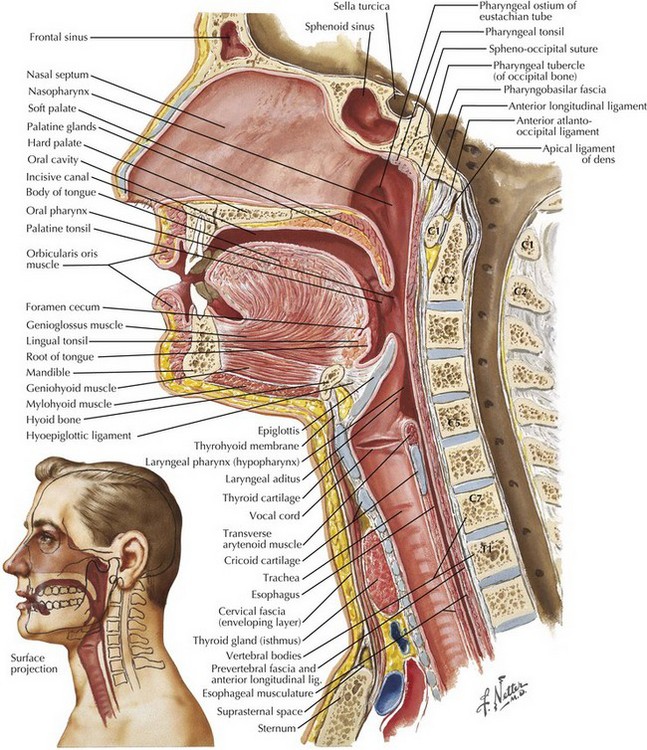

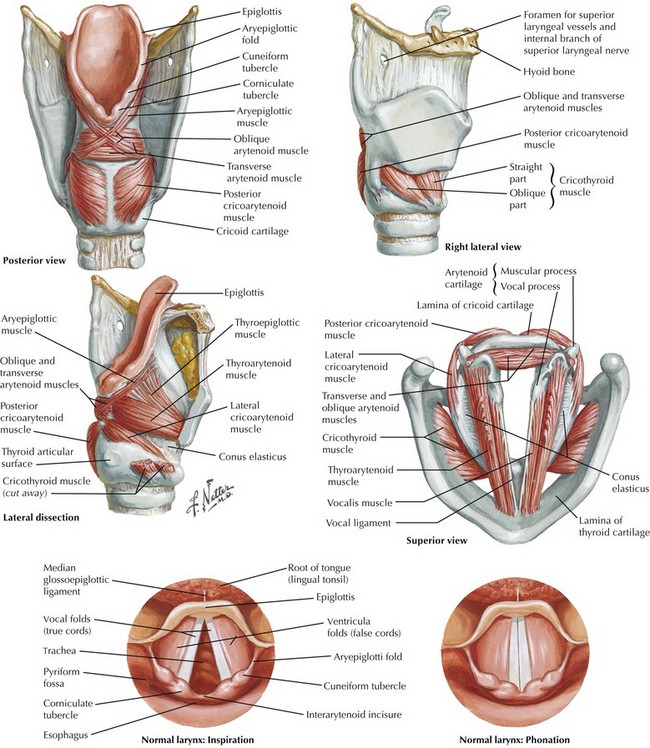

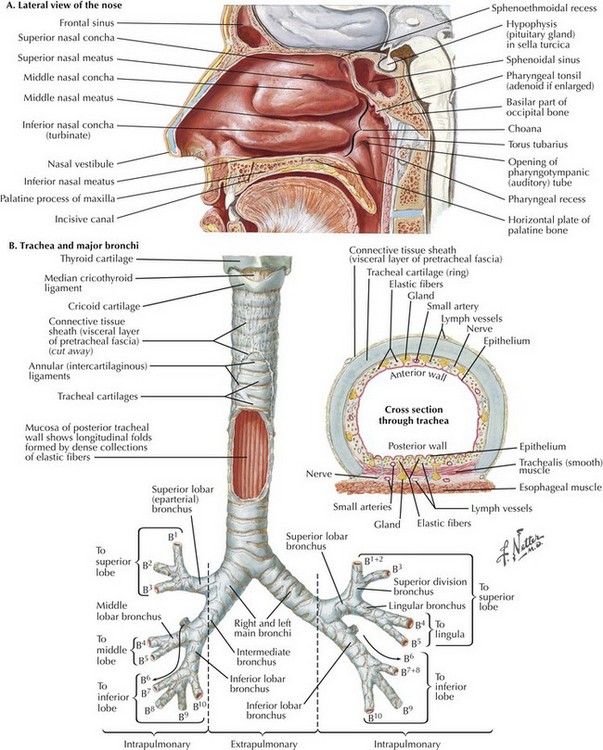

Chapter 45 The upper airway consists of the nose, mouth, pharynx, and larynx. There are three pharyngeal segments: (1) nasopharynx, posterior to the soft palate; (2) oropharynx, posterior to the tongue from the tip of the uvula to the tip of the epiglottis; and (3) laryngopharynx, posterior to the epiglottis (Fig. 45-1). The pharyngeal segments are collapsible because the anterior and lateral walls lack bony support. The larynx serves as the connecting structure between the upper and lower airways (Fig. 45-2). The adult larynx extends from the 4th to the 6th cervical vertebra, and it is composed of nine cartilages, with six paired and three single. The three single cartilages include the thyroid, cricoid, and epiglottis. The paired arytenoid cartilages secure the vocal cords to the larynx. The endolarynx is constructed of two pairs of folds that form the supraglottis and glottis. Note the location of the superior laryngeal nerve (important for nerve block anesthesia) adjacent to the hyoid bone (Fig. 45-2). Motor innervation of the laryngeal muscles is through the superior laryngeal nerve (cricothyroid muscle) and recurrent laryngeal nerve (remainder of laryngeal muscles). Stimulation of the supraglottic region, especially where the piriform recesses blend with the hypopharynx, can result in laryngospasm with complete glottic closure. Nasotracheal intubation is an alternative approach to orotracheal intubation. The two nasal fossae extend from the nostrils to the nasopharynx. The nasal fossae are divided by the midline cartilaginous septum and medial portions of the lateral cartilages (Fig. 45-3, A). The nasal fossa is bounded laterally by inferior, middle, and superior turbinate bones. The mucosa covering the middle turbinate is highly vascular, receiving its blood supply from the anterior ethmoid artery, and also contains a large plexus of veins. The middle turbinate is susceptible to avulsion by trauma and is associated with massive epistaxis. The paranasal sinuses (sphenoid, ethmoid, maxillary, and frontal) open into the lateral wall of the nose. The inferior turbinate usually limits the size of the nasotracheal tube. The lower airway consists of the trachea, bronchus, bronchioles, respiratory bronchioles, and alveoli. The adult trachea, which begins at the cricoid cartilage opposite the 6th cervical vertebra, contains 16 to 20 cartilaginous rings. The posterior part of the trachea is devoid of cartilage (Fig. 45-3, B). Pressure over the cricoid cartilage (Sellick maneuver) is often applied during rapid-sequence induction and intubation (RSI) to minimize the risk of aspiration in unfasted (full stomach), anesthetized, and paralyzed patients before intubation. However, cricoid pressure may distort airway anatomy, making intubation more difficult.

Tracheal Intubation and Endoscopic Anatomy

Airway Anatomy

Upper Airway

Larynx

Nose and Nasopharynx

Lower Airway

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine