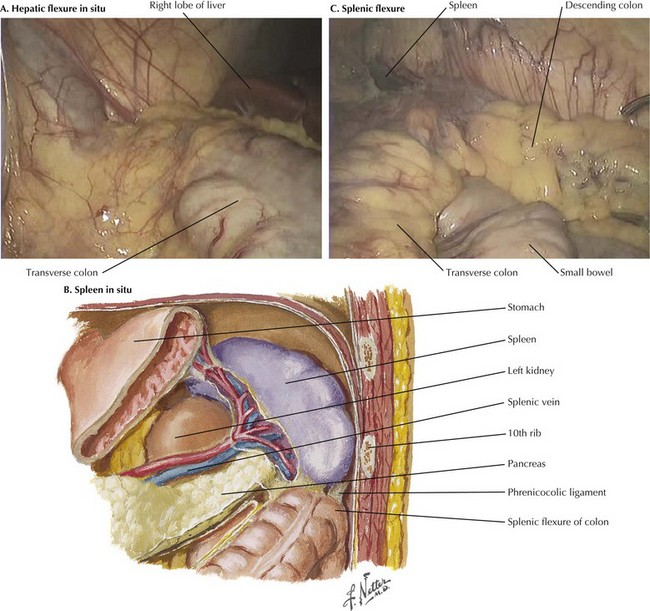

Chapter 23 1. Mobilization of hepatic flexure 2. Mobilization of splenic flexure 3. Dissection of greater omentum off transverse colon, or resection of the omentum 4. Division of middle colic artery and vein 5. Proximal division of the colon 6. Distal division of the colon The intraoperative photograph demonstrates the hepatic flexure in situ (Fig, 23-1, A). The liver is cephalad and the right kidney is posterior. The ascending colon is mobilized from its lateral attachments at the white line of Toldt. As the ascending colon is mobilized medially, the dissection is complete when the duodenum is identified and preserved posteriorly with the retroperitoneum. Aggressive traction near the end of the mobilization may cause avulsion injury to the middle colic vein, which results in difficult-to-control hemorrhage. The splenic (or left) flexure of the colon is the bend in the bowel where the distal transverse colon transitions to the descending colon. To mobilize the splenic flexure, the avascular lateral attachments of the descending colon to the retroperitoneum must be divided along the white line of Toldt. The splenocolic (lienocolic) ligament is the superior extension of this and forms connective bands connecting the apex of the splenic flexure to the inferior aspect of the splenic capsule. The anatomic relations of the splenic flexure in situ are shown in Figure 23-1, B and C.

Transverse Colectomy

Surgical Principles

Anatomy for Transverse Colectomy

Splenic Flexure

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine