessment areas (dimensions) as the most important in formulating an individualized treatment plan and in making subsequent patient placement decisions. Table 27-1 outlines the six dimensions and the assessment and treatment planning focus of each dimension.

TABLE 27-1 ASAM CRITERIA ASSESSMENT DIMENSIONS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree