Fig. 5.1

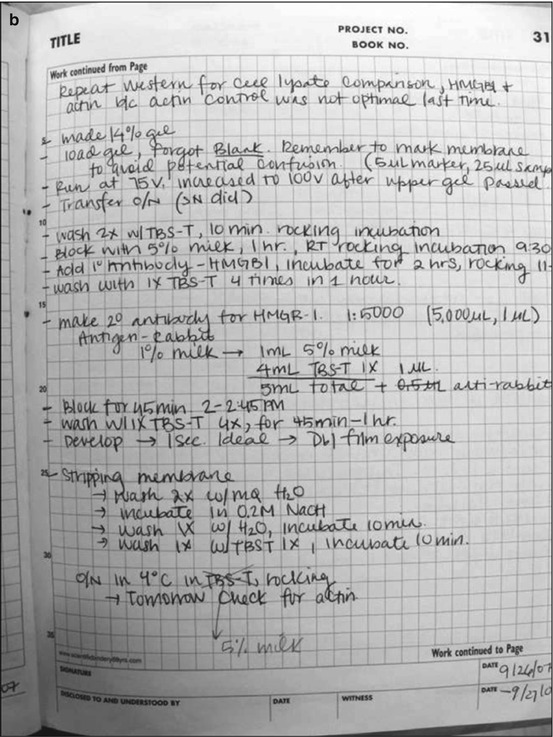

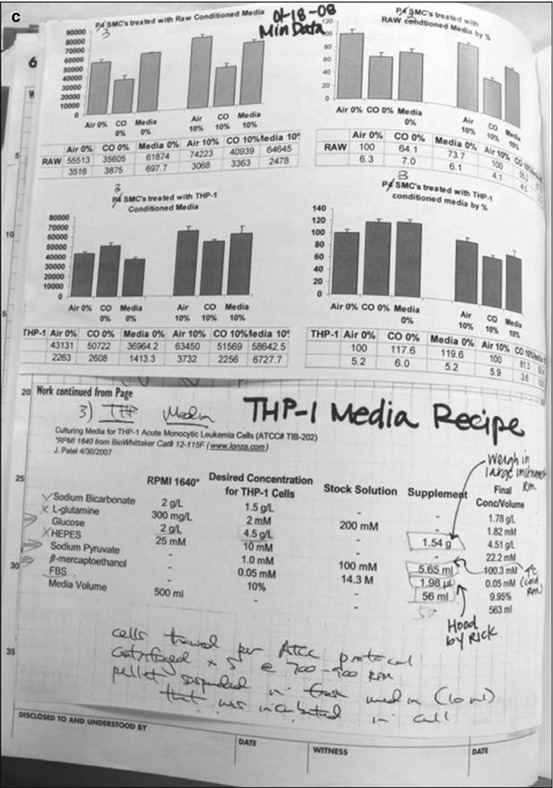

(a) This notebook lacks experimental detail and the date is missing the year. (b) In contrast, this notebook described experimental detail, including deviations from protocol. An error is shown but is easily readable. (c) Data is neatly taped into the notebook including the buffer recipe and details of how it was made

Over the course of the twentieth century, self-recording instrumentation as well as imaging technology has led to major advances in science but has complicated the methods of traditional data storage due to a massive increase in data volume [1]. Examples of this include genomic analysis with gene arrays and proteomic studies that yield very large data sets. Similarly, complex histologic and microscopy techniques produce images and videos that are poorly represented in static photographs. In the past, experiments and their results have been recorded in a bound laboratory notebook. However, the contemporary research record now may include a number of complex data sets and large series of images that simply cannot be translated into a paper format for a notebook. Statistics, findings, and conclusions should also be documented and stored but is often found in an electronic format in proximity to the statistical package used to generate the information. The inclusion of all these different forms of documentation creates a laboratory notebook that is essentially “fragmented” [2] in which a combination of paper records, electronic files spread over a number of different computers in different locations, manila folders replete with printouts or spreadsheets, CDs, and storage devices containing images and videos comprises the “notebook.” The challenge is to create a system in which these fragmented sets of data can be cataloged for easy reference and incorporated into a cohesive, durable, and secure record of experimentation.

Maintenance of the Canonical Laboratory “Notebook”

An organized and detail-oriented approach to data maintenance has many advantages. Organization allows for easy identification of past and present experiments and depicts the results in a manner that can be easily understood and interpreted by others involved in the research. It also allows access to technical aspects of experimentation that promote reproducibility and attest to the integrity of the research. Lack of this information does make it difficult to understand the experiments in the future (Fig. 5.1). Traditionally, bound laboratory notebooks with serially numbered pages have been used to store experimental information and data in a longitudinal fashion. The information should be recorded in permanent ink and should be written neatly in English. The notebook should contain a table of contents at the beginning to allow for easy identification of particular experiments. Each experiment should have a date, title, the investigator and coinvestigator names, hypothesis or clearly stated purpose for the experiment, and methods used. It is important to record the protocol that was used, as well as any technical details that were either included or omitted (intentionally or otherwise). Oftentimes, results are evaluated months or even years after the actual conduct of the experiments, and these notes are particularly helpful in recalling the details of each experiment. Deviations from protocol or difficulties encountered during the conduct of the experiment should be recorded and may offer insight into the accuracy and reliability of the data when analysis is being performed.

In addition to referencing the protocol and detailing the methodology, the reagents should be explicitly described. This may include recording the manufacturer of the reagent, noting lot number, describing the cell line, and documenting the source of antibody. Reagents obtained from other investigators should be cataloged for proper acknowledgement on publication. Additionally, buffer recipes should either be recorded or referenced. Any aberrant conditions in the laboratory should also be documented to help understand unexpected results in the future. Whenever possible, laboratory notebooks should be backed up and protected from damage. Some bound notebooks have carbon copies that allow for a backup paper record, but many paper notebooks are not easily duplicated because of the inclusion of photos and radiographs and other inserted documents. When data is recorded, pages should not be skipped except for in the table of contents. Errors should be corrected with a single line through the material and should be initialed and dated as is the expectation in any other legal documents.

Loose-leaf notebooks have also been used as a primary or supplemental notebook. The advantage of these notebooks is the ability to neatly insert documents that correspond with each experiment such as the outcomes or serial measurements of a long-term experiment. Unfortunately, this same benefit is one of the potential disadvantages of these types of notebooks. The ability to insert or remove pages from this notebook, accidentally or intentionally, may raise concerns for possible tampering that may lead to questions about the integrity of the information within. These types of notebooks are more difficult to defend in a setting of allegations of research misconduct [3]. If they are to be used as a primary notebook, it is prudent to place sheets within sheet protectors and reinforce the holes so that papers are less likely to be pulled out. As in a bound notebook, there should be a table of contents in the beginning, and each experiment should be dated and entered in chronologic order.

When possible, raw data should be stored in the notebook next to the recordings of the experimental protocol. This has often meant taping or gluing a printout or gel image into the notebook. However, many types of data cannot be easily affixed to a notebook such as slides or large numbers of images stored in a computer file. Additionally, in vivo work may generate multiple sets of diverse data that can be difficult to refer to at a later date. In this scenario, our method is to number animals serially and keep a record of each animal number, the intervention(s) performed, the date the interventions were performed, and the date of sacrifice. Observations regarding adverse events, animal behavior, unexpected illness and treatments, and premature euthanasia should also be recorded. This catalog of animals can be kept within the main laboratory notebook but may be better maintained in a separate notebook dedicated to animal information. The animal is then referred to by its number in any experiment using its tissues or blood, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), Western blot, or tissue slide. A slide and image library is also kept separately from the laboratory notebook to facilitate the cataloging process. The location of these data is then clearly indexed in the primary laboratory notebook for reference, simplifying the ability to find the associated results at any time.

For industry and federally regulated laboratories, recorded experiments require signatures by the researcher and a witness. The witness is typically personnel who is not related to the project but has the ability to understand the work that is presented. The witness attests to the authenticity of the research performed which is extremely important should legal defense of research integrity become necessary. Additionally, authenticity of the data is important in patent disputes. In the USA, patent law favors a first-to-invent model as opposed to a first-to-file model. In other words, if there is documentation that shows earlier conceptual and experimental discovery of an invention, it can be used to override a patent application filed for the same invention at a later date. Thus, authenticated and properly dated research records may help resolve disputes as to the ownership of an invention [3]. In contrast, the lack of authenticity can render the laboratory notebook to hearsay and prevent a researcher from claiming rights to an invention [3]. From a practical standpoint, obtaining a witness for each day of experimentation is impractical in the academic setting. However, a more manageable way to handle the task is to set aside time biweekly or monthly to have a designated witness review and sign the notebook [3].

When a notebook is complete, it should be cataloged and stored in a secure location. Ideally, the notebook should be stored for a designated number of years. These notebooks are the property of the laboratory and the institution and are not to be removed by trainees upon completion of their time in the laboratory. This includes all other forms of data storage including tissue banks, image libraries, and electronic data files. This process often is a significant barrier for trainees who have completed their training but wish to continue to work on data interpretation and manuscript preparation from a distance. For this purpose, copies of the notebook and of the other forms of data may be created but the volume of information to be copied may be prohibitive.

Archiving of Scientific Data

Granting agencies are currently making an effort to encourage data archiving to promote sharing of raw data among the scientific community. As per recent funding guidelines from the National Science Foundation, “Proposals submitted or due on or after January 18, 2011, must include a supplementary document of no more than two pages labeled “Data Management Plan.” This supplementary document should describe how the proposal will conform to NSF policy on the dissemination and sharing of research results.” Additionally, many high impact journals require that raw data sets be made accessible to the scientific community, usually in a web-based format. Funding agencies as well as academic institutions require maintenance of data archives for a certain amount of time after publication of the research. The federal government requires that research records be stored for a minimum of 7 years after final publication of the results. For research involving clinical data, these requirements may be longer. It is encouraged that the original data be stored whenever possible. This allows for protection in the case of patent application or litigation. In the unfortunate circumstance in which research integrity has been questioned, records should be kept at least until the matter has been resolved, which may take longer than the 7-year federal requirement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree